Mahadev Govind Ranade and the Indian Social Conference

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Ñisforuol NDIH'

./l . l'e-¡c .."$*{fr.n;iT " a^ã*'.t't ç1' """'" A ñisforuol NDIH' Hermann Kulke and Dietmar Rothermund Ël I-ondon and New York f røeo] i i f The Freedom Movement and the partition of India 277 I The Freedom 't Movement and the a solidarity based on a glorious past. This solidarity 7 .{ traditionalism became Partition of India i a major feature of Indian nationalism - and as it was based on Hindu v traditions, it excluded the Muslims. i The Muslims were suspicious of this neo-Hinduism and even distrusted iq I its profession of religious universalism. The emphasis on the equality F i: of all religions was seen as particularly t a subtle threat to Islamic iden- tity. ! But while such trends among the educated Hindu elite were merely The Indian Freedom Movement i suspect to the Muslims, more popular movements of Hindu solidarity ,i - such as the cow-protection movement in Northern India _ were The challenge of imperial rule produced India's nationalism, which raised ''' positively resented by them as a direct attack on their own religious prac- its head rather early in the nineteenth century. Among the new educated i tices, which included cow-slaughter at certain religious fesiivals. the elite there were some critical intenectuars lookeã i wlo upon foreign rule i Hindi-urdu controversy in Northern India added additional fuel to the as a transient phenomenon. As earry as ; lg49 Gopal i{ari Desãmukh ! fire of communal conflict. The Hindus asked only for equal recognition praised American democracy in a Marathi newspaper and predicted that of their language Hindi, written in Devanagari script as a language the Indians would emulate the American I - - revolutionaries ànd drive out permitted in the courts of law, where so far urdu written in Nastaliq the British. -

Indian Political Economy Reading List Maria BACH

Indian Political Economy Reading List Maria BACH Indian Political Economy Maria Bach 13 & 14 November 2017 Reading List Core Readings for Lecture, 13 November 2017 Secondary Sources Omkarnath, G. 2016. “Indian Development Thinking” in Reinert, E.S., Ghosh, J. and Kattel, R. eds., 2016. Handbook of Alternative Theories of Economic Development. Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 212-227. Core Readings for Seminar, 14 November 2017 Primary Sources Dutt, R. C. 1901. Indian Famines, Their Causes and Prevention Westminster. London: P. S. King & Son. Sen, A. 1981. Poverty and famines: an essay on entitlement and deprivation. Oxford university press. Chapters 1 (pp. 1-8), 5 (pp. 45-51), & 6 (pp. 52-85). Further Reading Secondary Sources Adams, J. 1971. “The Institutional Economics of Mahadev Govind Ranade”. Journal of Economic Issues, 5(2), 80-92. Dasgupta, A. K. 2002. History of Indian Economic Thought, London: Routledge. Dutt, S. C. 1934. Conflicting tendencies in Indian economic thought. Calcutta: NM Ray- Chowdhury and Company. Gallagher, R. 1988. “M. G. Ranade and the Indian system of political economy”, Executive Intelligence Review, (May 27) 15(22): pp. 11-15. 1 Indian Political Economy Reading List Maria BACH Ganguli, B.N. 1977. Indian Economic Thought: Nineteenth Century Perspectives. New Delhi: Tata. Gopalakrishnan, P. K. 1954. Development of Economic Ideas in India, 1880-1914. People's Publishing House: Institute of social studies. Goswami, M. 2004. Producing India: From Colonial Economy to National Space. USA: The University of Chicago Press. Gupta, J.N., 1911. Life and Work of Romesh Chunder Dutt, with an Introd. by His Highness the Maharaja of Baroda. -

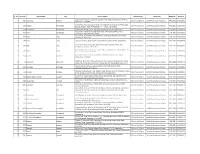

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email Id Remarks 9421864344 022 25401313 / 9869262391 Bhaveshwarikar

