Comprehensive Debt Retirement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Corporate Bonds and Debentures

Corporate Bonds and Debentures FCS Vinita Nair Vinod Kothari Company Kolkata: New Delhi: Mumbai: 1006-1009, Krishna A-467, First Floor, 403-406, Shreyas Chambers 224 AJC Bose Road Defence Colony, 175, D N Road, Fort Kolkata – 700 017 New Delhi-110024 Mumbai Phone: 033 2281 3742/7715 Phone: 011 41315340 Phone: 022 2261 4021/ 6237 0959 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Website: www.vinodkothari.com 1 Copyright & Disclaimer . This presentation is only for academic purposes; this is not intended to be a professional advice or opinion. Anyone relying on this does so at one’s own discretion. Please do consult your professional consultant for any matter covered by this presentation. The contents of the presentation are intended solely for the use of the client to whom the same is marked by us. No circulation, publication, or unauthorised use of the presentation in any form is allowed, except with our prior written permission. No part of this presentation is intended to be solicitation of professional assignment. 2 About Us Vinod Kothari and Company, company secretaries, is a firm with over 30 years of vintage Based out of Kolkata, New Delhi & Mumbai We are a team of qualified company secretaries, chartered accountants, lawyers and managers. Our Organization’s Credo: Focus on capabilities; opportunities follow 3 Law & Practice relating to Corporate Bonds & Debentures 4 The book can be ordered by clicking here Outline . Introduction to Debentures . State of Indian Bond Market . Comparison of debentures with other forms of borrowings/securities . Types of Debentures . Modes of Issuance & Regulatory Framework . -

Interest-Rate-Growth Differentials and Government Debt Dynamics

From: OECD Journal: Economic Studies Access the journal at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/19952856 Interest-rate-growth differentials and government debt dynamics David Turner, Francesca Spinelli Please cite this article as: Turner, David and Francesca Spinelli (2012), “Interest-rate-growth differentials and government debt dynamics”, OECD Journal: Economic Studies, Vol. 2012/1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eco_studies-2012-5k912k0zkhf8 This document and any map included herein are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. OECD Journal: Economic Studies Volume 2012 © OECD 2013 Interest-rate-growth differentials and government debt dynamics by David Turner and Francesca Spinelli* The differential between the interest rate paid to service government debt and the growth rate of the economy is a key concept in assessing fiscal sustainability. Among OECD economies, this differential was unusually low for much of the last decade compared with the 1980s and the first half of the 1990s. This article investigates the reasons behind this profile using panel estimation on selected OECD economies as means of providing some guidance as to its future development. The results suggest that the fall is partly explained by lower inflation volatility associated with the adoption of monetary policy regimes credibly targeting low inflation, which might be expected to continue. However, the low differential is also partly explained by factors which are likely to be reversed in the future, including very low policy rates, the “global savings glut” and the effect which the European Monetary Union had in reducing long-term interest differentials in the pre-crisis period. -

Sample Debt Validation Letter (Send Via Certified Mail, Return Receipt Requested)

Sample Debt Validation Letter (Send via certified mail, return receipt requested) Date: Your Name Your Address Your City, State, Zip Collection Agency Name Collection Agency Address Collection Agency City, State, Zip RE: Account # (Fill in Account Number) To Whom It May Concern: Be advised this is not a refusal to pay, but a notice that your claim is disputed and validation is requested. Under the Fair Debt collection Practices Act (FDCPA), I have the right to request validation of the debt you say I owe you. I am requesting proof that I am indeed the party you are asking to pay this debt, and there is some contractual obligation that is binding on me to pay this debt. This is NOT a request for “verification” or proof of my mailing address, but a request for VALIDATION made pursuant to 15 USC 1692g Sec. 809 (b) of the FDCPA. I respectfully request that your offices provide me with competent evidence that I have any legal obligation to pay you. At this time I will also inform you that if your offices have or continue to report invalidated information to any of the three major credit bureaus (Equifax, Experian, Trans Union), this action might constitute fraud under both federal and state laws. Due to this fact, if any negative mark is found or continues to report on any of my credit reports by your company or the company you represent, I will not hesitate in bringing legal action against you and your client for the following: Violation of the Fair Debt Collection Practices Act and Defamation of Character. -

