Ian Burrell Media Journalist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COMMUNICATIONS in CUMBRIA : an Overview

Cumbria County History Trust (Database component of the Victoria Country History Project) About the County COMMUNICATIONS IN CUMBRIA : An overview Eric Apperley October 2019 The theme of this article is to record the developing means by which the residents of Cumbria could make contact with others outside their immediate community with increasing facility, speed and comfort. PART 1: Up to the 20th century, with some overlap where inventions in the late 19thC did not really take off until the 20thC 1. ANCIENT TRACKWAYS It is quite possible that many of the roads or tracks of today had their origins many thousands of years ago, but the physical evidence to prove that is virtually non-existent. The term ‘trackway’ refers to a linear route which has been marked on the ground surface over time by the passage of traffic. A ‘road’, on the other hand, is a route which has been deliberately engineered. Only when routes were engineered – as was the norm in Roman times, but only when difficult terrain demanded it in other periods of history – is there evidence on the ground. It was only much later that routes were mapped and recorded in detail, for example as part of a submission to establish a Turnpike Trust.11, 12 From the earliest times when humans settled and became farmers, it is likely that there was contact between adjacent settlements, for trade or barter, finding spouses and for occasional ritual event (e.g stone axes - it seems likely that the axes made in Langdale would be transported along known ridge routes towards their destination, keeping to the high ground as much as possible [at that time (3000-1500BC) much of the land up to 2000ft was forested]. -

Andy Higgins, BA

Andy Higgins, B.A. (Hons), M.A. (Hons) Music, Politics and Liquid Modernity How Rock-Stars became politicians and why Politicians became Rock-Stars Thesis submitted for the degree of Ph.D. in Politics and International Relations The Department of Politics, Philosophy and Religion University of Lancaster September 2010 Declaration I certify that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in substantially the same form for the award of a higher degree elsewhere 1 ProQuest Number: 11003507 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11003507 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract As popular music eclipsed Hollywood as the most powerful mode of seduction of Western youth, rock-stars erupted through the counter-culture as potent political figures. Following its sensational arrival, the politics of popular musical culture has however moved from the shared experience of protest movements and picket lines and to an individualised and celebrified consumerist experience. As a consequence what emerged, as a controversial and subversive phenomenon, has been de-fanged and transformed into a mechanism of establishment support. -

Н. А. Зелинская Modern British and Russian Press

Министерство образования и науки Российской Федерации Н. А. ЗЕЛИНСКАЯ ФГБОУ ВПО «Удмуртский государственный университет» Факультет профессионального иностранного языка MODERN Кафедра профессионального иностранного языка № 2 BRITISH AND RUSSIAN PRESS Н. А. Зелинская MODERN BRITISH AND RUSSINA PRESS Учебно-методическое пособие Ижевск 2012 Ижевск 2012 УДК 811.111’25 (07) Содержание ББК 81.432.1-9 З – 494 Введение 3 Рекомендовано к изданию Учебно-методическим Советом УдГУ UNIT 1. THE MODERN BRITISH PRESS 4 Рецензент – кандидат педагогических наук, доцент Е. А. Калач UNIT 2. RUSSIAN PRESS 37 Зелинская Н. А. UNIT 3. BRITISH TELEVISION AND RADIO 55 З - 494 Modern British and Russian press: учеб.-метод. пособие / УдГУ, Ижевск, 2012. - 86 с. Основной целью данного пособия является обучение UNIT 4. RUSSIAN TELEVISION AND RADIO 71 студентов навыкам чтения и перевода англоязычных текстов, отражающих историю и современное состояние прессы в Великобритании и России. Упражнения пособия направлены как на формирование навыков самостоятельной работы студентов, так и на выполнение заданий в аудитории под руководством СПИСОК ЛИТЕРАТУРЫ ПО КУРСУ 85 преподавателя. Данное пособие может представлять интерес для студентов, преподавателей вузов и учителей школ, а также всех интересующихся историей, культурой и СМИ двух стран – Великобритании и России. © Н.А. Зелинская, 2012 Введение Unit 1. THE MODERN BRITISH PRESS Учебно-методическое пособие «Modern British and Text 1.The British newspapers Russian Press» по английскому языку предназначено для бакалавров 1 и 2 года обучения по направлению подготовки The British press consists of several kinds of newspapers. The 100400 «Туризм», 031600 «Реклама и связи с общественностью», national papers are the ones sold all over the country, with a 03500 «Издательское дело и редактирование», 033000 large circulation, giving general news. -

Feral Beast": Cautionary Lessons from British Press Reform Lili Levi University of Miami School of Law, [email protected]

