This Electronic Thesis Or Dissertation Has Been Downloaded from the King's Research Portal At

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Barton Stacey Conservation Area Character Appraisal 1 Introduction

Barton Stacey Conservation Area Character Appraisal 1 Introduction Conservation Areas A conservation area is an area designated by the local planning authority as one of special architectural or historic interest. Once designated, the local authority has a duty1 to ensure that the character of a conservation area is preserved or enhanced, particularly when considering applications for development. Purpose of Character Appraisals Local authorities are encouraged to prepare Character Appraisals, providing detailed assessments of their conservation areas. Appraisals enable the local authority to understand the elements that give each area its distinct and unique character, identifying special qualities and highlighting features of particular signifi cance. Those elements include: historic development; landscape and topography; style, type and form of the buildings, and the spaces between buildings; materials, textures, colours and detailing; and less tangible aspects, such as sounds and smells, which can contribute to the special character of the area. A Character Appraisal is intended as an overview, providing a framework within which individual planning applications can be assessed. It includes text, an appraisal plan and photographs. It is not realistic to refer to every building or feature within a conservation area – but the omission of any part does not mean that it is without signifi cance. 1 Under the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990. 2 2 The Barton Stacey Conservation Area Context Barton Stacey Conservation Area was originally designated on 25th April 1984 in recognition of its special architectural and historic interest. Local authorities have a duty to periodically review their conservation areas to ensure that they are still relevant and that boundaries are logical and could be defended if a planning appeal were made. -

Southwick Priory Fishponds: Excavations 1987

Proc. Hampsh. Field Club Archaeol. Soc. 46, 1990, 53-72 SOUTHWICK PRIORY FISHPONDS: EXCAVATIONS 1987 by C K CURRIE decided that the recently discovered earth ABSTRACT works, henceforth known as the lower pond, should be allowed to stay as they were after a The topographical and historical context of the previously much neglected fishponds of Southwick Priory, is examined. limited research excavation had been under Archaeological excavation of a series of trenches, designed to taken. elucidate the evolution of the ponds from their origins in the This research was designed to answer a wide late 12th or early 13th century, is described. There is general range of questions about fishponds that were agreement between the archaeological and historical evidence. urgently in need of answer as outlined by Aston (1988, 4) and Chambers with Gray (1988, 113-35). It particularly attempted to INTRODUCTION concentrate on recovering information on the constructional methods employed in building The site of the Augustinian priory of South the ponds and obtaining reliable dating evi wick stands within the grounds of a land Naval dence. Base, HMS Dryad. Before the Second World War, this land had been occupied by South wick Park, the estate of Southwick House, FOUNDATION home of the Borthwick-Norton family. During the war the site was purchased by the Ministry Southwick Priory began its existence c. 1128 of Defence whose agents, the Property Services within the outer bailey of Portchester Castle. Agency, managed the land at the time of the Controversy over this foundation has been excavations. recently elucidated by Mason (1980, 1-10) Prior to the summer of 1985, the greater part who has identified William de Pont de l'Arche, of the earthworks here under discussion had a former sheriff of Hampshire, as the true not been identified as they lay under thick founder (Mason 1980, 1). -

