REVIEWS January 2016 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OBSERVER Vol

OBSERVER Vol. 7 No. 1 September 20, 1996 Page 1 Furor at the Forum Jeanne Swadosh Page 2 Student Rally Congregates on Leon’s Lawn Sean O’Neill Tenure Anna-Rose Mathieson and Nathan Reich Page 3 Flik Has Arrived Julilly Kohler-Hausmann and Betsy Norlander Notebook Sean O’Neill Page 4 Bard College Convocation Fund Budget ASO Budget Proposal [African Student Organization] Page 5 Election for the Representatives to the Board of Trustees Page 6 Voter Registration Procedure Causes Stir Jeanne Swadosh Student Judiciary Board Guidelines Page 7 Questionnaire Incited Controversy [Voter Registration] Page 8 Case Closed on Open Container Stephanie Schneider Facts and History of the Alcohol Policy Sean O’Neill Page 9 The Faces of Security Page 10 The Bard Sports Report Chris Van Dkye Bulletproof Riddled With Plot Holes Abigail Rosenberg Page 11 Gastr del Sol Shines on New Release Joel Hunt Page 12 Our Voices Are Not Being Heard Page 13 Alcohol and the Age Law: What’s the Message Eli Andrews Uh, Houston, We Have a Problem Meredith Yayanos Page 14 Mass Demagoguery and the Bard Body Politic Page 15 A Comment on No Comment Shawnee Barnes The Somnambulist It’s not all here in black and white Page 16 Bagatelle for a Bug Charlotte Jaskson Observer Editorial Policy Page 17 News From Nicaragua Page 18 A Vote for the Selfish Jeremy Dillahunt What’s Planned for Student Activities "This time , we mean lt.. " Student RaLLy, page 2 Flil<, page 3 Voter Registration, page 7 Alcohol Policy, page 8 ......,. E intnent . .__ _, __ . -

Feature Film Project Summary Logline Synopsis

HERE Feature Film Project Summary A Braden King Film Written by Braden King and Dani Valent Producers: Lars Knudsen, Jay Van Hoy Co-Producer: Jeff Kalousdian Executive Producers: Zoe Kevork, Julia King A Truckstop Media / Parts and Labor Production 302A W. 12th St., #223 New York, New York 10014 (212) 989-7105 / [email protected] www.herefilm.info Logline HERE is a dramatic, landscape-obsessed road movie that chronicles a brief but intense romantic relationship between an American satellite-mapping engineer and an expatriate Armenian art photographer who impulsively decide to travel together into uncharted territory. Synopsis Will Shepard is an American satellite-mapping engineer contracted to create a new, more accurate survey of the country of Armenia. Within the industry, his solitary work - land-surveying satellite images to check for accuracy and resolve anomalies - is called “ground-truthing”. He’s been doing it on his own, for years, all over the world. But on this trip, his measurements are not adding up. Will meets Gadarine Najarian at a rural hotel. Tough and intriguing, she’s an expatriate Armenian art photographer on her first trip back in ages, passionately trying to figure out what kind of relationship - if any - she still has with her home country and culture. Fiercely independent, Gadarine is struggling to resolve the life she’s led abroad with the Armenian roots that run so deeply through her. There is an instant, unconscious bond between these two lone travelers; they impulsively decide to continue together. HERE tells the story of their unique journey and the dramatic personal transformations it leads each of them through. -

