Geographies of Artificial Lighting in Everyday Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Whitings Way London Industrial Park • Beckton • E6 6Lr

UNIT 1A WHITINGS WAY LONDON INDUSTRIAL PARK • BECKTON • E6 6LR INDUSTRIAL/WAREHOUSE UNIT TO BE REFURBISHED 17,528 sq ft (1,629 sq m) approx. STEEL PORTAL TO LET FRAME MINIMUM EAVES HEIGHT 8.8 METRES 2 LEVEL ACCESS LOADING DOORS REFURBISHED OFFICES DIRECT ACCESS TO CENTRAL LONDON VIA THE A13 SECURE YARD AREA UNIT 1A • WHITINGS WAY • LONDON INDUSTRIAL PARK • BECKTON • E6 6LR Canary Wharf SITUATION O2 Arena City of London Excel London City Airport A13 Beckton DLR Station Beckton Retail Park A13 Wo olwich Manor Way Whitings Way A406 & M25 UNIT 1A • WHITINGS WAY • LONDON INDUSTRIAL PARK • BECKTON • E6 6LR THE PROPERTY The property is situated at the corner of Whitings Way and Eastbury Road and comprises an end of terrace, steel portal frame industrial / warehouse unit, with ancillary office accommodation on 1st and 2nd floors. The property is to be fully refurbished throughout. • Brick and profile steel elevations • LED lighting in warehouse • Excellent internal eaves height of 8.8m • Fenced yard providing loading and parking approached directly off Whitings Way • Second loading door situated on Eastbury Road • Refurbished offices with air conditioning. Accommodation sq ft Warehouse 13,609 Office 1st Floor 735 Office 2nd Floor 3,184 Total GIA 17,528 UNIT 1A • WHITINGS WAY • LONDON INDUSTRIAL PARK • BECKTON • E6 6LR THE PROPERTY UNIT 1A WHITINGS WAY UNIT 1A • WHITINGS WAY • LONDON INDUSTRIAL PARK • BECKTON • E6 6LR N C I R C M11 U TERMS L LOCATION A R R D The unit is available to let on a new full Y WA A117 DS FRE repairing and insuring lease for a term to A406 AL A13 be agreed. -

YPG2EL Newspaper

THE YOUNG PERSON’S GUIDE TO EAST LONDON East London places they don’t put in travel guides! Recipient of a Media Trust Community Voices award A BIG THANK YOU TO OUR SPONSORS This organisation has been awarded a Transformers grant, funded by the National Lottery through the Olympic Lottery Distributor and managed by ELBA Café Verde @ Riverside > The Mosaic, 45 Narrow Street, Limehouse, London E14 8DN > Fresh food, authentic Italian menu, nice surroundings – a good place to hang out, sit with an ice cream and watch the fountain. For the full review and travel information go to page 5. great places to visit in East London reviewed by the EY ETCH FO P UN K D C A JA T I E O H N Discover T B 9 teenagers who live there. In this guide you’ll find reviews, A C 9 K 9 1 I N E G C N YO I U E S travel information and photos of over 200 places to visit, NG PEOPL all within the five London 2012 Olympic boroughs. WWW.YPG2EL.ORG Young Persons Guide to East London 3 About the Project How to use the guide ind an East London that won’t be All sites are listed A-Z order. Each place entry in the travel guides. This guide begins with the areas of interest to which it F will take you to the places most relates: visited by East London teenagers, whether Arts and Culture, Beckton District Park South to eat, shop, play or just hang out. Hanging Out, Parks, clubs, sport, arts and music Great Views, venues, mosques, temples and churches, Sport, Let’s youth centres, markets, places of history Shop, Transport, and heritage are all here. -

