Greylingstad Mpumalanga Done by Do

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Restorica 22 1987.Pdf

South Africa's architectural heritage is constantly respect for the preservation of our traditional skills. threatened by sad neglect and - often - demolition. By combining our inherent expertise with modern There is, therefore, a continuing need for the project management techniques, the name of Gordon dedicated restoration and refurbishing of our beautiful Verhoef & Krause has become synonymous with the historical buildings. superior and efficient craftsmanship vital for the For 25 years, our commitment has been to fill that preservation of our buildings. need. Today, the company is striving to maintain this Throughout the country, Gordon Verhoef &Krause leading position as a major developer of restored has established teams of ~--don~l...-.-&.. properties and as a main con- experienced artisans, all \:1\..11 1 I 1\.1\:1 ' 7.. tractor in the recycling of buildings, craftsmen in their individual raUSC! .. endeavouring to improve the overan fields. They all have a quality of life in our environment. 25 Johannesburg 6146511 • Cape Town 45 5575 • Port Elizabeth 52 4094 • Durban 30 14317 • Pretoria 26 0555 • Windhoek 2 5641 London 735 8636 • Manchester 789 7105 Editorial Stigting Simon van der Stel Foundation (Ingelyfde Vereniging sander winsoogmerk Cape St. Francis Lighthouse Incorporated Association not for gain.) H. L. Huisman Opgerig/Established 8 Aprill959. Reg. No. 60/00005/08 The architectural background to the restoration of the Magtigingsnommer/Fundraising number: Schreiner House, Cradock F02 200215 000 8 Prof. ]. C. Radford Posbus/P.0. Box 17 43, Pretoria 000 l Briewe Nasionale Raad/National Council Nasionale Voorsitter!National Chairman Prince Albert se gewelhuise het wonderlik behoue gebly. Prof. -

The Health and Health System of South Africa: Historical Roots of Current Public Health Challenges

Series Health in South Africa 1 The health and health system of South Africa: historical roots of current public health challenges Hoosen Coovadia, Rachel Jewkes, Peter Barron, David Sanders, Diane McIntyre The roots of a dysfunctional health system and the collision of the epidemics of communicable and non-communicable Lancet 2009; 374: 817–34 diseases in South Africa can be found in policies from periods of the country’s history, from colonial subjugation, Published Online apartheid dispossession, to the post-apartheid period. Racial and gender discrimination, the migrant labour system, August 25, 2009 the destruction of family life, vast income inequalities, and extreme violence have all formed part of South Africa’s DOI:10.1016/S0140- 6736(09)60951-X troubled past, and all have inexorably aff ected health and health services. In 1994, when apartheid ended, the health See Editorial page 757 system faced massive challenges, many of which still persist. Macroeconomic policies, fostering growth rather than See Comment pages 759 redistribution, contributed to the persistence of economic disparities between races despite a large expansion in and 760 social grants. The public health system has been transformed into an integrated, comprehensive national service, but See Perspectives page 777 failures in leadership and stewardship and weak management have led to inadequate implementation of what are This is fi rst in a Series of often good policies. Pivotal facets of primary health care are not in place and there is a substantial human resources six papers on health in crisis facing the health sector. The HIV epidemic has contributed to and accelerated these challenges. -