Week Ending: 16Th November 2012 ______

TEST VALLEY BOROUGH COUNCIL – PLANNING SERVICES _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ WEEKLY LIST OF PLANNING APPLICATIONS AND NOTIFICATIONS : NO. 46 Week Ending: 16th November 2012 _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Comments on any of these matters should be forwarded IN WRITING (including fax and email) to arrive before the expiry date shown in the second to last column Head of Planning and Building Beech Hurst Weyhill Road ANDOVER SP10 3AJ In accordance with the provisions of the Local Government (Access to Information Act) 1985, any representations received may be open to public inspection. You may view applications and submit comments on-line – go to www.testvalley.gov.uk APPLICATION NO./ PROPOSAL LOCATION APPLICANT CASE OFFICER/ PREVIOUS REGISTRATION PUBLICITY APPLICA- TIONS DATE EXPIRY DATE 12/02464/FULLN Erection of first floor Grasmere , Church Road, Mr Neil Palmer Miss Emma Jones 13.11.2012 extension to provide Abbotts Ann, Andover 14.12.2012 ABBOTTS ANN additional living space. Hampshire SP11 7BH Erection of integral car barn 12/02520/TREEN T1 Prunus crown reduce by Bywaters, Duck Street, Abbotts Mr Mundy Mrs Jan Olverson 14.11.2012 up to 2m height and spread Ann, Andover Hampshire SP11 11.12.2012 ABBOTTS ANN 7AZ 12/02440/FULLN Erection of bungalow and 51 Blendon Drive, Andover, Mr And Mrs K George Miss Emma Jones YES 15.11.2012 construction of vehicular Hampshire, SP10 3NG 10.12.2012 ANDOVER TOWN access (HARROWAY) 12/02435/FULLN Addition of brick walls, 8 Lillywhite Crescent, Andover, Mr And Mrs Miss Sarah Barter 16.11.2012 gateposts and driveway Hampshire, SP10 5NA Christopher Peck 11.12.2012 ANDOVER TOWN gates to the front of the (ALAMEIN) property Week Ending: 16th November 2012 APPLICATION NO./ PROPOSAL LOCATION APPLICANT CASE OFFICER/ PREVIOUS REGISTRATION PUBLICITY APPLICA- TIONS DATE EXPIRY DATE 12/02481/TPON 2036 - Beech. -

Estate Management in the Winchester Diocese Before and After the Interregnum: a Missed Opportunity

Proc. Hampshire Field Club Archaeol. Soc. 61, 2006, 182-199 (Hampshire Studies 2006) ESTATE MANAGEMENT IN THE WINCHESTER DIOCESE BEFORE AND AFTER THE INTERREGNUM: A MISSED OPPORTUNITY By ANDREW THOMSON ABSTRACT specific in the case of the cathedral and that, over allocation of moneys, the bishop seems The focus of this article is the management of the to have been largely his own man. Business at episcopal and cathedral estates of the diocese of Win the cathedral was conducted by a 'board', that chester in the seventeenth century. The cathedral is, the dean and chapter. Responsibilities in estates have hardly been examined hitherto and the diocese or at the cathedral, however, were previous discussions of the bishop's estates draw ques often similar if not identical. Whether it was a tionable conclusions. This article will show that the new bishop's palace or a new chapter house, cathedral, but not the bishop, switched from leasing both bishop and cathedral clergy had to think, for 'lives' to 'terms'. Olhenvise, either through neglect sometimes, at least, not just of themselves and or cowardice in the face of the landed classes, neither their immediate gains from the spoils, but also really exploited 'early surrenders' or switched from, of the long term. Money was set aside accord leasing to the more profitable direct farming. Rental ingly. This came from the resources at the income remained static, therefore, with serious impli bishop's disposal - mainly income from his cations for the ministry of the Church. estates - and the cathedral's income before the distribution of dividends to individual canons. -

Manor Farm East Dean, Salisbury SP5 1HB a Quintessential Farmhouse with Extensive Outbuildings, Fishing and Paddocks

