ABSTRACT Pulpit Rhetoric and the Conscience: the Gunpowder Plot

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Everard Bishop of Norwich L. Landon

186 EVERARD, BISHOP OF NORWICH. EVERARD BISHOP OF NORWICH. By L. LANDON. Owing to the identity of the name and to the fact that he had been one of the royal chaplains bishop Everard for a long time was affirmed to be Everard the son of Roger de Montgomery, Everard fitz count as he was usually called, till in 1872 a writer in Notes and, Queries adduced arguments which showed this identification to be untenable.' It is not necessary to repeat the arguments here. Since then no attempt has been made to find out who he was. Although there is nothing in the shape of definite proof there are some slight indications which suggest that he may have been Everard de CaIna, who also probably was one of Henry I's chaplains. Bartholomew Cotton' appears to be the only one of the chroniclers to record that bishop Everard at some time in his life had been archdeacon of Salis- bury. It is not easy to find information about arch- deacons at this early,date but it happens that William of Malmesbury3relates a story of a miraculous cure by S. Aldhem performed upon Everard, one of bishop Osmund's archdeacons. To be an archdeacon Everard would be at least 2.5years old and bishop Osmund died in 1099. From these two factors we get the year 1074 for the latest date of his birth, it was probably a year or two earlier. Calne being in the diocese of Salisbury there is nothing improbable in a member of a family taking its name from that place, if destined for the church, being appointed to an archdeaconry of that diocese. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The priesthood of Christ in Anglican doctrine and devotion: 1827 - 1900 Hancock, Christopher David How to cite: Hancock, Christopher David (1984) The priesthood of Christ in Anglican doctrine and devotion: 1827 - 1900, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/7473/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 VOLUME II 'THE PRIESTHOOD OF CHRIST IN ANGLICAN DOCTRINE AND DEVOTION: 1827 -1900' BY CHRISTOPHER DAVID HANCOCK The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, University of Durham, Department of Theology, 1984 17. JUL. 1985 CONTENTS VOLUME. II NOTES PREFACE 1 INTRODUCTION 4 CHAPTER I 26 CHAPTER II 46 CHAPTER III 63 CHAPTER IV 76 CHAPTER V 91 CHAPTER VI 104 CHAPTER VII 122 CHAPTER VIII 137 ABBREVIATIONS 154 BIBLIOGRAPHY 155 1 NOTES PREFACE 1 Cf. -

Mapping Mission As Translation with Reference to Michael Polanyi's

Middlesex University Research Repository An open access repository of Middlesex University research http://eprints.mdx.ac.uk Haney, Richard L. (2014) Mapping mission as translation with reference to Michael Polanyi’s heuristic philosophy. PhD thesis, Middlesex University. [Thesis] Final accepted version (with author’s formatting) This version is available at: https://eprints.mdx.ac.uk/13666/ Copyright: Middlesex University Research Repository makes the University’s research available electronically. Copyright and moral rights to this work are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners unless otherwise stated. The work is supplied on the understanding that any use for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. A copy may be downloaded for personal, non-commercial, research or study without prior permission and without charge. Works, including theses and research projects, may not be reproduced in any format or medium, or extensive quotations taken from them, or their content changed in any way, without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). They may not be sold or exploited commercially in any format or medium without the prior written permission of the copyright holder(s). Full bibliographic details must be given when referring to, or quoting from full items including the author’s name, the title of the work, publication details where relevant (place, publisher, date), pag- ination, and for theses or dissertations the awarding institution, the degree type awarded, and the date of the award. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Middlesex University via the following email address: [email protected] The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. -

The Puritan Use of Imagination

A Quarterly Journal for Church Leadership Volume 10 • Number 1 • Winter 2001 THE PURITAN USE OF IMAGINATION 7Piety is the root of charity. JOHN CALVIN Wouldest thou see a Truth within a Fable? I I heir ministers, whom Wesley consulted about their con Then read my fancies, they will stick like Burs victions, were trained at Halle, which was the centre of the ... come hither, Lutheran movement that most affected Evangelical origins: And lay my Book thy head, and Heart together. Pietism. Philip Spener had written in 1675 the manifesto of the movement, Pia Desideria, urging the need for repen Co wrote John Bunyan in his "Apology" to The Pilgrim's tance, the new birth, putting faith into practice and close o Progress at its first appearance in 1678.1 Time has proven fellowship among true believers. His disciple August him right. Few books, even of the powerful Puritan era, Francke created at Halle a range of institutions for embody make as lasting an impression on head and heart as his. ing and propagating Spener's vision. Chief among them God's truth is conveyed effectively by Bunyan's fiction.2 was the orphan house, then the biggest building in Europe, with a medical dispensary attached. It was to inspire both TRUTH ALONGSIDE FICTION Wesley and Whitefield to erect their own orphan houses Bunyan was certainly aware of the seeming inconsisten and Howel Harris to establish a community as centre of cy between "truth" and "fable." He had even sought the Christian influence at Trevecca. advice of his contemporaries about such an enterprise: DAVID W. -