University of Miami Law School University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository Articles Faculty and Deans 2015 Taming the "Feral Beast": Cautionary Lessons From British Press Reform Lili Levi University of Miami School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/fac_articles Part of the Communications Law Commons, and the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons Recommended Citation Lili Levi, Taming the "Feral Beast": Cautionary Lessons From British Press Reform, 55 Santa Clara L. Rev. 323 (2015). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty and Deans at University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TAMING THE "FERAL BEAST"1 : CAUTIONARY LESSONS FROM BRITISH PRESS REFORM Lili Levi* TABLE OF CONTENTS Introdu ction ............................................................................ 324 I. British Press Reform, in Context ....................................... 328 A. Overview of the British Press Sector .................... 328 B. The British Approach to Newspaper Regulation.. 330 C. Phone-Hacking and the Leveson Inquiry Into the Culture, Practices and Ethics of the Press ..... 331 D. Where Things Stand Now ...................................... 337 1. The Royal Charter ............................................. 339 2. IPSO and IM -

PSA Awards 2005

POLITICAL STUDIES ASSOCIATION AWARDS 2005 29 NOVEMBER 2005 Institute of Directors, 116 Pall Mall, London SW1Y 5ED Political Studies Association Awards 2005 Sponsors The Political Studies Association wishes to thank the sponsors of the 2005 Awards: Awards Judges Event Organisers Published in 2005 by Edited by Professor John Benyon Political Studies Association: Political Studies Association Professor Jonathan Tonge Professor Neil Collins Jack Arthurs Department of Politics Dr Catherine McGlynn Dr Catherine Fieschi Professor John Benyon University of Newcastle Professor John Benyon Professor Charlie Jeffery Dr Justin Fisher Newcastle upon Tyne Jack Arthurs Professor Wyn Grant Professor Ivor Gaber NE1 7RU Professor Joni Lovenduski Professor Jonathan Tonge Designed by Professor Lord Parekh Tel: 0191 222 8021 www.infinitedesign.com Professor William Paterson Neil Stewart Associates: Fax: 0191 222 3499 Peter Riddell Eileen Ashbrook e-mail: [email protected] Printed by Neil Stewart Yvonne Le Roux Potts Printers Liz Parkin www.psa.ac.uk Miriam Sigler Marjorie Thompson Copyright © Political Studies Association. All rights reserved Registered Charity no. 1071825 Company limited by guarantee in England and Wales no. 3628986 A W ARDS • 2004 Welcome I am delighted to welcome you to the Political Studies Association 2005 Awards. This event offers a rare opportunity to celebrate the work of academics, politicians and journalists. The health of our democracy requires that persons of high calibre enter public life. Today we celebrate the contributions made by several elected parliamentarians of distinction. Equally, governments rely upon objective and analytical research offered by academics. Today’s event recognizes the substantial contributions made by several intellectuals who have devoted their careers to the conduct of independent and impartial study. -

Untitled-1 1 Contents Highlights New Acquisitions Lifestyle, Health & Wellbeing Non Fiction Fiction Recently Published

Untitled-1 1 Contents Highlights New Acquisitions Lifestyle, Health & Wellbeing Non Fiction Fiction Recently Published Picador Contacts Sophie Brewer, Associate Publisher: [email protected] Jon Mitchell, Rights Director: [email protected] Anna Shora, Senior Rights Manager: [email protected] Mairéad Loftus, Rights Executive: [email protected] Aisling Brennan, Rights Assistant: [email protected] Sub-Agents Brazil – Tassy Barham Baltic states – ANA Baltic Bulgaria and Serbia – ANA Sofia *China – ANA Beijing *China – Peony Literary Agency Czech & Slovak Reps – ANA Prague Greece – J.L.M. Agency Hungary & Croatia – ANA Budapest Israel – The Deborah Harris Agency *Japan – The English Agency *Japan – Tuttle-Mori *Japan – Japan Uni Korea – Eric Yang Agency Romania – Simona Kessler Russia – ANA Moscow *Taiwan – ANA Taipei *Taiwan – Peony Literary Agency Turkey – Anatolia Lit * Non-exclusive agent Highlights Lily's Promise How I Survived Auschwitz and Found the Strength to Live Lily Ebert and Dov Forman The incredibly moving and powerful memoir of an Auschwitz survivor who made headlines around the world in 2020. A heart-wrenching and ultimately life-affirming story that demonstrates the power of love to see us through the darkest of times. When Holocaust survivor Lily Ebert was liberated in 1945, a Jewish-American soldier gave her a banknote on which he’d written ‘Good luck and happiness’. And when her great-grandson, Dov, decided to use social media to track down the family of the GI in 2020, 96-year-old Lily found herself making headlines around the world. Lily had promised herself that if she survived Auschwitz she would tell everyone the truth about the camp. -

