18 Chromosome Chapter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

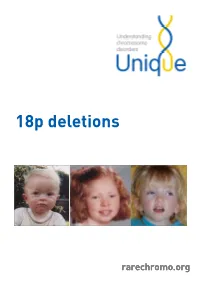

18P Deletions FTNW

18p deletions rarechromo.org 18p deletions A deletion of 18p means that the cells of the body have a small but variable amount of genetic material missing from one of their 46 chromosomes – chromosome 18. For healthy development, chromosomes should contain just the right amount of material – not too much and not too little. Like most other chromosome disorders, 18p deletions increase the risk of birth defects, developmental delay and learning difficulties. However, the problems vary and depend very much on what genetic material is missing. Chromosomes are made up mostly of DNA and are the structures in the nucleus of the body’s cells that carry genetic information (known as genes), telling the body how to develop, grow and function. Base pairs are the chemicals in DNA that form the ends of the ‘rungs’ of its ladder-like structure. Chromosomes usually come in pairs, one chromosome from each parent. Of these 46 chromosomes, two are a pair of sex chromosomes, XX (a pair of X chromosomes) in females and XY (one X chromosome and one Y chromosome) in males. The remaining 44 chromosomes are grouped in 22 pairs, numbered 1 to 22 approximately from the largest to the smallest. Each chromosome has a short ( p) arm (shown at the top in the diagram on the facing page) and a long ( q) arm (the bottom part of the chromosome). People with an 18p deletion have one intact chromosome 18, but the other is missing a smaller or larger piece from the short arm and this can affect their learning and physical development. -

Association of Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia and Hiatal Hernia with Tetrasomy 18P

Accepted Manuscript Association of Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia and Hiatal Hernia with Tetrasomy 18p Jamir Arlikar , MD Victor McKay , MD Paul Danielson , MD PII: S2213-5766(14)00068-2 DOI: 10.1016/j.epsc.2014.05.006 Reference: EPSC 221 To appear in: Journal of Pediatric Surgery Case Reports Received Date: 25 March 2014 Revised Date: 7 May 2014 Accepted Date: 17 May 2014 Please cite this article as: Arlikar J, McKay V, Danielson P, Association of Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia and Hiatal Hernia with Tetrasomy 18p, Journal of Pediatric Surgery Case Reports (2014), doi: 10.1016/j.epsc.2014.05.006. This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain. ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT ASSOCIATION OF CONGENITAL DIAPHRAGMATIC HERNIA AND HIATAL HERNIA WITH TETRASOMY 18P Running title: “CDH and Hiatal Hernia with Tetrasomy 18p” Jamir Arlikar, MD*, Victor McKay, MD**, and Paul Danielson, MD* Division of Pediatric Surgery* and Division of Neonatology** All Children’s Hospital Johns Hopkins Medicine St. Petersburg, FL MANUSCRIPT Corresponding Author: Paul Danielson, MD All Children’s Hospital Johns Hopkins Medicine 601 Fifth Street South, Dept 70-6600 St. Petersburg, FL 33701 ACCEPTED Tel: 727-767-4109 Fax: 727-767-4346 Email: [email protected] 1 ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT Abstract: We report a case of a newborn with tetrasomy 18p who presents with both a congenital diaphragmatic hernia and a giant hiatal hernia. -

Chromosome 18

Chromosome 18 Description Humans normally have 46 chromosomes in each cell, divided into 23 pairs. Two copies of chromosome 18, one copy inherited from each parent, form one of the pairs. Chromosome 18 spans about 78 million DNA building blocks (base pairs) and represents approximately 2.5 percent of the total DNA in cells. Identifying genes on each chromosome is an active area of genetic research. Because researchers use different approaches to predict the number of genes on each chromosome, the estimated number of genes varies. Chromosome 18 likely contains 200 to 300 genes that provide instructions for making proteins. These proteins perform a variety of different roles in the body. Health Conditions Related to Chromosomal Changes The following chromosomal conditions are associated with changes in the structure or number of copies of chromosome 18. Distal 18q deletion syndrome Distal 18q deletion syndrome occurs when a piece of the long (q) arm of chromosome 18 is missing. The term "distal" means that the missing piece (deletion) occurs near one end of the chromosome arm. The signs and symptoms of distal 18q deletion syndrome include delayed development and learning disabilities, short stature, weak muscle tone ( hypotonia), foot abnormalities, and a wide variety of other features. The deletion that causes distal 18q deletion syndrome can occur anywhere between a region called 18q21 and the end of the chromosome. The size of the deletion varies among affected individuals. The signs and symptoms of distal 18q deletion syndrome are thought to be related to the loss of multiple genes from this part of the long arm of chromosome 18. -

