Founddirdisstudents00bryarich.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![THE WARMWATER STREA]US SYNTPOSIUM a National Symposium on Fisheries Aspects of Warmwater Streams](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7928/the-warmwater-strea-us-syntposium-a-national-symposium-on-fisheries-aspects-of-warmwater-streams-327928.webp)

THE WARMWATER STREA]US SYNTPOSIUM a National Symposium on Fisheries Aspects of Warmwater Streams

THE WARMWATER STREA]US SYNTPOSIUM A National Symposium on Fisheries Aspects of Warmwater Streams LOUIS A. KRUMHOLZ Editor Crrenr-Bs F. Bnyam, GonooN E. HnLr-, GeRr-eNo B. Penour Associate Editors PnocBnorNGS oF e Syuposrulr Hnro AT THE UurvBnsrry or TeNxnssen, KNoxtlt lr Kloxvrrr-o, TrNNessrE 9-II March Ig80 Southern Division American Fisheries Societv WARMWATHSTREAMS SYMPOSIUM THE WARMWATER STRtrAMS SYMPOSIUM S A National Syrnposium on Fisheries Aspects of Warmwater Streams LOUIS A. KRUN,IHOLZ Editor Cu.rrups F. Bnv,rx. Conoox E. Ihr,r-. G.rrrr,,rxu B. Prru>uu A.s.s o r : i t t t t, li d it o r.s PnocnBulxcs oF .r Syrtposturr Hrilr> AT THl.l Ul.lrl,rtrstrv rtr TrxrpssuE. Ktoxt,lLLg KxoxvrLLs. Ttxr,lnssse 9-11 \larch 1980 Southenr Division Anerictrn Fisheries Societr THE WARMWATER STREAMS SYMPOSIUM Srnenrxc Cornrrrrps Melvin T. Huish, Chairman W. Donalcl Baker Allen A. Forshage Wendell J. Lorio Charles F. Bryar-r Ronnie J. Gilbert Barry Lyons Tohn Cloud Amold J. Herring Paul E. Mauck David T. Cox Daniel R. Holder Robert E. Miles Daniel W. Crochet Ben D. Jaco Anthony W. Mullis Edrvin E. Crowell Tohn W. Kaufmann Garland B. Pardue Gladney Duvidson Charles J. Killebrew Monte E. Seehorn Robert M. Drrvis Jar.nes Little Agustin Valido J. Phillip Edwarcls Clarence E. White, Jr. Spoxsons Publication o[ these Proceedings u'irs aided by grirnts liom the Bass Anglers Sportsnan Society National Science Foundation Bass Research Foundartion Sport Fishing Institute Carolina Power and Light Company U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Duke Power Comptury U.S. -

TELEVISION NOMINEES DRAMA SERIES Breaking Bad, Written By

TELEVISION NOMINEES DRAMA SERIES Breaking Bad, Written by Sam Catlin, Vince Gilligan, Peter Gould, Gennifer Hutchison, George Mastras, Thomas Schnauz, Moira Walley-Beckett; AMC The Good Wife, Written by Meredith Averill, Leonard Dick, Keith Eisner, Jacqueline Hoyt, Ted Humphrey, Michelle King, Robert King, Erica Shelton Kodish, Matthew Montoya, J.C. Nolan, Luke Schelhaas, Nichelle Tramble Spellman, Craig Turk, Julie Wolfe; CBS Homeland, Written by Henry Bromell, William E. Bromell, Alexander Cary, Alex Gansa, Howard Gordon, Barbara Hall, Patrick Harbinson, Chip Johannessen, Meredith Stiehm, Charlotte Stoudt, James Yoshimura; Showtime House Of Cards, Written by Kate Barnow, Rick Cleveland, Sam R. Forman, Gina Gionfriddo, Keith Huff, Sarah Treem, Beau Willimon; Netflix Mad Men, Written by Lisa Albert, Semi Chellas, Jason Grote, Jonathan Igla, Andre Jacquemetton, Maria Jacquemetton, Janet Leahy, Erin Levy, Michael Saltzman, Tom Smuts, Matthew Weiner, Carly Wray; AMC COMEDY SERIES 30 Rock, Written by Jack Burditt, Robert Carlock, Tom Ceraulo, Luke Del Tredici, Tina Fey, Lang Fisher, Matt Hubbard, Colleen McGuinness, Sam Means, Dylan Morgan, Nina Pedrad, Josh Siegal, Tracey Wigfield; NBC Modern Family, Written by Paul Corrigan, Bianca Douglas, Megan Ganz, Abraham Higginbotham, Ben Karlin, Elaine Ko, Steven Levitan, Christopher Lloyd, Dan O’Shannon, Jeffrey Richman, Audra Sielaff, Emily Spivey, Brad Walsh, Bill Wrubel, Danny Zuker; ABC Parks And Recreation, Written by Megan Amram, Donick Cary, Greg Daniels, Nate DiMeo, Emma Fletcher, Rachna -

