Belarus 2014 Human Rights Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The EU and Belarus – a Relationship with Reservations Dr

BELARUS AND THE EU: FROM ISOLATION TOWARDS COOPERATION EDITED BY DR. HANS-GEORG WIECK AND STEPHAN MALERIUS VILNIUS 2011 UDK 327(476+4) Be-131 BELARUS AND THE EU: FROM ISOLATION TOWARDS COOPERATION Authors: Dr. Hans-Georg Wieck, Dr. Vitali Silitski, Dr. Kai-Olaf Lang, Dr. Martin Koopmann, Andrei Yahorau, Dr. Svetlana Matskevich, Valeri Fadeev, Dr. Andrei Kazakevich, Dr. Mikhail Pastukhou, Leonid Kalitenya, Alexander Chubrik Editors: Dr. Hans-Georg Wieck, Stephan Malerius This is a joint publication of the Centre for European Studies and the Konrad- Adenauer-Stiftung. This publication has received funding from the European Parliament. Sole responsibility for facts or opinions expressed in this publication rests with the authors. The Centre for European Studies, the Konrad-Adenauer- Stiftung and the European Parliament assume no responsibility either for the information contained in the publication or its subsequent use. ISBN 978-609-95320-1-1 © 2011, Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V., Sankt Augustin / Berlin © Front cover photo: Jan Brykczynski CONTENTS 5 | Consultancy PROJECT: BELARUS AND THE EU Dr. Hans-Georg Wieck 13 | BELARUS IN AN INTERnational CONTEXT Dr. Vitali Silitski 22 | THE EU and BELARUS – A Relationship WITH RESERvations Dr. Kai-Olaf Lang, Dr. Martin Koopmann 34 | CIVIL SOCIETY: AN analysis OF THE situation AND diRECTIONS FOR REFORM Andrei Yahorau 53 | Education IN BELARUS: REFORM AND COOPERation WITH THE EU Dr. Svetlana Matskevich 70 | State bodies, CONSTITUTIONAL REALITY AND FORMS OF RULE Valeri Fadeev 79 | JudiciaRY AND law -

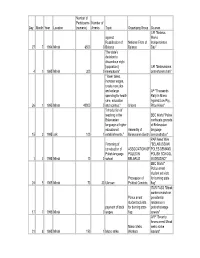

Protests in Belarus (1994-2011) .Pdf

Number of Participants Number of Day Month Year Location (numeric) Arrests Topic Organizing Group Sources UPI "Belarus against Marks Russification of National Front of Independence 27 7 1994 Minsk 6500 0 Belarus Belarus Day" "the state's decision to discontinue eight [opposition] UPI "Belarussians 4 1 1995 Minsk 300 0 newspapers" protest press ban" " lower taxes, increase wages, create new jobs and enlarge AP "Thousands spending for health Rally In Minsk care, education Against Low Pay, 26 1 1995 Minsk 40000 0 and science." Unions Price Hikes" "introduction of teaching in the BBC World "Police Belarussian confiscate grenade language at higher at Belarussian educational Assembly of language 15 2 1995 unk 100 1 establishments," Belarussian Gentry demonstration" PAP News Wire Financing of "BELARUSSIAN construction of ASSOCIATION OF POLES DEMAND Polish language POLES IN POLISH SCHOOL 1 3 1995 Minsk 10 0 school BELARUS IN GRODNO" BBC World " Police arrest student activists Procession of for burning state 24 5 1995 Minsk 70 30 Uknown Political Convicts flag" ITAR-TASS "Minsk workers march on Police arrest presidential student activists residence in payment of back for burning state protest at wage 17 7 1995 Minsk . 0 wages flag arrears" AFP "Security forces arrest Minsk Minsk Metro metro strike 21 8 1995 Minsk 150 1 Metro strike Workers leaders" Number of Participants Number of Day Month Year Location (numeric) Arrests Topic Organizing Group Sources Interfax "Belarusian Popular Front Reconsideration of protests against oil oil agreement with -