PRESS RELEASE Contact: Whitney Museum of American Art Stephen

PRESS RELEASE Contact: Whitney Museum of American Art Stephen Soba, Meghan Bullock, Nathan Davis (212) 570-3633 November 2003 AN EXPANDED LINE-UP OF PERFORMANCES FOR WHITNEY’S FRIDAY-EVENING SOUNDCHECK SERIES DURING 2004 BIENNIAL The Whitney’s SoundCheck series – an occasion for crowds to gather at the Museum from 6 to 9 pm on select Friday evenings, when the Museum’s atmosphere shifts into a more relaxed mode, and admission is pay-what-you-wish – will feature an expanded line-up of events during the 2004 Biennial. All the evenings throughout the run of the 2004 Biennial highlight Biennial artists in performance. At a moment of profound change in our cultural landscape, the 2004 Biennial will explore the latest aesthetic tendencies in works reflecting a reinvigoration of contemporary American art by 108 American artists and collaborative teams. The Biennial will be on view at the Whitney Museum of American Art from March 11 to May 30. Information on performances, film and video screenings, public programs, and the Biennial as a whole is available in the Biennial program guide or online at www.whitney.org. Started during the 2002 Biennial and taking place on select Friday evenings throughout the year, the innovative SoundCheck series brings art and music together at the Whitney. Originated and organized by Debra Singer, one of the Biennial’s three curators and associate curator of contemporary art at the Whitney, SoundCheck unites artists and musicians to perform and play music at the Museum, sometimes featuring readings from some of the literary world’s rising stars. * * * 2004 BIENNIAL SOUNDCHECK PERFORMANCES Friday, March 12 at 7 pm DJ Dave Muller and Los Super Elegantes Visual artist Dave Muller will be DJ for the evening, offering a blend of musical genres that range from reggae to electronica, rock 'n' roll to house, especially focusing on underappreciated, should-have-been-a-classic songs. -

A Lengthwise Slash David Grubbs, 2011 I First Met Arnold Dreyblatt In

A Lengthwise Slash David Grubbs, 2011 I first met Arnold Dreyblatt in 1996 when he came to Chicago at Jim O’Rourke’s urging. At the time Jim and I were the two core members of the group Gastr del Sol, and we also co-directed the Dexter’s Cigar reissue label for Drag City. The basic idea of Dexter’s Cigar was that there were any number of out-of-print, underappreciated recordings that, if heard, would put contemporary practitioners to shame. Just try to stack your solo free-improv guitar playing versus Derek Bailey’s Aida. Think your power electronics group is hot? Care to take a listen to Merzbow’s Rainbow Electronics 2? Do you fancy a shotgun marriage of critical theory and ramshackle d.i.y. pop? But you’ve never heard the Red Krayola and Art and Language’s Corrected Slogans? Gastr del Sol work time was as often as not spent sharing new discoveries and musical passions. Jim and I both flipped to Dreyblatt’s 1995 Animal Magnetism (Tzadik; which Jim nicely described “as if the Dirty Dozen Brass Band got a hold of some of Arnold’s records and decided to give it a go”) as well as his ingenious 1982 album Nodal Excitation (India Navigation), with its menagerie of adapted and homemade instruments (midget upright pianoforte, portable pipe organ, double bass strung with steel wire, and so on). We knew upon a first listen that we were obliged to reissue Nodal Excitation. The next time that Arnold blew through town, we had him headline a Dexter’s Cigar show at the rock club Lounge Ax. -

BEAUTIFUL NOISE Directions in Electronic Music

BEAUTIFUL NOISE Directions in Electronic Music www.ele-mental.org/beautifulnoise/ A WORK IN PROGRESS (3rd rev., Oct 2003) Comments to [email protected] 1 A Few Antecedents The Age of Inventions The 1800s produce a whole series of inventions that set the stage for the creation of electronic music, including the telegraph (1839), the telephone (1876), the phonograph (1877), and many others. Many of the early electronic instruments come about by accident: Elisha Gray’s ‘musical telegraph’ (1876) is an extension of his research into telephone technology; William Du Bois Duddell’s ‘singing arc’ (1899) is an accidental discovery made from the sounds of electric street lights. “The musical telegraph” Elisha Gray’s interesting instrument, 1876 The Telharmonium Thaddeus Cahill's telharmonium (aka the dynamophone) is the most important of the early electronic instruments. Its first public performance is given in Massachusetts in 1906. It is later moved to NYC in the hopes of providing soothing electronic music to area homes, restaurants, and theatres. However, the enormous size, cost, and weight of the instrument (it weighed 200 tons and occupied an entire warehouse), not to mention its interference of local phone service, ensure the telharmonium’s swift demise. Telharmonic Hall No recordings of the instrument survive, but some of Cahill’s 200-ton experiment in canned music, ca. 1910 its principles are later incorporated into the Hammond organ. More importantly, Cahill’s idea of ‘canned music,’ later taken up by Muzak in the 1960s and more recent cable-style systems, is now an inescapable feature of the contemporary landscape. -

