University of Latvia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Health Systems in Transition

61575 Latvia HiT_2_WEB.pdf 1 03/03/2020 09:55 Vol. 21 No. 4 2019 Vol. Health Systems in Transition Vol. 21 No. 4 2019 Health Systems in Transition: in Transition: Health Systems C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Latvia Latvia Health system review Daiga Behmane Alina Dudele Anita Villerusa Janis Misins The Observatory is a partnership, hosted by WHO/Europe, which includes other international organizations (the European Commission, the World Bank); national and regional governments (Austria, Belgium, Finland, Kristine Klavina Ireland, Norway, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the Veneto Region of Italy); other health system organizations (the French National Union of Health Insurance Funds (UNCAM), the Dzintars Mozgis Health Foundation); and academia (the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) and the Giada Scarpetti London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM)). The Observatory has a secretariat in Brussels and it has hubs in London at LSE and LSHTM) and at the Berlin University of Technology. HiTs are in-depth profiles of health systems and policies, produced using a standardized approach that allows comparison across countries. They provide facts, figures and analysis and highlight reform initiatives in progress. Print ISSN 1817-6119 Web ISSN 1817-6127 61575 Latvia HiT_2_WEB.pdf 2 03/03/2020 09:55 Giada Scarpetti (Editor), and Ewout van Ginneken (Series editor) were responsible for this HiT Editorial Board Series editors Reinhard Busse, Berlin University of Technology, Germany Josep Figueras, European -

Karlis Ulmanis: from University of Nebraska Graduate to President of Latvia

Nebraska History posts materials online for your personal use. Please remember that the contents of Nebraska History are copyrighted by the Nebraska State Historical Society (except for materials credited to other institutions). The NSHS retains its copyrights even to materials it posts on the web. For permission to re-use materials or for photo ordering information, please see: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/magazine/permission.htm Nebraska State Historical Society members receive four issues of Nebraska History and four issues of Nebraska History News annually. For membership information, see: http://nebraskahistory.org/admin/members/index.htm Article Title: Karlis Ulmanis: From University of Nebraska Graduate to President of Latvia Full Citation: Lawrence E Murphy, Aivars G Ronis, and Arijs R Liepins, “Karlis Ulmanis: From University of Nebraska Graduate to President of Latvia,” Nebraska History 80 (1999): 46-54 URL of article: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/publish/publicat/history/full-text/NH1999Ulmanis.pdf Date: 11/30/2012 Article Summary: Karlis Ulmanis studied and then taught briefly at the University of Nebraska as a Latvian refugee. As president of Latvia years later, he shared his enthusiasm for Nebraska traditions with citizens of his country. Cataloging Information: Names: Karlis Augusts Ulmanis, Howard R Smith, Jerome Warner, Charles J Warner, Karl Kleege (orininally Kliegis), Theodore Kleege, Herman Kleege, Val Kuska, Howard J Gramlich, Vere Culver, Harry B Coffee, J Gordon Roberts, A L Haecker, Hermanis Endzelins, Guntis -

VAP 25 Riga Report 2001

THE UNIVERSITIES PROJECT OF THE SALZBURG SEMINAR VISITING ADVISORS' REPORT UNIVERSITY OF LATVIA RIGA, LATVIA APRIL 23-27, 2001 Team Members Dr. John W. Ryan (team leader), Chancellor Emeritus, State University of New York Dr. Achim Mehlhorn, Rector, Technical University of Dresden Dr. Janina Jozwiak, former Rector, Warsaw School of Economics Ms. Martha Gecek, Coordinator, Visiting Advisors Program, Salzburg Seminar; Administrative Director, American Studies Center University of Latvia Team Members Dr. Ivars Lacis, Rector Dr. Juris Krumins, Vice Rector for Studies Dr. Indrikis Muiznieks, Vice Rector for Research Mr. Pavels Fricbergs, Chancellor Mr. Atis Peics, Director Mr. Janis Stonis, Administrative Director Dr. Dace Gertnere, Head, Department of Research Ms. Alina Grzhibovska, Head, Department of International Relations Dr. Lolita Spruge, Head, Department of Studies The University of Latvia is the only classical university in Latvia, thus the main center for higher education, research, and culture for the humanities, natural sciences, and social sciences. It was founded in 1919, building upon the Riga Polytechnic (founded in 1862) and currently comprises thirteen faculties and more than thirty research institutions, some having independent status, several museums, and other academic and cultural facilities. The University enrolls nearly 34,000 students (2000), more than two-thirds in undergraduate study. The academic staff numbers just over 800 engaged in teaching and research. The members of the Team of Advisors appreciate the privilege of visiting the University of Latvia, and are grateful to Rector Ivars Lacis and his colleagues for their extraordinary candor in our discussions, and their exceptional hospitality. 1 VAP Report——Riga, Latvia, April, 2001 The Advisors commend the Rector for the comprehensive preparation for the visit. -