Gauteng Gauteng

Gauteng Gauteng Thousands of visitors to South Africa make Gauteng their first stop, but most don’t stay long enough to appreciate all it has in store. They’re missing out. With two vibrant cities, Johannesburg and Tshwane (Pretoria), and a hinterland stuffed with cultural treasures, there’s a great deal more to this province than Jo’burg Striking gold International Airport, says John Malathronas. “The golf course was created in 1974,” said in Pimville, Soweto, and the fact that ‘anyone’ the manager. “Eighteen holes, par 72.” could become a member of the previously black- It was a Monday afternoon and the tees only Soweto Country Club, was spoken with due were relatively quiet: fewer than a dozen people satisfaction. I looked around. Some fairways were in the heart of were swinging their clubs among the greens. overgrown and others so dried up it was difficult to “We now have 190 full-time members,” my host tell the bunkers from the greens. Still, the advent went on. “It costs 350 rand per year to join for of a fully-functioning golf course, an oasis of the first year and 250 rand per year afterwards. tranquillity in the noisy, bustling township, was, But day membership costs 60 rand only. Of indeed, an achievement of which to be proud. course, now anyone can become a member.” Thirty years after the Soweto schoolboys South Africa This last sentence hit home. I was, after all, rebelled against the apartheid regime and carved ll 40 Travel Africa Travel Africa 41 ERIC NATHAN / ALAMY NATHAN ERIC Gauteng Gauteng LERATO MADUNA / REUTERS LERATO its name into the annals of modern history, the The seeping transformation township’s predicament can be summed up by Tswaing the word I kept hearing during my time there: of Jo’burg is taking visitors by R511 Crater ‘upgraded’. -

13 Mpumalanga Province

Section B: DistrictProfile MpumalangaHealth Profiles Province 13 Mpumalanga Province Gert Sibande District Municipality (DC30) Overview of the district The Gert Sibande District Municipalitya is a Category C municipality located in the Mpumalanga Province. It is bordered by the Ehlanzeni and Nkangala District Municipalities to the north, KwaZulu-Natal and the Free State to the south, Swaziland to the east, and Gauteng to the west. The district is the largest of the three districts in the province, making up almost half of its geographical area. It is comprised of seven local municipalities: Govan Mbeki, Chief Albert Luthuli, Msukaligwa, Dipaleseng, Mkhondo, Lekwa and Pixley Ka Seme. Highways that pass through Gert Sibande District Municipality include the N11, which goes through to the N2 in KwaZulu-Natal, the N17 from Gauteng passing through to Swaziland, and the N3 from Gauteng to KwaZulu-Natal. Area: 31 841km² Population (2016)b: 1 158 573 Population density (2016): 36.4 persons per km2 Estimated medical scheme coverage: 13.5% Cities/Towns: Amersfoort, Amsterdam, Balfour, Bethal, Breyten, Carolina, Charl Cilliers, Chrissiesmeer, Davel, Ekulindeni, Embalenhle, Empuluzi, Ermelo, Evander, Greylingstad, Grootvlei, Kinross, Leandra, Lothair, Morgenzon, Perdekop, Secunda, Standerton, Trichardt, Volksrust, Wakkerstroom, eManzana, eMkhondo (Piet Retief). Main Economic Sectors: Manufacturing (57.4%), agriculture (41.4%), trade (25.8%), transport (24.5%), finance (21.2%), mining (14.1%), community services (12.3%), construction (2.1%). Population distribution, local municipality boundaries and health facility locations Source: Mid-Year Population Estimates 2016, Stats SA. a The Local Government Handbook South Africa 2017. A complete guide to municipalities in South Africa. Seventh edition. Accessible at: www. -

Government Notice No

6 No. 28552 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 3 MARCH 2006 GOVERNMENT NOTICES GOEWERMENTSKENNISGEWINGS DEPARTMENT OF ARTS AND CULTURE DEPARTEMENT VAN KUNS EN KULTUUR No. 185 3 March 2006 APPROVAL OF OFFICIAL GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES I, Z, Pallo Jordan, Minister of Arts and Culture officially approved the following geographical names on the advice of the South African Geographical Names Council on 1I November 2005. Dibaba (change of name from A settlement 10 km W of Carolina in Diepgezet) Mpumalanga Ekhandizwe (change of name from A settlement 65 km S of Globlersdal in Louis Creek) Mpumalanga eKulindeni A settlement 20 km S of Badplaas in Mpumalanga eMalahleni (change of name from A town (formerly Witbank) situated 30 Witban k) km E of Middleburg in Mpumalanga eMpuluzi A river 85 km W of Carolina in Mpumalanga eNdlulamithini (change of name from A settlement 6 km W of Standerton in Kaffirskraalkopie) Mpumalanga Engodlomezi (change of name from A mountain 86 km W of Carolina in SYd4 Mpumalanga eNtambende 1 (change of name from A settlement 9 W of Carolina in Devet) Mpumalanga eNtambende 11 (change of name from A settlement 9 W of Carolina in Nordeen) Mpumalanga STAATSKOERANT, 3 MAART 2006 No. 28552 7 eSilobela A township 1 km W of Carolina in Mpumafanga Etikhulungwane (change of name from A settlement 93 km SW of Carolina in Diepdale) Mpumalanga Etikwentsaba Estate A settlement 3 km W of Hazyview in Mpumalanga Ezimbuthumeni (change of name from A settlement 50 km E of Standerton in Kaffirskraal) Mpumalanga Ga-Morwe (change of name from A settlement f 7 km -

