Country Advice Colombia – COL38771 – M19– Bucaramanga

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quaternary Activity of the Bucaramanga Fault in the Depart- Ments of Santander and Cesar

Volume 4 Quaternary Chapter 13 Neogene https://doi.org/10.32685/pub.esp.38.2019.13 Quaternary Activity of the Bucaramanga Fault Published online 27 November 2020 in the Departments of Santander and Cesar Paleogene Hans DIEDERIX1* , Olga Patricia BOHÓRQUEZ2 , Héctor MORA–PÁEZ3 , 4 5 6 Juan Ramón PELÁEZ , Leonardo CARDONA , Yuli CORCHUELO , 1 [email protected] 7 8 Jaír RAMÍREZ , and Fredy DÍAZ–MILA Consultant geologist Servicio Geológico Colombiano Dirección de Geoamenazas Abstract The 350 km long Bucaramanga Fault is the southern and most prominent Grupo de Trabajo Investigaciones Geodésicas Cretaceous Espaciales (GeoRED) segment of the 550 km long Santa Marta–Bucaramanga Fault that is a NNW striking left Dirección de Geociencias Básicas Grupo de Trabajo Tectónica lateral strike–slip fault system. It is the most visible tectonic feature north of latitude Paul Krugerstraat 9, 1521 EH Wormerveer, 6.5° N in the northern Andes of Colombia and constitutes the western boundary of the The Netherlands 2 [email protected] Maracaibo Tectonic Block or microplate, the southeastern boundary of the block being Servicio Geológico Colombiano Jurassic Dirección de Geoamenazas the right lateral strike–slip Boconó Fault in Venezuela. The Bucaramanga Fault has Grupo de Trabajo Investigaciones Geodésicas Espaciales (GeoRED) been subjected in recent years to neotectonic, paleoseismologic, and paleomagnetic Diagonal 53 n.° 34–53 studies that have quantitatively confirmed the Quaternary activity of the fault, with Bogotá, Colombia 3 [email protected] eight seismic events during the Holocene that have yielded a slip rate in the order of Servicio Geológico Colombiano Triassic Dirección de Geoamenazas 2.5 mm/y, whereas a paleomagnetic study in sediments of the Bucaramanga alluvial Grupo de Trabajo Investigaciones Geodésicas fan have yielded a similar slip rate of 3 mm/y. -

Centros De Atención Ciudadana Unidades De Reacción Inmediata

Centros de Atención Ciudadana Unidades de Reacción Inmediata- URI Seccional Municipio / Dirección Teléfono Localidad Armenia Armenia Palacio de Justicia P - 1 57(6) 744 3672 Barranquilla Barranquilla Cll. 41 No. 41 - 69 57(5) 344 0030 Bogotá Ciudad Bolívar Cll. 54 Sur No. 16 - 03 57(1) 760 3644 Bogotá Usaquén Cr. 32 No. 13 A 20 Bogotá Paloquemao Av. 19 No. 29 - 75 P - 1 57(1) 297 1177 Bogotá Engativá Cr. 78 A No. 77 A - 62 57(1) 430 3318 Bogotá Kennedy Cr. 72 J No. 36 - 56 / 58 57(1) 299 3515 Sur Bucaramanga Bucaramanga Cr. 19 No. 24 - 61 P - 1 57(7) 652 2222 Ext. 2103 - 2114 -2110 Bucaramanga Barrancabermeja Palacio de Justicia 57(7) 621 3652 Buga Buga Cr. 9 Bis No. 17 - 71 57(2) 237 3064 Buga Buenaventura Cll. 3 No. 3 A - 01 57(2) 240 1541 Buga Cartago Cr. 5 No. 12 A - 23 57(2) 214 6061 - 57(2) 213 2201 Buga Tuluá Cll. 23 No. 26 - 31 57(2) 225 8561 Cali Cali Cll. 11 Cr. 60 Santa Anita 57(2) 312 5327 Cali Palmira Cr. 33 No. 30 - 01 57(2) 272 8253 - 57(2)275 6980 Cali Yumbo Cll. 4 No. 2 -24 57(2)669 5943 - 57(2)669 5945 Cali Siloé Cr. 52 Cll. 2 Estación Lido 57(2)513 5368 Cali Aguablanca Cr. 26 M Cll. 73 Los 57(2)422 9653 Mangos Cartagena Cartagena Crespo Cll. 66 No. 4 - 86 57(5) 656 2751 P - 1 Cúcuta Cúcuta Av. Gran Colombia 2 E - 57(7) 5775058 91 Cundinamarca Girardot Caja Agraria P - 3 57(1) 835 2375 Cundinamarca Fusagasugá Casa del Molino Puente 57(1) 867 2180 del Aguila Cundinamarca Soacha Cr. -