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 10001 SALPHALE VITTHAL AT POST UMARI (MOTHI) TAL.DIST- Male DEFAULTER SHANKARRAO AKOLA NAME REMOVED 444302 AKOLA MAHARASHTRA 10002 JAGGI RAMANJIT KAUR J.S.JAGGI, GOVIND NAGAR, Male DEFAULTER JASWANT SINGH RAJAPETH, NAME REMOVED AMRAVATI MAHARASHTRA 10003 BAVISKAR DILIP VITHALRAO PLOT NO.2-B, SHIVNAGAR, Male DEFAULTER NR.SHARDA CHOWK, BVS STOP, NAME REMOVED SANGAM TALKIES, NAGPUR MAHARASHTRA 10004 SOMANI VINODKUMAR MAIN ROAD, MANWATH Male 9421864344 RENEWAL UP TO 2018 GOPIKISHAN 431505 PARBHANI Maharashtra 10005 KARMALKAR BHAVESHVARI 11, BHARAT SADAN, 2 ND FLOOR, Female 022 25401313 / bhaveshwarikarmalka@gma NOT RENEW RAVINDRA S.V.ROAD, NAUPADA, THANE 9869262391 il.com (WEST) 400602 THANE Maharashtra 10006 NIRMALKAR DEVENDRA AT- MAREGAON, PO / TA- Male 9423652964 RENEWAL UP TO 2018 VIRUPAKSH MAREGAON, 445303 YAVATMAL Maharashtra 10007 PATIL PREMCHANDRA PATIPURA, WARD NO.18, Male DEFAULTER BHALCHANDRA NAME REMOVED 445001 YAVATMAL MAHARASHTRA 10008 KHAN ALIMKHAN SUJATKHAN AT-PO- LADKHED TA- DARWHA Male 9763175228 NOT RENEW 445208 YAVATMAL Maharashtra 10009 DHANGAWHAL PLINTH HOUSE, 4/A, DHARTI Male 9422288171 RENEWAL UP TO 05/06/2018 SUBHASHKUMAR KHANDU COLONY, NR.G.T.P.STOP, DEOPUR AGRA RD. 424005 DHULE Maharashtra 10010 PATIL SURENDRANATH A/P - PALE KHO. TAL - KALWAN Male 02592 248013 / NOT RENEW DHARMARAJ 9423481207 NASIK Maharashtra 10011 DHANGE PARVEZ ABBAS GREEN ACE RESIDENCY, FLT NO Male 9890207717 RENEWAL UP TO 05/06/2018 402, PLOT NO 73/3, 74/3 SEC- 27, SEAWOODS, -

Discrimination in an Irrigation Project

QUITY CCESS AND LLOCATION functions. The WRD is supposed to allo- E , A A cate water and supply it to the WUA keeping in mind the ratio of the WUA’s operation area to the total culturable command area Discrimination in (CCA) of the project as per seasonal quotas fixed, and water availability in normal year. This is indicated in the agreement. an Irrigation Project The WUAs in turn are expected to allocate and supply water to farmers, maintain the system and recover the water fees from the Rising population and over-exploitation of groundwater for farmers. The association has to pay water irrigation has aggravated conflict among farmers located at the upper bills as per the volumetric rates fixed by reaches and the tail end of the Palkhed canal system of the Upper the Maharashtra government for different Godavari project of Maharashtra. The formation of water users’ seasons. The WUA has the freedom to associations did alleviate the conflict to some degree, but there grow any crops within the sanctioned quota. continues to be disagreement between the government’s water department and the WUAs on the terms of allocation and other measures. PIM Forces the Issue This process provided some solutions S N LELE, R K PATIL ever planned, frequent water release for for reliable, equitable and timely supply this purpose has also led to much greater of available water to all the farmers in the he Upper Godavari Irrigation seepage and loss through evaporation, command area. Under the PIM, the WUAs Project in Nashik district, reducing the water available for irrigation have to sign a memorandum of under- TMaharashtra, is a multi-storage, by larger amounts than what is apparent. -