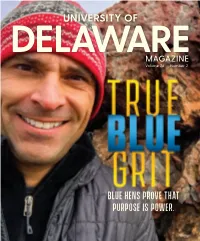

Udmagazine V26n2.Pdf

UNIVERSITY OF UNIVERSITY OF DELAWARE MAGAZINE • VOLUME 26, NUMBER 2 • SEPTEMBER 2018 2018 SEPTEMBER • 2 NUMBER 26, VOLUME • MAGAZINE OF DELAWARE UNIVERSITY DELAWAREMAGAZINE Volume 26 • Number 2 Blue Hens prove that purpose is power. BLUE HEN FOOTBALL KICKS OFF THE NEW SEASON 2 University of Delaware Magazine DUANE PERRY DUANE Volume 26 Number 2 2018 1 VOL. 26 CONTENTSNo. 2 FEATURES THE POWER OF PURPOSE 14 In her work to help survivors of domestic violence, Christina Principe, EHD96, sees echoes of her own arduous past UD’S ENDURING VOICE 22 From WHEN to WVUD, the University’s radio station has come a long way in 50 years COME WHAT MAE Meet Mae Carter, the 38 woman who changed UD for all women BY THE SKIN OF 44 HIS TEETH Before his bestseller Meg became the summer’s blockbuster, author and CAMPBELL MARK alumnus Steve Alten, HS84M, faced a rocky road to success IN EVERY ISSUE MEMORABLE MOMENTS 6 ON THE GREEN What headline-making plays will the new season bring? Nationally ranked in multiple 35 OFFICE HOURS preseason polls, how high will our Hens fly? Find out this fall as you cheer on your favorite team. 48 ALUMNI NEWS Visit bluehens.com to view the full schedule and purchase your tickets. 57 CLASS NOTES 2 University of Delaware Magazine CONTENTS UNIVERSITY OF DELAWARE MAGAZINE Volume 26, Number 2 CONTENTS THINGS TO Managing Editor Artika Rangan Casini, AS05 Associate Editor Eric Ruth, AS93 Executive Editor John Brennan Vice President for Communications & Marketing Glenn Carter Art Director & LEARN Online Production Molly Chappell FROM Contributing Design Jeffrey Chase, AS91, Christian Derr, Don Shenkle, AS80, BE17M THIS ISSUE Class Notes & Production Daniel Wright Senior Photographer Kathy F. -