Ring Chromosome 18 in a Patient with Multiple Anomalies* CATHERINE G

J Med Genet: first published as 10.1136/jmg.4.2.117 on 1 June 1967. Downloaded from 7. med. Genet. (1967). 4, 117. Ring Chromosome 18 in a Patient with Multiple Anomalies* CATHERINE G. PALMER, NUZHAT FAREED, and A. DONALD MERRITT From the Department of Medical Genetics, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, Indiana, U.S.A. Ring chromosomes, long of interest in cytogene- At the time of evaluation, the patient (Fig. 1) was 10 tics, have been intensively studied in corn and years old, mentally retarded, and hyperactive. He was Drosophila (McClintock, 1932, 1938; Morgan, 1933; co-operative and able to speak with a three-word syntax. Battacharya, 1950) and also described in Crepis, He had a kyphotic posture and broad-based, balanced gait. The height was 126 cm., weight 212 kg. (both Tulipa, Tradescantia, and other species. In the below the third centile). past few years, a number of reports of ring chromo- His occipital-frontal circumference was 49 cm. (two somes in man have appeared (Table I). We recently standard deviations below the normal). There was encountered a mentally retarded patient with bony roughness over the posterior occipital region. multiple congenital anomalies, in a high proportion The neck had a slight extra fold of skin over the trape- of whose cells we found a ring chromosome 18. zius muscles suggesting webbing, and there was a low The clinical expression of patients with 18 long hairline posteriorly. Ocular findings included an anti- (Lejeune, Berger, Lafourcade, and Rethore, 1966) mongoloid slant, hypertelorism, exotropia, nystagmus, and short arm deletions (Grouchy, Bonnette, and and a normal fundoscopic appearance. -

Abstracts from the 50Th European Society of Human Genetics Conference: Electronic Posters

European Journal of Human Genetics (2019) 26:820–1023 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-018-0248-6 ABSTRACT Abstracts from the 50th European Society of Human Genetics Conference: Electronic Posters Copenhagen, Denmark, May 27–30, 2017 Published online: 1 October 2018 © European Society of Human Genetics 2018 The ESHG 2017 marks the 50th Anniversary of the first ESHG Conference which took place in Copenhagen in 1967. Additional information about the event may be found on the conference website: https://2017.eshg.org/ Sponsorship: Publication of this supplement is sponsored by the European Society of Human Genetics. All authors were asked to address any potential bias in their abstract and to declare any competing financial interests. These disclosures are listed at the end of each abstract. Contributions of up to EUR 10 000 (ten thousand euros, or equivalent value in kind) per year per company are considered "modest". Contributions above EUR 10 000 per year are considered "significant". 1234567890();,: 1234567890();,: E-P01 Reproductive Genetics/Prenatal and fetal echocardiography. The molecular karyotyping Genetics revealed a gain in 8p11.22-p23.1 region with a size of 27.2 Mb containing 122 OMIM gene and a loss in 8p23.1- E-P01.02 p23.3 region with a size of 6.8 Mb containing 15 OMIM Prenatal diagnosis in a case of 8p inverted gene. The findings were correlated with 8p inverted dupli- duplication deletion syndrome cation deletion syndrome. Conclusion: Our study empha- sizes the importance of using additional molecular O¨. Kırbıyık, K. M. Erdog˘an, O¨.O¨zer Kaya, B. O¨zyılmaz, cytogenetic methods in clinical follow-up of complex Y. -

Epigenetic Abnormalities Associated with a Chromosome 18(Q21-Q22) Inversion and a Gilles De La Tourette Syndrome Phenotype