Ordenamiento Territorial Del Departamento De Santander

Lineamientos y Directrices de Ordenamiento Territorial del Departamento de Santander Actualización de Lineamientos y Directrices de Ordenamiento Territorial del Departamento de Santander Richard Alfonso Aguilar Villa Comité Interinstitucional GOBERNADOR Gobernación de Santander – Universidad Santo Tomás Departamento de Santander Sergio Isnardo Muñoz Villarreal Sergio Isnardo Muñoz Villarreal Secretario de Planeación Departamental Secretario de Planeación Departamental fr. Samuel E. Forero Buitrago, O.P. Gabinete Departamental Rector Universidad Santo Tomás, Seccional Bucaramanga Yaneth Mojica Arango Secretaria de Interior fr. Rubén Darío López García, O.P. Vicerrector Administrativo y Financiero, Seccional Carlos Arturo Ibáñez Muñoz Bucaramanga Secretario de Vivienda y Hábitat Sustentable Coordinador Ejecutivo del proyecto Margarita Escamilla Rojas Néstor José Rueda Gómez Secretaria de Hacienda Director Científico del Proyecto Claudia Yaneth Toledo Margarita María Ayala Cárdenas Secretario de Infraestructura Directora Centro de Proyección Social, Supervisora del proyecto, USTA, Seccional Gladys Helena Higuera Sierra Bucaramanga Secretaria General Carlos Andrés Pinzón Serpa Maritza Prada Holguín Coordinador Administrativo Secretaria de Cultura y Turismo Claudia Patricia Uribe Rodríguez John Abiud Ramírez Barrientos Decana Facultad Arquitectura Secretario Desarrollo John Manuel Delgado Nivia Alberto Chávez Suárez Director Prospectiva Territorial de Santander Secretario de Educación Juan José Rey Serrano Edwin Fernando Mendoza Beltrán, Secretario Salud Supervisor del proyecto, Gobernación Omar Lengerke Pérez Directivos Universidad Santo Tomás, Seccional Secretario de las TIC Bucaramanga Ludwing Enrique Ortero Ardila fr. Samuel E. Forero Buitrago, O.P. Secretario de Agricultura Rector Universidad Santo Tomás, Seccional Bucaramanga Honorables Miembros de la Asamblea Departamental Luis Fernando Peña Riaño fr. Mauricio Cortés Gallego, O.P. Carlos Alberto Morales Delgado Vicerrector Académico USTA Yolanda Blanco Arango José Ángel Ibáñez Almeida fr. -

Redalyc.Institucionalización Organizativa Y Procesos De

Estudios Políticos ISSN: 0121-5167 [email protected] Instituto de Estudios Políticos Colombia Duque Daza, Javier Institucionalización organizativa y procesos de selección de candidatos presidenciales en los partidos Liberal y Conservador colombianos 1974-2006 Estudios Políticos, núm. 31, julio-diciembre, 2007 Instituto de Estudios Políticos Medellín, Colombia Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=16429059008 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Institucionalización organizativa y procesos de selección de candidatos presidenciales en los partidos Liberal y Conservador colombianos 1974-2006∗ Organizational Institutionalization and Selection Process of Presidential Candidates in the Liberal and Conservative colombian Parties Javier Duque Daza∗ Resumen: En este artículo se analizan los procesos de selección de los candidatos profesionales en los partidos Liberal y Conservador colombianos durante el periodo 1974-2006. A partir del enfoque de la institucionalización organizativa, el texto aborda las características de estos procesos a través de tres dimensiones analíticas: la existencia de reglas de juego, su grado de aplicación y acatamiento por parte de los actores internos de los partidos. El argumento central es que ambos partidos presentan un precario proceso de institucionalización organizativa, el cual se expresa en la debilidad de sus procesos de rutinización de las reglas internas. Finaliza mostrando cómo los sucedido en las elecciones de 2002 y de 2006, en las que se puso en evidencia que el predominio histórico de los partidos Liberal y Conservador estaba siendo disputado por nuevos partidos, los ha obligado a encaminarse hacia su reestructuración y hacia la búsqueda de mayores niveles de institucionalización organizativa. -

A Land Title Is Not Enough

A LAND TITLE IS NOT ENOUGH ENsuRINg sustAINAblE lANd REstItutIoN IN ColoMbIA Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2014 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom © Amnesty International 2014 Index: AMR 23/031/2014 English Original language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover photo : A plot of land in El Carpintero, Cabuyaro Municipality, Meta Department. Most of the peasant farmers from El Carpintero were forced to flee their homes following a spate of killings and forced disappearances of community members carried out by paramilitary groups in the late 1990s. -

