33411 SP RES FM 00I-0Viii.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

80 Years of Spanish Cinema Fall, 2013 Tuesday and Thursday, 9:00-10:20Am, Salomon 004

Brown University Department of Hispanic Studies HISP 1290J. Spain on Screen: 80 Years of Spanish Cinema Fall, 2013 Tuesday and Thursday, 9:00-10:20am, Salomon 004 Prof. Sarah Thomas 84 Prospect Street, #301 [email protected] Tel.: (401) 863-2915 Office hours: Thursdays, 11am-1pm Course description: Spain’s is one of the most dynamic and at the same time overlooked of European cinemas. In recent years, Spain has become more internationally visible on screen, especially thanks to filmmakers like Guillermo del Toro, Pedro Almodóvar, and Juan Antonio Bayona. But where does Spanish cinema come from? What themes arise time and again over the course of decades? And what – if anything – can Spain’s cinema tell us about the nation? Does cinema reflect a culture or serve to shape it? This course traces major historical and thematic developments in Spanish cinema from silent films of the 1930s to globalized commercial cinema of the 21st century. Focusing on issues such as landscape, history, memory, violence, sexuality, gender, and the politics of representation, this course will give students a solid training in film analysis and also provide a wide-ranging introduction to Spanish culture. By the end of the semester, students will have gained the skills to write and speak critically about film (in Spanish!), as well as a deeper understanding and appreciation of Spain’s culture, history, and cinema. Prerequisite: HISP 0730, 0740, or equivalent. Films, all written work and many readings are in Spanish. This is a writing-designated course (WRIT) so students should be prepared to craft essays through multiple drafts in workshops with their peers and consultation with the professor. -

Seville Film

SEVILLE IS CINEMA Seville is a city for recording films. Seville has been and continues to be the setting for many national and international television productions and series. We are very pleased to show you the tourist interest places of that have been the setting for these films, as well as information regarding them. How many times have you seen the Plaza de España in “Lawrence of Arabia” or in “Star Wars: Episode II”, and the Casa de Pilatos in “1492: Conquest of Paradise”? Come and visit these prominent landmarks in situ! The Real Alcázar The Real Alcázar is a monumental complex that date back to the Early Middle Ages, constituting the most important civil building in Seville. The surrounding walls, which can be admired from the Plaza del Triunfo, date from the early 10th century. The Patio del Yeso (Courtyard of the Plaster) belongs to the Almohad period between 1147 and 1237. Its ornamentation inspired later Nasrid architecture, but it was the Christian constructions that gave the complex its current appearance. The Gothic Palace, built during the reign of Alfonso X, has been modified due to the work carried out in the 16th century by the Lisbon earthquake of 1755. The most outstanding features in its rooms are the tiled plinths, the work of Cristóbal Augusta between 1577 and 1583, the set of 18th century tapestries depicting the Conquest of Tunis and the reproduction of the Virgin de La Antigua. The Courtroom, built in the middle of the 14th century during the reign of Alfonso XI, is the first example of the Mudejar style in this area, representing a perfect combination of the Islamic and Christian styles. -

Introduction

Introduction 1 Iciar Bollaín (left) rehearsing Mataharis Iciar Bollaín (Madrid, 1967), actress, scriptwriter, director and producer, is one of the most striking figures currently working in the Spanish cinema, and the first Spanish woman filmmaker to make the Oscars shortlist (2010). She has performed in key films directed by, among others, Víctor Erice, José Luis Borau, Felipe Vega and Ken Loach. Starting out as assistant director and coscriptwriter, she has Santaolalla_Bollain.indd 1 04/04/2012 15:38 2 The cinema of Iciar Bollaín gone on to make four short films and five feature films to date, all but one scripted or coscripted by her. She is also one of the founding members of Producciones La Iguana S. L., a film production company in existence since 1991. Her work raises questions about authorship, female agency and the mediation in film of social issues. It also highlights the tensions between creative and industrial priori ties in the cinema, and national and transnational allegiances, while prompting reflection on the contemporary relevance of cinéma engagé. Bollaín’s contribution to Spanish cinema has been acknowledged both by filmgoers and the industry. Te doy mis ojos (Take My Eyes, 2003) is one of a handful of Spanish films seen by over one million spectators, and was the first film made by a woman ever to receive a Best Film Goya Award (Spanish Goyaequivalent) from the Academia de las Artes y las Ciencias Cinematográficas de España (Spanish Film Academy).1 Recognition has also come through her election to the Executive Committee of the College of Directors and Scriptwriters of the SGAE (Sociedad General de Autores y Editores) in July 2007, and to the VicePresidency of the Spanish Film Academy in June 2009.2 The varied range of Bollaín’s contribution to Spanish cinema, and the extent to which she is directly involved in key roles associated with filmmaking, inevitably lead to speculation on the extent to which she may be regarded as an auteur. -