Epigenetic abnormalities associated with a chromosome 18(q21-q22) inversion and a Gilles de la Tourette syndrome phenotype Matthew W. State*†‡, John M. Greally§, Adam Cuker¶, Peter N. Bowersʈ, Octavian Henegariu**, Thomas M. Morgan†, Murat Gunel††, Michael DiLuna††, Robert A. King*, Carol Nelson†, Abigail Donovan¶, George M. Anderson*, James F. Leckman*, Trevor Hawkins‡‡, David L. Pauls§§, Richard P. Lifton†**¶¶, and David C. Ward†¶¶ *Child Study Center and Departments of †Genetics, ¶¶Molecular Biochemistry and Biophysics, **Internal Medicine, ʈPediatrics, and ††Neurosurgery, ¶Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT 06511; §Department of Medicine, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY 10461; §§Psychiatric and Neurodevelopmental Genetics Unit, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Charlestown, MA 02129; and ‡‡Joint Genome Institute, U.S. Department of Energy, Walnut Creek, CA 94598 Contributed by David C. Ward, February 6, 2003 Gilles de la Tourette syndrome (GTS) is a potentially debilitating In addition to linkage and association strategies, multiple neuropsychiatric disorder defined by the presence of both vocal investigators have studied chromosomal abnormalities in indi- and motor tics. Despite evidence that this and a related phenotypic viduals and families with GTS in the hopes of identifying a gene spectrum, including chronic tics (CT) and Obsessive Compulsive or genes of major effect disrupted by the rearrangement (14–16). Disorder (OCD), are genetically mediated, no gene involved in This strategy is predicated on the notion that such patients, disease etiology has been identified. Chromosomal abnormalities although unusual, may help to identify genes that are of conse- have long been proposed to play a causative role in isolated cases quence for a subgroup of patients with GTS, OCD, and CT, and of GTS spectrum phenomena, but confirmation of this hypothesis provide important insights into physiologic pathways that more has yet to be forthcoming. -

Prenatal Diagnosis of Mosaic Tetrasomy 18P in a Case Without Sonographic Abnormalities

IJMCM Case Report Winter 2017, Vol 6, No 1 Prenatal Diagnosis of Mosaic Tetrasomy 18p in a Case without Sonographic Abnormalities Javad Karimzad Hagh1, Thomas Liehr2, Hamid Ghaedi3, Mir Majid Mossalaeie1, Shohreh Alimohammadi4, Faegheh Inanloo Hajiloo1, Zahra Moeini1, Sadaf Sarabi1, Davood Zare-Abdollahi5 1. Parseh Pathobiology & Genetics Laboratory, Tehran, Iran. 2. Jena University Hospital, Friedrich Schiller University, Institute of Human Genetics, Jena, Germany, Iran. 3. Department of medical Genetics, Faculty of Medicine, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. 4. Endometrium and Endometriosis Research Center, Faculty of Medicine, Hamedan University of Medical Sciences, Hamedan, Iran. 5. Genetics Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. Submmited 15 August 2016; Accepted 22 October 2016; Published 17 January 2017 Small supernumerary marker chromosomes (sSMC) are still a major problem in clinical cytogenetics as they cannot be identified or characterized unambiguously by conventional cytogenetics alone. On the other hand, and perhaps more importantly in prenatal settings, there is a challenging situation for counseling how to predict the risk for an abnormal phenotype, especially in cases with a de novo sSMC. Here we report on the prenatal diagnosis of a mosaic tetrasomy 18p due to presence of an sSMC in a fetus without abnormal sonographic signs. For a 26-year-old, gravida 2 (para 1) amniocentesis was done due to consanguineous marriage and concern for Down syndrome, based on borderline risk assessment. Parental karyotypes were normal, indicating a de novo chromosome aberration of the fetus. FISH analysis as well as molecular karyotyping identified the sSMC as an i(18)(pter->q10:q10->pter), compatible with tetrasomy for the mentioned region. -

Abstracts from the 51St European Society of Human Genetics Conference: Electronic Posters