Lasse Marhaug & Incapacitants Music Writing

nyMusikk vårprogram 2015 nyMusikk + All Ears nyMusikk + Borealis 9. januar Lasse Marhaug & 9. mars Borealis preview To høydepunkter fra programmet til årets Incapacitants Borealisfestival: Den eksperimentelle Støypioner Marhaug i samtale med den trubaduren Richard Dawson + cellovirtuosen ikoniske japanske støyduoen Incapacitants. Oliver Coates med Chrysanthemum Bear. nyMusikk kl. 14:00. Gratis, lett servering. Blå kl. 20:00. Kr 150 / 100 (medl.) nyMusikk + Big Bang 23. januar Music writing masterclass 10. – 11. april Musikkmagasinet The Wire holder skrivekurs nyMusikk Kids: i musikkjournalistikk og musikkritikk. Påmelding: [email protected]. Stavanger Konserthus Kunstnernes Hus kl. 11:00-16:00. iPad-workshop for barn 6 - 12 år som del av den Kr 350/250 (stud.) europeiske barnemusikkfestivalen Big Bang. Program: stavanger-konserthus.no 23. januar David Grubbs nyMusikk + Henie Onstad Kunstsenter Off The Page kick-off solokonsert med grunnleggeren av Squirrel Bait, Bastro og Lene Grenager på HOK: Gastr del Sol. The Wire Sound System DJs. Last Train kl. 22:00. Kr 100/gratis (medl.) 10. mai Ensemble Zwischentöne Konsertdag i forbindelse med Melgaard/ Rickhard-utstillingen. Et av verdens fremste nyMusikk + The Wire 24. januar samtidsmusikkensembler, Ensemble Off The Page Oslo Zwischentöne, urfremfører et nytt verk av Musikkfestival uten musikk: Samtaler, foredrag, Lene Grenager. Jon Wesseltoft-solo i performance, film og musikkmarked. Melgaard-utstillingen. Kunstnernes Hus kl. 11: 00 – 22:00. Kr 250 / 150 Henie Onstad Kunstsenter kl. 14.00. Kr 80/50. 1. februar nyMusikk Kids: Ilios Only Connect iPad-workshop for barn 6 - 12 år med slagverker 4. – 7. juni Eirik Raude. Påmelding til [email protected]. Festival Of Sound Galleri NordNorge, Harstad kl. -

Salem Leaving Takoma Park

Salem Leaving Takoma Park ~ 43 Years of John Fahey ~ The John Fahey Catalog From The International Fahey Committee Chris Downes, Paul Bryant, Malcolm Kirton, Tom Kremer Thanks to Mitchell Wittenberg and Glenn Jones DISCOGRAPHY...................................................................................................................................................... 4 SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................................................. 4 TRACK LISTING...................................................................................................................................................... 6 THE FONOTONE SESSIONS 1958-1962 ............................................................................................................... 6 BLIND JOE DEATH 1959/1964/1967 ..................................................................................................................... 8 DEATH CHANTS, BREAKDOWNS, AND MILITARY WALTZES 1964/1967........................................................ 8 THE DANCE OF DEATH AND OTHER PLANTATION FAVORITES 1964/67 .................................................... 9 THE TRANSFIGURATION OF BLIND JOE DEATH 1965 ................................................................................... 9 THE EARLY YEARS (FONOTONE) 1965 ............................................................................................................ 10 GUITAR VOLUME 4 THE GREAT SAN BERNARDINO BIRTHDAY -