Revista Romană De Geografie Politică

Revista Română de Geografie Politică Year XXIII, no. 1, June 2021, pp. 1-57 ISSN 1582-7763, E-ISSN 2065-1619 http://rrgp.uoradea.ro, [email protected] REVISTA ROMÂNĂ DE GEOGRAFIE POLITICĂ Romanian Review on Political Geography Year XXIII, no. 1, June 2021 Editor-in-Chief: Alexandru ILIEŞ, University of Oradea, Romania Associate Editors: Voicu BODOCAN, “Babeş-Bolyai” University of Cluj-Napoca, Romania Milan BUFON, "Primorska” University of Koper, Slovenia Jan WENDT, University of Gdansk, Poland Vasile GRAMA, University of Oradea, Romania Scientific Committee: Silviu COSTACHIE, University of Bucharest, Romania Remus CREŢAN, West University of Timişoara, Romania Olivier DEHOORNE, University of the French Antilles and Guyana, France Anton GOSAR, “Primorska” University of Koper, Slovenia Ioan HORGA, University of Oradea, Romania Ioan IANOŞ, University of Bucharest, Romania Corneliu IAŢU, “Al. I. Cuza” University of Iaşi, Romania Vladimir KOLOSSOV, Russian Academy of Science, Russia Ionel MUNTELE, “Al. I. Cuza” University of Iaşi, Romania Silviu NEGUŢ, Academy of Economical Studies of Bucharest, Romania John O’LOUGHLIN, University of Colorado at Boulder, U.S.A. Lia POP, University of Oradea, Romania Nicolae POPA, West University of Timişoara, Romania Stéphane ROSIÈRE, University of Reims Champagne-Ardenne, France Andre-Louis SANGUIN, University of Paris-Sorbonne, France Radu SĂGEATĂ, Romanian Academy, Institute of Geography, Romania Marcin Wojciech SOLARZ, University of Warsaw, Poland Alexandru UNGUREANU, Romanian Academy Member, “Al. I. Cuza” University of Iaşi, Romania Luca ZARRILLI, “G. D’Annunzio” University, Chieti-Pescara, Italy Technical Editor: Grigore HERMAN, University of Oradea, Romania Foreign Language Supervisor: Corina TĂTAR, University of Oradea, Romania The content of the published material falls under the authors’ responsibility exclusively. -

UNIVERSITY of PRISHTINA the University-History

Welcome to the Republic of Kosova UNIVERSITY OF PRISHTINA The University-History • The University of Prishtina was founded by the Law on the Foundation of the University of Prishtina, which was passed by the Assembly of the Socialist Province of Kosova on 18 November 1969. • The foundation of the University of Prishtina was a historical event for Kosova’s population, and especially for the Albanian nation. The Foundation Assembly of the University of Prishtina was held on 13 February 1970. • Two days later, on 15 February 1970 the Ceremonial Meeting of the Assembly was held in which the 15 February was proclaimed The Day of the University of Prishtina. • The University of Prishtina (UP), similar to other universities in the world, conveys unique responsibilities in professional training and research guidance, which are determinant for the development of the industry and trade, infra-structure, and society. • UP has started in 2001 the reforming of all academic levels in accordance with the Bologna Declaration, aiming the integration into the European Higher Education System. Facts and Figures 17 Faculties Bachelor studies – 38533 students Master studies – 10047 students PhD studies – 152 students ____________________________ Total number of students: 48732 Total number of academic staff: 1021 Visiting professors: 885 Total number of teaching assistants: 396 Administrative staff: 399 Goals • Internationalization • Integration of Kosova HE in EU • Harmonization of study programmes of the Bologna Process • Full implementation of ECTS • Participation -