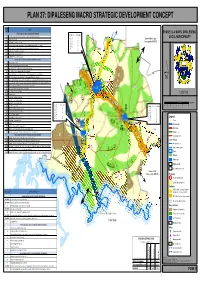

Dipaleseng Macro Strategic Development Concept

PLAN 37: DIPALESENG MACRO STRATEGIC DEVELOPMENT CONCEPT Project Projects No SPATIAL OBJECTIVE: EXPLOIT ECONOMIC OPPORTUNITIES T 7 PHASE 3 & 4 MAPS: DIPALESENG PROJECTS: STRATEGIES: o 1 N /N 1 Compilation of an implementation plan to create mining enabling environment 17 18 C n i o g v LOCAL MUNICIPALITY 2 Beneficiation of coal 24 28 D e e Govan Mbeki Local 29 35 F l D o F Municipality (MP307) 3 (n/a) Development of a Tourism Strategy 38 43 G T 4 (n/a) Access suitable land for irrigation farming and beneficiation of agricultural products 44 46 H 47 50 I 5 (n/a) Access agricultural support programmes for the development of arable land 52 J 1! 7 (n/a) Beneficiation of agricultural products K 23! 8 (n/a) Implement land reform Programme L L 8 15 (n/a) SMME/BEE Development Programmes 4 5 SPATIAL OBJECTIVE: CREATE SUSTAINABLE HUMAN SETTLEMENTS R 17 Thusong service centres. F 18 Draft detailed Urban Design Framework for nodes E P e t r u s v d M e r w e ! 19 Upgrade of the R23 road between Greylingstad and Balfour P e t r u s v d M e r w e 1 1 5 HHaarrooffff DDaamm 20 Upgrade of the R51 road between Balfour and Grootvlei R 21! 21 Maintain R23 transport corridor to the east of Greylingstad and to the north of Balfour N 22 (n/a) Upgrade gravel access roads to schools to enable public transport provision 23 Maintain R51-R548 main road south of Grootvlei (to Vaal River) and north of Balfour (to Devon, Secunda) F 55! ´ S i y a t h e m b a 24 Develop services master plans (roads, water, sewer, electricity) for Balfour, Greylingstad and Grootvlei T S i y a t h e m b a o 28 Identification of new cemetery and land fill sites in all main towns H / ! B 1 ! e /!!! 53 L B aa ll ff o u r L 29 Upgrade Main Substations (Bulk Electricity supply) id ! u r e 53 30 (n/a) Rural Water Supply (15 boreholes) lb e 32 (n/a) Provision of VIP's rg 1:320 000 35 Develop Storm Water Master Plan N N 19! 38 Sewer Reticulation & Maintenance L B B R 39 Sewer Reticulation 700 H/H Ext. -