DAVID HELFAND, ACE Editor

DAVID HELFAND, ACE Editor PROJECTS DIRECTORS STUDIOS/PRODUCERS YOUNG SHELDON Various Directors WARNER BROS. / CBS Seasons 1 - 5 Chuck Lorre, Steven Molaro Tim Marx UNITED WE FALL Mark Cendrowski ABC / John Amodeo, Julia Gunn Pilot Julius Sharpe UNTITLED REV RUN Don Scardino AMBLIN PARTNERS / ABC Pilot Presentation Jeremy Bronson, Rev Run Simmons Jhoni Marchinko ATYPICAL Michael Patrick Jann SONY / NETFLIX 1 Episode Robia Rashid, Seth Gordon Mary Rohlich, Joanne Toll GREAT NEWS Various Directors UNIVERSAL / NBC Season 1 Tina Fey, Robert Carlock Tracey Wigfield, David Miner THE BRINK Michael Lehman HBO / Roberto Benabib, Jay Roach Season 1 Tim Robbins Jerry Weintraub UNCLE BUCK Reggie Hudlin ABC / Brian Bradley, Steven Cragg Season 1 Ken Whittingham Korin Huggins, Will Packer Fred Goss Franco Bario BAD JUDGE Andrew Fleming NBC / Adam McKay, Kevin Messick Pilot Will Ferrell THE MINDY PROJECT Various Directors FOX / Mindy Kaling, Howard Klein Seasons 1 - 2 Michael Spiller WEEDS Craig Zisk SHOWTIME Series Paul Feig Jenji Kohan, Roberto Benabib 2x Nominated, Single Camera Comedy Paris Barclay Mark Burley Series – Emmys NEXT CALLER Pilot Marc Buckland NBC / Stephen Falk, Marc Buckland PARTY DOWN Bryan Gordon STARZ Season 2 Fred Savage John Enbom, Rob Thomas David Wain Dan Etheridge, Paul Rudd THE MIDDLE Pilot Julie Anne Robinson ABC / DeeAnn Heline, Eileen Heisler GANGSTER’S PARADISE Ralph Ziman Tendeka Matatu Winner, Best Editing, FESPACO Awards FOSTER HALL Bob Berlinger NBC / Christopher Moynihan Pilot Conan O’Brien, Tom Palmer THAT ‘70S SHOW David Trainer FOX Season 6 Jeff Filgo, Jackie Filgo, Tom Carsey Nominated, Multi-Cam Comedy Series – Mary Werner Emmys CRACKING UP Chris Weitz FOX Pilot Paul Weitz Mike White GROSSE POINTE Peyton Reed WARNER BROS. -

EUREKA Country Mile! Garages & Sheds Farming and Industrial Structures

The Moorabool News FREE Your Local News Tuesday 5 November, 2013 Serving Ballan and district since 1872 Phone 5368 1966 Fax 5368 2764 Vol 7 No 43 He’s our man! By Kate Taylor Central Ward Councillor Paul Tatchell has been voted as Moorabool’s new Mayor. East Ward Councillor John Spain was voted in as Deputy Mayor. Outgoing Mayor Pat Toohey did not re-nominate at the Statutory and Annual Appointments Meeting held last Wednesday 30 October, where Mayor Tatchell won the role with a 5-2 majority. Nominated by East Ward Councillor Allan Comrie, Cr Tatchell gained votes from fellow councillors Comrie, David Edwards, Tonia Dudzik and John Spain. West Ward Councillor Tom Sullivan was nominated and voted for by Pat Toohey. New Mayor Tatchell told the meeting he was very fortunate to have been given the privilege of the role. “For former mayor Pat Toohey, to have come on board and then taken on the role of Mayor with four new councillors, he jumped straight in the driver’s seat… and the first few months were very difficult, but he persevered with extreme patience. “And to the experienced councillors we came in contact with from day one, with years of experience, without that, I can’t imagine how a council could have operated with seven new faces. We are incredibly fortunate to have those experienced councillors on board.” Mayor Tatchell also hinted at a vision for more unity in the future. “A bit less of ‘I’ and more of ‘we,’” he said. Deputy Mayor Spain was voted in with votes from councillors Dudzik, Edwards, and Comrie, with Mayor Tatchell not required to cast a vote on a majority decision. -

