Education Version 1.0

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preparatory School Handbook for Parents September 2020

Preparatory School Handbook for Parents September 2020 Ages 7 - 13 years PREPARATORY SCHOOL WELCOME : WELCOME Welcome to the Dean Close Preparatory School Handbook for Parents and Guardians. The purpose of this Handbook is, above all else, to be a help to you as parents as your child embarks on their time at Dean Close Preparatory School. We count it as a wonderful privilege to be involved in the formation of young lives. The relationship which we cultivate with you is at the heart of our success and we look forward to working in close partnership with you. The Handbook does not set out to replace, but rather complement, the important personal communication which will continue throughout your child’s time with us. We hope it will come to be an important source of information. We have done all we can to make sure that most questions about policies, academic structure and our pastoral system are answered within these pages, along with the more important day to day information such as dress codes, timetables and contact details. Paddy Moss ~ Headmaster FOR PARENTS 2020 HANDBOOK PREPARTORY SCHOOL CONTENTS : CONTENTS Page Page Page CONTACTING THE SCHOOL 3 CHORISTERS 13 COMMUNICATION AND PARENTAL LINKS 25 The Office 3 The Staff 13 The Staff 3 Contact Details 13 The Welcome Pack 25 The Houses 3 School Uniform 13 Publications 25 Day Houses 3 Choristers’ Daily Schedule 13 The Weekly Bulletin 25 Boarding Houses 3 Hermes 25 Other Useful Numbers SPEECH AND DRAMA 14 E-News 25 and Email Addresses 4 The Young Decanian 25 Website/Extranet 4 Drama 14 Contacting -

End of Term Mailing Lent Term 2019

END OF TERM MAILING LENT TERM 2019 HEADMISTRESS: DR CAROLYN SHELLEY B.ED (HONS) PHD DIRECT LINE: 01242 258079 EMAIL: [email protected] 29th March 2019 Dear Parents, The last two weeks of this term have been very busy across the school, including, as you know, welcoming inspectors to the school to see all the wonderful work we do, including some of our WOW days. The children enjoyed showing their work and were a great credit to the school. Thank you for taking part in the parental survey and feeding into the process - the report is now being finished and we look forward to sharing the results with you in about seven weeks time. In the second half of term, we have held some exciting WOW days linked with topic work, both further afield and at school; Year Two had a fantastic Space Day at school, dressing in amazing costumes and learning many new facts, and Year One had a fantastic visit to ThinkTank Birmingham, linking with their Science topics and returning home full of information about Forces, the Body, and fossils and skeletons! Reception invited other year groups to join them in their Space Day when they investigated constellations and the planets in the ‘Wonderdome’ an amazing planetarium in our Pre-Prep hall. The children were fascinated and they then went on to find out more planet facts and to create their own constellations in the classrooms. Lastly, we all celebrated World Book Day with a focus on poetry this year; we had fun sharing our favourite poems or rhyming stories, reading with buddies, carrying out a rhyming quiz around the school and, of course, becoming poets ourselves. -

Strategic Review of Secondary Education Planning for Cheltenham

Strategic review of Secondary Education Planning for Cheltenham January 2017 1 Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................. 2 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 3 Supporting data .................................................................................................................................. 3 Current number on roll ....................................................................................................................... 3 Pupil forecasts 2015/16 ...................................................................................................................... 4 Planned local housing developments ................................................................................................. 4 Strategic Housing ................................................................................................................................ 5 Recommendation, Land and Footnotes....………………………………………………………………………………………6 Executive Summary There has been pressure on local primary school places in Cheltenham since 2011. This is the result of a change in the birth rate locally and natural changing demographics, coupled with some local housing growth. This growth has been significant and resulted in the need to provide additional temporary and permanent school places at existing primary schools. -

Secondary School and Academy Admissions

Secondary School and Academy Admissions INFORMATION BOOKLET 2021/2022 For children born between 1st September 2009 and 31st August 2010 Page 1 Schools Information Admission number and previous applications This is the total number of pupils that the school can admit into Year 7. We have also included the total number of pupils in the school so you can gauge its size. You’ll see how oversubscribed a school is by how many parents had named a school as one of their five preferences on their application form and how many of these had placed it as their first preference. Catchment area Some comprehensive schools have a catchment area consisting of parishes, district or county boundaries. Some schools will give priority for admission to those children living within their catchment area. If you live in Gloucestershire and are over 3 miles from your child’s catchment school they may be entitled to school transport provided by the Local Authority. Oversubscription criteria If a school receives more preferences than places available, the admission authority will place all children in the order in which they could be considered for a place. This will strictly follow the priority order of their oversubscription criteria. Please follow the below link to find the statistics for how many pupils were allocated under the admissions criteria for each school - https://www.gloucestershire.gov.uk/education-and-learning/school-admissions-scheme-criteria- and-protocol/allocation-day-statistics-for-gloucestershire-schools/. We can’t guarantee your child will be offered one of their preferred schools, but they will have a stronger chance if they meet higher priorities in the criteria. -