Sr. No. Branch ID Branch Name City Branch Address Branch Timing Weekly Off Micrcode Ifsccode 1 1492 Paratwada Achalpur Upper

Sr. No. Branch ID Branch Name City Branch Address Branch Timing Weekly Off MICRCode IFSCCode Upper Ground Floor, "Dr. Deshmukh Complex", Main Road, Paratwada Dist: Amravati, 1 1492 Paratwada Achalpur 9:30 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. 2nd & 4th Saturday and Sunday 444211052 UTIB0001492 Maharashtra , Pin 444805 Ground floor, Shop no.1,2,3,8,9,and 10, R. K .Bungalow, Plot no 12, Near Ambika Nagar, 2 3766 Kedgaon Ahmednagar 9:30 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. 2nd & 4th Saturday and Sunday 414211005 UTIB0003766 Bus Stop, Kedgaon (Devi), Ahmednagar, Pin – 414005 , Maharashtra 3 215 Ahmednagar Ahmednagar Hotel Sanket Complex, 189/6, Tilak Road, Ahmednagar 414 001, Maharashtra 9:30 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. 2nd & 4th Saturday and Sunday 414211002 UTIB0000215 Ground floor, Krishna Kaveri, Nagar-Shirdi Road, Near Zopadi Canteen, Savedi, 4 1853 Savedi Ahmednagar 9:30 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. 2nd & 4th Saturday and Sunday 414211003 UTIB0001853 Ahmednagar, Maharashtra, Pin 414003 Ground Floor, Lohkare Plaza, Mahaveer Path, A/P-Akluj, Tal-Malshiras, Dist. Solapur, 5 1256 Akluj Akluj 9:30 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. 2nd & 4th Saturday and Sunday 413211452 UTIB0001256 Maharashtra , Pin 413101 6 749 Akola Akola Akola, Maharashtra,‘Khatri House’,Amankha Plot Road,Akola 444001, Maharashtra 9:30 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. 2nd & 4th Saturday and Sunday 444211002 UTIB0000749 Ground Floor, Satya Sankul, Near Walshinghe Hospital, Hiwarkhed Road, Akot, 7 2666 Akot Akola 9:30 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. 2nd & 4th Saturday and Sunday 444211152 UTIB0002666 Dist. -

1. SHRI. BAKERAO TUKARAM DHEMSE. Chinchkhed Road, Pimpalgaon Baswant, Taluka Niphad, District Nashik-422209

BEFORE THE NATIONAL GREEN TRIBUNAL (WESTERN ZONE) BENCH, PUNE APPLICATION NO.16 OF 2014 with APPLICATION NO.58 (THC) OF 2014 CORAM: HON’BLE SHRI JUSTICE V.R. KINGAONKAR (Judicial Member) HON’BLE DR. AJAY A.DESHPANDE (Expert Member) In the matter of: 1. SHRI. BAKERAO TUKARAM DHEMSE. Chinchkhed Road, Pimpalgaon Baswant, Taluka Niphad, District Nashik-422209. 2. SHRI. NIRMAL KASHINATH KAJALE, Both of residents of village Pathardi, Dist. Nashik. ……… APPLICANTS VERSUS 1. THE MUNICIPAL CORPORTON, Nasik- through its Commissioner, Rajiv Gandhi Bhavan, Tilakwadi, Nashik. 2. The STATE OF MAHARASHTRA, Through the Secretary, Department of Public Health & Environment, Mantralaya, Mumbai-400 032. 3. THE MAHARASHTRA POLLUTION CONTROL BOARD, Through its Regional Office, “Udyog Bhavan” 1st Floor, Trimbak Road, MIDC Compound, Satpur, Nashik-422006. (J) Application No.16 of 2014 1 of 22 Application No.58(THC) 2014 4. NATIONAL ENVIRONMENT ENGINEERING, Research Institute, Nehru Marg, Nagpur-440 020. 5. THE COLLECTOR OF NASHIK, Shri. Vilas Patil Old Agra Road, Near CBS, Nashik-422009. ………RESPONDENTS APPLICATION NO.58 (THC) OF 2014 In the matter of: 1. NARAYAN S/O NAMDEO YADAV, Age: Adult, Occ: Proprietor of Saish Industries & Social Worker R/o-A-3/2, Rathchakra Society Indira Nagar, Nasik . 2. JAGDISH S/O KONDAJI NAVALE, Age: Adult, Occ: Hotel Owner & Service, R/o- Pathardi Fata, Bombay-Agra Road, Nasik. ………APPLICANTS VERSUS 1. THE MUNICIPAL CORPORTON, Nasik- through its Commissioner, Rajiv Gandhi Bhavan, Tilakwadi, Nashik. 2. THE MAHARASHTRA POLLUTION CONTROL BOARD, Through its Regional Office, “Udyog Bhavan” 1st Floor, Trimbak Road, MIDC Compound, Satpur, Nashik-422006. 3. THE COLLECTOR OF NASHIK, Shri. -