The Wonder Years Episode & Music Guide

The Wonder Years Episode & Music Guide “What would you do if I sang out of tune … would you stand up and walk out on me?" 6 seasons, 115 episodes and hundreds of great songs – this is “The Wonder Years”. This Episode & Music Guide offers a comprehensive overview of all the episodes and all the songs played during the show. The episode guide is based on the first complete TWY episode guide which was originally posted in the newsgroup rec.arts.tv in 1993. It was compiled by Kirk Golding with contributions by Kit Kimes. It was in turn based on the first TWY episode guide ever put together by Jerry Boyajian and posted in the newsgroup rec.arts.tv in September 1991. Both are used with permission. The music guide is the work of many people. Shane Hill and Dawayne Melancon corrected and inserted several songs. Kyle Gittins revised the list; Matt Wilson and Arno Hautala provided several corrections. It is close to complete but there are still a few blank spots. Used with permission. Main Title & Score "With a little help from my friends" -- Joe Cocker (originally by Lennon/McCartney) Original score composed by Stewart Levin (episodes 1-6), W.G. Snuffy Walden (episodes 1-46 and 63-114), Joel McNelly (episodes 20,21) and J. Peter Robinson (episodes 47-62). Season 1 (1988) 001 1.01 The Wonder Years (Pilot) (original air date: January 31, 1988) We are first introduced to Kevin. They begin Junior High, Winnie starts wearing contacts. Wayne keeps saying Winnie is Kevin's girlfriend - he goes off in the cafe and Winnie's brother, Brian, dies in Vietnam. -

Further Action Planned on Bresler Dismissal

-- VOL. 91 NO. 21 · ·., 1 ur Ll lJNJWRSITY OF DELAWARE, NEWAR~ DELAWARE FRfDA Y, DECEMBER 6, 196~ Further Action Planned On Bresler Dismissal By MARGE PALA discuss tl:.e Bresler case with shall continue to be our SGA senators and others position unless substantive The Student Government --A series of teach-in's, reasons are given to the Association and leaders of rallies and marches, one of contrary.'" campus organizations met last them to be conducted by "Dr. Bresler's case has night to discuss and propose fraternity men on campus been reviewed and a decision further student action --Encourage all students to not to renew his contract has involving the dismissal of post-date their checks for been made. We feel that this Prof. Robert J. Bresler. second semester bills decision as well as others was Specific recommendations' --Consider a boycott or made in a manor 'inconsistent for further action were strike of classes before with sound academic scheduled to come from the Christmas recess practice.' · Moreover, meeting, which was the fifth --Consider the occupation substantive . reasons for for senate and senate of a building dismissal have not been given , committees this week. --Consider disbanding and we therefore feel that the Prefacing the SGA actions SGA if it appears that the SGA must take whatever expected to be proposed was university refuses to be a non-violent actions are a statement of position and "college which places a high necessary to secure a renewal reasons by · the SGA value in classroom of Dr. Bresler's contract. Non-Renewal Action performance, attention to "We further believe that Committee on the case of individual students and undergraduate and graduate Bresler. -

On the Shoulders of Giants: How Aaron Sorkin's Sports Night

ON THE SHOULDERS OF GIANTS: How Aaron Sorkin’s Sports Night Portrayed the Sports Journalist as a Modern, Educated Professional While Still Fitting the Classic Molds of Journalists in Popular Culture. By Eric Alvarez Abstract Aaron Sorkin’s Sports Night focuses on the events that unfold in the newsroom of a nightly sports highlight show. The impulse of the series stems from the relationships amongst the show’s two anchors, three producers and its managing editor. As individuals, the journalists are smart, talented and dedicated in their professional lives. Yet, despite their capabilities and professionalism, each echoes characteristics and faces problems similar to those of journalists in classic popular culture. They often put the job over their personal lives and struggle when faced with the consequences. But in the end, they always tend to band together as a newsroom family. * * * “Five minutes to air. First team in the studio.1” The voice echoes through the newsroom at 10:55 p.m. It is the nightly wake-up call for the Sports Night team. Journalists both in front of the camera and in the control room scramble as the clock ticks toward show time. And then it starts. The one thing that gives the journalists a home, a family and a sense of accomplishment. ON THE SHOULDERS OF GIANTS: How Aaron Sorkin’s Sports Night Portrayed the Sports Journalist as a Modern, Educated Professional While Still Fitting the Classic Molds of Journalists in Popular Culture. By Eric Alvarez 2 The team of anchors and producers creates a nightly, one-hour highlight show from New York, “the most magnificent city in the world. -