Annual Review 2015 - 2016 Transforming Lives, Supporting Business

Annual Review 2015 - 2016 Transforming Lives, Supporting Business www.gloscol.ac.uk Contents From the Chair 2 From the Chair and the Principal and the Principal Chair’s Welcome Further Education Colleges (FE) make the difference 3 Our Provision between the next steps on to the ladder of a worthwhile Meeting the Skills career, or settling for low paid jobs. Colleges are the choice of significantly more young adults than universities Needs of the County each year and help ensure a professional, technically skilled workforce can help grow the UK economy. 4 Investing to Meet the The Board of Gloucestershire College believes passionately in the value of Further Education in the county Needs of the County to meet the demands of labour markets, employers and students. 5 Transforming Lives That is why it is determined to continue its mission to upskill students and help them progress into a world of better paid work. Gloucestershire College students must leave for their destinations Student Success equipped, not just by training but also by hands-on experience. That is why, in 2015, the College invested directly in successful businesses, such as Graduations at no.9 and Chelsea Bar and Brasserie to name but two of several, in which students become immersed in the real world of work 6 Supporting Business and use the practical skills they have learned. Initiatives like these, combined with an increased emphasis on the teaching of Science, Technology, English and Maths (STEM), will ensure students leave work-ready to meet the needs of Gloucestershire’s employers. 7 Supporting our The world of FE is changing, significantly and fast! That is why Gloucestershire College is changing Community too, as part of its Strategic Plan, to provide greater organisational agility and a more effective operation which maintains and enhances the focus on students and employers as the key drivers of the organisation. -

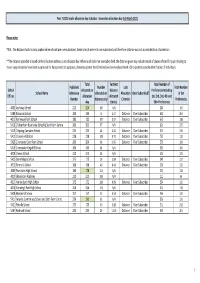

Secondary Allocation Day 2021 V3.Xlsx

Year 7 2021 intake allocation day statistics - Secondary allocation day 1st March 2021 Please note: *N/A - The distance factor is only applied when schools are oversubscribed, these schools were not oversubscribed and therefore distance was not a consideration of admission. **The distance provided is based on the allocation address as at allocation day. Where a school is not oversubscribed, the distance given may include details of places offered for pupils hoping to move. Large distances have been suppressed for data protection purposes, distances greater that 20 miles have been replaced with >20 to protect possible identification of individuals. Total Furthest Total Number of Published Number Last Total Number School allocated on distance Preferences Including School Name Admission allocated on Allocation Over Subscribed? of 1st DfE no. allocation allocated 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th and Number distance only Criterion Preferences day (miles) 5th+ Preferences 4032 Archway School 215 214 100 N/A 280 109 5408 Balcarras School 194 194 8 1.47 Distance Over Subscribed 602 204 4012 Barnwood Park School 180 180 107 0.97 Distance Over Subscribed 678 238 5418 Cheltenham Bournside School & Sixth Form Centre 300 300 97 N/A 620 225 5414 Chipping Campden School 225 225 46 5.62 Distance Over Subscribed 353 219 5412 Chosen Hill School 228 228 138 9.50 Distance Over Subscribed 737 115 5420 Cirencester Deer Park School 209 209 96 10.67 Distance Over Subscribed 576 182 5419 Cirencester Kingshill School 196 196 64 N/A 303 166 4024 Cleeve School 310 310 94 N/A -

Gloucestershire School Aged Immunisation Pathways for the 2020/21 Academic Year

Gloucestershire School Aged Immunisation Pathways for the 2020/21 academic year Introduction This information aims to support local practices in understanding the school aged immunisations programme for the 2020/21 academic year, including any changes to the schedule. We hope you find this information useful and clear: if you have any comments, suggestions or queries please contact the South West Screening and Immunisations Team on [email protected]. COVID-19 Due to the impact of COVID-19 and school closures in the first half of 2020, the school aged immunisation provider will be offering catch-up doses of Meningitis ACWY, Td/IPV and HPV during the 2020/21 academic year to those cohorts that missed their scheduled doses in the 2019/20 academic year – see below for further details. Overview of school aged immunisations From September 2020, the following immunisations will be delivered by the school aged immunisation provider: • Influenza: Reception to year 7 in mainstream schools, and reception to 18 years old in special schools • HPV dose 1: Year 8 girls and boys (and catch-up doses to girls and boys who missed a dose in 2019/20 and are now in year 9) • HPV dose 2: Year 9 girls and boys (and catch-up doses to girls only who missed a dose in 2019/20 and are now in year 10) • Men ACWY: Year 9 (and catch-up doses to girls and boys who missed a dose in 2019/20 and are now in year 10) • Td/IPV: Year 9 (and catch-up doses to girls and boys who missed a dose in 2019/20 and are now in year 10) Page 1 Gloucestershire School Aged Immunisation Pathways for the 2020/21 academic year In Gloucestershire the school aged immunisation provider will continue to follow up all secondary aged children who have missed any vaccinations at school until they leave in Year 11. -