La Paz Que No Llegó: Enseñanzas De Una Negociación Fallida

59 la paz que no llegó: enseñanzas de una negociación fallida juan manuel ospina restrepo* La década de los noventa pasará a la his- cado. Años en los cuales la corrupción se toria como una de las más difíciles y con- desbordó, invadió al conjunto de la acti- fusas que haya vivido Colombia. Años de vidad ciudadana y se convirtió en la reali- grandes ilusiones e inconmensurables frus- dad más deslegitimadora de nuestras traciones. De nueva Constitución y de golpeadas instituciones. En el mundo de masacres y desplazamientos sin fin. Una hoy los gobiernos y aún los regímenes década donde conocimos mejor nuestras políticos se derrumban ante todo por la falencias internas pero también nuestras fuerza de la corrupción, que alimenta la posibilidades. Una década que en lo exte- pobreza y el marginamiento en medio de rior nos enfrentó al desafiante, amenazante la abundancia. y engañoso escenario de la globalización. Los colombianos hemos cambiado. Que en lo interno nos enfrentó a una gue- De eso no hay duda. Ya no somos lo que rrilla que salió de las penumbras selváti- éramos pero todavía no tenemos nuestra cas y de las lejanías de nuestras fronteras nueva piel. Somos conscientes de que lo agrícolas para hacer sentir su influencia y que viene de atrás se agotó; que no hay sus apetencias de poder. De un narcotrá- espacio ni razones para la nostalgia. Que- fico que se enseñorea por el país y de un remos eso sí, tener certidumbres, clarida- fundamentalismo ideológico que, olvidan- des. Por eso la gente emigra. Por eso la do toda esa realidad, pretende que Colom- gente se interroga e interroga. -

On Birds of Santander-Bio Expeditions, Quantifying The

Facultad de Ciencias ACTA BIOLÓGICA COLOMBIANA Departamento de Biología http://www.revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/actabiol Sede Bogotá ARTÍCULO DE INVESTIGACIÓN / RESEARCH ARTICLE ZOOLOGÍA ON BIRDS OF SANTANDER-BIO EXPEDITIONS, QUANTIFYING THE COST OF COLLECTING VOUCHER SPECIMENS IN COLOMBIA Sobre las aves de las expediciones Santander-Bio, cuantificando el costo de colectar especímenes en Colombia Enrique ARBELÁEZ-CORTÉS1 *, Daniela VILLAMIZAR-ESCALANTE1 , Fernando RONDÓN-GONZÁLEZ2 1Grupo de Estudios en Biodiversidad, Escuela de Biología, Universidad Industrial de Santander, Carrera 27 Calle 9, Bucaramanga, Santander, Colombia. 2Grupo de Investigación en Microbiología y Genética, Escuela de Biología, Universidad Industrial de Santander, Carrera 27 Calle 9, Bucaramanga, Santander, Colombia. *For correspondence: [email protected] Received: 23th January 2019, Returned for revision: 26th March 2019, Accepted: 06th May 2019. Associate Editor: Diego Santiago-Alarcón. Citation/Citar este artículo como: Arbeláez-Cortés E, Villamizar-Escalante D, and Rondón-González F. On birds of Santander-Bio Expeditions, quantifying the cost of collecting voucher specimens in Colombia. Acta biol. Colomb. 2020;25(1):37-60. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15446/abc. v25n1.77442 ABSTRACT Several scientific reasons support continuing bird collection in Colombia, a megadiverse country with modest science financing. Despite the recognized value of biological collections for the rigorous study of biodiversity, there is scarce information on the monetary costs of specimens. We present results for three expeditions conducted in Santander (municipalities of Cimitarra, El Carmen de Chucurí, and Santa Barbara), Colombia, during 2018 to collect bird voucher specimens, quantifying the costs of obtaining such material. After a sampling effort of 1290 mist net hours and occasional collection using an airgun, we collected 300 bird voucher specimens, representing 117 species from 30 families. -