Newham Choicehomes Lettings Area Bidding Closes 26 October 2020

Newham ChoiceHomes Lettings Area Bidding closes 26 October 2020 SILVERTOWN Poppy Apartments, 11 Millet Place, E16 CUSTOM HOUSE Tollgate Road, E16 3LA Ref:213848 2YH Ref:213841 Landlord: Grainger Trust Limited Landlord: Newham Type: Flat Bedrooms:1 Type: Flat Bedrooms:1 Bedsizes: 1 double Level: 2nd floor Bedsizes: 1 double Level: 1st floor Other: 0.3 miles to W Silvertown station. Bids accepted Other: Gas Central Heating. 1 mile to Prince Regent DLR from couple/single person & wheelchair user. Station. Suitable for couple/single applicant. Available parking (£130 PCM). AFFORDABLE RENT. RENT (including charges of £10.00) £228.35pw RENT (including charges of £14.84) £112.74pw EAST HAM Melford Road, E6 3QY GREEN STREET Parr Road, E6 1QL Ref:213852 SOUTH Ref:213845 Landlord: Newham Landlord: Newham Type: Flat Bedrooms:1 Type: Flat Bedrooms:1 Bedsizes: 1 double Level: 1st floor Bedsizes: 1 double Level: 3rd floor Other: 0.9 miles to Beckton DLR station. Suitable for Other: Gas Central Heating. 0.6 miles to Upton Park couple/single applicant. Shower with seat - NO Station. Suitable for couple/single applicant. BATH RENT (including charges of £13.47) £101.26pw RENT (including charges of £14.12) £101.90pw MANOR PARK Durban Court, Katherine Road, E7 8PW FOREST GATE Joseph Lister Court, Upton Lane, Forest Ref:213834 Ref:213791 Gate, E7 9PS Landlord: Newham Landlord: L&Q Type: Flat Bedrooms:1 Type: Flat Bedrooms:2 Bedsizes: 1 double Level: 5th floor Bedsizes: 1 double - 1 single Level: 2nd floor Other: Gas Central Heating. 0.5 miles to Upton Park Other: 0.8 Miles to Plaistow Station. -

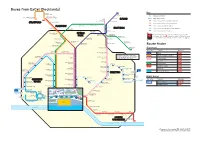

Buses from Gallions Reach DLR Station

BECKTON Buses from Gallions Reach DLR Station Hail & Ride Route finder section 366 Bus route Towards Bus stops Redbridge Redbridge Roding Lane South Falmouth Gardens 101 Gallions Reach BCGX Wanstead DEHW Redbridge 262 East Beckton ABCG Stratford DEFH The Drive 366 Beckton DEHW WANSTEAD Redbridge BCGX Ilford 376 Beckton FX Wanstead East Ham AW 101 Woodbine Place ILFORD Ilford 474 Canning Town BKLX Town Centre Manor Park EIJW Aldersbrook Road Sunnyside Road Night buses City of London Cemetery Bus route Towards Bus stops section Hail & Ride Eton Road N551 Gallions Reach ABCG Manor Park Trafalgar Square DEFH 474 EAST HAM East Ham South Park Drive Other buses Plashet Grove Bus route Towards Bus stops STRATFORD Upton Park East Ham High Street North Loxford Lane 678 School journey Beckton FX Stratford AW 262 Stratford D East Ham Bus Station Newham Town Hall Barking Bus Garage Stratford 376 East Ham High Street South Broadway Upton Park Boleyn Marlow Road BARKING West Ham United F.C. Barking Key East Ham High Street South Mortimer Road 101 Day buses in black Plaistow Barking The yellow tinted area includes every Town Centre N551 Night buses in blue bus stop up to about one-and-a-half Boundary Road East Ham High Street South O Lonsdale Avenue miles from Gallions Reach DLR Station. — Connections with London Underground PLAISTOW Plaistow Main stops are shown in the white Beckton o Connections with London Overground Green Gate Showcase Cinema Woolwich Manor Way area outside. o Connections with TfL Rail Albatross Close Triangle Retail Park R Connections -

Buses from Excel (Docklands)