European Journal of Human Genetics (2019) 27:870–1041 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-019-0408-3 MEETING ABSTRACTS Abstracts from the 51st European Society of Human Genetics Conference: Electronic Posters © European Society of Human Genetics 2019 June 16–19, 2018, Fiera Milano Congressi, Milan Italy Sponsorship: Publication of this supplement was sponsored by the European Society of Human Genetics. All content was reviewed and approved by the ESHG Scientific Programme Committee, which held full responsibility for the abstract selections. Disclosure Information: In order to help readers form their own judgments of potential bias in published abstracts, authors are asked to declare any competing financial interests. Contributions of up to EUR 10 000.- (Ten thousand Euros, or equivalent value in kind) per year per company are considered "Modest". Contributions above EUR 10 000.- per year are considered "Significant". 1234567890();,: 1234567890();,: E-P01 Reproductive Genetics/Prenatal Genetics then compared this data to de novo cases where research based PO studies were completed (N=57) in NY. E-P01.01 Results: MFSIQ (66.4) for familial deletions was Parent of origin in familial 22q11.2 deletions impacts full statistically lower (p = .01) than for de novo deletions scale intelligence quotient scores (N=399, MFSIQ=76.2). MFSIQ for children with mater- nally inherited deletions (63.7) was statistically lower D. E. McGinn1,2, M. Unolt3,4, T. B. Crowley1, B. S. Emanuel1,5, (p = .03) than for paternally inherited deletions (72.0). As E. H. Zackai1,5, E. Moss1, B. Morrow6, B. Nowakowska7,J. compared with the NY cohort where the MFSIQ for Vermeesch8, A. -

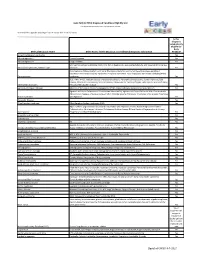

Early ACCESS Diagnosed Conditions List

Iowa Early ACCESS Diagnosed Conditions Eligibility List List adapted with permission from Early Intervention Colorado To search for a specific word type "Ctrl F" to use the "Find" function. Is this diagnosis automatically eligible for Early Medical Diagnosis Name Other Names for the Diagnosis and Additional Diagnosis Information ACCESS? 6q terminal deletion syndrome Yes Achondrogenesis I Parenti-Fraccaro Yes Achondrogenesis II Langer-Saldino Yes Schinzel Acrocallosal syndrome; ACLS; ACS; Hallux duplication, postaxial polydactyly, and absence of the corpus Acrocallosal syndrome, Schinzel Type callosum Yes Acrodysplasia; Arkless-Graham syndrome; Maroteaux-Malamut syndrome; Nasal hypoplasia-peripheral dysostosis-intellectual disability syndrome; Peripheral dysostosis-nasal hypoplasia-intellectual disability (PNM) Acrodysostosis syndrome Yes ALD; AMN; X-ALD; Addison disease and cerebral sclerosis; Adrenomyeloneuropathy; Siemerling-creutzfeldt disease; Bronze schilder disease; Schilder disease; Melanodermic Leukodystrophy; sudanophilic leukodystrophy; Adrenoleukodystrophy Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease Yes Agenesis of Corpus Callosum Absence of the corpus callosum; Hypogenesis of the corpus callosum; Dysplastic corpus callosum Yes Agenesis of Corpus Callosum and Chorioretinal Abnormality; Agenesis of Corpus Callosum With Chorioretinitis Abnormality; Agenesis of Corpus Callosum With Infantile Spasms And Ocular Anomalies; Chorioretinal Anomalies Aicardi syndrome with Agenesis Yes Alexander Disease Yes Allan Herndon syndrome Allan-Herndon-Dudley -

Ring Chromosome 18: a Case Report

IJMCM Case Report Autumn 2014, Vol 3, No 4 Ring Chromosome 18: A Case Report ∗ Shermineh Heydari, Fahimeh Hassanzadeh, Mohammad Hassanzadeh Nazarabadi Department of Medical Genetics, Faculty of Medicine, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran. Submmited 21 August 2014; Accepted 9 September 2014; Published 17 September 2014 Ring chromosomes are rare chromosomal disorders that usually appear to occur de novo. A ring chromosome forms when due to deletion both ends of chromosome fuse with each other. Depending on the amount of chromosomal deletion, the clinical manifestations may be different. So, ring 18 syndrome is characterized by severe mental growth retardation as well as microcephaly, brain and ocular malformations, hypotonia and other skeletal abnormalities. Here we report a 2.5 years old patient with a cleft lip, club foot, mental retardation and cryptorchidism. Chromosomal analysis on the basis of G-banding technique was performed following patient referral to the cytogenetic laboratory. Chromosomal investigation appeared as 46, XY, r(18) (p11.32 q21.32). According to the clinical features of such patients, chromosome investigation is strongly recommended. Key words : Ring chromosome 18, karyotyping, mental retardation ing chromosomes from the cytogenetic point result in the loss of terminal segments and genetic Rof view are rare forms of chromosomal material. This rearrangement causes partial structure abnormalities (1, 2). The ring chromo- monosomy of the distal region of both arms (3, 5). some has been reported for all human Up to 2011 only 70 cases of ring chromosomes chromosomes; their frequency is estimated to be have been reported, in which among them, ring between 1/30000 to 1/60000 (3) and almost 50 chromosome 18 was almost the most common Downloaded from ijmcmed.org at 16:50 +0330 on Monday September 27th 2021 percent of all ring chromosomes originate from (3, 5, 6). -