Costos De Referencia Por Tonelada Para Un Tractocamión

Costos de referencia por tonelada para un tractocamión A. Costo de traslado por tonelada: costo de movilizar el vehículo en un origen destino (excluye el costo de las horas de espera, carga y descarga): Destino Origen ARMENIA BARRANQUILLA BOGOTA BUCARAMANGA BUENAVENTURA CALI CARTAGENA CARTAGO (VALLE) CUCUTA DUITAMA FLORENCIA IBAGUE IPIALES-NARIÑO MANIZALES MEDELLÍN MOCOA MONTERIA NEIVA PASTO PEREIRA POPAYAN RIOHACHA SANTA MARTA SINCELEJO SOGAMOSO-BOYACA TUMACO VALLEDUPAR VILLAVICENCIO YOPAL ARMENIA 0 147,088.02 51,435.21 90,867.55 37,188.58 25,244.58 141,831.01 6,226.27 129,564.08 91,604.83 81,360.80 15,977.40 110,146.80 16,158.00 53,478.20 95,267.72 106,598.44 45,584.61 93,023.40 6,714.30 48,372.69 188,134.49 146,487.17 116,749.99 84,415.54 140,460.66 149,713.92 77,904.60 110,856.13 BARRANQUILLA 147,088.02 0 137,272.09 83,390.47 178,630.52 166,668.91 14,070.86 144,632.31 96,450.85 143,677.71 224,939.36 142,337.02 249,811.24 129,831.66 101,648.62 238,876.87 50,133.48 164,545.22 234,243.72 134,418.54 187,573.53 42,586.17 11,910.01 32,809.81 139,761.06 277,784.90 46,770.83 164,488.22 168,392.50 BOGOTA 51,435.21 138,233.82 0 55,255.22 89,187.92 77,043.29 135,233.75 54,842.99 92,171.94 35,006.67 84,220.29 31,395.20 160,911.25 49,692.97 62,323.89 98,130.08 118,254.94 47,110.43 145,233.02 55,359.04 99,123.05 174,708.22 130,892.80 128,776.44 30,340.24 194,100.54 136,279.15 21,374.71 60,821.25 BUCARAMANGA 90,867.55 83,390.47 55,255.22 0 131,675.22 117,840.86 88,596.13 91,558.30 34,641.23 58,901.60 148,179.89 73,840.73 204,654.47 79,268.42 69,881.52 -

Complejo Yariguíes 0 0 N " N

73°40'0"W 73°35'0"W 73°30'0"W 73°25'0"W 73°20'0"W 73°15'0"W 1050000 1060000 1070000 1080000 1090000 1100000 CDMB Complejo de Páramos Yariguíes Distrito Santanderes 0 0 Sector Cordillera Oriental 0 0 0 0 0 0 5 5 2 2 1 1 CE-ST-YRG N Convenio Interadministrativo de Asociación (105) 11-103 de 2011 " N " 0 ' 0 ' 0 0 5 ° 5 ° 6 6 MINISTERIO DE AMBIENTE Y DESARROLLO SOSTENIBLE INSTITUTO DE INVESTIGACIÓN DE RECURSOS BIOLÓGICOS ALEXANDER VON HUMBOLDT 2012 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Con el apoyo de: 4 4 2 2 1 1 N " N " 0 ' 0 ' 5 5 4 ° 4 ° 6 6 Dirección Técnica Carlos E. Sarmiento Pinzón Procesamiento y análisis Diana P. Ramírez Aguilera, Luisa F. Pinzón Flórez, Jessica A. Zapata Jiménez, July A. Medina Triana, Camilo E. Cadena Vargas, María V. Sarmiento Giraldo Asesoría Científica Antoine Cleef, Robert Hofstede, David Rivera Ospina Con la contribución de Corporaciones Autónomas Regionales y de Desarrollo Sostenible 0 0 Jimena Cortés Duque, Claudia P. Fonseca Tobián, Zoraida Fajardo Rodríguez, Edgar Olaya Ospina, 0 0 0 0 0 0 Juliana E. Rodríguez Cajamarca. 3 3 2 2 1 1 N " N " 0 ' 0 ' 0 0 4 Localización General ° 4 6 ° 6 Nacional Regional 82°0'0"W 75°0'0"W 68°0'0"W 74°0'0"W 73°0'0"W Mar Caribe CSB CORPONOR CDMB N N " " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° ° CORANTIOQUIA 7 7 Panamá N N " " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° ° 8 Venezuela 8 CAS Oceáno Pacífico N N " " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° ° 1 1 N N " " Convenciones 0 0 ' Ecuador Brasil ' 0 0 0 0 ° ° 6 6 0 0 Complejo Yariguíes 0 0 N " N 0 0 CORPOBOYACA " 0 ' Otros Complejos de Páramos 0 ' 2 2 5 5 2 2 3 ° 3 Corporación Autónoma Regional 1 1 ° 6 6 o de Desarrollo Sostenible Límite departamental Perú 0 7.5 15 30 45 0 110 220 440 660 CAR S S Kilometers " Kilometros " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° ° 6 6 82°0'0"W 75°0'0"W 68°0'0"W 74°0'0"W 73°0'0"W SANTANDER CAS Parámetros cartográficos Fuentes: Referencia Cartográfica IGAC.2012. -