Nber Working Papers Series

NBER WORKING PAPERS SERIES WAS THERE A BUBBLE IN THE 1929 STOCK MARKET? Peter Rappoport Eugene N. White Working Paper No. 3612 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 February 1991 We have benefitted from comments made on earlier drafts of this paper by seminar participants at the NEER Summer Institute and Rutgers University. We are particularly indebted to Charles Calomiris, Barry Eicherigreen, Gikas Hardouvelis and Frederic Mishkiri for their suggestions. This paper is part of NBER's research program in Financial Markets and Monetary Economics. Any opinions expressed are those of the authors and not those of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER Working Paper #3612 February 1991 WAS THERE A BUBBLE IN THE 1929 STOCK MARKET? ABSTRACT Standard tests find that no bubbles are present in the stock price data for the last one hundred years. In contrast., historical accounts, focusing on briefer periods, point to the stock market of 1928-1929 as a classic example of a bubble. While previous studies have restricted their attention to the joint behavior of stock prices and dividends over the course of a century, this paper uses the behavior of the premia demanded on loans collateralized by the purchase of stocks to evaluate the claim that the boom and crash of 1929 represented a bubble. We develop a model that permits us to extract an estimate of the path of the bubble and its probability of bursting in any period and demonstrate that the premium behaves as would be expected in the presence of a bubble in stock prices. -

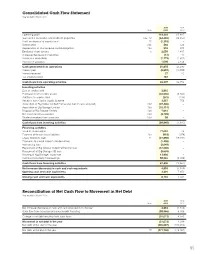

Reconciliation of Net Cash Flow to Movement in Net Debt Year Ended 31 March 2015

Consolidated Cash Flow Statement Year ended 31 March 2015 2015 2014 Note £000 £000 Operating profit 114,203 67,887 Gain on the revaluation of investment properties 13a, 14 (64,465) (28,350) Profit on disposal of surplus land 15 (1,318) – Depreciation 13b 566 526 Depreciation of finance lease capital obligations 13a 918 974 Employee share options 6 2,059 1,437 (Increase)/decrease in inventories (14) 10 Increase in receivables (1,172) (1,652) Increase in payables 1,098 2,458 Cash generated from operations 51,875 43,290 Interest paid (9,692) (10,558) Interest received 27 20 Tax credit received 187 – Cash flows from operating activities 42,397 32,752 Investing activities Sale of surplus land 2,815 – Purchase of non-current assets (42,555) (8,460) Additions to surplus land (231) (136) Receipts from Capital Goods Scheme 3,557 756 Acquisition of Big Yellow Limited Partnership (net of cash acquired) 13d (37,406) – Acquisition of Big Storage Limited 13a (15,114) – Disposal of Big Storage Limited 13a 7,614 – Net investment in associates 13d (3,709) – Dividend received from associate 13d 89 – Cash flows from investing activities (84,940) (7,840) Financing activities Issue of share capital 77,094 42 Payment of finance lease liabilities 13a (918) (974) Equity dividends paid 11 (27,890) (19,591) Payments to cancel interest rate derivatives (1,408) – Refinancing fees (2,649) – Repayment of Big Yellow Limited Partnership loan (57,000) – Repayment of Big Storage AIB loan (9,659) – Drawing of Big Storage Lloyds loan 13,900 – Increase/(reduction) in borrowings -

February 9, 2020 Falling Real Interest Rates, Rising Debt: a Free Lunch?

February 9, 2020 Falling Real Interest Rates, Rising Debt: A Free Lunch? By Kenneth Rogoff, Harvard University1 1 An earlier version of this paper was presented at the American Economic Association January 3 2020 meeting in San Diego in a session entitled “The United States Economy: Growth, Stagnation or New Financial Crisis?” chaired by Dominick Salvatore. The author is grateful to Molly and Dominic Ferrante Fund at Harvard University for research support. 1 With real interest rates hovering near multi-decade lows, and even below today’s slow growth rates, has higher government debt become a proverbial free lunch in many advanced countries?2 It is certainly true that low borrowing rates help justify greater government spending on high social return investment and education projects, and should make governments more relaxed about countercyclical fiscal policy, the “free lunch” perspective is an illusion that ignores most governments’ massive off-balance-sheet obligations, as well the possibility that borrowing rates could rise in a future economic crisis, even if they fell in the last one. As Lawrence Kotlikoff (2019) has long emphasized (see also Auerbach, Gokhale and Kotlikoff, 1992) 3 standard measures of government in debt have in some sense become an accounting fiction in the modern post World War II welfare state. Every advanced economy government today spends more on publicly provided old age support and pensions alone than on interest payment, and would still be doing so even if real interest rates on government debt were two percent higher. And that does not take account of other social insurance programs, most notably old-age medical care. -