Truth Stumbles in the Street Christian Democratic Activism in Belarus

Truth Stumbles in the Street Christian Democratic Activism in Belarus Geraldine Fagan Abstract: Few are aware that prominent figures in the Belarusian opposition movement are motivated by Christian conviction. In this article, the author trac- es how President Alexander Lukashenko’s restriction of religious freedom has prompted Catholics, Orthodox, and Protestants to turn toward democratic activ- ism; it also discusses their rediscovery of religious freedom as a long-standing core value of Belarusian identity. The author’s findings draw on interviews con- ducted in Minsk in the aftermath of the December 2010 presidential election, including those with Christian opposition activists who were subsequently jailed. Keywords: Belarus, democracy, freedom, religion nce a dictatorial regime has muzzled civil society’s more cantankerous O elements—rival political parties and the independent media—a stage is reached at which faith groups, even if falteringly, join the vanguard in the struggle for freedom and justice. In 1980s Communist Poland, the Catholic Church offered a vital moral platform for mass dissent by the Solidarity movement. Prayer meetings at a Leipzig Lutheran church formed the nucleus of protest by hundreds of thousands of East Germans in the weeks before the Berlin Wall fell in 1989. Might faith-inspired opposition similarly prove a catalyst for political change in Belarus, dubbed “the last true dictatorship in the center of Europe” by United States Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice in 2005?1 The prospects Geraldine Fagan is a 2010–2011 Joseph R. Crapa Fellow at the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom. She has monitored religious freedom in Belarus since 2003 as the Moscow correspondent for Forum 18 News Service. -

BELARUS Restrictions on the Political and Civil Rights of Citizens Following the 2010 Presidential Election

BELARUS Restrictions on the Political and Civil Rights of Citizens Following the 2010 Presidential Election of person. Article 4: No one shall be held in slavery Article 1: All human beings are born free and equal or servitude; slavery and the slave trade shall be prohibited in all their forms. Article 5: No one shall be subjected to in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. Article 6: Everyone has the right to recognition spirit of brotherhood. Article 2: Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, everywhere as a person before the law. Article 7: All are equal before the law and are entitled without any discrimi- without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, nation to equal protection of the law. All are entitled to equal protection against any discrimination in violation of this national or social origin, property, birth or other status. Furthermore, no distinction shall be made on the Declaration and against any incitement to such discrimination. Article 8: Everyone has the right to an effective rem- basis of the political, jurisdictional or international status of the country or territory to which a person edy by the competent national tribunals for acts violating the fundamental rights granted him by the constitution or belongs, whether it be independent, trust, non-self-governing or under any other limitation of sovereignty. by law. Article 9: No one shall be subjected to arbitrary arrest, Article 3: Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security June 2011 564a Uladz Hrydzin © This report has been produced with the support of the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA). -

Monitoring Report on Developments in Belarus October 2008 - February 2009

MONITORING REPORT ON DEVELOPMENTS IN BELARUS OCTOBER 2008 - FEBRUARY 2009 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY As the six-month EU-Belarus dialogue period draws to a close, this monitoring report has been prepared by Belarusian civil society organisations and their international partners 1 to ensure that detailed information regarding the actual situation on the ground in Belarus is available to decision makers reviewing the EU decision on suspending sanctions for Belarus. The report draws the following conclusions: • The steps taken by the Belarusian authorities during this dialogue period have been primarily cosmetic and are ultimately reversible; the process has been neither systematic nor institutionalized. While a small number of organizations have benefited, little has been done to facilitate the functioning of independent civic and media sectors in any meaningful manner. • The minor changes have not addressed the core problems facing civil society in Belarus today. On-going restrictions on human rights and fundamental freedoms continue to cause concern and demonstrate that Belarus has not yet begun a meaningful democratization process. In particular, the authorities’ repression against young political and civic activists, as well as religious minorities, continues unabated. But rather than creating more political prisoners, more subtle forms of repression, including forced military service and “restricted freedom” (house arrest) are increasingly being utilized to control civic and political activists. • While the recent steps by the Belarusian government -