Or Tambo International

KEMPTON POMONA PARK OFFRA From ATNS head office from Hulley Rd take a left into Andre Greyvenstein Rd. M45 BENONI Carry on straight, past Mastercars & Nissan (R23) ALLEN until it turns into Albatross Rd. On Albatross Road. Keep to the left. AVION PARK Pass Boundary Silk Bazaar on left at robot. SHOPRITE R21 CHECKERS Take slip road M45 R23 Benoni, Allen Grove after overpass, keep left when turning. Turn into slip road (M43 Atlas Rd M45 Benoni). ALBATROSS RD (BRIDGE) M43 ATLAS RD Swing around into Atlas Road and M45 BENONI VOORTREKKER take a right at next robot into Bonaero Drive. M32 M32 RHODESFIELD POMONA LUGVRAG/AIRFREIGHT M43 ATLAS RD BENONI OFFRAMP (M45) On Albatross Road. Keep to the left. VOORTREKKER TURN-OFF Pass Boundary Silk Bazaar on left at robot. Take slip road M45 R23 Benoni, Allen Grove after overpass, keep left when turning. Turn into slip road (M43 Atlas Rd M45 Benoni). Swing around into Atlas Road and take a right at next robot into Bonaero Drive. On R21 highway going north. ISANDO Take M43 Atlas Rd turnoff at first robot turn right HEAD OFFICE STERCARS R21 I SAN into Bonaero Drive. MA N S (011) 961-0100 BONAERO SAFAIR PARK HOLIDAY INN On R21 highway going south. SIM GARDEN L L RD Y Take M43 Atlas Rd turnoff HU HU LE ANDRE GREYVENSTEIN RD at first robot turn right JOHANNESBURG into Bonaero Drive. Via Barbara Rd R24 R2 R21 JHB INTER. AIRPORT BOKSBURG On R21 highway going south. KEMPTON PARK LL Take M43 Atlas Rd turnoff INTERCHANGE A AVIATION TRAINING SBURGM ACADEMY at first robot turn right AIR TRAFFIC BOK into Bonaero Drive. -

Waterside Brochure

E F F O R T L E S S L Y S E R E N E 2 Bed 1 Bath & 2 Bed 2 Bath Apartments From R 835 000 Bond and Transfer Costs Included Set opposite Bullfrog Pan, one of the most attractive natural pans in the area. Waterside offers an ideal location in the heart of Rynfield for modern secure urban living. Waterside brings to you a lifestyle where evening strolls, weekend picnics and outdoor living are available to you on your doorstep. R23 BENONI NORTH AH N M45 RYNFIELD AH M45 L O C A T I O N R23 NORTHVILLA GOEDEBURG BRENTWOOD M45 172 President Brand Rd, Rynfield, Benoni President Brand Rd OR Tambo Airport (12 km) N12 Highway (5 km) Emergencies: Linmed Hospital (2 km) Glynwood Hospital (7 km) R23 KLEINFONTEIN AH Entertainment/Retail: Lakeside Mall (6 km) Northmead Square Shopping Centre (3 km) Oakfields Shopping Centre (1 km) Schools: St Dunstans College (1 km) FERRARMERE Laerskool Rynfield (1 km) GARDENS NORTHMEAD Arbor Primary School (2 km) Laerskool Northmead (6 km) M45 M44 R23 F E A T U R E S • Spacious, Modern Apartments • Access Controlled 24/7 Security • Covered Parkings • Quality Finishes • Energy Efficient Building Methods • Ideal Location • Private Pet Friendly Gardens • Secure Urban Living • Securing Deposits from R10 000 • Bond Registration and Transfer Costs Included N PRESIDENT BRAND RD 1 2 3 4 BLOCK 1 9 10 11 12 5 8 6 7 BLOCK 2 13 16 14 15 17 18 19 20 25 26 27 28 BLOCK 3 BLOCK 4 21 24 29 32 22 23 30 31 33 34 35 36 41 42 43 44 BLOCK 5 BLOCK 6 37 40 45 48 38 39 46 47 S I T E D E V E L O P E M E N T P L A N 50 51 58 59 49 52 57 60 BLOCK 7 BLOCK 8 53 56 61 64 The development consists of 80 Two Bedroom Apartments, 54 55 62 63 with all ground floor units offering private pet friendly gardens. -