The History of Rock Music - the Nineties

The History of Rock Music - The Nineties The History of Rock Music: 1995-2001 Drum'n'bass, trip-hop, glitch music History of Rock Music | 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-75 | 1976-89 | The early 1990s | The late 1990s | The 2000s | Alpha index Musicians of 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-76 | 1977-89 | 1990s in the US | 1990s outside the US | 2000s Back to the main Music page (Copyright © 2009 Piero Scaruffi) Post-post-rock (These are excerpts from my book "A History of Rock and Dance Music") The Louisville alumni 1995-97 TM, ®, Copyright © 2005 Piero Scaruffi All rights reserved. The Squirrel Bait and Rodan genealogies continued to dominate Kentucky's and Chicago's post-rock scene during the 1990s. Half of Rodan, i.e. Tara Jane O'Neil (now on vocals and guitar) and Kevin Coultas, formed Sonora Pine with keyboardist and guitarist Sean Meadows, violinist Samara Lubelski and pianist Rachel Grimes. Their debut album, Sonora Pine (1996), basically applied Rodan's aesthetics to the format of the folk lullaby. Another member of Rodan, guitarist Jeff Mueller, formed June Of 44 (11), a sort of supergroup comprising Sonora Pine's guitarist Sean Meadows, Codeine's drummer and keyboardist Doug Scharin, and bassist and trumpet player Fred Erskine. Engine Takes To The Water (1995) signaled the evolution of "slo-core" towards a coldly neurotic form, which achieved a hypnotic and catatonic tone, besides a classic austerity, on the mini-album Tropics And Meridians (1996). Sustained by abrasive and inconclusive guitar doodling, mutant rhythm and off-key counterpoint of violin and trumpet, Four Great Points (1998) metabolized dub, raga, jazz, pop in a theater of calculated gestures. -

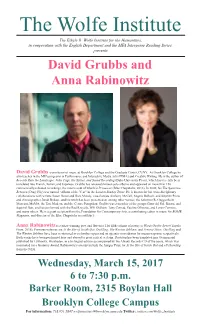

The Wolfe Institute the Ethyle R

The Wolfe Institute The Ethyle R. Wolfe Institute for the Humanities, in cooperation with the English Department and the MFA Intergenre Reading Series, presents David Grubbs and Anna Rabinowitz David Grubbs is professor of music at Brooklyn College and the Graduate Center, CUNY. At Brooklyn College he also teaches in the MFA programs in Performance and Interactive Media Arts (PIMA) and Creative Writing. He is the author of Records Ruin the Landscape: John Cage, the Sixties, and Sound Recording (Duke University Press), which has recently been translated into French, Italian, and Japanese. Grubbs has released thirteen solo albums and appeared on more than 150 commercially-released recordings, the most recent of which is Prismrose (Blue Chopsticks, 2016). In 2000, his The Spectrum Between (Drag City) was named “Album of the Year” in the London Sunday Times. He is known for his cross-disciplinary collaborations with writers Susan Howe and Rick Moody, visual artists Anthony McCall, Angela Bulloch, and Stephen Prina, and choreographer Jonah Bokaer, and his work has been presented at, among other venues, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, MoMA, the Tate Modern, and the Centre Pompidou. Grubbs was a member of the groups Gastr del Sol, Bastro, and Squirrel Bait, and has performed with the Red Krayola, Will Oldham, Tony Conrad, Pauline Oliveros, and Loren Connors, and many others. He is a grant recipient from the Foundation for Contemporary Arts, a contributing editor in music for BOMB Magazine, and director of the Blue Chopsticks record label. Anna Rabinowitz is a prize-winning poet and librettist. Her fifth volume of poetry isWords On the Street (Tupelo Press, 2016). -

Slints Spiderland Free

FREE SLINTS SPIDERLAND PDF Scott Tennent | 144 pages | 30 Dec 2010 | Continuum Publishing Corporation | 9781441170262 | English | New York, United States Slint - Spiderland (, Vinyl) | Discogs Slint's landmark second album has been reissued in a box set that includes outtakes, live cuts, and a feature-length documentary by Lance Bangs. The record's greatest Slints Spiderland might be the boundless inspiration it perpetually provides for all the bands that have yet to emerge from the basement. And just what did Slint think their audience—who, judging from the faint smattering of applause, barely cracked the double digits— needed to hear at that moment? In many respects, the story Slints Spiderland Slint is an exceedingly familiar one of influence accruing in absentia, of mavericks who were ignored in their time and had to wait years to get their due. Through their initial existence, Slint were obscure Slints Spiderland even within the subterranean confines of the American indie-rock underground. Compared to the get-in-the-van, play-anywhere ethic practised by fellow s-hardcore students, Slint rarely performed live, and when they did, it was rarely as a headliner. Slints Spiderland were scarce; band photos all the more so. And with the similarly atmospheric, equally explosive likes of Mogwai and Godspeed You! Black Emperor dominating the lates indie-rock conversation, Slint ceased to be just some band that had broken up too soon and became an entire subgenre of Slints Spiderland unto itself. I mean, just look at the cover of the Slints Spiderland set—notice something missing? The demos practically break down Spiderland on a riff-by-riff basis, as we hear the songs devolve from pre-production dress rehearsals to rudimentary acoustic sketches recorded on cassette. -