Annual Review 2016-2017

Annual Review 2016-2017 - Learning that works Contents 1.0 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ 3 2.0 Our Provision: Learning that Works ................................................................................................................. 4 3.0 Investing to Meet the Needs of the County...................................................................................................... 6 4.0 Transforming Lives - Student Success ............................................................................................................ 9 5.0 Supporting Business........................................................................................................................................... 10 5.1 Superdry: Redefining apprenticeships ............................................................................................................. 12 6.0 Supporting our Community .................................................................................................................................... 14 7.0 Working in Partnership ........................................................................................................................................... 16 8.0 Staff Equipped to Support Success.................................................................................................................. 18 9.0 Governance......................................................................................................................................................... -

Sheet1 Page 1 Express & Star (West Midlands) 113,174 Manchester Evening News 90,973 Liverpool Echo 85,463 Aberdeen

Sheet1 Express & Star (West Midlands) 113,174 Manchester Evening News 90,973 Liverpool Echo 85,463 Aberdeen - Press & Journal 71,044 Dundee Courier & Advertiser 61,981 Norwich - Eastern Daily Press 59,490 Belfast Telegraph 59,319 Shropshire Star 55,606 Newcastle-Upon-Tyne Evening Chronicle 52,486 Glasgow - Evening Times 52,400 Leicester Mercury 51,150 The Sentinel 50,792 Aberdeen - Evening Express 47,849 Birmingham Mail 47,217 Irish News - Morning 43,647 Hull Daily Mail 43,523 Portsmouth - News & Sports Mail 41,442 Darlington - The Northern Echo 41,181 Teesside - Evening Gazette 40,546 South Wales Evening Post 40,149 Edinburgh - Evening News 39,947 Leeds - Yorkshire Post 39,698 Bristol Evening Post 38,344 Sheffield Star & Green 'Un 37,255 Leeds - Yorkshire Evening Post 36,512 Nottingham Post 35,361 Coventry Telegraph 34,359 Sunderland Echo & Football Echo 32,771 Cardiff - South Wales Echo - Evening 32,754 Derby Telegraph 32,356 Southampton - Southern Daily Echo 31,964 Daily Post (Wales) 31,802 Plymouth - Western Morning News 31,058 Southend - Basildon - Castle Point - Echo 30,108 Ipswich - East Anglian Daily Times 29,932 Plymouth - The Herald 29,709 Bristol - Western Daily Press 28,322 Wales - The Western Mail - Morning 26,931 Bournemouth - The Daily Echo 26,818 Bradford - Telegraph & Argus 26,766 Newcastle-Upon-Tyne Journal 26,280 York - The Press 25,989 Grimsby Telegraph 25,974 The Argus Brighton 24,949 Dundee Evening Telegraph 23,631 Ulster - News Letter 23,492 South Wales Argus - Evening 23,332 Lancashire Telegraph - Blackburn 23,260 -

Publication Changes During the Fieldwork Period: January – December 2015

PUBLICATION CHANGES DURING THE FIELDWORK PERIOD: JANUARY – DECEMBER 2015 Publication Change Fieldwork period on which published figures are based Hello! Fashion Monthly Launched September 2014. No figures in this report. Added to the questionnaire January 2015. It is the publishers’ responsibility to inform NRS Ltd. as soon as possible of any changes to their titles included in the survey. The following publications were included in the questionnaire for all or part of the reporting period. For methodological or other reasons, no figures are reported. Amateur Photographer International Rugby News Stylist Animal Life Loaded Sunday Independent (Plymouth) Asian Woman Lonely Planet Magazine Sunday Mercury (Birmingham) ASOS Mixmag Sunday Sun (Newcastle) Athletics Weekly Moneywise Superbike Magazine BBC Focus Morrisons Magazine T3 Biking Times Natural Health TNT Magazine Bizarre Next Total Film The Chap Perfect Wedding Trout Fisherman Classic and Sportscar Pregnancy & Birth Uncut Digital Camera Prima Baby & Pregnancy Viz The Economist Psychologies Magazine Wales on Sunday Film Review Running Fitness The Weekly News Financial Times Sailing Today What Satellite & Digital TV Garden Answers Scotland in Trust WSC When Saturday Comes Garden News Sight & Sound Geographical Shortlist Gramophone Shout Health & Fitness Sorted Hi-Fi News The Spectator High Life Sport Regional Newspapers – Group Readership Data Any regional morning/evening Any regional evening All titles listed below All titles listed below Regional Daily Morning Newspapers Regional Daily -