Table of Contents

GERT SIBANDE DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY FINAL IDP 2011/12 TO 2013/14 A DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY STRIVING TO EXCEL IN GOOD GOVERNANCE AND QUALITY INFRASTRUCTURE Gert Sibande District Municipality i Foreword by the Executive Mayor It gives me great pleasure to present the Draft Integrated Development Plan for the 2011/12 to 2013/14 Financial Years, in the last year of this Current Term of Office. In reviewing our 2010/11 IDP and subsequently drafting our IDP and Budget respectively for 2011/12 to 2013/14 and beyond, we have consulted quite extensively with our communities in all our constituent Local Municipalities through their varying groupings using our IDP Representative Forum and other IGR structures institutionalised within our Municipality. Culminating from the state of the Nation and state of the Province Addresses respectively, and aforementioned consultation and engagements with varying stakeholders the following Key Development objectives were identified as pertinent in bringing about improved quality of life for our entire populace:- Facilitate creation of more jobs and descent work; Form strategic partnerships in fighting hunger and poverty; Advocate for access to quality education for all our citizens; Ensure proper health care for all our communities; Ensure sustainable development of all rural communities within our jurisdictional area; Harness the building of safer and secure communities To date resounding success has been realised in number of areas, where many of our people are living decent lives as a result of the services provided by the District in collaboration with its social partners. Whilst much has been achieved, there is still much that needs to be done to reverse and ultimately eradicate undesired consequences of underdevelopment, inequality, unemployment, HIV/AIDS and poverty. -

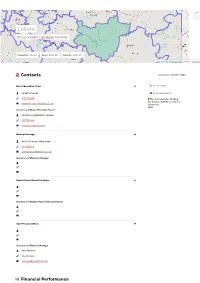

Contacts Financial Performance

+ - Lekwa B3 local municipality in Gert Sibande, Mpumalanga Population: 115 661 Size: 4 564.9 km² Density: 25.3 / km² Leaflet | Map data © OpenStreetMap contributors, CC-BY-SA Contacts Last updated October 2020 Mayor/Executive Mayor 017 712 9600 Mr LBR Dhlamini Email municipality 017 712 9634 Main Administration Building Cnr B Naude & M Maiyela Street [email protected] Standerton 2430 Secretary of Mayor/Executive Mayor Ms Precious Nonhlanhla Ngcobo 017 712 9635 [email protected] Municipal Manager Ms G P Mhlongo-Ntshangase 017 712 9613 [email protected] Secretary of Municipal Manager Deputy Mayor/Executive Mayor Secretary of Deputy Mayor/Executive Mayor Chief Financial O{cer Secretary of Financial Manager Mrs I Edwards 017 712 9613 [email protected] Financial Performance Audit Outcomes 2018-2019 2017-2018 2016-2017 2015-2016 Disclaimer of opinion Quali}ed Unquali}ed - Emphasis of Unquali}ed - Emphasis of Matter items Matter items No report available Read report Read report Read report What do dizerent audit outcomes mean? Unquali}ed Opinion Unquali}ed Opinion No Findings Emphasis of Matter Items Same as an Unquali}ed Opinion with no }ndings, but the Same as an Unquali}ed Opinion with no }ndings, but the Auditor-General wants to bring something particular to the Auditor-General wants to bring something particular to the attention of the reader. attention of the reader. Quali}ed Opinion Adverse Opinion The Auditor-General expresses reservations about the fair This is expressed when the auditor concludes that the annual presentation of the }nancial statements. There is some }nancial statements do not present the municipality’s }nancial departure from the Generally Recognised Accounting Practices position, results of operations and cash ~ows in line with (GRAP) but is not su{ciently serious as to warrant an adverse Generally Recognised Accounting Practices (GRAP). -