Debt Collection Guide Update

Debt Collection Guide Update This Update includes new information you should know when dealing with debt collectors. 1. In New York, a debt collector cannot collect or attempt to collect on a payday loan. Payday loans are illegal in New York. A payday loan is a high-interest loan borrowed against your next paycheck. To apply for a payday loan, you need to have a checking account and proof of income. In New York State, most payday loans are handled by phone or online. If a collection agency tries to collect on a payday loan, visit nyc.gov/dca or contact 311 to file a complaint with DCA. 2. Beware of debt collection companies or companies working with debt collection companies that offer you a credit card if you repay, in part or in full, an old debt that may have expired. Companies may use terms like “Fresh Start Program” or “Balance Transfer Program” to describe offers to transfer your old debt to a new credit card account after you make a certain number of payments. If you accept the credit card offer and start making pay- ments, the debt collection agency’s time limit (statute of limitations) for suing you to collect this debt will restart. The company offering the credit card may not tell you that this is a consequence of getting the credit card. See the section What Should You Do When a Debt Collection Agency Contacts You? for information about statute of limitations. 3. It is illegal for a debt collection agency to use “caller ID spoofing.” Some debt collection agencies are using spoofed (or faked) phone numbers to disguise their identities on caller ID. -

A Roadmap to the Preparation of the Statement of Cash Flows

A Roadmap to the Preparation of the Statement of Cash Flows May 2020 The FASB Accounting Standards Codification® material is copyrighted by the Financial Accounting Foundation, 401 Merritt 7, PO Box 5116, Norwalk, CT 06856-5116, and is reproduced with permission. This publication contains general information only and Deloitte is not, by means of this publication, rendering accounting, business, financial, investment, legal, tax, or other professional advice or services. This publication is not a substitute for such professional advice or services, nor should it be used as a basis for any decision or action that may affect your business. Before making any decision or taking any action that may affect your business, you should consult a qualified professional advisor. Deloitte shall not be responsible for any loss sustained by any person who relies on this publication. The services described herein are illustrative in nature and are intended to demonstrate our experience and capabilities in these areas; however, due to independence restrictions that may apply to audit clients (including affiliates) of Deloitte & Touche LLP, we may be unable to provide certain services based on individual facts and circumstances. As used in this document, “Deloitte” means Deloitte & Touche LLP, Deloitte Consulting LLP, Deloitte Tax LLP, and Deloitte Financial Advisory Services LLP, which are separate subsidiaries of Deloitte LLP. Please see www.deloitte.com/us/about for a detailed description of our legal structure. Copyright © 2020 Deloitte Development LLC. All rights reserved. Publications in Deloitte’s Roadmap Series Business Combinations Business Combinations — SEC Reporting Considerations Carve-Out Transactions Comparing IFRS Standards and U.S. -

Convertible Debentures – a Primer

Portfolio Advisory Group May 12, 2011 Convertible Debentures – A Primer A convertible debenture is a hybrid financial instrument Convertible debentures offer some advantages over that has both fixed income and equity characteristics. In investing in common equity. As holders of a more its simplest terms, it is a bond that gives the holder the senior security, investors have a greater claim on the option to convert into an underlying equity instrument at firm’s assets in the event of insolvency. Secondly, the a predetermined price. Thus, investors receive a regular investor’s income flow is more stable since coupon income flow through the coupon payments plus the payments are a contractual obligation. Finally, ability to participate in capital appreciation through the convertible bonds offer both a measure of protection potential conversion to equity. Convertible debentures in bear markets through the regular bond features and are usually subordinated to the company’s other debt. participation in capital appreciation in bull markets through the conversion option. Unlike traditional Convertible debentures are issued by companies as a bonds, convertible debentures trade on a stock means of deferred equity financing in the belief that exchange but generally have a small issue size which the present share price is too low for issuing common can result in limited liquidity. shares. These securities offer a conversion into the underlying issuer’s shares at prices above the current VALUATION level (referred to as the conversion premium). In A convertible bond can be thought of as a straight return for offering an equity option, firms realize both bond with a call option for the underlying equity interest savings, since coupons on convertible bonds security. -