2617 Hon. Tom Latham

February 3, 2009 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS, Vol. 155, Pt. 2 2617 A member of the Committee with responsi- succeeded by another outstanding scholar of has proved to be a dynamic partner in the bility for writing education legislation, I Spanish culture, Professor Jo Labanyi. I NYU Center for European and Mediterranean took part in writing all the laws enacted here must also salute the Director of the Studies and a close partner of our King Juan during those years, 1959 to 1981, during the King Juan Carlos Center office in Madrid, Carlos I of Spain Center. Administrations of six Presidents—three Re- John Healey, who has known Spain for many For example, the Catalan Center, orga- publicans: Eisenhower, Nixon and Ford; and years. nized two years ago, has sponsored the fol- three Democrats: Kennedy, Johnson and Another distinguished leader who has lec- lowing events: Carter—laws to assist schools, colleges and tured at our King Juan Carlos I of Spain Cen- ‘‘A Mediterranean Mirror,’’ an exhibition universities; students who attend them; the ter is a longtime friend, someone well known of books on Catalan law, an opening at- arts and the humanities; libraries and muse- to all of you and with whom I met only tended by President Ernest Benach of the ums; and measures to help children, the el- weeks ago in New York City, the distin- Parliament of Catalonia, and Director of the derly, the disabled. guished former Mayor of Barcelona and Institut Ramo´ n Llull, Josep Bargallo´ . You will not be surprised that as a member President of the Generalitat, Pasqual The Catalan Center has also sponsored a of the Democratic Party in my country and, Maragall i Mira. -

National Gallery of Art Winter 09 Film Program

NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART WINTER 09 FILM PROGRAM 4th Street and Constitution Avenue NW, Washington, DC Mailing address 2000B South Club Drive, Landover, MD 20785 BARCELONA MASTERS: JOSÉ LUIS TEUVO TULIO: THE REBEL SET: GUERÍN NORTHERN FILM AND THE AND PERE IN THE REALM TONES BEAT LEGACY PORTABELLA OF OSHIMA and the City, In the City of Sylvia and the City, Helsinki), calendar page page four Helsinki), (National Audiovisual Archive, page three page two page one cover Of Time and the City The Way You Wanted Me Wanted You The Way The Sign of the Cross The Sign of the Cross WINTER09 Of Time and the City A Town of Love and Hope A Town Pere Portabella (Helena Gomà, Barcelona), Pere details from Song of the Scarlet Flower (Strand Releasing) (Strand Releasing) (Photofest/Paramount) (National Audiovisual Archive, Helsinki), (National Audiovisual Archive, (Photofest) In the City of Sylvia (National Audiovisual Archive, (National Audiovisual Archive, Song of the Scarlet Flower (José Luis Guerín) Of Time Les Lutins du Court-Métrage: New Shorts from France Friday February 13 at 1:00 Film Events Five new examples from France illustrate the beauty and versatility of the short- film form: 200,000 Fantômes (Jean-Gabriel Périot, 2007, 10 minutes); La dernière journée (Olivier Bourbeillon, 2007, 12 minutes); Mic Jean-Louis (Kathy Sebbah, The Sign of the Cross 2007, 26 minutes); Pina Colada (Alice Winocour, 2008, 15 minutes); and L’Enfant Introduction by Martin Winkler borne (Pascal Mieszala, 2007, 15 minutes). Saturday January 3 at 2:30 Ciné-Concert: Show Life British playwright Wilson Barrett’s Victorian melodrama was the source for Stephen Horne on piano Cecil B. -