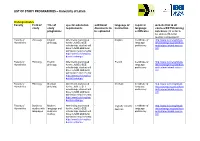

University of Latvia

LIST OF STUDY PROGRAMMES – University of Latvia Undergraduates Faculty Field of Title of special admission additional language of required website link to all study study requirements documents to instruction language courses/ECTS/learning programme be uploaded certificates outcomes (in order to be able to fill in the learning agreement) Faculty of Philology English After being nominated - English Certificate of http://www.lu.lv/eng/istude Humanities philology for the JoinEU-SEE language nts/exchange/courses/hum scholarship, student will proficiency anities/provisional-course- have to fulfill additional list/ admission requirements: http://www.lu.lv/eng/istu dents/exchange/ Faculty of Philology French After being nominated - French Certificate of http://www.lu.lv/eng/istude Humanities philology for the JoinEU-SEE language nts/exchange/courses/hum scholarship, student will proficiency anities/provisional-course- have to fulfill additional list/ admission requirements: http://www.lu.lv/eng/istu dents/exchange/ Faculty of Philology German After being nominated - German Certificate of http://www.lu.lv/eng/istude Humanities philology for the JoinEU-SEE language nts/exchange/courses/hum scholarship, student will proficiency anities/provisional-course- have to fulfill additional list/ admission requirements: http://www.lu.lv/eng/istu dents/exchange/ Faculty of Business Modern After being nominated - English/ French/ Certificate of http://www.lu.lv/eng/istude Humanities studies with language and for the JoinEU-SEE German language nts/exchange/courses/hum -

University of Latvia

UNIVERSITY OF LATVIA International Programmes 1 Rector’s Welcome On the verge of one hundred Established in 1919, the expand as new study infrastructure University of Latvia, the only classical will be built (Academic Centre for Social university in Latvia, has been a national Sciences and Humanities) as well as centre of higher education for almost facilities for scientific research and a century. Today it is a place where the technology transfer in the fields of life brightest academic minds, innovative science and nanotechnology. research and exciting study process meet. We are certain that the world class study and research process, the University of Latvia is increasing number of international continuously developing — expanding students and dynamic student life horizons of the academic work and enhanced by the outstanding beauty scientific research by collaborating of local environment and Riga city will internationally, increasing the number make your studies or research at the of international study programmes, University of Latvia an unforgettable strengthening its cooperation with experience and a great contribution to industrial partners. The newly built your future. Academic Centre for Natural Sciences has become an excellent environment Experience the University of Latvia! for research-based study process and multidisciplinary research opportunities. And this is only a Prof. Indriķis Muižnieks beginning. Within the years to come, Rector of the University of Latvia the University of Latvia campus will Full Member of the Latvian -

Dr. Janis Priede University of Latvia Faculty of Economics and Management

Dr. Janis Priede University of Latvia Faculty of Economics and Management Pursuing the Fulbright Research Project entitled "International Trade and Competitiveness of Latvia and Other European Union Countries" At Columbia Consortium for Risk Management under Professor Graciela Chichilnisky for the period of: January 2014 through June 2014. A redacted version of Dr. Pried’s academic resume follows herein. Dr.oec. Janis Priede Assistant Professor Curriculum Vitae Contact information Address Telephone E-mail [email protected] Education Dates 2006 – 2010 Title of qualification awarded Doctor of Economics Name and type of University of Latvia, Faculty of Economics and Management, 5 Aspazijas organisation providing blvd., Riga, Latvia education and training Dates 2004 – 2006 Title of qualification awarded Master of Social Sciences in Economics (with honors) Name and type of University of Latvia, Faculty of Economics and Management, 5 Aspazijas organisation providing blvd., Riga, Latvia education and training Dates 2000 – 2004 Title of qualification awarded Bachelor of Social Sciences in Economics (with University Rector Award for undergraduate work) Name and type of University of Latvia, Faculty of Economics and Management, 5 Aspazijas organisation providing blvd., Riga, Latvia education and training Work experience Dates 2012 - until now Occupation or position held Assistant Professor Name and address of University of Latvia, Faculty of Economics and Management, 5 Aspazijas employer blvd., Riga, Latvia Dates 2009 - until now Occupation or -