Buses from ExCel (Docklands) Stratford 147 Key Great Eastern Road Ilford Hainault Street 147 Day buses in black Stratford Bus Station Stratford City for Stratford Bus Station Ilford N551 Night buses in blue 241 300 ILFORD 473 East Ham r- Wordsworth Avenue Connections with London Underground Stratford Broadway Little Ilford Lane STRATFORD o Connections with London Overground Forest Gate Katherine Road Green Street n Connections with National Rail PLAISTOW East Ham Plaistow d Forest Gate EAST HAM Connections with Docklands Light Railway Princess Alice East Ham f Upton Park Newham Town Hall Connections with river boats Boleyn Plaistow High Street UPTON ,aÚ Kennedy Close Upton Park Barking Road West Ham FC Burges Road Red discs show the bus stop you need for your chosen PARK East Beckton r bus service. The disc ,a appears on the top of the bus stop Showcase Cinema 1 2 3 Barking Road 4 5 6 in the street (see map of town centre in centre of diagram). Plaistow High Street Samson Street Park Avenue Balaam Street Greengate Street East Beckton Balaam Street Gad Close Sewell Street Triangle Retail Park Barking Road Folkestone Road New City Road Route finder Balaam Street Balaam Park Health Centre High Street South East Beckton Lonsdale Avenue Sainsbury’s Day buses 325 Bus route Towards Bus stops Plaistow Barking Road Abbey Arms Plaistow Police Station Woolwich Manor Way Albatross Close 147 Ilford ,l ,t The yellow tinted area includes every ,f ,s Barking Road bus stop up to about one-and-a-half miles 241 Stratford City Bus Station Chargeable Lane Plaistow Woolwich Manor Way Greengate Tollgate Road from ExCeL (Docklands). -

Capital Ring Section 14 Hackney Wick to Beckton District Park

Capital Ring Directions: On leaving the station look out for the Capital Ring signs and Section 14 follow them to the left along Hepscott Road to the main road. Turn left along Rothbury Road A and cross over the canal bridge. Then turn right down the Hackney Wick to Beckton District Park steep cobbled ramp onto the Lee Navigation towpath. The River Lea and Lea Valley and the canal known as Lee Navigation refer to the same piece of water. There were disputes about the spelling for a Version 4 : May 2012 long time and to settle them it was decided that the natural aspects of the river, such as the river itself, would be LEA and manmade features such as Start: Hackney Wick (TQ372845) the canal would be LEE. Station: Hackney Wick Finish: Beckton District Park (Stansfeld Road) Keep straight ahead on the towpath, going over the cobbled bases for the cranes that loaded and unloaded the boats. (TQ422811) Station: Royal Albert DLR Carry on to Old Ford Lock B where you cross over the River Lea which Distance: 5.2 miles ( 8.3 km) joins the Navigation here. Introduction: This is a surprisingly green, easy walk of just over 5 miles (8 The route passes a red brick house with a large garden which was originally km). The route passes the site of the Olympic Park so at times there may be the Lock Keeper’s Cottage but more recently was used for the Big Breakfast diversions – which will be signed. Much of the route is on a traffic-free, firm Show until it came to end in 2002. -

Capital Ring’ in Celebration of the Trefoil Guild’S 75Th Anniversary

London Walkers and Talkers are walking London’s ‘Capital Ring’ in celebration of the Trefoil Guild’s 75th Anniversary. Will you join us to walk one or all of the 15 section 78 mile circular route? Maybe we’ll take a 3 mile short cut somewhere! The Capital Ring Walk offers you the chance to see some of London's finest scenery. Divided into 15, easy-to-walk sections, it covers 78 miles (126KM) of open space, nature reserves, Sites of Specific Scientific Interest and more. https://tfl.gov.uk/modes/walking/capital-ring All walks will take place on Sundays and start at 11.00am unless otherwise stated. Check out the Capital Ring website for detailed descriptions of the walk. Sections average 5 miles (8km) but you can choose to leave the route at any point and walk as far as you like. If you miss a group walk you could make it up at any time during the year. Our final walk will end with a celebratory picnic at the Maze in Crystal Palace Park in July 2018! Will there be a badge? Of course, we’ll be looking at designing a celebratory badge! How do I sign up? Please check the LaSER Trefoil Guild or Girlguiding London South West websites for confirmation of each walk and email Pip at [email protected] so that we know to expect you. The walks cover mixed terrain, details will be posted on the above websites each month but please come prepared for a challenging walk at a reasonable speed. -