Manor Farm East Dean, Salisbury Manor Farm including the Test. There is fine pheasant and partridge shooting and golf available locally. East Dean, Salisbury SP5 1HB The area provides ample scope for walking and riding both locally and also in the New Forest. In A quintessential Farmhouse addition there is sailing and other water sports with extensive outbuildings, on the South coast and Solent. fishing and paddocks Road and rail links from Manor Farm are excellent with a regular service to London Romsey 8 miles, Salisbury 10 miles, Waterloo from nearby Grateley Station (from 80 Stockbridge 11.5 miles, Winchester 18 miles, minutes). Access to the M3 and A303 provide Southampton 16 miles. fast links to London, the M25, Heathrow and the West Country. Southampton airport is Hall | Sitting room | Dining room | Kitchen/ approximately 18 miles. breakfast room | Study | Utility room | Shower The property room | Master bedroom with dressing room and Manor Farm is a unique and magical Grade II ensuite bathroom | 5 Further bedrooms | Family listed farmhouse set in beautiful surroundings bathroom | 2 Bedroom cottage | Studio flat with plenty of space both inside and out. The Timber framed barn | Studio | Office | Stables original cottage was built in the early 18th Established gardens | Garden room | Double century and believed to be originally two bank fishing | Paddocks cottages, with numerous outbuildings added About 11.3 acres in the 19th century. The current owners have lovingly restored the farmhouse and integrated Location it with the granary, creating a spacious family Manor Farm is situated on the edge of the small home with scope to continue this further. -

Diocesan Prayer Cycle 1St October - 31St December

Diocesan Prayer Cycle 1st October - 31st December What is a Diocese and how do we work together within it? At its simplest, a Diocese is a geographical area; a region; a collection of parishes, benefices, deaneries, archdeaconries. But it is more than that – it is a gathering of all our communities in mutual support for each other. And as the Diocese of Winchester, we each play our part in the growth of God’s Kingdom committed to our vision of ‘living the mission of Jesus’. This prayer diary helps us to get to know each other better, to find out what is happening across the area and to see how God is working and using us all in his mission across the region. The early church shared good news of what was happening across a wide area, as churches grew, and more people came to know Christ. In their commitment to love and care for one another, prayer lay at the heart of their lives. As we use this Prayer Diary, let’s seek to share that love and care for each other and to rejoice in what God is doing amongst us. This month... how might you pray for young people? For example, you might focus on school leavers, students, youth workers, community centres, young people in trouble... How might you be part of the answer to your prayers? For example, you might make a point of smiling at young people in the street; volunteer for a helpline; get involved with your local Further Education College; support parents you know whose young adult children are struggling.. -

Week Ending 12Th February 2010

TEST VALLEY BOROUGH COUNCIL – PLANNING SERVICES _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ WEEKLY LIST OF PLANNING APPLICATIONS AND NOTIFICATIONS : NO. 06 Week Ending: 12th February 2010 _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Comments on any of these matters should be forwarded IN WRITING (including fax and email) to arrive before the expiry date shown in the second to last column For the Northern Area to: For the Southern Area to: Head of Planning Head of Planning Beech Hurst Council Offices Weyhill Road Duttons Road ANDOVER SP10 3AJ ROMSEY SO51 8XG In accordance with the provisions of the Local Government (Access to Information Act) 1985, any representations received may be open to public inspection. You may view applications and submit comments on-line – go to www.testvalley.gov.uk APPLICATION NO./ PROPOSAL LOCATION APPLICANT CASE OFFICER/ PREVIOUS REGISTRATION PUBLICITY APPLICA- TIONS DATE EXPIRY DATE 10/00166/FULLN Erection of two replacement 33 And 34 Andover Road, Red Mr & Mrs S Brown Jnr Mrs Lucy Miranda YES 08.02.2010 dwellings together with Post Bridge, Andover, And Mr R Brown Page ABBOTTS ANN garaging and replacement Hampshire SP11 8BU 12.03.2010 and resiting of entrance gates 10/00248/VARN Variation of condition 21 of 11 Elder Crescent, Andover, Mr David Harman Miss Sarah Barter 10.02.2010 TVN.06928 - To allow garage Hampshire, SP10 3XY 05.03.2010 ABBOTTS ANN to be used for storage room -