Baltic Languages and White Nights Contacts Between Baltic and Uralic Languages

Baltic Languages and White Nights Contacts between Baltic and Uralic languages International Conference University of Helsinki, 11–12 June 2012 Programme Abstracts Participants Conference Programme Monday 11 June Registration 9.30 – 10.00. Metsätalo - Forsthuset, Unioninkatu - Unionsgatan 40, III Floor. Plenary session 10.00 – 17.00, Room 8, III Floor. Moderated by Santeri Junttila and Laimute Balode. 10:00 Arto Mustajoki, University of Helsinki. Opening of the conference. 10:15 Santeri Junttila, University of Helsinki: The contacts between Proto-Finnic and Baltic: do we know anything Thomsen did not? 10:45 Riho Grünthal, University of Helsinki: Livonian at the cross-roads of language contacts 11:15 Anna Daugaviete, Saint Petersburg State University: The development of unstressed syllables in Latvian: Lithuanian and Baltic-Finnic parallels 11:45 Tea and coffee 12:00 Karl Pajusalu, University of Helsinki: On phonology of the Salaca Livonian language 12:30 Laimute Balode, University of Helsinki/ University of Latvia: Criteria for determining of possible Finno-Ugrisms in Latvian toponymy 13:00 Lunch 14:30 Pauls Balodis, Latvian Language Institute: Surnames of Finno-Ugric origin in Latvia 15:00 PƝteris Vanags, Stockholm University/ University of Latvia: Latvian and Estonian names for traditional feast days of the Christian church: Common history and sources 15:30 Tea and coffee 16:00 Adam Hyllested, University of Copenhagen: The origins of Finnish aika 'time' and aita 'fence': Germanic, Baltic, or Slavic? 16:30 Janne Saarikivi, University of Helsinki: On the stratigraphy of borrowings in Finnic. Reconsidering the Slavic and Baltic borrowings. 17.30–19.30 Reception at the Embassy of the Republic of Lithuania, Rauhankatu - Fredsgatan 13 A Tuesday 12 June Section I. -

Governance and Adaptation to Innovative Modes of Higher Education Provision

EUROPE Governance and Adaptation to Innovative Modes of Higher Education Provision Cecile Hoareau McGrath, Joanna Hofman, Lubica Bajziková, Emma Harte, Anna Lasakova, Paulina Pankowska, S. Sasso, Julie Belanger, S. Florea, J. Krivogra Prepared for The European Commission Project number 539628-LLP-1-2013-NL-ERASMUS-EIGF Governance and Adaptation to Innovative Modes of Higher Education Provision (GAIHE) Project information Project acronym: GAIHE Project title: Governance and Adaptation to Innovative Modes of Higher Education Provision Project number: 539628-LLP-1-2013-NL-ERASMUS-EIGF Sub-programme or KA: Lifelong Learning Programme Project website: http://www.he-governance-of- innovation.esen.education.fr/ Reporting period: From 01/10/2013 To 31/06/2016 Report version: 1 Date of preparation: 2015–2016 Beneficiary organisation: Maastricht University, School of Governance École Normale Supérieure de Lyon Dublin Institute of Technology University of Latvia Lucian Blaga University of Sibiu Comenius University in Bratislava University of Ss. Cyrill and Methodius, Trnava University of Maribor University of Salamanca, ECYT Institute University of Alicante 539628-LLP-1-2013-NL-ERASMUS-EIGF 2 / 217 Governance and Adaptation to Innovative Modes of Higher Education Provision (GAIHE) University of Strasbourg RAND Europe Project coordinators: Dr Cecile McGrath & Joanna Hofman Project coordinator organisation: RAND Europe Project coordinator telephone number: + 44 1223 273 850 Project coordinator email address: [email protected] [email protected] 539628-LLP-1-2013-NL-ERASMUS-EIGF 3 / 217 Governance and Adaptation to Innovative Modes of Higher Education Provision (GAIHE) This project has been funded with support from the European Commission. This publication reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. -