Excerpts from What the Press Has Said About

Excerpts from what the press has said about some of Cheer-Accident’s past releases: WHAT SEQUEL? 2006 PRAVDA Featuring: Scott Ashley (Guitar), Thymme Jones (Vocals, Drums, Clarinet, Trumpet, Recorder, various keyboard instruments), Jeff Libersher (Bass, Guitar, Piano, Trumpet, bg. Vocals), John McEntire (Overdubs, Mixing), Julie Pomerleau (Violin), Jessica Ruffins (Engineer), Toby Summerfield (Double Bass) “Cheer-Accident seems to thrive on the contradictions of experimental music. For every straight-ahead piano-driven pop number there's a song flailing hard rock riffs with abandon, and usually these two opposing genres are place right next to one another. …the group does an admirable job synthesizing an avant-garde pop collection from decades old indie rock basics and eccentric asides. There are shades of Pavement, Unwound and Sonic Youth in the slightly atonal slacker guitar strum on "Keep in Touch," the pogoing chorus punctuation seems particularly Malkmus-ian. "Go Gone Green" has a great drive of '70s prog/jazz... Jesus Lizard skronk spreads out all over "Surviving a Methodology;" chugging guitars cut a sinister path through a rhythm section bent on strange time signatures. …as an album of '90s fringe indie rock revisited, it's a fine statement.” – Aaron Shaul, Ink 19, July 2007, www.ink19.com “… Cheer-Accident has been dirtying their hands in some form or another for over twenty-years and it’s obvious that music is the fruit of their hard work. … What Sequel? finds the band actually introducing the word “concise” into their terminology, thanks in large part to the efforts of producer John McEntire (Tortoise, The Sea And Cake). -

Paul Weller Wild Wood

The Venus Trail •Flying Nun-Merge Paul Weller Wild Wood PAUL WELLER Wild Wood •Go! Discs/London-PLG FAY DRIVE LIKE JEHU Yank Crime •Cargo-Interscope FRENTE! Marvin The Album •Mammoth-Atlantic VOL. 38 NO.7 • ISSUE #378 VNIJ! P. COMBUSTIBLE EDISON MT RI Clnlr SURE THING! MESSIAH INSIDE II The Grays On Page 3 I Ah -So-Me-Chat In Reggae Route ai DON'T WANT IT. IDON'T NEED IT. BUT ICAN'T STOP MYSELF." ON TOUR VITH OEPECHE MOUE MP.'i 12 SACRAMENTO, CA MAJ 14 MOUNTAIN VIEV, CA MAI' 15 CONCORD, CA MA,' 17 LAS, VEGAS, NV MAI' 18 PHOENIX, AZ Aff.q 20 LAGUNA HILLS, CA MAI 21 SAN BERNARDINO, CA MA,' 24 SALT LAKE CITY, UT NOTHING MA,' 26 ENGLEVOOD, CO MA,' 28 DONNER SPRINGS, KS MA.,' 29 ST. LOUIS, MO MP, 31 Sa ANTONIO, TX JUNE 1HOUSTON. TX JUNE 3 DALLAS, TX JUNE 5BILOXI, MS JUNE 8CHARLOTTE, NC JUNE 9ATLANTA, GA THE DEBUT TRACK ON COLUMBIA .FROM THE ALBUM "UNGOD ." JUNE 11 TILE ,' PARX, IL PROOUCED 81.10101 FRYER. REN MANAGEMENT- SIEVE RENNIE& LARRY TOLL. COLI MI-31% t.4t.,• • e I The Grays (left to right): Jon Brion, Jason Falkner, Dan McCarroll and Buddy Judge age 3... GRAYS On The Move The two started jamming together, along with the band's third songwriter two guys who swore they'd never be in aband again, Jason Falkner and Buddy Judge and drummer Dan McCarron. The result is Ro Sham Bo Jo Brion sure looked like they were having agreat time being in the Grays (Epic), arecord full of glorious, melodic tracks that owe as much to gritty at BGB's earlier this month.