Belarus 50 Days After: Facts, Moods, Forecast

ЦЭНТАР ПАЛІТЫЧНАЙ АДУКАЦЫІ CENTER FOR POLITICAL EDUCATION Miensk, Republic of Belarus Е-mail: [email protected] Gutta cavat lapidem Belarus 50 days after: Facts, moods, forecast I. Introduction: This analysis has been prepared by the Andrei Liakhovich of the Minsk-based Center for Political Education for the purpose of the Slovak-Belarus Task Force analyzing the current political developments of the authorities, the political opposition and society of Belarus 50 days after the referendum. The overall objective of the Slovak-Belarus Task Force is to establish a framework for Slovak know-how transfer to Belarus on key aspects of civil society development. The project seeks to assist civil society in Belarus in preparation for the upcoming presidential elections scheduled for 2006 and further integrate think tanks within civil society in Belarus by linking their expertise and capacity with Belarusian NGOs through the Task Force. II. Summary: One can characterized the post-referendum political situation in Belarus as Lukashenka`s positions was strengthened (since the referendum was unchallenged both by domestic forces and international community compare to Ukraine) and by crisis of the opposition. However, first time there are preconditions for overcoming inter-coalition and inter-party contradictions paralyzing the opposition for a long period. Nevertheless, even in this case the opposition needs stronger international attention for preventing Lukashenka getting elected in 2006. The nature of political development of Belarus will to a greater extend (also first time) depend not on he administration, but on how fast the opposition will able to form an effective coalition, as well as on the efficiency of the Belarus policy of the European Union and the United States. -

Belarus by Alexei Pikulik, Dzianis Melyantsou Et Al

Belarus by Alexei Pikulik, Dzianis Melyantsou et al. Capital: Minsk Population: 9.5 million GNI/capita, PPP: US$14,460 Source: The data above are drawn from the World Bank’sWorld Development Indicators 2013. Nations in Transit Ratings and Averaged Scores 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 Electoral Process 6.75 7.00 7.00 7.00 7.00 6.75 6.75 7.00 7.00 7.00 Civil Society 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.50 6.50 6.25 6.00 6.00 6.25 6.50 Independent Media 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.50 6.75 6.75 6.75 Governance* 6.50 n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a National Democratic Governance n/a 6.75 7.00 7.00 7.00 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 Local Democratic Governance n/a 6.50 6.50 6.50 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 Judicial Framework and Independence 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 7.00 7.00 Corruption 5.75 6.00 6.25 6.25 6.25 6.00 6.00 6.00 6.25 6.25 Democracy Score 6.54 6.64 6.71 6.68 6.71 6.57 6.50 6.57 6.68 6.71 * Starting with the 2005 edition, Freedom House introduced separate analysis and ratings for national democratic governance and local democratic governance to provide readers with more detailed and nuanced analysis of these two important subjects. -

Analysis of the Work of the West in Belarus Plan

Analysis of the work of the West in Belarus Plan Introduction 3 Brain centers 4 Electronic media 5 NСOs 6 Bloggers and social media 7 Discrediting of the ROC 8 Discreditation of the BRYU 10 Construction of the Atomic Power Station 12 Kurapaty 14 Anniversary of the BPR 17 Map of campaigns 20 Conclusions 21 Social Engineering Agency 2 Introduction The programmed change of social and cultural codes of society is the main task of soft power technologies. To develop an effective model of protection against these technologies, it is necessary to understand the tasks, tools, mechanics and details of the work of the interventionists in the recipient countries “absolutely”. For this, the Matrix of influence (hereinafter MI) was developed. This is a scheme for analyzing the tools, activities and methods of the interventionists. With the help of MI the work of the interventionists in the Republic of Belarus was analyzed. Belarus has been chosen as the actual field of confrontation between Russia and the West. The MI of interventionists in Belarus were shown instantly - an analysis of the tools on a specific date, as well as within the framework of a mechanic of 5 selected campaigns. Task. The main objective of the study is to analyze the activities of the matrix of influence of Western stakeholders in Belarus on the example of five campaigns: “discredit of the Russian Orthodox Church”, “discredit of the Belarusian Republican Youth Union”, “construction of the Atomic Power Station”, “Kurapaty” and “anniversary of the BPR”. These campaigns are analyzed both qualitatively and quantitatively. Qualitative indicators include an analysis of the level of tools involved, the structure of the media used, etc. -

Democratic Transition in Belarus: Cause(S) of Failure

STUDENT PAPER SERIES03 Democratic Transition in Belarus: Cause(s) of Failure Yauheniya Nechyparenka Master’s in International Relations Academic year 2010-2011 I hereby certify that this dissertation contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. I hereby grant to IBEI the non-exclusive license to archive and make accessible my dissertation in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I retain all ownership rights to the copyright of the dissertation. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this dissertation. Yauheniya Nechyparenka Word count: 9 995 Mount Kisco, NY 30/09/20 Table of Contents I. Introduction 1. Introduction 2 2. Methodology and structure 3 II. Literature review and theoretical framework 4 1 ‘Political’ hypothesis 7 2. ‘Social’ hypothesis 8 3. ‘External Forces’ hypotheses: 3.1. International democracy assistance 9 3.2. The relationship with autocratic hegemon 11 III. Case-study Analysis: Belarus 12 1. Unpopular incumbent leader - united opposition 14 2. Youth movement 16 3. Western-funded international organizations 19 4. Relationship with Russia 22 IV. Conclusion 27 V. References 28 i ABSTRACT The purpose of the research is to identify the causes of the constant fail of the ‘electoral’ democratic transition in the Republic of Belarus in the last decade. -