Cine Educación

LA ACADEMIA DE LAS ARTES Y LAS CIENCIAS CINEMATOGRÁFICAS DE ESPAÑA desea encauzar un interés social que ya era patente tanto en la profesión audiovisual como en el mundo educativo que, en común o por separado, vienen trabajando desde hace tiempo para que el cine adquiera en las aulas la relevancia que merece como patrimonio cultural indiscutible en una sociedad inmersa en el lenguaje audiovisual. EDUCACIÓN Con esta finalidad, la Academia Y ha impulsado el proyecto “Cine DOCUMENTO MARCO y Educación”, en el que han colaborado numerosas personas del para el proyecto pedagógico impulsado sector audiovisual y del pedagógico, por la Academia de las Artes y las quienes han elaborado este libro Ciencias Cinematográficas de España CINE para promover la implantación de planes de alfabetización audiovisual en el sistema educativo no universitario. El Documento Marco que ahora Y presentamos, se compone de CINE tres partes principales: la primera, de carácter expositivo y teórico; la segunda, con el enunciado de iniciativas prácticas y los posibles itinerarios para realizarlas, y una EDUCACIÓN tercera, también fundamental, con cinco Anexos que entendemos de gran utilidad para alcanzar los objetivos pretendidos. y CINEEDUCACIÓN Coordinación Fernando Lara, Mercedes Ruiz y Marta Tarín Han participado en la realización de este libro Agustín García Matilla, Ángel Gonzalvo, Araceli Gozalo, Begoña Soto, Carlos Antón, David Castro, Estela Artacho, Fernando Lara, Jacobo Martín Fernández, Jaume Canela, Jorge Naranjo, Marta Tarín, Maryse Capdepuy, Mercedes Ruiz, Olga Martín Sancho y Rebeca Amieva Edita Academia de las Artes y las Ciencias Cinematográficas de España © Academia de las Artes y las Ciencias Cinematográficas de España © Marta Portalés Oliva y Dr. -

Alfonso Sánchez Diego Galán Versión Española

ACADEMIA Revista del Cine Español nº 169 JULIO / AGOSTO 2010 4 € Primer Premio de Comunicación Alfonso Sánchez Diego Galán Versión española A CADEMIA DE LAS A RTES Y LAS C IENCIAS C INEMATOGRÁ FICAS DE E SPAÑA ACADEMIA REVISTA DEL CINE ESPAÑOL DIRECTOR: ARTURO GIRÓN [email protected] PRODUCCIÓN: ANA ROS [email protected] EDICIÓN: ELOÍSA VILLAR [email protected] REDACCIÓN ([email protected]): ELOÍSA VILLAR, ANA ROS, CHUSA L. MONJAS [email protected] DOCUMENTACIÓN: MARÍA PASTOR [email protected] DISEÑO: ALBERTO LABARGA [email protected] IMPRIME: Gráficas 82 D.L. BU–217/95. ISSN 1136–8144 ACADEMIA, REVISTA DEL CINE ESPAÑOL, NO SE SOLIDARIZA NECESARIAMENTE CON LAS OPINIONES EXPUESTAS EN LOS ARTÍCULOS QUE PUBLICA, CUYA RESPONSABILIDAD CORRESPONDE EXCLUSIVAMENTE A LOS AUTORES. EDITA: Carmen Martín maquilla a Estrellita Castro durante el rodaje de Los misterios de Tánger C/ Zurbano, 3. 28010 Madrid Tel. 91 5934648 y 91 4482321. Fax: 91 5931492 Grandes en la sombra Internet: www.academiadecine.com Cinco profesionales que han dedicado toda su vida al mundo del cine. Un reconocimiento a muchos años de E-mail: [email protected] trabajo, a largas carreras al servicio de la industria cinematográfica. Un homenaje que abre las puertas de la PRESIDENTE: ÁLEX DE LA IGLESIA 14 Academia a los rostros menos conocidos del celuloide. VICEPRESIDENTES: ICÍAR BOLLAÍN, EMILIO A. PINA, TERESA ENRICH González Sinde. La Casa de la India consigue el premio en su decimosegunda edición por la JUNTA DIRECTIVA: PEDRO EUGENIO DELGADO, MANUEL organización del Festival de Cine Español de la India. Un esfuerzo por la difusión en el país asiático de nuestra CRISTÓBAL RODRÍGUEZ (ANIMACIÓN), ENRIQUE URBIZU, cinematografía más reciente. -

Course Number and Title

Centro Universitario Internacional ART 330 Historia del cine español en democracia Samuel Neftalí Fernández-Pichel Información de la asignatura: Oficina: Edificio 25, planta baja Primavera de 2017 Email: [email protected] Miércoles Tutorías: Lunes y miércoles , 9:45-10:15 (previa cita) 16:00 – 18:50 Descripción de la asignatura La historia del cine en el Estado español experimenta un proceso de transformación con la llegada de la democracia tras la muerte del dictador Francisco Franco en 1975. La nueva realidad política y social del país, junto a la abolición definitiva de la censura y las sucesivas medidas de regulación del audiovisual, provocan la homologación del cine español en el espacio cultural europeo y mundial, con sus logros y sus fracasos. Partiendo de una breve aproximación a las tendencias cinematográficas (sub)nacionales hasta los albores de la democracia, el curso analizará la evolución histórica del cine español de las últimas cuatro décadas. Este programa pretende familiarizar al alumno con los componentes fundamentales de la industria cinematográfica española a través de su historia (directores, guionistas, actores, películas, estéticas, tendencias, etc.). En tal proceso, partiremos del análisis de los textos fílmicos (las películas) para identificar en ellas las huellas de los diferentes contextos de producción, así como de los dispositivos narrativos, formales e ideológicos que los conforman y que establecen nexos entre las diferentes épocas, estéticas y textos particulares. Conocimientos previos requeridos Este es un curso introductorio al cine español de las últimas cuatro décadas que, por sus características (dificultad de las lecturas, dinámica de debates, terminología, etc.), está principalmente diseñado para estudiantes con un nivel avanzado de español (B2, MCER). -