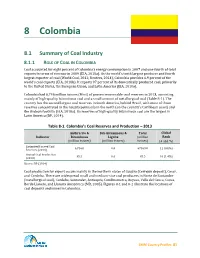

Chapter 8: Colombia

8 Colombia 8.1 Summary of Coal Industry 8.1.1 ROLE OF COAL IN COLOMBIA Coal accounted for eight percent of Colombia’s energy consumption in 2007 and one-fourth of total exports in terms of revenue in 2009 (EIA, 2010a). As the world’s tenth largest producer and fourth largest exporter of coal (World Coal, 2012; Reuters, 2014), Colombia provides 6.9 percent of the world’s coal exports (EIA, 2010b). It exports 97 percent of its domestically produced coal, primarily to the United States, the European Union, and Latin America (EIA, 2010a). Colombia had 6,746 million tonnes (Mmt) of proven recoverable coal reserves in 2013, consisting mainly of high-quality bituminous coal and a small amount of metallurgical coal (Table 8-1). The country has the second largest coal reserves in South America, behind Brazil, with most of those reserves concentrated in the Guajira peninsula in the north (on the country’s Caribbean coast) and the Andean foothills (EIA, 2010a). Its reserves of high-quality bituminous coal are the largest in Latin America (BP, 2014). Table 8-1. Colombia’s Coal Reserves and Production – 2013 Anthracite & Sub-bituminous & Total Global Indicator Bituminous Lignite (million Rank (million tonnes) (million tonnes) tonnes) (# and %) Estimated Proved Coal 6,746.0 0.0 67469.0 11 (0.8%) Reserves (2013) Annual Coal Production 85.5 0.0 85.5 10 (1.4%) (2013) Source: BP (2014) Coal production for export occurs mainly in the northern states of Guajira (Cerrejón deposit), Cesar, and Cordoba. There are widespread small and medium-size coal producers in Norte de Santander (metallurgical coal), Cordoba, Santander, Antioquia, Cundinamarca, Boyaca, Valle del Cauca, Cauca, Borde Llanero, and Llanura Amazónica (MB, 2005). -

Pdf | 271.02 Kb

United Nations S/2019/1017 Security Council Distr.: General 31 December 2019 Original: English Children and armed conflict in Colombia Report of the Secretary-General Summary The present report, submitted pursuant to Security Council resolution 1612 (2005) and subsequent resolutions, is the fourth report of the Secretary-General on children and armed conflict in Colombia and covers the period from 1 July 2016 to 30 June 2019. The report provides information on the six grave violations against children, on parties to conflict responsible, where identified, and on progress made in the protection of children affected by armed conflict. The reporting period was marked by the implementation of the Final Agreement for Ending the Conflict and Building a Stable and Lasting Peace (S/2017/272, annex II) between the Government of Colombia and the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia-Ejército del Pueblo (FARC-EP), which put an end to a five-decade-long conflict. A decrease in the total number of grave violations against children was documented and can be explained in part by the signature of the peace agreement and the subsequent demobilization of the largest armed group in the country. Over the same period, however, other armed groups expanded their territorial presence, including in areas vacated by FARC-EP, and FARC-EP dissident groups emerged. These developments have continued to expose children to grave violations, in particular recruitment and use and sexual violence. Highlighted in the report are the efforts made by the Government of Colombia to strengthen the framework to respond to, end and prevent grave violations against children, including through prevention strategies. -

FULLTEXT01.Pdf

1 Cover photo: José Ramón Gomez, Arauca, 2012 Front page designed by: Manuela Giraldo 'When an Indigenous People disappears, a whole world is extinguished forever, along with its culture, spirituality, language, ancestral knowledge and traditional practices ... The survival of Indigenous Peoples with dignity is all in our hands.” National Indigenous Organization of Colombia (ONIC) "We are not myths of the past neither ruins in the jungle. We are people and we want to be respected…” Rigoberta Menchu Tum 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................................. 5 PREFACE .................................................................................................................................... 6 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................................................................................................ 7 ACRONYMS ............................................................................................................................... 8 1.1 Aim and Research Question ............................................................................................ 10 1.2 Theoretical Framework ................................................................................................... 10 1.2.1 Structural Violence ................................................................................................ 11 1.2.2 Civilians Targeted by GAO ML..........................................................................