Chapter-7 Profile of Nashik District

Chapter-7 Profile of Nashik District 7.1 A Historical Perspective : Nashik has a personaUty of its own, due to its mythological, historical, social and cultural importance. The city is situated on the banks of the Godavari River, making it one of the holiest places for Hindus all over the world. Nashik has a rich historical past, as the mythology has it that Lord Rama, the King of Ayodhya, made Nashik his adobe during his 14 years in exile. At the same place Lord Laxman, by the wish of Lord Rama, cut the nose of 'Shurpnakha' and thus this city was named as 'Nashik'. In Kritayuga, Nashik was 'Trikantak', 'Janasthana' in Dwaparyuga and later in Kuliyuga it became 'Navashikh' or 'Nashik'. Renowned poets like Valmiki, Kalidas and Bhavabhooti have paid rich tributes here. Nashi in 150 BC was believed to be the country's largest market place. From 1487 AD this province came under the rule of Mughals and was known as 'Gulchanabad'. It was also home of Emperor Akbar and he has written at length about Nashik in 'Ein-e-Akbari'. It was also known as the 'Land of the brave' during the regime of Chhatrapati ShivajiMaharaj. 7.1.1 Ramayana Period : No one knows when the city of Nashik came into existence. It is stated to have been present even in the Stone Age. Lord Ramchandra along with wife Sita and brother Laxman settled down in Nashik for the major time of their 'Vanwasa'. According to the mythology, Laxman cut the nose ('Nasika' in Sanskrita) of 'Shurpanakha' and hence the city got the name 'Nashik'. -

Dadabhai Naoroji

UNIT – IV POLITICAL THINKERS DADABHAI NAOROJI Dadabhai Naoroji (4 September 1825 – 30 June 1917) also known as the "Grand Old Man of India" and "official Ambassador of India" was an Indian Parsi scholar, trader and politician who was a Liberal Party member of Parliament (MP) in the United Kingdom House of Commons between 1892 and 1895, and the first Asian to be a British MP, notwithstanding the Anglo- Indian MP David Ochterlony Dyce Sombre, who was disenfranchised for corruption after nine months. Naoroji was one of the founding members of the Indian National Congress. His book Poverty and Un-British Rule in India brought attention to the Indian wealth drain into Britain. In it he explained his wealth drain theory. He was also a member of the Second International along with Kautsky and Plekhanov. Dadabhai Naoroji's works in the congress are praiseworthy. In 1886, 1893, and 1906, i.e., thrice was he elected as the president of INC. In 2014, Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg inaugurated the Dadabhai Naoroji Awards for services to UK-India relations. India Post depicted Naoroji on stamps in 1963, 1997 and 2017. Contents 1Life and career 2Naoroji's drain theory and poverty 3Views and legacy 4Works Life and career Naoroji was born in Navsari into a Gujarati-speaking Parsi family, and educated at the Elphinstone Institute School.[7] He was patronised by the Maharaja of Baroda, Sayajirao Gaekwad III, and started his career life as Dewan (Minister) to the Maharaja in 1874. Being an Athornan (ordained priest), Naoroji founded the Rahnumai Mazdayasan Sabha (Guides on the Mazdayasne Path) on 1 August 1851 to restore the Zoroastrian religion to its original purity and simplicity. -