Debt and the Retirement Savings Equation

A WORKING PAPER Debt and the Retirement Savings Equation By Zhikun Liu, Ph.D., CFP® and David M. Blanchett, Ph.D., CFA, CFP® SEPTEMBER 2019 Debt and the Retirement Savings Equation Financial firms and advisors have historically spent more time focusing on the asset side of the household balance sheet than the liability side. However, this focus has recently begun to shift, as the industry has begun using the lens of financial wellness to assess individuals’ overall financial well-being, including liabilities such as student loan debt. As a result, financial professionals need to consider their clients’ financial health within the context of households’ entire balance sheets, taking both assets and liabilities into consideration. The debt levels of American households have increased significantly since the 2007-2009 economic recession.1 As of December 31, 2018, total U.S. household indebtedness was approximately $13.5 trillion according to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. This figure is higher than the previous peak of $12.7 trillion in the third quarter of 2008 (adjusted to 2018 dollars) and is an increase of 21.4% compared with the second quarter of 2013.2 These high debt levels have created significant challenges for average American households. Data from the 2016 Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF) suggest that American households with net worths under $1 million spend more in total interest payments on debts than they can expect to gain from their financial assets.3 Therefore, spending time on “debt optimization” is likely to result in better outcomes than focusing on assets alone. 1 Bricker, Jesse, Lisa J. -

CFPB Consumer Laws and Regulations FDCPA

CFPB Consumer Laws and Regulations FDCPA Fair Debt Collection Practices Act1 The Fair Debt Collection Practices Act (FDCPA)(15 U.S.C. 1692 et seq.), which became effective March 20, 1978, was designed to eliminate abusive, deceptive, and unfair debt collection practices. In addition, the federal law (15 U.S.C. 1692 et seq.) protects reputable debt collectors from unfair competition and encourages consistent state action to protect consumers from abuses in debt collection. The Dodd-Frank Act granted rulemaking authority under the FDCPA to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB)2 and, with respect to entities under its jurisdiction, granted authority to the CFPB to supervise for and enforce compliance with the FDCPA.3 Debt That Is Covered The FDCPA applies only to the collection of debt incurred by a consumer primarily for personal, family, or household purposes. It does not apply to the collection of corporate debt or to debt owed for business or agricultural purposes. Debt Collectors That Are Covered Under FDCPA, a “debt collector” is defined as any person who regularly collects, or attempts to collect, consumer debts for another person or institution or uses some name other than its own when collecting its own consumer debts. That definition would include, for example, an institution that regularly collects debts for an unrelated institution. This includes reciprocal service arrangements where one institution solicits the help of another in collecting a defaulted debt from a customer who has moved. Debt Collectors That Are Not Covered An institution is not a debt collector under the FDCPA when it collects: • Another’s debts in isolated instances. -

Household Debt and Credit, 2019

CENTER FOR MICROECONOMIC DATA WWW.NEWYORKFED.ORG/MICROECONOMICS QUA RTERL Y REPORT ON HOUSEHOLD DEBT AND CREDIT 20 19:Q4 (RELEASED FEBRUARY 2020) FEDERAL RESERVE BANK of NEW YORK RESEARCH AND STATISTICS GROUP ANALYSIS BASED ON NEW YORK FED CONSUMER CREDIT PANEL/EQUIFAX DATA Household Debt and Credit Developments in 2019Q41 Aggregate household debt balances increased by $193 billion in the fourth quarter of 2019, a 1.4% increase, and now stand at $14.15 trillion. Balances have been steadily rising for five years and in aggregate are now $1.5 trillion higher, in nominal terms, than the previous peak (2008Q3) peak of $12.68 trillion. Overall household debt is now 26.8% above the 2013Q2 trough. Mortgage balances shown on consumer credit reports on December 31 stood at $9.56 trillion, a $120 billion increase from 2019Q3. Balances on home equity lines of credit (HELOC) saw a $6 billion decline, bringing the outstanding balance to $390 billion and continuing the 10 year downward trend. Non-housing balances increased by $79 billion in the fourth quarter, with increases across the board, including $16 billion in auto loans, $46 billion in credit card balances, and $10 billion in student loans. Note that the large increase in credit card balances reflects, in part, a shifting of balances across debt types as portfolios have shifted among lenders. New extensions of credit were strong in the fourth quarter. Auto loan originations, which include both newly opened loans and leases, at $159 billion, were about flat with the previous quarter’s high level. Mortgage originations, which we measure as appearances of new mortgage balances on consumer credit reports and which include refinances, were at $752 billion, a large increase from the $528 billion in the third quarter and the highest volume in originations since the end of 2005.