Mosaic Chromosome 18 Anomaly Delineated in a Child With

Sheth et al. BMC Medical Genomics (2020) 13:141 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12920-020-00796-9 CASE REPORT Open Access Mosaic chromosome 18 anomaly delineated in a child with dysmorphism using a three-pronged cytogenetic techniques approach: a case report Harsh Sheth1, Sunil Trivedi1, Thomas Liehr2, Ketan Patel3, Deepika Jain4, Jayesh Sheth1 and Frenny Sheth1* Abstract Background: A plethora of cases are reported in the literature with iso- and ring-chromosome 18. However, co- occurrence of these two abnormalities in an individual along with a third cell line and absence of numerical anomaly is extremely rare. Case presentation: A 7-year-old female was referred for diagnosis due to gross facial dysmorphism and severe developmental delay. She presented with dysmorphic features, hypo/hyper pigmentation of the skin, intellectual disability and craniosynostosis. G-banding chromosome analysis suggested mos 46,XX,psu idic(18)(p11.2)[25]/46,XX, r(?18)[30]. Additional analysis by molecular karyotyping suggested pure partial deletion of 15 Mb on 18p (18p11.32p11.21). Lastly, multiple rearrangements and detection of a third cell line (ring chr18 and interstitial deletion) of chr18 was observed by multi-color banding. Conclusion: The current study presents a novel case of chromosomal abnormalities pertaining to chromosome 18 across 3 cell lines, which were delineated with a combinatorial approach of diagnostic methods. Keywords: Molecular karyotyping, Microarray, Molecular cytogenetics, Multi-color banding, Ring chromosome r(18), Mosaic chromosome 18, Case report Background phenotype compared to patients with chromosome 18 Structural anomalies involving chromosome 18 long-arm deletions [6]. In most cases, the inherent in- (chr18) are relatively frequently observed with an inci- stability of ring chromosomes leads to loss of the dence at birth of ~ 1/40,000 [1–4]. -

Tetrasomy 18P: Case Report and Review of Literature

Journal name: The Application of Clinical Genetics Article Designation: CASE REPORT Year: 2018 Volume: 11 The Application of Clinical Genetics Dovepress Running head verso: Bawazeer et al Running head recto: Tetrasomy 18p open access to scientific and medical research DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2147/TACG.S153469 Open Access Full Text Article CASE REPORT Tetrasomy 18p: case report and review of literature Shahad Bawazeer1 Abstract: Tetrasomy 18p syndrome (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man 614290) is a very Maha Alshalan2 rare chromosomal disorder that is caused by the presence of isochromosome 18p, which is a Aziza Alkhaldi3 supernumerary marker composed of two copies of the p arm of chromosome 18. Most tetrasomy Nasser AlAtwi3 18p cases are de novo cases; however, familial cases have also been reported. It is characterized Mohammed AlBalwi1,3,4 mainly by developmental delays, cognitive impairment, hypotonia, typical dysmorphic features, and other anomalies. Herein, we report de novo tetrasomy 18p in a 9-month-old boy with dys- Abdulrahman Alswaid2 morphic features, microcephaly, growth delay, hypotonia, and cerebellar and renal malforma- Majid Alfadhel1,2,4 tions. We compared our case with previously reported ones in the literature. Clinicians should 1Developmental Medicine Department, consider tetrasomy 18p in any individual with dysmorphic features and cardiac, skeletal, and King Abdullah International Medical Research Center, King Abdulaziz renal abnormalities. To the best of our knowledge, we report for the first time an association