2021 FOOTBALL Preview

S1 2021 FOOTBALL Preview Featuring EAST SURRY EAST WILKES ELKIN FORBUSH MOUNT AIRY NORTH STOKES NORTH SURRY SOUTH STOKES STARMOUNT SURRY CENTRAL WEST STOKES S2 Carolina Roofing & Construction Our Family Has Been Taking Care Of Your Roofing & Home Improvement Needs Since 1934 2019 Winner NT AIR OU Y N M E E W H S T #1 & BEST MOUNTIE AWARD OF THE BEST Winner2021 What we can provide for your service needs Vinyl Siding · Paint Interior & Exterior · Seamless Gutters • Residential & Commercial Roofing Single Ply Rubber Specialist for all your Flat Roof Roofing needs Asphalt Shingles · Metal Roofing Meet Our Newest Addition Our family continues with the 5th generation PREVIEW 2021 PREVIEW Thomas Alexander Cochrane Professionalism Over Profit Since 1934 FOOTBALL 1375 South Main St | Mount Airy, NC 27030 (336) 786-1260 | carolina-roofing.business.site/ 2 70052333 S3 Things don’t always go as planned. We’re here for you. FOOTBALL PREVIEW 2021 PREVIEW FOOTBALL Choose Well. Choose Northern. ChooseNorthern.org | NorthernUrgentCare.com 3 70051907 MTAS4 We’ve Put Together MOUNT AIRY Another Winning Team At BEARS We Wish All Area Teams Good Luck on This Season! PILOT MOUNTAIN GUNS & AMMO Buy, Sell, Trade! Class 3 Dealer 1328 Carter Street, Suite 400, Mount Airy Located Between Harbor Freight & Big Lots 336-648-8220 | [email protected] | [email protected] Tues - Fri 9:30-6:00 | Sat 9:30-3:00 Shop online at www.pilotmtnguns.com John, Malinda and Clint Riggs Look for us on Facebook & Instagram 70052283 SCENIC SCENIC CHEVROLET • BUICK FORD • LINCOLN GMC • CADILLAC www.scenicford.com PREVIEW 2021 PREVIEW www.scenicgmautos.com 1992 rockford st. -

Laura New SAG-AFTRA HEIGHT: 5’6” | WEIGHT: 115 Lbs

Laura New SAG-AFTRA HEIGHT: 5’6” | WEIGHT: 115 lbs. HAIR: Blonde | EYES: Brown ____________________________________________________________________________________________________ FILM Wild For the Night Principal Benny Boom KINTA (Four Dragons) “Rose” supporting C.L HOR/Blackbox pic. TELEVISION Latin AMA's 2018 - Pitbull Performance Dancer Liz Imperio The Voice Principal Jeri Slaughter America’s Got Talent S10 Semi Finalist Principal Freelusion ABC Pilot ‘You Got This‘ Cheerleader J.Rupert Thompson Yahoo Tv ‘Sin City Saints‘ Cheerleader Bryan Gordon Disney ‘Shake it up’ Principal Rosero Mcoy Kathy Griffin Show Principal Bravo Network Jamie & Anna’s “Big Weekend” episode Principal Nickelodeon Good Morning America Principal Fox 5 News Strictly Dancing (Australia) Featured ABC Channel Keeping up with the Kardashians Herself E! Network STAGE ‘Blanc de Blanc’ Encore Dancer Kevin Maher/Strut n Fret ‘Blanc de Blanc’ Adelaide & Newcastle Dance Captain/Performer Kevin Maher/Strut n Fret Funhouse Adelaide & Newcastle Choreographer/Performer Strut n Fret “Love Riot” Skeleton Crew Dancer Kevin Maher ‘Blanc de Blanc’ Syd Opera House/West End Principal Kevin Maher/Strut n Fret ‘AirBnb’ Industrial - LA Theatre Principal Kevin Maher Freelusion Dubai Industrial Principal Timea Papp Melbourne Cup Industrial Principal Strut n Fret Aus. Dancing with the Stars ‘Pitbull’ Principal ABC Network ‘Oakley’ Fashion Show/Industrial Principal Michael Schwandt LMFAO Las Vegas Shows Principal Sky Blu Pop Con Opening Act ‘Justin Bieber’ Principal Kevin Maher The LaLas Burlesque Show Principal Erin Lamont Kiss Fm Wango Tango Breakout Star Principal Brian Friedman M-A-C Cosmetics Live performance Model/Dancer Las Vegas Tommy Hilfiger ‘Fashions Night’ NYC Principal Dancer Kevin Maher/Teresa Esp. Curtis Adams ‘Magic that Rocks’ Tour Principal Dancer Kristin Denhey Nickelodeon Kids Choice Awards Principal Dancer Sydney Ent. -