The Gunpowder Plot Activity Pack

TTHHEE GGUUNNPPOOWWDDEERR PPLLOOTT The Gunpowder Plot Activity Pack Welcome to Heritage Doncaster’s the Gunpowder Plot activity pack. This booklet is filled with ideas that you can have a go at as a family at home whilst learning about the Gunpowder Plot. Some of these activities will require adult supervision as they require using an oven, a sharp implement, or could just be a bit tricky these have been marked with this warning triangle. We would love to see what you create so why not share your photos with us on social media or email You can find us at @doncastermuseum @DoncasterMuseum [email protected] Have Fun! Heritage Doncaster Education Service Contents What was the Gunpower Plot? Page 3 The Plotters Page 4 Plotters Top Trumps Page 5-6 Remember, remember Page 7 Acrostic poem Page 8 Tunnels Page 9 Build a tunnel Page 10 Mysterious letter Page 11 Letter writing Page 12 Escape and capture Page 13 Wanted! Page 14 Create a boardgame Page 15 Guy Fawkes Night Page 16 Firework art Page 17-18 Rocket experiment Page 19 Penny for a Guy Page 20 Sew your own Guy Page 21 Traditional Bonfire Night food Page 22 Chocolate covered apples Page 23 Wordsearch Page 24 What was the Gunpowder Plot? The Gunpowder Plot was a plan made by thirteen men to blow up the Houses of Parliament when King James I was inside. The Houses of Parliament is an important building in London where the government meet. It is made up of the House of Lords and the House of Commons. -

Acknowledgements There Are a Number Ofpeople Whose Assistance

Acknowledgements There are a number ofpeople whose assistance and encouragement I must acknowledge with the sincerest gratitude and thanks: Professor C. Abbott Conway, McGill University provided me with guidance and encouragement over the past year and was exceedingly generous with his time, advice, and support regarding scholarship and career direction; he also taught me the true importance of primary sources. Professor Dorothy A. Bray, McGill University, for a gentle and finn guiding hand during my time at McGill, and for telling me when to stop reading and start writing. Ruth Wehlau, PhD. (T('ronto) whose work provided the basis for so much of my own. My parents and my parents-in law: Victor and Jacqueline Solomon and Robert and Esther Luchinger whose material support allowed me to invest the time to devote myself to my studies. Liisa Stephenson whose friendship helped to keep me on an even keel through the difficult stages ofthe creative process. Jason Polley whose editorial advice was of timely assistance. This work and all else of value that I ever do I dedicate to my blessed and beloved wife Martina. John-Christian Solomon M.A. Thesis - Abstract Department of English McGill University August 2002 Thesis Title: Healdeo Trywa Wel: The English Christ Abstract: An exan1ination of extant historical and literary evidence for the purpose of questioning the standard paradigm of the "Germanization of Christianity". While the melding and inclusion of both Mediterranean and Teutonic elements in Anglo-Saxon poetry has been the subject of extensive research, until relatively recently, scholars have attributed this dynamic largely to a central manipulation of the Christian message by the Roman church with a view towards making it compatible with the societal mores of the (relatively) newly convt..rted Northern Europeans. -

Winchester Cathedral Record 2020 Number 89

Winchester Cathedral Record 2020 Number 89 Friends of Winchester Cathedral 2 The Close, Winchester, Hampshire SO23 9LS 01962 857 245 [email protected] www.winchester-cathedral.org.uk Registered Charity No. 220218 Friends of Winchester Cathedral 2020 Royal Patron Her Majesty the Queen Patron The Right Reverend Tim Dakin, Bishop of Winchester President The Very Reverend Catherine Ogle, Dean of Winchester Ex Officio Vice-Presidents Nigel Atkinson Esq, HM Lord Lieutenant of Hampshire Cllr Patrick Cunningham, The Right Worshipful, the Mayor of Winchester Ms Jean Ritchie QC, Cathedral Council Chairman Honorary Vice-President Mo Hearn BOARD OF TRUSTEES Bruce Parker, Chairman Tom Watson, Vice-Chairman David Fellowes, Treasurer Jenny Hilton, Natalie Shaw Nigel Spicer, Cindy Wood Ex Officio Chapter Trustees The Very Reverend Catherine Ogle, Dean of Winchester The Reverend Canon Andy Trenier, Precentor and Sacrist STAFF Lucy Hutchin, Director Lesley Mead Leisl Porter Friends’ Prayer Most glorious Lord of life, Who gave to your disciples the precious name of friends: accept our thanks for this Cathedral Church, built and adorned to your glory and alive with prayer and grant that its company of Friends may so serve and honour you in this life that they come to enjoy the fullness of your promises within the eternal fellowship of your grace; and this we ask for your name’s sake. Amen. Welcome What we have all missed most during this dreadfully long pandemic is human contact with others. Our own organisation is what it says in the official title it was given in 1931, an Association of Friends. -