Birmingham Exceptionalism, Joseph Chamberlain and the 1906 General Election

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Archive, E-theses Repository Birmingham Exceptionalism, Joseph Chamberlain and the 1906 General Election by Andrew Edward Reekes A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of Master of Research School of History and Cultures University of Birmingham March 2014 1 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract The 1906 General Election marked the end of a prolonged period of Unionist government. The Liberal Party inflicted the heaviest defeat on its opponents in a century. Explanations for, and the implications of, these national results have been exhaustively debated. One area stood apart, Birmingham and its hinterland, for here the Unionists preserved their monopoly of power. This thesis seeks to explain that extraordinary immunity from a country-wide Unionist malaise. It assesses the elements which for long had set Birmingham apart, and goes on to examine the contribution of its most famous son, Joseph Chamberlain; it seeks to establish the nature of the symbiotic relationship between them, and to understand how a unique local electoral bastion came to be built in this part of the West Midlands, a fortress of a durability and impregnability without parallel in modern British political history. -

Drama Co- Productions at the BBC and the Trade Relationship with America from the 1970S to the 1990S

ORBIT - Online Repository of Birkbeck Institutional Theses Enabling Open Access to Birkbecks Research Degree output ’Running a brothel from inside a monastery’: drama co- productions at the BBC and the trade relationship with America from the 1970s to the 1990s http://bbktheses.da.ulcc.ac.uk/56/ Version: Full Version Citation: Das Neves, Sheron Helena Martins (2013) ’Running a brothel from inside a monastery’: drama co-productions at the BBC and the trade relationship with America from the 1970s to the 1990s. MPhil thesis, Birkbeck, University of Lon- don. c 2013 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copyright law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit guide Contact: email BIRKBECK, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON SCHOOL OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY OF ART AND SCREEN MEDIA MPHIL VISUAL ARTS AND MEDIA ‘RUNNING A BROTHEL FROM INSIDE A MONASTERY’: DRAMA CO-PRODUCTIONS AT THE BBC AND THE TRADE RELATIONSHIP WITH AMERICA FROM THE 1970s TO THE 1990s SHERON HELENA MARTINS DAS NEVES I hereby declare that this is my own original work. August 2013 ABSTRACT From the late 1970s on, as competition intensified, British broadcasters searched for new ways to cover the escalating budgets for top-end drama. A common industry practice, overseas co-productions seems the fitting answer for most broadcasters; for the BBC, however, creating programmes that appeal to both national and international markets could mean being in conflict with its public service ethos. Paradoxes will always be at the heart of an institution that, while pressured to be profitable, also carries a deep-rooted disapproval of commercialism. -

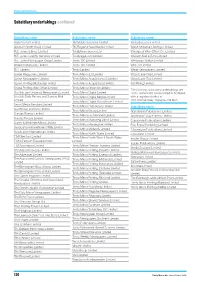

Subsidiary Undertakings Continued

Financial Statements Subsidiary undertakings continued Subsidiary name Subsidiary name Subsidiary name Planetrecruit Limited TM Mobile Solutions Limited Websalvo.com Limited Quids-In (North West) Limited TM Regional New Media Limited Welsh Universal Holdings Limited R.E. Jones & Bros. Limited Totallyfinancial.com Ltd Welshpool Web-Offset Co. Limited R.E. Jones Graphic Services Limited Totallylegal.com Limited Western Mail & Echo Limited R.E. Jones Newspaper Group Limited Trinity 100 Limited Whitbread Walker Limited Reliant Distributors Limited Trinity 102 Limited Wire TV Limited RH1 Limited Trinity Limited Wirral Newspapers Limited Scene Magazines Limited Trinity Mirror (L I) Limited Wood Lane One Limited Scene Newspapers Limited Trinity Mirror Acquisitions (2) Limited Wood Lane Two Limited Scene Printing (Midlands) Limited Trinity Mirror Acquisitions Limited Workthing Limited Scene Printing Web Offset Limited Trinity Mirror Cheshire Limited The following subsidiary undertakings are Scottish and Universal Newspapers Limited Trinity Mirror Digital Limited 100% owned and incorporated in Scotland, Scottish Daily Record and Sunday Mail Trinity Mirror Digital Media Limited with a registered office at Limited One Central Quay, Glasgow, G3 8DA. Trinity Mirror Digital Recruitment Limited Smart Media Services Limited Trinity Mirror Distributors Limited Subsidiary name Southnews Trustees Limited Trinity Mirror Group Limited Aberdonian Publications Limited Sunday Brands Limited Trinity Mirror Huddersfield Limited Anderston Quay Printers Limited Sunday -

Air Pollution, Politics, and Environmental Reform in Birmingham, Alabama J. Merritt Mckinney Doctor of Philosophy

