Mind the Gap: Bringing Progressive Movements and Parties Together

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Social Dialogue and Economic Performance What Matters for Business - a Review

Social Dialogue and Economic Performance What matters for business - A review Damian Grimshaw Aristea Koukiadaki Isabel Tavora CONDITIONS OF WORK AND EMPLOYMENT SERIES No. 89 INWORK Conditions of Work and Employment Series No. 89 Social Dialogue and Economic Performance: What Matters for Business - A review Damian Grimshaw Aristea Koukiadaki Isabel Tavora Work and Equalities Institute, University of Manchester, UK INTERNATIONAL LABOUR OFFICE - GENEVA Copyright © International Labour Organization 2017 First published 2017 Publications of the International Labour Office enjoy copyright under Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. Nevertheless, short excerpts from them may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated. For rights of reproduction or translation, application should be made to ILO Publications (Rights and Licensing), International Labour Office, CH-1211 Geneva 22, Switzerland, or by email: [email protected]. The International Labour Office welcomes such applications. Libraries, institutions and other users registered with a reproduction rights organization may make copies in accordance with the licences issued to them for this purpose. Visit www.ifrro.org to find the reproduction rights organization in your country. ISSN: 2226-8944 ; 2226-8952 (web pdf). The designations employed in ILO publications, which are in conformity with United Nations practice, and the presentation of material therein do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the International Labour Office concerning the legal status of any country, area or territory or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers. The responsibility for opinions expressed in signed articles, studies and other contributions rests solely with their authors, and publication does not constitute an endorsement by the International Labour Office of the opinions expressed in them. -

The Generation Gap, Or Belarusian Differences in Goals, Values and Strategy 2 3

1 The Generation Gap, or Belarusian Differences in Goals, Values and Strategy 2 3 The Generation Gap, or Belarusian Differences in Goals, Values and Strategy Edited by Andrej Dynko 4 Komitet Redakcyjny: Andrzej Sulima-Kamiński, Valer Bulhakau, Andrej Dynko, Eulalia Łazarska, Amanda Murphy. © Copyright by Wyższa Szkoła Handlu i Prawa im. Ryszarda Łazarskiego w Warszawie, Instytut Przestrzeni Obywatelskiej i Polityki Społecznej, Warszawa 2008 Projekt jest współfinansowany przez National Endowment for Democracy. Oficyna Wydawnicza Wyższej Szkoły Handlu i Prawa im. Ryszarda Łazarskiego 02-662 Warszawa ul. Świeradowska 43 tel. 022 54-35-450 e-mail: [email protected] www.lazarski.edu.pl ISBN 978-83-60694-19-0 Materiały z konferencji w dniach 3-5 czerwca 2006 r. Nakład 300 egz. DegVXdlVc^Z`dbejiZgdlZ!Ygj`^degVlV/ 9dbLnYVlc^Xon:A>EH6! ja#>c[aVcX`V&*$&.-!%%"&-.LVghoVlV iZa#$[Vm%''+(*%(%&!%''+(*&,-*! Z"bV^a/Za^ehV5Za^ehV#ea!lll#Za^ehV#ea 5 CONTENTS Andrzej Sulima Kaminski. A few words of introduction ............................................7 THE GENERATION GAP: THE MOTOR OR THE BRAKES ? Jan Maksymiuk. Is the Belarusian Oppositio n Losing the Battle for Young Minds? ................................................................................................. 13 Dzianis Mieljancou. The Change of Generations within the Belarusian Opposition: Is There a Conflict? .................................................. 18 Walter Stankevich. A New Wave of Emigrants: Varied Goals and Values ............... 22 Ales Mikhalevich. Generations -