Dossier Completo

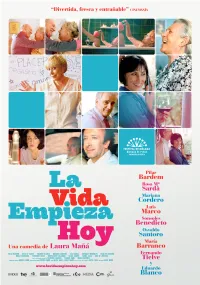

La vida empieza hoy Tienen experiencia, tienen ganas de hacer cosas, tienen una vida sexual activa… Y sobre todo... Tienen tiempo!!! SINOPSIS Un grupo de hombres y mujeres de la tercera edad asiste a clases de sexo para continuar teniendo una vida sexual plena. En ellas comparten deseos y preocupaciones. Pepe, tiene disfunción eréctil provocada por el estrés de la jubilación y quiere volver a ser el hombre que era; Herminia cree que es frígida pero descubre que su problema ha sido estar siempre con el hombre equivocado. A Julián le gustan las mujeres y sobre todo Herminia. Ambos se entienden tan bien en la cama, que deciden emprender una relación puramente sexual; Juanita tiene la certeza de que se va a morir, pero cuando se separa de su difunto marido, decide rehacer su vida... En la clase de sexo, Olga, la profesora, les ayuda a hacer frente a esos problemillas generados por la edad. Pero para eso, tendrán que hacer los deberes... Una historia coral, narrada en tono de comedia en la que padres, hijos y nietos se cruzan continuamente en una gran ciudad donde les resulta difícil encontrar su lugar. La vida empieza hoy FICHA ARTÍSTICA PILAR BARDEM Juanita ROSA Mª SARDÁ Olga MARIANA CORDERO Rosita LLUÍS MARCO Pepe SONSOLES BENEDICTO Herminia OSVALDO SANTORO Julián MARÍA BARRANCO Nina FERNANDO TIELVE Kim MONTSERRAT SALVADOR Carmen SÍLVIA SABATÉ Nuria ISABEL OSCA Mercedes ANA Mª VENTURA Adelita Y EDUARDO BLANCO Alfredo Con la colaboración especial de FRANCESC GARRIDO FERRÁN RAÑÉ MARC MARTÍNEZ La vida empieza hoy FICHA TÉCNICA DIRECTORA LAURA MAÑÁ GUIÓN ALICIA LUNA y LAURA MAÑÁ Basado en una idea original de ALICIA LUNA PRODUCTOR EJECUTIVO QUIQUE CAMÍN PRODUCTOR DELEGADO ANTONI CAMÍN DIRECTOR DE FOTOGRAFÍA MARIO MONTERO MONTAJE LUCAS NOLLA MÚSICA XAVIER CAPELLAS DIRECTOR DE ARTE BALTER GALLART DIRECTORA DE PRODUCCIÓN BET PUJOL SONIDO DANI FONTRODONA JEFE DE PRODUCCIÓN VALENTÍ CLOSAS FIGURINISTA MARÍA GIL MAQUILLAJE MONTSE BOQUERAS PELUQUERÍA SERGIO PÉREZ REPARTO LAURA CEPEDA MAKING OF JAVIER CALVO Formato y Duración 35mm (rodada en HD), Color, 90 min. -

The Seductive Narrative Appeal of a Madwoman Juana 'La Loca'