Global Partners —

EXCHANGE PROGRAM Global DESTINATION GROUPS Group A: USA/ASIA/CANADA Group B: EUROPE/UK/LATIN AMERICA partners Group U: UTRECHT NETWORK CONTACT US — Office of Global Student Mobility STUDENTS MUST CHOOSE THREE PREFERENCES FROM ONE GROUP ONLY. Student Central (Builing 17) W: uow.info/study-overseas GROUP B AND GROUP U HAVE THE SAME APPLICATION DEADLINE. E: [email protected] P: +61 2 4221 5400 INSTITUTION GROUP INSTITUTION GROUP INSTITUTION GROUP AUSTRIA CZECH REPUBLIC HONG KONG University of Graz Masaryk University City University of Hong Kong Hong Kong Baptist University DENMARK BELGIUM The Education University of Aarhus University Hong Kong University of Antwerp University of Copenhagen The Hong Kong Polytechnic KU Leuven University of Southern University BRAZIL Denmark UOW College Hong Kong Federal University of Santa ESTONIA HUNGARY Catarina University of Tartu Eötvös Loránd University (ELTE) Pontifical Catholic University of Campinas FINLAND ICELAND Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro University of Eastern Finland University of Iceland University of São Paulo FRANCE INDIA CANADA Audencia Business School Birla Institute of Management Technology (BIMTECH) Concordia University ESSCA School of Management IFIM Business School HEC Montreal Institut Polytechnique LaSalle Manipal Academy of Higher McMaster University Beauvais Education University of Alberta Lille Catholic University (IÉSEG School of Management) O.P. Jindal Global University University of British Columbia National Institute of Applied University of Calgary -

UNIVERSITY of LATVIA Erasmus Code LV RIGA01 Address: Raina Blvd

International Relations Department Raina Boulevard 19 Riga, LV-1586 Latvia Key data sheet UNIVERSITY OF LATVIA Erasmus code LV RIGA01 Address: Raina Blvd. 19, Riga, LV-1586, Latvia WWW www.lu.lv/eng/ Rector Prof. Mārcis AUZIŅŠ INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS OFFICE Director, Erasmus Mrs. Alina GRŽIBOVSKA Institutional Coordinator Address: Raina Blvd. 19, Riga, LV-1586, Latvia Phone: + 371 67034334 Fax: + 371 67243091 E-mail: [email protected] Contact person for Mrs. Natālija IVANOVA outgoing students Phone: + 371 67034335 Fax: + 371 67243091 E-mail: [email protected] Contact person for Ms. Beāte RAMIŅA incoming students Phone: + 371 67034350 Fax: + 371 67243091 E-mail: [email protected] Contact person for Ms. Sarmīte RUTKOVSKA Erasmus Mundus program Phone: + 371 67034336 Fax: + 371 67243091 E-mail: [email protected] Contact person for Ms. Zane SVILĀNE Bilateral Agreements Phone: + 371 37034337 Fax: + 371 67243091 E-mail: [email protected] INFORMATION FOR INTERNATIONAL STUDENTS Autumn semester: - registration week: 25.08.14 – 31.08.14 - studies: 01.09.14 – 21.12.14 Academic calendar 2014/2015: - individual studies and exams: 05.01.15 – 01.02.15 http://www.lu.lv/eng/istudents/ exchange/calendar/ Spring semester: - registration week: 02.02.15 – 08.02.15 - studies: 09.02.15 – 06.06.15 - individual studies and exams: 07.06.15 – 04.07.15 Application deadlines Autumn: -May 15th Spring: -November 15th Nomination deadlines (by e-mail [email protected] ) Autumn semester: -April 15th Spring: -October 15th Language of instructions The official language of instruction is Latvian. Courses for international students are offered in English Application information for http://www.lu.lv/eng/istudents/exchange/ incoming students: Accommodation information: http://www.lu.lv/eng/services/accommodation/ Courses for incoming students: http://www.lu.lv/eng/istudents/exchange/courses/ General and Practical http://www.lu.lv/eng/istudents/exchange/advice/ information for incomings: INTERNATIONAL COORDINATORS AT FACULTIES FACULTY OF BIOLOGY Departmental Coordinator Assoc.