RICE UNIVERSITY Air Pollution, Politics, and Environmental Reform in Birmingham, Alabama 1940-1971 by J. Merritt McKinney A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE Doctor of Philosophy APPROVED, THESIS COMMITTEE: . Boles, Chair am P. Hobby Professor of History Martin V. Melosi Professor of History University of Houston ~~ Assistant Professor of History Daniel Cohan Assistant Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering HOUSTON, TEXAS OCTOBER 2011 Copyright J. Merritt McKinney 2011 ABSTRACT Air Pollution, Politics, and Environmental Reform in Birmingham, Alabama, 1940-1971 by J. Merritt McKinney This dissertation contends that efforts to reduce air pollution in Birmingham, Alabama, from the 1940s through the early 1970s relied on citizens who initially resisted federal involvement but eventually realized that they needed Washington's help. These activists had much in common with clean air groups in other U.S. cities, but they were somewhat less successful because of formidable industrial opposition. In the 1940s the political power of the Alabama coal industry kept Birmingham from following the example of cities that switched to cleaner-burning fuels. The coal industry's influence on Alabama politics had waned somewhat by the late 1960s, but U.S. Steel and its allies wielded enough political power in 1969 to win passage of a weak air pollution law over one favored by activists. Throughout this period the federal government gradually increased its involvement in Alabama's air pollution politics, culminating in the late 1960s and early 1970s with the enactment of environmental laws that empowered federal officials to pressure Alabama to pass a revised 1971 air pollution law that met national standards. -

Download Winter 2011

2011Winter_Cover_finalrev_Winter05Cover 7/6/10 5:05 PM Page 1 Grove Press Grove Press Celebrates Its 60th Anniversary Celebrating 60 Years of Groundbreaking Publishing 1951–2011 n 1951 Barney Rosset took over a small reprint publisher, Grove Atlantic Monthly Press IPress. Over the next three-and-a-half decades, he and his colleagues Richard Seaver, Gilbert Sorrentino, Fred Jordan, Kent Carroll, Nat Sobel, Herman Graf, and many others created what was one of the Black Cat and Granta most important publishing enterprises of the late-twentieth century. Grove published many of the Beats, including William S. Burroughs, Jack Kerouac, and Allen Ginsberg. Grove became the preeminent pub- lisher of drama in America, publishing the work of Samuel Beckett (Nobel Prize for Literature 1969), Bertold Brecht, Eugene Ionesco, Harold Pinter (Nobel Prize for Literature 2005), Tom Stoppard, and many more. The press introduced American readers to the work of international authors including Jorge Luis Borges, Mikhail Bulgakov, Jean Genet, Pablo Neruda, Kenzaboro Oe (Nobel Prize for Literature 1994), Octavio Paz (Nobel Prize for Literature 1990), Elfriede Jelinek (Nobel Prize for Literature 2004), and Juan Rulfo. In the late 1950s thly Pr and early 1960s, Barney Rossett challenged the U.S. obscenity laws by on es A publishing D. H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover and then Henry A M s Miller’s Tropic of Cancer. His landmark court victories changed the t t c l l i American cultural landscape. Grove Press went on to publish literary t erotic classics like The Story of O and groundbreaking fiction like John n Rechy’s City of Night, as well as the works of the Marquis de Sade. -

Blair: Bombing Iraq Better. Again

Blair: Bombing Iraq Better. Again By David Cromwell and David Edwards Region: Middle East & North Africa Global Research, June 16, 2014 Theme: Media Disinformation, US NATO Media Lens War Agenda In-depth Report: IRAQ REPORT Over the weekend, the British media was awash with the blood-splattered Tony Blair’s self- serving attempts to justify the illegal invasion of Iraq in 2003. The coverage was sparked by a new essay in which Blair claimed that the chaos in Iraq was the ‘predictable and malign effect’ of the West having ‘watched Syria descend into the abyss’ without bombing Assad. Blair advocated yet more Western violence, more bombing: ‘On the immediate challenge President Obama is right to put all options on the table in respect of Iraq, including military strikes on the extremists…’ Par for the course, the liberal wing of the corporate media, notably the Guardian and BBC News, led with Blair’s sophistry. (See image, courtesy of News Unspun). Blair told Andrew Marr on BBC1 that: ‘washing our hands of the current problem would not make it go away’. The choice of phrase is telling. The image of Blair attempting to wash away the blood of one million Iraqis is indelible. The Guardian’s editors performed painful contortions to present an illusion of reasoned analysis, declaring that Blair’s essay was both ‘thoughtful’ and ‘wrong-headed’. Robert Fisk’s response to Blair was rather different: ‘How do they get away with these lies?’ In the Guardian editorial, titled ‘a case of blame and shame’, the key phrase was: ‘If there has to be a hierarchy of blame for Iraq, however, it must surely begin with Saddam.’ Of course, ‘surely’! But only if the Guardian’s editors feel compelled to keep selling one core ideological message to its audience.