Hipertexto 17 Invierno 2013 pp. 3-15 The Seductive Narrative Appeal of a Madwoman Juana ‘la Loca’ and Excessive Femininity Alexandra Fitts University of Alaska Fairbanks Hipertexto uana of Castilla (1479-1555), known as Juana la Loca, is one of the most intriguing J and ambiguous figures of Spanish history. Though she was the first Spanish monarch to unite Castilla and Aragón under one crown and held the title of queen from 1516 until her death, she never truly ruled and was confined in the castle of Tordesillas for the last forty-six years of her life.1 Juana has always captured the Spanish imagination, and over time her image has gone through many revisions. For centuries the accepted view of Juana was that she was driven mad by the early death of her beloved husband, Felipe “el Hermoso.” A popular story and artistic subject has her traveling through Spain with his coffin, refusing to part with his decomposing body, which she would periodically uncover and kiss. Later renditions allow for a more political interpretation, presenting her as a pawn in the machinations of her father, husband, and son. In the twentieth century, Juana emerges as a proto-feminist, persecuted for failing to fit into the predetermined mold of a woman of her time and position. Still more recently, she has become an increasingly sexualized figure whose appetites (healthy, but excessively female, and ultimately unacceptable) were labeled insanity. It is not surprising that interpretations of Juana’s plight and her madness alter as the historians, biographers, artists and writers who are fascinated by her reflect the understandings and preoccupations of their own times. -

(Coproducción Uruguay-España) Federico Veiroj Contemporary

PELICULAS ESPAÑOLAS EN FESTIVALES ‐ SEPTIEMBRE 2018 Título Director Seccion Premio Belmonte Contemporary Federico Veiroj TORONTO INTERNATIONAL (Coproducción Uruguay-España) World Cinema FILM FESTIVAL El Angel Contemporary Luis Ortega (Coproducción Argentina-España) World Cinema Everybody Knows 6 - 16 de septiembre Asghar Farhadi Gala Presentations (Coproducción España-Francia-Italia) https://www.tiff.net Julio Iglesias's House Natalia Marín Wavelengths Life Itself Dan Fogelman Gala Presentations (Coproducción España-EEUU) Quién te cantará Contemporary (Coproducción España-Francia) Carlos Vermut World Cinema The Realm Contemporary Rodrigo Sorogoyen (Coproducción España-Francia) World Cinema The Sisters Brothers Special Jacques Audiard (Coproducción USA-Francia-Rumanía-España) Presentations Those Who Desire Elena López Riera Wavelengths (Coproducción Suiza-España) Words, Planets Laida Lertxundi Wavelengths El contenido que se ofrece es meramente informativo y carece de efectos vinculantes para la Administración. The content offered herein is merely informative and not legally binding as far as the Administration is concerned. Título Director Seccion Premio FEFFS FESTIVAL EUROPEEN ANOTHER DAY OF LIFE Raul De La Fuente, Damian Animated Film DO FILM FANTASTIQUE DE (Coproducción Alemania-Bélgica-España-Polonia) Nenow Competition STRASBOURG 14 - 23 de septiembre http://strasbourgfestival.com /en Título Director Seccion Premio El Reino FESTIVAL DE SAN SEBASTIÁN Sección Oficial (Coproducción España-Francia) Rodrigo Sorogoyen Concha de Oro a la -

FORTHCOMING in SPAIN IS (STILL) DIFFERENT, Eds

FORTHCOMING IN SPAIN IS (STILL) DIFFERENT, eds. Jaume Martí Olivella and Eugenia Afinoguenova, U of Minnesota P: Toppling the Xenolith: The Reconquest of Spain from the Uncanny Other in Iberian Film since World War Two Patricia Hart, Purdue University 1. The Others Ser ibero, ser ibero es una cosa muy seria, soy altivo y soy severo porque he nacido en Iberia. Y al que diga lo contrario Y al que ofenda a mi terruño Lo atravieso atrabilario Con esta daga que empuño Fray Apócrifo de la Cruz1 Long before Ruy Díaz de Vivar drove the Moors from Valencia and returned her fragrant orange groves to an ungrateful Alfonso VI—and long before anyone could suspect that in 1983 Angelino Fons would cast lion-tamer Ángel Cristo as the title character in his 1983 comedy, El Cid Cabreador—Iberian popular culture was often obsessed with monarchic, dictatorial, or hegemonic views of what is “us” and what is “other,” and with good reason! That catch-all category, iberos, was loosely used to name all of those prehistoric people living on the Peninsula before they had been invaded by just about every enterprising group armed with swords or something to sell. Celts, Phoenicians, Carthaginians on pachyderms, Greeks, Romans, suevos, alanos Vandals, Visigoths, Moors… no wonder the xenos was traditionally a cause for concern! The blunt, politically- and financially-expedient, medieval interest in the so-called “purity” of blood” and antiquity of Christian conversion served to consolidate power, property, and social stratification. 1 Better known as Moncho Alpuente. Turismo y cine Patricia Hart—Purdue—2 It is essential to keep this in mind as we talk about tourism on film, as for milenia, the idea of travel for pleasure was something reserved for a very tiny elite (and their servants).