Le Grand Sentier D'alberta

The Great Trail in Alberta Le Grand Sentier d’Alberta This marks the connection of Alberta’s section of The Great Trail of Canada in honour of Canada’s 150th anniversary Ceci marque le raccordement du Grand Sentier à travers d’Alberta pour le 150e anniversaire de la Confédération of Confederation in 2017. canadienne en 2017. À partir d’où vous êtes, vous pouvez entreprendre l’un des voyages les plus beaux et les plus diversifiés du monde. From where you are standing, you can embark upon one of the most magnificent and diverse journeys in the world. Que vous vous dirigiez vers l’est, l’ouest, le nord ou le sud, Le Grand Sentier du Canada — créé par le sentier Whether heading east, west, north or south, The Great Trail—created by Trans Canada Trail (TCT) and its partners— Transcanadien (STC) et ses partenaires — vous offre ses multiples beautés naturelles ainsi que la riche histoire et offers all the natural beauty, rich history and enduring spirit of our land and its peoples. l’esprit qui perdure de notre pays et des gens qui l’habitent. Launched in 1992, just after Canada’s 125th anniversary of Confederation The Great Trail was conceived by a group of Lancé en 1992, juste après le 125e anniversaire de la Confédération du Canada, Le Grand Sentier a été conçu, par un visionary and patriotic individuals as a means to connect Canadians from coast to coast to coast. groupe de visionnaires et de patriotes, comme le moyen de relier les Canadiens d’un océan aux deux autres. -

Roselea Blinds

The Moorabool News FREE Your Local News Tuesday 29 October, 2013 Serving Ballan and district since 1872 Phone 5368 1966 Fax 5368 2764 Vol 7 No 42 Young Ace with some fresh locally picked, sweet juicy strawberries. Photo Natasha Hurst. Festival ‘berry’ soon By Kate Taylor who will join existing event favourites. “The Strawberries & Cherries Trail this year’s free event shuttle buses, along The event will showcase not only encourages visitors to sample and taste with The Village Bacchus Marsh who are Bacchus Marsh businesses are ‘berry’ strawberries and cherries on local menus, many unique local experiences throughout sponsoring the fireworks at Bacchus Hill busy preparing for one of the town’s biggest but fruit picking, wine, heritage and arts. Bacchus Marsh. Our visitors will take Winery on the Saturday evening.” events. home the memories of our beautiful event Bacchus Marsh Tourism Association The 16 page event program is available With more than 10,000 people expected weekend, as well as multiple reasons to at participating outlets from Friday 9 to attend this year’s Strawberries & President David Durham said the 2013 event return on a regular basis over the following November. Cherries Trail Weekend, on Saturday 16 & will also appeal to quilting enthusiasts with weeks and months. Sunday 17 November, the Bacchus Marsh the Bacchus Marsh Friendship Quilters “We are very grateful to our volunteers More information on the festival can be Tourism Association announced a record hosting an exhibition at The Laurels, along and event sponsors who make all of this found at www.visitbacchusmarsh.com.au 28 Strawberry & Cherry Trail stop locations with the Blacksmith Cottage who will hold possible.