International Journal of Arts and Humanities (IJAH) Bahir Dar- Ethiopia Vol

IJAH VOL 4 (3) SEPTEMBER, 2015 55 International Journal of Arts and Humanities (IJAH) Bahir Dar- Ethiopia Vol. 4(3), S/No 15, September, 2015:55-63 ISSN: 2225-8590 (Print) ISSN 2227-5452 (Online) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/ijah.v4i3.5 The Metamorphosis of Bourgeoisie Politics in a Modern Nigerian Capitalist State Uji, Wilfred Terlumun, PhD Department of History Federal University Lafia Nasarawa State, Nigeria E-mail: [email protected] or [email protected] Tel: +2347031870998 or +2348094009857 & Uhembe, Ahar Clement Department of Political Science Federal University Lafia, Nasarawa State-Nigeria Abstract The Nigerian military class turned into Bourgeoisie class has credibility problems in the Nigerian state and politics. The paper interrogates their metamorphosis and masquerading character as ploy to delay the people-oriented revolution. The just- concluded PDP party primaries and secondary elections are evidence that demands a verdict. By way of qualitative analysis of relevant secondary sources, predicated on the Marxian political approach, the paper posits that the capitalist palliatives to block the Nigerian people from freeing themselves from the shackles of poverty will soon be a Copyright ©IAARR 2015: www.afrrevjo.net Indexed African Journals Online: www.ajol.info IJAH VOL 4 (3) SEPTEMBER, 2015 56 thing of the past. It is our argument that this situation left unchecked would create problem for Nigeria’s nascent democracy which is not allowed to go through normal party polity and electoral process. The argument of this paper is that the on-going recycling of the Nigerian military class into a bourgeois class as messiahs has a huge possibility for revolution. -

SAKHAROV PRIZE NETWORK NEWSLETTER 10/2015 Raif Badawi Is the Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought's Newest Laureate 29/10/2015

SAKHAROV PRIZE NETWORK NEWSLETTER 10/2015 Raif Badawi is the Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought's newest laureate 29/10/2015 the Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought for 2015 has been awarded to Saudi blogger Raif Badawi. EP President Schulz called Badawi ‘a hero in our modern internet world who is fighting for democracy and facing real torture’ as he announced the decision taken by the Conference of Presidents. ‘I have asked the King of Saudi Arabia to pardon Badawi and release him to give him the chance to receive the Sakharov Prize here in the European Parliament’, the EP President and Sakharov Prize Network co-chair said. Badawi was shortlisted as a finalist for the Prize together with the Democratic Opposition in Venezuela and murdered Russian opposition politician and activist Boris Nemtsov by a vote of the Foreign Affairs and Development Committees. The initial list of nominees included also Edna Adan Ismail, Nadiya Savchenko, and Edward Snowden, Antoine Deltour and Stéphanie Gibaud. Link: President Schulz press point Flogging of Raif Badawi to resume, wife warns 27/10/2015: Ensaf Haidair, the wife of Saudi blogger, 2015 SP laureate, Raif Badawi, said she has been informed that the Saudi authorities have given the green light to the resumption of her husband's flogging. In a statement published on the Raif Badawi Foundation website, Haidar said that she received her information from the same source who had warned her about Badawi’s pending flogging at the beginning of January 2015, a few days before Badawi was flogged. Link: Fondation Raif Badawi Xanana Gusmao and DEVE Delegation at Milan EXPO on Feeding the Planet 15/10/2015: 1999 Sakharov Prize laureate and first President of Timor-Leste, Xanana Gusmão, and a delegation of the EP’s DEVE Committee led by Chairwoman and SPN Member Linda McAvan tackled the right to food, land rights and the use of research for the effective realisation of the Sustainable Development Goals during an intensive two day-programme in Milan. -