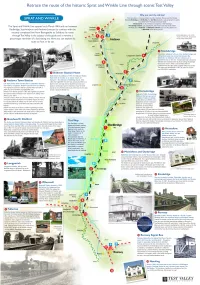

Sprat and Winkle Line Leaflet

k u . v o g . y e l l a v t s e t @ e v a e l g d t c a t n o c e s a e l P . l i c n u o C h g u o r o B y e l l a V t s e T t a t n e m p o l e v e D c i m o n o c E n i g n i k r o w n o s n i b o R e l l e h c i M y b r e h t e g o t t u p s a w l a i r e t a m e h T . n o i t a m r o f n I g n i d i v o r p r o f l l e s d n i L . D r M d n a w a h s l a W . I r M , n o t s A H . J r M , s h p a r g o t o h p g n i d i v o r p r o f y e l r e s s a C . R r M , l l e m m a G . C r M , e w o c n e l B . R r M , e n r o H . M r M , e l y o H . R r M : t e l f a e l e l k n i W d n a t a r p S e h t s d r a w o t n o i t a m r o f n i d n a s o t o h p g n i t u b i r t n o c r o f g n i w o l l o f e h t k n a h t o t e k i l d l u o w y e l l a V t s e T s t n e m e g d e l w o n k c A . -

A Vington. 4 Miles. Awbridge. 15 Miles. Baddesley (North). Wmiles

1913] A VINGTON AND AWBRIDGE DIRECTORY. 325 Emmence, C., Buildings farm Hillier, W., farmer Johnson, H., Ashley farm Hurst, F. (post office), builder and Kimber, H. (assistant- overseer), contractor Stock bridge Hurst, J. W., Danes farm Lawrence, W. E., Forest farm J udd, Francis, dealer, Coles farm Pile, G. (head gamekeeper) Lever, S., Banksia Verrier, J ., bee keeper and farmer Mills, E., schoolmistress • Moody, G., dealer, the Hollies A vington. 4 miles. Moody, Miss 1., the Bungalow (Post Town-Alresford.) Nutbeam, H., Red cottage, Danes-rd. Population, 232, Olden, George, farmer Shelley,Capt.Sir John C. E., Bart.,J.P. Olden, W., farmer Osmond, Rev. P. H., M.A., Rectory Preston, - police constable • Adderley, Capt. E., Home farm Roles, Mrs., Corona cottage Shelley, H ubert, Lovington farm Sillence, G., farmer Shelley, Percy Bysshe , Spare, Mrs., shopkeeper Beasley, H., painter Styles, 1. Danes road Bowers, W., dairyman and manager, Warwick, G. E., farmer A vington Park dairy Wools, F., cycle engineer Hall, Richard, parish clerk Wools, W. S., blacksmith & shopkpr. Harnett, W., gardener Harper, Mrs., Post office Baddesley (North). wmiles. Norris, H., carpenter, Sawmills Padwick, C. H., farm manager, See North Baddesley. Avington farm Samways, Miss, schoolmistress Barton Stacey. 8 miles. Sims, Mrs., dressmaker Postal Address-S.O., Hants. Overseers-Sir J. Shelley & J. Tanner Population, 528. Cockrane, G. Awbridge. 15 miles. Franklin, Rev. A. C., vicar (Post Town-Romsey.) Frazer, C. H. De Horsey, Admiral, Bochurst, Gardiner, H. J., Moody's down Awbridge Heath, Mrs. Hansard, H. L., Stanbridge hall Hodgson, R. K., Gravelacre Hargrave, Rev. A. B., M.A., Incum- Judd, E. -