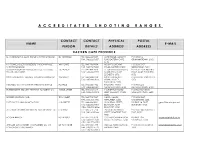

Accreditated Shooting Ranges

A C C R E D I T A T E D S H O O T I N G R A N G E S CONTACT CONTACT PHYSICAL POSTAL NAME E-MAIL PERSON DETAILS ADDRESS ADDRESS EASTERN CAPE PROVINCE D J SURRIDGE T/A ALOE RIDGE SHOOTING RANGE DJ SURRIDGE TEL: 046 622 9687 ALOE RIDGE MANLEY'S P O BOX 12, FAX: 046 622 9687 FLAT, EASTERN CAPE, GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 6140 K V PEINKE (SOLE PROPRIETOR) T/A BONNYVALE WK PEINKE TEL: 043 736 9334 MOUNT COKE KWT P O BOX 5157, SHOOTING RANGE FAX: 043 736 9688 ROAD, EASTERN CAPE GREENFIELDS, 5201 TOMMY BOSCH AND ASSOCIATES CC T/A LOCK, T C BOSCH TEL: 041 484 7818 51 GRAHAMSTAD ROAD, P O BOX 2564, NOORD STOCK AND BARREL FAX: 041 484 7719 NORTH END, PORT EINDE, PORT ELIZABETH, ELIZABETH, 6056 6056 SWALLOW KRANTZ FIREARM TRAINING CENTRE CC WH SCOTT TEL: 045 848 0104 SWALLOW KRANTZ P O BOX 80, TARKASTAD, FAX: 045 848 0103 SPRING VALLEY, 5370 TARKASTAD, 5370 MECHLEC CC T/A OUTSPAN SHOOTING RANGE PL BAILIE TEL: 046 636 1442 BALCRAIG FARM, P O BOX 223, FAX: 046 636 1442 GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 BUTTERWORTH SECURITY TRAINING ACADEMY CC WB DE JAGER TEL: 043 642 1614 146 BUFFALO ROAD, P O BOX 867, KING FAX: 043 642 3313 KING WILLIAM'S TOWN, WILLIAM'S TOWN, 5600 5600 BORDER HUNTING CLUB TE SCHMIDT TEL: 043 703 7847 NAVEL VALLEY, P O BOX 3047, FAX: 043 703 7905 NEWLANDS, 5206 CAMBRIDGE, 5206 EAST CAPE PLAINS GAME SAFARIS J G GREEFF TEL: 046 684 0801 20 DURBAN STREET, PO BOX 16, FORT [email protected] FAX: 046 684 0801 BEAUFORT, FORT BEAUFORT, 5720 CELL: 082 925 4526 BEAUFORT, 5720 ALL ARMS FIREARM ASSESSMENT AND TRAINING CC F MARAIS TEL: 082 571 5714 -

Government Notice No

STAATSKOERANT, 10 FEBRUARIE 2006 ~0.28458 7 GOVERNMENT NOTICES GOEWERMENTSKENNISGEWINGS DEPARTMENT OF ARTS AND CULTURE DEPARTEMENT VAN KUNS EN KULTUUR No. 113 10 February 2006 APPROVAL OF OFFICIAL PLACE NAMES I, Z, Pallo Jordan, Minister of Arts and Culture officially approved the following place names on the advice of the South African Geographical Names Council on 11 November 2005. Dibaba (change of name from Diepgezet) A settlement IO km W of Carolina in Mpumalanga Ekhandizwe (change of name from Louis A settlement 65 km S of Globlersdal Creek) in Mpumalanga eKulindeni A settlement 20 km S of Badplaas in Mpumalanga eMalahleni (change of name from Witbank) A settlement in Witbank CBD in Mpumalanga Umfazezala (correction of spelling from A river 9 km S of Umdoni uM fazaza na) Municipality in KZN Emfazezala (correction of spelling from A village 9 krn S of Urndoni eMfazazana) municipality in Mpumalanga eMpangeleni (change of name from A settlement in Standerton in Boesmanskraal) Mpumalanga eMpuluzi A river 85 km W of Carolina in Mpumalanga eMthenteni (correction of spelling from A town 9 km N of Hibiscus District elllltentweni) Municipality in KwaZulu-Natal 8 No. 28458 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 10 FEBRUARY 2006 eMuziwezinto A town 8 km W of uMdoni (correction of spelling from Emuziwezinto) Municipality in KwaZulu-Natal Umuziwezinto (correction of spelling from A river 8 km W of uMdoni uMuziwezinto) Municipality in KwaZulu-Natal Engodtomezi (change of name from Syde) A mountain 86 km W of Carolina in Mpumalanga eSilobela A township 1 km W of