241 Cirencester Road Charlton Kings W Cheltenham W Gloucestershire W Gl53 8Eb 241 Cirencester Road

241 CIRENCESTER ROAD charlton kings w cheltenham w gloucestershire w gl53 8eb 241 CIRENCESTER ROAD charlton kings w cheltenham w gloucestershire w gl53 8eb A WONDERFUL RENOVATED AND EXTENDED PERIOD SEMI-DETACHED PROPERTY WITH A FABULOUS CONTEMPORARY EXTENSION WITH BIFOLD DOORS, IN THE BALCARRAS SCHOOL CATCHMENT AREA Entrance porch w entrance hall w sitting room w snug w study w utility room w cloakroom w open plan living/dining/kitchen w master bedroom with en suite shower room w three further double bedrooms w family bathroom Good sized rear garden with wide patio w 229 square foot outbuilding currently used as a summer house/ occasional guest accommodation and tool shed w gravelled parking to the front In addition, on the ground floor, are two further reception situation rooms, including a working fireplace, a study, a fitted utility / Charlton Kings is an incredibly sought-after residential district boot room, and a cloakroom. The recent downstairs side and located to the south of Cheltenham town centre, with excellent rear extension includes underfloor heating throughout. access to the town itself and local facilities. There are four double bedrooms, including a master bedroom 241 Cirencester Road is located on the edge of Charlton Kings with new en suite shower room, and a recently installed family but well within effective catchment for Balcarras School and a bathroom serving the remaining three bedrooms. short walk to Timbercombe Wood, Hotel Gym and Sainsbury’s Local. There is an unusually large and private garden to the rear, mostly laid to lawn but with a wide patio immediately Cheltenham is famed as one of the most complete Regency to the rear of the house. -

24 from Gloucester to Cinderford & Chepstow 24 from Chepstow to Cinderford to Gloucester

24 from Gloucester to Cinderford & Chepstow Mondays to Saturdays MF Sat MF Sat MF FS 24 24 24 24 24 24 24 24 24 24 24 24A 24 24A 24 24 24 Gloucester Transport Hub [H] 1020 1220 1420 1420 1520 1520 1625 1640 1720 1730 1930 2130 2310 Churcham Bulley Lane 1034 1234 1434 1434 1534 1534 1639 1654 1734 1744 1943 2143 2323 Huntley Red Lion 1038 1238 1438 1438 1538 1538 1643 1658 1738 1748 1946 2146 2326 Mitcheldean Lamb 0714 1049 1249 1449 1449 1549 1549 1654 1709 1749 1759 1956 2156 2336 Drybrook Cross 0720 1055 1255 1455 1455 1555 1555 1700 1715 1755 1805 2001 2201 2341 Cinderford Bus Station 0733 1108 1308 1508 1508 1608 1608 1713 1728 1808 1818 2013 2213 2353 ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ Cinderford Bus Station 0652 0912 1112 1312 1512 1512 1612 1622 1732 1822 Cinderford Forest High School - - - - - 1517 - - - - Cinderford Gloucestershire College - - - - - - 1620 - - Ruspidge Stores 0659 0919 1119 1319 1519 1524 1629 1629 1739 1829 Upper Soudley White Horse 0704 0924 1124 1324 1524 1529 1634 1634 1744 1834 Blakeney Orchard Gate 0714 0934 1134 1334 1534 1539 1644 1644 1754 1844 Yorkley Bailey Inn - - - - - - - - 1800 1850 Whitecroft Post Office - - - - - - - - 1805 1855 Parkend Station - - - - - - - - 1810 1900 Ellwood Ellwood Cross - - - - - - - - 1817 1907 Lydney Bus Station 0635 0725 0945 1145 1345 1540 1545 1655 1655 Alvington Globe Inn 0642 0732 0952 1152 1352 1702 1702 Tutshill Police Station 0657 0747 1007 1207 1407 1717 1717 Chepstow Bus Station 0702 0752 1012 1212 1412 1722 1722 MF This journey only runs on Mondays to Fridays Sat This journey