Hyde Abbey: a Typical Benedictine Monastery of the 12Th Century

Hyde Abbey: A Typical Benedictine Monastery of the 12th Century The translation of the bones of King Alfred to Hyde Abbey in 1110 Plan of Hyde Abbey overlaid on to today’s street plan Hyde Abbey was and early stopping off In purely architectural accommodation for exceptional in its age point on the pilgrims’ terms, however, Hyde visitors and other offices. because it had the honour way from Winchester to Abbey would have been Consequently the abbey and responsibility of Canterbury. The royal very typical of Benedictine church built by Henry looking after the remains graves were set before the abbeys of the Norman I in Reading in the of King Alfred the Great High Altar while the side era. By the 12th century 1120s – inspired one can and his family. It also chapels might well have what might be regarded reasonably imagine by acquired a number of hosted the relics. Pilgrims as a standard pattern had Hyde Abbey – was very relics, notably those of St. would have processed emerged in the design much along the same lines Josse (also known as St. around the side aisles to of these abbey churches as Hyde in its layout. Judoc). This made it in absorb the holiness which along with their associated later years, an important emanated from them. cloisters, dormitories, Wherwell Abbey Romsey Abbey Hyde Abbey Winchester Cathedral Comparative length of Hyde Abbey and other contemporary abbeys and churches Capital example on display at St. Bartholomew, Hyde Building Materials Decoration Because of the Cathedral, stone was Artistically, the plain Today the Priory Church predominance of chalk necessary. -

XIX.—Reginald, Bishop of Bath (Hjjfugi); His Episcopate, and His Share in the Building of the Church of Wells. by the Rev. C. M

XIX.—Reginald, bishop of Bath (HJJfUgi); his episcopate, and his share in the building of the church of Wells. By the Rev. C. M. CHURCH, M.A., F.8.A., Sub-dean and Canon Residentiary of Wells. Read June 10, 1886. I VENTURE to think that bishop Eeginald Fitzjocelin deserves a place of higher honour in the history of the diocese, and of the fabric of the church of Wells, than has hitherto been accorded to him. His memory has been obscured by the traditionary fame of bishop Robert as the "author," and of bishop Jocelin as the "finisher," of the church of Wells; and the importance of his episcopate as a connecting link in the work of these two master-builders has been comparatively overlooked. The only authorities followed for the history of his episcopate have been the work of the Canon of Wells, printed by Wharton, in his Anglia Sacra, 1691, and bishop Godwin, in his Catalogue of the Bishops of England, 1601—1616. But Wharton, in his notes to the text of his author, comments on the scanty notice of bishop Reginald ;a and Archer, our local chronicler, complains of the unworthy treatment bishop Reginald had received from Godwin, also a canon of his own cathedral church.b a Reginaldi gesta historicus noster brevius quam pro viri dignitate enarravit. Wharton, Anglia Sacra, i. 871. b Historicus noster et post eum Godwinus nimis breviter gesta Reginaldi perstringunt quae pro egregii viri dignitate narrationem magis applicatam de Canonicis istis Wellensibus merita sunt. Archer, Ghronicon Wellense, sive annales Ecclesiae Cathedralis Wellensis, p. -

Romsey Abbey

A S H O RT ACCO UN T OF ROMSEY AB B EY . A D ESCRI PTI ON OF T H E FAB RI C ‘ AN D NOT E S ON T H E H I STO RY OF T H E V MARY CON ENT OF S S . ET H E LF LED A -“V [A r BY THE RE V. T . PE RKINS R OF N R SE R E CTO TU R WO TH , DOR T “ ” ” “ A EN S E N B N E AUTHOR OF M I , ROU , WIM OR ” A N D S E T C. CHRI TCHURCH , W I TH $ $$I I ILLUS TRATIONS LONDON GEORGE BE L L AND S ONS 1 9 07 O CH ’S WI CK PRESS : CHARLES WHITTI N GHAM AN D CO v Q . ‘ s l O KS R N N N D N . O COU T , CHA CERY LA E , LO O P R E F ACE I T H E architecturaland descriptive part of this book is the result of a of careful personal examination the f bric, made when the author has visited the abbey at various times during the last twenty years . The illustrations are reproduced from photo of graphs taken by him on the occasions these visits . The historical information has been derived from many “ sources . Among these may especially be mentioned An Essay ” C . descriptive of the Abbey Church of Romsey, by Spence, the first edition of which was published in 1 85 1 ; the small ofiicial guide sold in the church , and Records of Romsey m Abbey, compiled from anuscript and printed records, by .