The EU and Belarus – a Relationship with Reservations Dr

BELARUS AND THE EU: FROM ISOLATION TOWARDS COOPERATION EDITED BY DR. HANS-GEORG WIECK AND STEPHAN MALERIUS VILNIUS 2011 UDK 327(476+4) Be-131 BELARUS AND THE EU: FROM ISOLATION TOWARDS COOPERATION Authors: Dr. Hans-Georg Wieck, Dr. Vitali Silitski, Dr. Kai-Olaf Lang, Dr. Martin Koopmann, Andrei Yahorau, Dr. Svetlana Matskevich, Valeri Fadeev, Dr. Andrei Kazakevich, Dr. Mikhail Pastukhou, Leonid Kalitenya, Alexander Chubrik Editors: Dr. Hans-Georg Wieck, Stephan Malerius This is a joint publication of the Centre for European Studies and the Konrad- Adenauer-Stiftung. This publication has received funding from the European Parliament. Sole responsibility for facts or opinions expressed in this publication rests with the authors. The Centre for European Studies, the Konrad-Adenauer- Stiftung and the European Parliament assume no responsibility either for the information contained in the publication or its subsequent use. ISBN 978-609-95320-1-1 © 2011, Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V., Sankt Augustin / Berlin © Front cover photo: Jan Brykczynski CONTENTS 5 | Consultancy PROJECT: BELARUS AND THE EU Dr. Hans-Georg Wieck 13 | BELARUS IN AN INTERnational CONTEXT Dr. Vitali Silitski 22 | THE EU and BELARUS – A Relationship WITH RESERvations Dr. Kai-Olaf Lang, Dr. Martin Koopmann 34 | CIVIL SOCIETY: AN analysis OF THE situation AND diRECTIONS FOR REFORM Andrei Yahorau 53 | Education IN BELARUS: REFORM AND COOPERation WITH THE EU Dr. Svetlana Matskevich 70 | State bodies, CONSTITUTIONAL REALITY AND FORMS OF RULE Valeri Fadeev 79 | JudiciaRY AND law -

Language Management and Language Problems in Belarus: Education and Beyond

Language Management and Language Problems in Belarus: Education and Beyond Markus Giger Institute of the Czech Language, Prague, Czech Republic Maria´n Sloboda Charles University in Prague, Czech Republic This article provides an overview of the sociolinguistic situation in Belarus, the most russified of the post-Soviet countries. It summarizes language policy and legislation, and deals in more detail with language management and selected language problems in Belarusian education. It also contributes to the work on language planning by applying Jernudd’s and Neustupny´’s Language Management Theory, particularly the concept of the language management cycle, to analysis of sociolinguistic issues in Belarus. doi: 10.2167/beb542.0 Keywords: Belarus, bilingual education, language management, language problems Introduction Belarus (or Belorussia/Byelorussia) became independent in 1991 with the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Its independence was not welcomed with much enthusiasm by the population that had strong emotional and cultural ties with Russia and the Soviet Union. Starting in 1994, this attitude resulted in political changes, which returned the country to the Soviet patterns of government, economy, social life, and linguistic development. The majority of the population of Belarus prefers to use Russian, although they declare to be ethnically Belarusian. Nevertheless, Belarusian is not limited to a minority group, members of the Russian-speaking majority also use it for symbolic functions. The language is still an obligatory subject in all Belarusian schools and has the status of a state language alongside Russian. This situation is a result of sociohistorical processes which have taken place in the Belarusian territory and which we will describe briefly in the Historical Background section. -

Political Party Defections by Elected Officers in Nigeria: Nuisance Or Catalyst for Democratic Reforms?

International Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Studies Volume 7, Issue 2, 2020, PP 11-23 ISSN 2394-6288 (Print) & ISSN 2394-6296 (Online) Political Party Defections by Elected Officers in Nigeria: Nuisance or Catalyst for Democratic Reforms? Enobong Mbang Akpambang, Ph.D1*, Omolade Adeyemi Oniyinde, Ph.D2 1Senior Lecturer and Acting Head, Department of Public Law, Ekiti State University, Ado-Ekiti, Nigeria 2Senior Lecturer and Acting Head, Department of Jurisprudence and International Law, Faculty of Law, Ekiti State University, Ado-Ekiti, Nigeria *Corresponding Author: Enobong Mbang Akpambang, Ph.D, Senior Lecturer and Acting Head, Department of Public Law, Ekiti State University, Ado-Ekiti, Nigeria. ABSTRACT The article interrogated whether defections or party switching by elected officers, both in Nigeria‟s executive and legislative arms of government, constitutes a nuisance capable of undermining the country‟s nascent democracy or can be treated as a catalyst to ingrain democratic reforms in the country. This question has become a subject of increasing concerns in view of the influx of defections by elected officers from one political party to the other in recent times, especially before and after election periods, without the slightest compunction. It was discovered in the article that though the Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria 1999 (as amended) has made significant provisions regarding prohibition of defection, except in deserving cases, yet elected officers go about „party-prostituting‟ with reckless abandon. The article concludes that political party defections by elected officers, if left unchecked, may amount to a nuisance capable of undermining the democratic processes in Nigeria in the long run. -