Literaturverzeichnis in Auswahl1

Literaturverzeichnis in Auswahl1 A ADAMS, THOMAS: An Exposition upon the Second Epistle General of St. Peter. Herausgegeben von James Sherman. 1839. Nachdruck Ligonier, Pennsylvania: Soli Deo Gloria, 1990. DERS.: The Works of Thomas Adams. Edinburgh: James Nichol, 1862. DERS.: The Works of Thomas Adams. 1862. Nachdruck Eureka, California: Tanski, 1998. AFFLECK, BERT JR.: „The Theology of Richard Sibbes, 1577–1635“. Doctor of Philosophy-Dissertation: Drew University, 1969. AHENAKAA, ANJOV: „Justification and the Christian Life in John Bunyan: A Vindication of Bunyan from the Charge of Antinomianism“. Doctor of Philosophy-Dissertation: Westminster Theological Seminary, 1997. AINSWORTH, HENRY: A Censure upon a Dialogue of the Anabaptists, Intituled, A Description of What God Hath Predestinated Concerning Man. & c. in 7 Poynts. Of Predestination. pag. 1. Of Election. pag. 18. Of Reprobation. pag. 26. Of Falling Away. pag. 27. Of Freewill. pag. 41. Of Originall Sinne. pag. 43. Of Baptizing Infants. pag. 69. London: W. Jones, 1643. DERS.: Two Treatises by Henry Ainsworth. The First, Of the Communion of Saints. The Second, Entitled, An Arrow against Idolatry, Etc. Edinburgh: D. Paterson, 1789. ALEXANDER, James W.: Thoughts on Family Worship. 1847. Nachdruck Morgan, Pennsylvania: Soli Deo Gloria, 1998. ALLEINE, JOSEPH: An Alarm to the Unconverted. Evansville, Indiana: Sovereign Grace Publishers, 1959. DERS.: A Sure Guide to Heaven. Edinburgh: Banner of Truth Trust, 1995. ALLEINE, RICHARD: Heaven Opened … The Riches of God’s Covenant of Grace. New York: American Tract Society, ohne Jahr. ALLEN, WILLIAM: Some Baptismal Abuses Briefly Discovered. London: J. M., 1653. ALSTED, JOHANN HEINRICH: Diatribe de Mille Annis Apocalypticis ... Frankfurt: Sumptibus C. Eifridi, 1627. -

Introduction to the Puritans: Memorial Edition

Introduction to the Puritans Memorial Edition Erroll Hulse (1931-2017) INTRODUCTION TO THE PURITANS Erroll Hulse (1931-2017) Memorial Edition A Tribute to the Life and Ministry of Erroll Hulse Dedicated to the memory of Erroll Hulse with great joy and gratitude for his life and ministry. Many around the world will continue to benefit for many years to come from his untiring service. Those who knew him, and those who read this volume, will be blessed by his Christ- honoring life, a life well-lived to the glory of God. The following Scripture verses, psalm, and hymns were among his favorites. ISAIAH 11:9 They shall not hurt nor destroy in all my holy mountain: for the earth shall be full of the knowledge of the LORD, as the waters cover the sea. HABAKKUK 2:14 For the earth shall be filled with the knowledge of the glory of the LORD, as the waters cover the sea. PSALM 72 1Give the king thy judgments, O God, and thy righteousness unto the king’s son. 2He shall judge thy people with righteousness, and thy poor with judgment. 3The mountains shall bring peace to the people, and the little hills, by righteousness. 4He shall judge the poor of the people, he shall save the children of the needy, and shall break in pieces the oppressor. 5They shall fear thee as long as the sun and moon endure, throughout all generations. 6He shall come down like rain upon the mown grass: as showers that water the earth. 7In his days shall the righteous flourish; and abundance of peace so long as the moon endureth. -