Belarus — Towards a United Europe

1 BELARUS — TOWARDS A UNITED EUROPE Jan Nowak-Jeziorański College of Eastern Europe Wrocław 2009 2 Прага вясны BELARUS – TOWARDS A UNITED EUROPE Jan Nowak-Jeziorański College of Eastern Europe Wrocław 2009 Edited by Mariusz Maszkiewicz Co-operation: Marta Pejda Translated by Alyaksandr Yanusik Proof-reading: Simon M. Lewis The publication has been financed by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Poland ISBN: 978-83-61617-76-1 3 Contents Introduction Mariusz Maszkiewicz Belarus – towards a United Europe................................................................ 5 I European Programmes for Belarus Vyachaslau Pazdnyak Expanding European neighbourhood menus for Belarus: In search of a gourmet ...................................................................................21 Alena Rakava Evaluation of the previous programmes of the European Union ................ 42 II Belarusian Society and Authorities in the Process of Searching the European Way Andrey Lyakhovich Belarus’ ruling elite: Readiness for dialogue and cooperation with the EU .....................................................................................................61 Yury Chavusau Belarus’ civil society in the context of dialogue with the EU .......................82 Iryna Vidanava I’m Lovin’ It! Belarusian youth and Europe .................................................98 Ihar Lyalkou The EU in the platforms of Belarus’ political parties .................................. 117 III Belarus and NATO Andrey Fyodarau Belarus-NATO relations: Current -

Belarus by Andrei Kazakevich Capital: Minsk Population: 9.5 Million GNI/Capita, PPP: $17,220

Belarus By Andrei Kazakevich Capital: Minsk Population: 9.5 million GNI/capita, PPP: $17,220 Source: World Bank World Development Indicators. Nations in Transit Ratings and Averaged Scores NIT Edition 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 Electoral Process 6.75 6.75 7.00 7.00 7.00 7.00 7.00 6.75 6.75 6.75 Civil Society 6.25 6.00 6.00 6.25 6.50 6.50 6.50 6.25 6.25 6.25 Independent 6.75 6.50 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 Media National 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.50 6.75 Democratic Governance Local Democratic 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 Governance Judicial 6.75 6.75 6.75 7.00 7.00 7.00 7.00 7.00 7.00 7.00 Framework and Independence Corruption 6.00 6.00 6.00 6.25 6.25 6.25 6.25 6.25 6.25 6.00 Democracy Score 6.57 6.5 6.57 6.68 6.71 6.71 6.71 6.64 6.61 6.61 NOTE: The ratings reflect the consensus of Freedom House, its academic advisers, and the author(s) of this report. The opinions expressed in this report are those of the author(s). The ratings are based on a scale of 1 to 7, with 1 representing the highest level of democratic progress and 7 the lowest. -

Belarus by Vitali Silitski

Belarus by Vitali Silitski Capital: Minsk Population: 9.7 million GNI/capita: US$9,700 The social data above was taken from the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development’s Transition Report 2007: People in Transition, and the economic data from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators 2008. Nations in Transit Ratings and Averaged Scores 1999 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 Electoral Process 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 7.00 7.00 7.00 7.00 Civil Society 6.00 6.50 6.25 6.50 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.50 6.50 Independent Media 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 Governance* 6.25 6.25 6.50 6.50 6.50 n/a n/a n/a n/a National Democratic 7.00 Governance n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a 6.75 7.00 7.00 Local Democratic 6.75 Governance n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a 6.50 6.50 6.50 Judicial Framework 6.75 and Independence 6.50 6.757 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 Corruption 5.25 5.25 5.25 5.50 5.75 6.00 6.25 6.25 6.25 Democracy Score 6.25 6.38 6.38 6.46 6.54 6.64 6.71 6.68 6.71 * With the 2005 edition, Freedom House introduced separate analysis and ratings for national democratic governance and local democratic governance to provide readers with more detailed and nuanced analysis of these two important subjects.