The Politicisation of Trade Unionism: the Case of Labour/NCNC Alliance in Nigeria 1940-1960

The Politicisation of Trade Unionism: The Case of Labour/NCNC Alliance in Nigeria 1940-1960 Rotimi Ajayi Abstract: Trade unions generally played a major role in the nationalist struggle for independence in Nigeria. A major highlight of this role was the alliance between organised labour and the National Council of Nigerian Citizens (NCNC), one of the prominent political panics in the vanguard of the anti-colonial struggle. This paper traces the genesis of the labour movement in Nigeria with a view to establishing the background to the labour/ NCNC alliance. It also identilies the impact the resultant politicization of labour activities (which the alliance engendered) has had on post-colonial Nigerian political sening. Introduction This paper is an analysis of the alliance between organised Labour and the National Council of Nigerian Citizens (NCNC), one of the prominent political associations in the vanguard of the anti-colonial struggle in Nigeria. The paper examines the background to the alliance and its impact on the trade union movement in Nigeria. The study dates back to 1940 when trade unionism was injected with radical political values and consciousness, and ends in 1960, the date of independence from colonial rule. The work is divided into four major sections. The first part shows the emergence of the early generation of trade unions in Nigeria. The second and third explain the process ofradicalisation of trade union consciousness, and the politicisation of the Labour movement respectively. The fourth part discusses the state oforganised labour following its involvement in partisan politics and its implications for the post-colonial state. -

Protests in Belarus (1994-2011) .Pdf

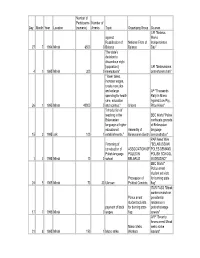

Number of Participants Number of Day Month Year Location (numeric) Arrests Topic Organizing Group Sources UPI "Belarus against Marks Russification of National Front of Independence 27 7 1994 Minsk 6500 0 Belarus Belarus Day" "the state's decision to discontinue eight [opposition] UPI "Belarussians 4 1 1995 Minsk 300 0 newspapers" protest press ban" " lower taxes, increase wages, create new jobs and enlarge AP "Thousands spending for health Rally In Minsk care, education Against Low Pay, 26 1 1995 Minsk 40000 0 and science." Unions Price Hikes" "introduction of teaching in the BBC World "Police Belarussian confiscate grenade language at higher at Belarussian educational Assembly of language 15 2 1995 unk 100 1 establishments," Belarussian Gentry demonstration" PAP News Wire Financing of "BELARUSSIAN construction of ASSOCIATION OF POLES DEMAND Polish language POLES IN POLISH SCHOOL 1 3 1995 Minsk 10 0 school BELARUS IN GRODNO" BBC World " Police arrest student activists Procession of for burning state 24 5 1995 Minsk 70 30 Uknown Political Convicts flag" ITAR-TASS "Minsk workers march on Police arrest presidential student activists residence in payment of back for burning state protest at wage 17 7 1995 Minsk . 0 wages flag arrears" AFP "Security forces arrest Minsk Minsk Metro metro strike 21 8 1995 Minsk 150 1 Metro strike Workers leaders" Number of Participants Number of Day Month Year Location (numeric) Arrests Topic Organizing Group Sources Interfax "Belarusian Popular Front Reconsideration of protests against oil oil agreement with -