BRITISH OPEN KARATE CHAMPIONSHIPS 2019 SUNDAY 5Th MAY 2019 CLOSING DATE: MIDNIGHT SUNDAY 28Th APRIL 2019

BRITISH OPEN KARATE CHAMPIONSHIPS 2019 SUNDAY 5th MAY 2019 CLOSING DATE: MIDNIGHT SUNDAY 28th APRIL 2019 UNIVERSITY OF EAST LONDON - SPORTSDOCK 4-6 UNIVERSITY WAY LONDON E16 2RD Competition entry forms from: Tel: + 44(0)7834 02 4116 Email: [email protected] Web: www.eskfkarate.co.uk Individual Entries - £20 Team entries - £30 ALL FEDERATIONS AND CLUBS ARE WELCOME - NO RESTRICTIONS – NO POLITICS STRICTLY NO ENTRIES ON THE DAY RULES and REGULATIONS ON THE DAY KATA All kata categories will be judged by points as per WUKF rules, http://www.wukf-karate.org/upload/201308100926088.pdf with slight amendments as judged necessary by the organisers. • Seven (7) Tatamis will be used throughout the day. • All kata (individual and team) will be judged in 2 rounds. The Chief Referee on each area will inform competitors of the two rounds. • For 13 years and under, competitors MUST perform a Shitei kata (i.e Heian, Pinan or equivalent) in the First round. For the second round, competitors may perform any Open kata of their choice. • For 14 years and over, competitors may perform any 2 katas of their choice, and may repeat the kata in subsequent rounds. • If the same 2 competitors tie twice, final decision will be taken by flag. • Athletes can compete with their own coloured belts. • There may be amalgamations of categories if there are not enough entries in the said events as per WUKF rules. • Kindly note that in team kata, there will also be 2 rounds depending on the number of teams regsitered. Competitors may repeat their kata in each round. -

TON Fully Refurbished

Unit 84 BECKTON Fully Refurbished INDICATIVE IMAGE INDUSTRIAL / WAREHOUSE UNIT TO LET 5,914 ft2 (549.63 m2) www.ipif.com/rodingroad LONDON INDUSTRIAL PARK, RODING ROAD BECKTON, LONDON, E6 6LS M25 A11 A1202 LONDON A12 A13 BECKTON INDUSTRIAL PARK A1020 LOCATION A13 BECKTON London Industrial Park is located to the south side of the A13 A1023 A1261 EXCEL LONDON off the Woolwich Manor Way (A117) with Roding Road being a LONDON BRIDGE RENT A100 CANARY WHARF continuation of the main Alpine Way estate road. The A13 BLACKWALL LONDON On application. TUNNEL CITY AIRPORT provides a direct link to both the M25 (Junction 30), the City RIVER THAMES and the Blackwall Tunnel together with the A406 North BUSINESS RATES A102 Circular Road which provides a direct link to the M11 Motorway. Available upon request. ISLE OF DOGS Beckton DLR station is approximately 10 minutes walk from A2 the property and the estate is therefore easily accessible by SERVICE CHARGE CUTTY SARK both private and public transport. ROYAL GREENWICH A service charge is levied for the upkeep and maintenance of OBSERVATORY DESCRIPTION the common areas. Further details are available upon request. The property is a recently refurbished industrial/warehouse unit of steel portal frame construction with profile steel LEGAL COSTS cladding under a pitched roof incorporating transluscent Each party will be responsible for their own legal costs incurred A406 roof panels. in this transaction. HIGH ST SOUTH • 24 hour on-site security VAT • First floor offices All figures quoted are exclusive of VAT, which is applicable on all • Secure forecourt parking/loading facilities IPIF Estates. -