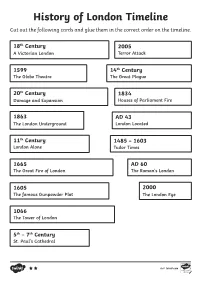

History of London Timeline Cut out the Following Cards and Glue Them in the Correct Order on the Timeline

History of London Timeline Cut out the following cards and glue them in the correct order on the timeline. 18th Century 2005 A Victorian London Terror Attack 1599 14th Century The Globe Theatre The Great Plague 20th Century 1834 Damage and Expansion Houses of Parliament Fire 1863 AD 43 The London Underground London Located 11th Century 1485 – 1603 London Alone Tudor Times 1665 AD 60 The Great Fire of London The Roman’s London 1605 2000 The famous Gunpowder Plot The London Eye 1066 The Tower of London 5th – 7th Century St. Paul’s Cathedral visit twinkl.com This famous theatre is where many Unfortunately, there was lots of damage to of William Shakespeare’s plays were London due to bombings during the Second performed. However, in 1613, it was World War including to St. Paul’s Cathedral. burnt down by a staged cannon fire in London once again expanded and many one of his plays. Today, a new 1990s big department stores such as Harrods and Globe Theatre, close to the original Selfridges were built. building, still holds performances of Shakespeare’s plays. 200 years after Guy Fawkes tried to Due to its trading links, Britain and London blow up the Houses of Parliament, became very powerful with goods from all over an accidental fire spread through the world being imported. the main building leaving only Westminster Hall undamaged. The th During the 18 century and Queen Victoria’s replacement was built ten years reign, the population of London expanded and later and still remains there today. many of the buildings we still see in London today were built during the Victorian times. -

Apostolic Discourse and Christian Identity in Anglo-Saxon Literature

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Illinois Digital Environment for Access to Learning and Scholarship Repository APOSTOLIC DISCOURSE AND CHRISTIAN IDENTITY IN ANGLO-SAXON LITERATURE BY SHANNON NYCOLE GODLOVE DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2010 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Charles D. Wright, Chair Associate Professor Renée Trilling Associate Professor Robert W. Barrett Professor Emerita Marianne Kalinke ii ABSTRACT “Apostolic Discourse and Christian Identity in Anglo-Saxon Literature” argues that Anglo-Saxon religious writers used traditions about the apostles to inspire and interpret their peoples’ own missionary ambitions abroad, to represent England itself as a center of religious authority, and to articulate a particular conception of inspired authorship. This study traces the formation and adaptation of apostolic discourse (a shared but evolving language based on biblical and literary models) through a series of Latin and vernacular works including the letters of Boniface, the early vitae of the Anglo- Saxon missionary saints, the Old English poetry of Cynewulf, and the anonymous poem Andreas. This study demonstrates how Anglo-Saxon authors appropriated the experiences and the authority of the apostles to fashion Christian identities for members of the emerging English church in the seventh and eighth centuries, and for vernacular religious poets and their readers in the later Anglo-Saxon period. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am indebted to many people for their help and support throughout the duration of this dissertation project. -

Puritanism Notes

Puritanism Who were the Puritans? They are a group of Protestants in England who sought to purify (hence the name, “puritan”) the Church of England (Anglicanism) by removing the elements of Anglican Christianity that they considered to be too “Roman Catholic.” They are the type of Christianity that dominated the colonies in North America. What did the Puritans oppose in the Church of England? Answer: Anything they considered to be too “Roman Catholic” -Using crosses in churches -Certain priestly garments -Celebrating communion at an altar -Religious images -Wealth and luxury -Bishops (though some Puritans allowed for an episcopacy) -Celebrating Christmas or saint’s days -Having godparents -Kneeling during communion -Having an organ in church -Etc. Where did the Puritans come from? They primarily arose during the reign of Elizabeth in England (a Protestant) who hoped the Church of England would be a middle way (via media) between Roman Catholicism and Protestantism. Whereas Anglicanism (and episcopacy) united the country, the Puritans wanted presbyterian or congregational leadership which threatened the unity of England. In 1593 an act was passed that allowed Puritans to be arrested if they didn’t attend Anglican church services. After Elizabeth died she was succeeded by James I. James needed the bishops of the Church of England to unify his country, so religious groups that did not belong to that (Anabaptists, Independents, etc.) received less toleration. In 1605, due to English oppression of Catholics, a group of Catholics rented a space below where the British Parliament met. There they put large wine barrels filled with gunpowder in an attempt to blow up the king and several Puritans who sat in Parliament.