Against the Death Penalty What Is It? Goals

WORLD CONGRESS AGAINST THE DEATH PENALTY 26TH FEBRUARY - 1ST MARCH 2019 - BRUSSELS - BELGIUM Organised by In partnership with Sponsored by Held under the patronage of Co-funded by the European Union congres.ecpm.org #7CongressECPM WORLD CONGRESS AGAINST THE DEATH PENALTY WHAT IS IT? GOALS Encourage the involvement in the international anti-death penalty movement: private Date: 26 February to 1 March 2019 sector, sports, etc. Location: Brussels (Belgium) Put in place a global strategy to move the last retentionist countries towards abolition. Duration: 4 days Accompany Africa towards abolition: could Africa be the next abolitionist continent? Number of participants: 1,500 per day Counter populist movements, make progress in raising awareness about abolition and make Reach of the event: an average of 115 countries represented at previous congresses younger generations actors of change. Break the isolation of civil society, which works on a daily basis to abolish the death penalty The 7th World Congress in Brussels has been preceded by the 3rd Regional Congress Against the death in retentionist or moratorium countries by promoting networking. Death Penalty which took place on 9 and 10 April 2018 in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire. Raise awareness among the Belgian population and teach young people, from Belgium and beyond, about abolition of the death penalty. Organiser: ECPM (Together against the death penalty) www.ecpm.org BENEFICIARIES Abolitionist civil society, coalitions of actors against the death penalty and their member Sponsored by organisations working for fundamental rights. Held under Co-funded by The 150 members of the World Coalition Against the Death Penalty. the patronage of the European Union National Human Rights Institutions (NHRIs). -

Download Book

84 823 65 Special thanks to the Independent Institute of Socio-Economic and Political Studies for assistance in getting access to archival data. The author also expresses sincere thanks to the International Consortium "EuroBelarus" and the Belarusian Association of Journalists for information support in preparing this book. Photos by ByMedia.Net and from family albums. Aliaksandr Tamkovich Contemporary History in Faces / Aliaksandr Tamkovich. — 2014. — ... pages. The book contains political essays about people who are well known in Belarus and abroad and who had the most direct relevance to the contemporary history of Belarus over the last 15 to 20 years. The author not only recalls some biographical data but also analyses the role of each of them in the development of Belarus. And there is another very important point. The articles collected in this book were written at different times, so today some changes can be introduced to dates, facts and opinions but the author did not do this INTENTIONALLY. People are not less interested in what we thought yesterday than in what we think today. Information and Op-Ed Publication 84 823 © Aliaksandr Tamkovich, 2014 AUTHOR’S PROLOGUE Probably, it is already known to many of those who talked to the author "on tape" but I will reiterate this idea. I have two encyclopedias on my bookshelves. One was published before 1995 when many people were not in the position yet to take their place in the contemporary history of Belarus. The other one was made recently. The fi rst book was very modest and the second book was printed on classy coated paper and richly decorated with photos. -

Tunisian Democracy Group Wins Nobel Peace Prize 9 October 2015, Bymark Lewis and Karl Ritter

Tunisian democracy group wins Nobel Peace Prize 9 October 2015, byMark Lewis And Karl Ritter Tunisian protesters sparked uprisings across the Arab world in 2011 that overthrew dictators and upset the status quo. Tunisia is the only country in the region to painstakingly build a democracy, involving a range of political and social forces in dialogue to create a constitution, legislature and democratic institutions. "More than anything, the prize is intended as an encouragement to the Tunisian people, who despite major challenges have laid the groundwork for a national fraternity which the committee hopes will serve as an example to be followed by other countries," committee chair Kaci Kullmann Five said. Kaci Kullmann Five, the new head of the Norwegian Nobel Peace Prize Committee, announces the winner of The National Dialogue Quartet is made up of four 2015 Nobel peace prize during a press conference in key organizations in Tunisian civil society: the Oslo, Norway, Friday Oct. 9, 2015. The Norwegian Tunisian General Labour Union; the Tunisian Nobel Committee announced Friday that the 2015 Nobel Confederation of Industry, Trade and Handicrafts; Peace Prize was awarded to the Tunisian National the Tunisian Human Rights League; and the Dialogue Quartet. (Heiko Junge/NTB scanpix via AP) Tunisian Order of Lawyers. Kullmann Five said the prize was for the quartet as a whole, not the four individual organizations. A Tunisian democracy group won the Nobel Peace Prize on Friday for its contributions to the first and The decision came as a surprise to many, with most successful Arab Spring movement. speculation having focused on Europe's migrant crisis or the Iran-U.S.