Beckton District Park to Woolwich

Capital Ring section 15 page 1 CAPITAL RING Section 15 of 15 Beckton District Park to Woolwich Section start: Beckton District Park (Stansfield Road) Nearest station to start: Royal Albert (DLR) Section finish: Woolwich Foot Tunnel Nearest station to finish: Woolwich Arsenal (Rail or DLR) Section distance 3.5 miles plus 0.9 miles of station links Total = 4.4 miles (7.1 km) Introduction This section is almost entirely on level tarmac paths and pavements. It Note explores the once very industrial area of Beckton, some former docks and Occasionally the path to travels alongside the River Thames to the foot tunnel at Woolwich. the second lock gates at the King George V dock This section is affected by development work as shown on the maps. It is is closed by a locked gate. This happens still open but you have to follow alternative routes described here. during maintenance work. To avoid an The main Capital Ring route involves flights of steps, lock gates and an unwelcome surprise, call isolated length of path that can seem daunting for someone walking alone. the Gallions Point Fortunately there are alternative routes to avoid these challenges. From Marina: 0743 626 0458 time to time the signposted route across the lock gates at King George V or 0207 476 7054. dock is closed by a locked gate for maintenance or other reasons. If so, it Alternatively email: info@gallionspointmarin will be necessary to use the alternative route along the A117. a.co.uk. If the route is closed follow the Points of interest along this section include: the University of East London alternative step-free Campus, built over Cyprus station; Royal Albert dock – now an Olympic route (see page 4). -

Capital Ring Section 14 of 15

Transport for London. Capital Ring Section 14 of 15. Hackney Wick to Beckton District Park. Section start: Hackney Wick. Nearest stations Hackney Wick . to start: Section finish: Beckton District Park (Stansfeld Road). Nearest station Royal Albert . to finish: Section distance: 5.2 miles (8.3 kilometres). Introduction. This is a surprisingly green, easy walk. The route passes the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, so at times there may be diversions. Much of the route is on a traffic-free, firm level path which, uniquely, is on top of some of London's sewers. There are some gentle slopes and some steps, often with adjacent ramps. The walk goes alongside Lee Navigation to Old Ford Lock, onto the Greenway, past the wonderful Abbey Mills Pumping Station and ends in Beckton District Park. Pubs and cafes can be found at Hackney Wick, Plaistow and Beckton District Park. Trains and tubes are available along this section and there are many buses along the way. There is a link to the start of the walk from Hackney Wick Station, which is served by National Rail. Continues Continues on next page Directions On leaving Hackney Wick station look out for the Capital Ring signs and follow them to the left along Hepscott Road to the main road. Turn left along Rothbury Road and cross over the canal bridge. Then turn right down the steep cobbled ramp onto the Lee Navigation towpath. Keep straight ahead on the towpath, going over the cobbled bases for the cranes that loaded and unloaded the boats. Carry on to Old Ford Lock where you cross over the River Lea which joins the Navigation here. -

Organisation Applicant Project Project Description Location Funding

Organisation Applicant Project Project description Location Funding requested £ West Silvertown West Silvertown Improvements to Britannia Our vision is to transform Britannia Village (BV) green into a well-loved, inclusive Britannia Village Green, £20,000 Foundation Foundation Village Green environment. BV is lacking “bumping spaces” – we have very few amenities, and the green Hanameel Street, currently feels likea thorough fare rather than a destination. This project aims to create an London, UK intergenerational space for neighbours to meet, build relationships and share life: a true village green.We will do this through: Play equipment: We will work with local children to design a play area, and where possible will create opportunities for the community to be part of the building process.Trees and greenery: We will create opportunities for local residents to connect with nature through plants - including more trees to create shade, rain cover and cleaner air. We would also like to plant flowers to create beauty in the space.Paths: Over the past 20 years residents have worn a mud path through the grass. We will recognise this as a proper path by paving it. Benches: We will place new benches around the green, creating safe places to sit and socialise.This bid will be used for detailed community consultation, building a path and benches, and to secure a partner and further funding for play equipment. Friends of Beckton Brian Provide wheelchair access For the last 2 years we have restored this 20 year abandoned park/pond and have been re- Beckton Small Ponds, £4,970 Small Ponds Pittendrigh to ponds and replace establishing basic infrastructure, creating gardens and improving the water quality for natural Beckton Corridor, derelict viewing platform life.