Zonal Disaster Management Plan 2019

201920162018 FOREWORD I am happy to note that the Safety Department of Central Railway is bringing out a revised edition of the Zonal Disaster Management Plan of Central Railway for the year 2019. Earlier, a ‘Disaster’ on the Railway meant only a serious train accident. The situation has now changed with the promulgation of Disaster Management Act in the year 2005. Under this act, the word ‘Disaster’ includes natural calamities like earthquake, floods, etc., and also man- made disasters like terrorist acts through bomb blasts, chemical, nuclear and biological disasters. Basically, a ‘Disaster’ is a situation which is beyond the coping capacity of Railways and would require large scale assistance from other agencies. Arising out of DM Act, Government of India has formed a National Crisis Management Committee (NCMC). Thus, Central Management Groups (CMG’s) have been formed in each Ministry, including Railway Ministry, under NCMC. An Integrated Operation Centre (IOC) has been opened in the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) to handle disaster situation 24 x 7. All concerned Ministries/Departments/Organisations/Agencies will report events to IOC. This Zonal Disaster Management Plan includes brief particulars of these Committees/Groups. A new training methodology and schedule decided by the Board is also included in this Disaster Management plan which will be helpful to strengthen and revamp the Training on Disaster Management being imparted to several tiers of railway officials through Railway Training Institutes. This Plan provides for a structured means of response to any accident or calamity that involves the Railways and ensures that resources of State Administration, National Disaster Response Force and others quickly become available for deployment. -

Age Sex Template 07 Sep 21

AGE SEX TEMPLATE 07 SEP 21 SRNO AGE SEX ADDRESS AREA BLOCK LAB 1 32 F Vanpat Malegaon MMC Mmc RAT 3 Sumati Soc Sharanpur Road 2 16 M Shastri Nagar Opp Kulkarni NMC Nmc AK LAB Garden Gole Colony Nashik Flat No 7 Tulshi Hig Pathardi 3 22 M Road Dnyaneshwar Nagar NMC Nmc AK LAB Pathardi Nashik Plot No 22 Sukhrang Vihar 4 25 F Wadala Pathardi Road Near NMC Nmc AK LAB Nersingh College Indira Nagar 5 20 F Borgad Nashik NMC Nmc NMC LAB 6 20 F Nashik Road NMC Nmc NMC LAB 7 26 F Navshya Ganpati NMC Nmc NMC LAB 8 46 F Navshya Ganpati NMC Nmc NMC LAB Near Gani Hall Kathada 9 32 M NMC Nmc NMC LAB Nashik 10 38 M Panchavati Nashik NMC Nmc NMC LAB Nashik Road Police Station 11 41 M NMC Nmc DH VRDL Nashik 3 Saidwar Rowhouses 12 20 M Sambhaji Chowk Untawadi NMC Nmc DATAR Road Nashik Akshardham Gangapur Road 13 33 M Aakashwani Tower Datey NMC Nmc DATAR Nagar Atma Malik Bunglow Satpur 14 23 F Link Road Near Sadhna Misal NMC Nmc DATAR Bardan Phata Bunglow No-6 Shramik 15 11 M Society No-1 Gangapur Road NMC Nmc DATAR Akashwani Tower Nashik Flat No 2 Shandar Appartment 16 41 M Pumping Station Road Behind NMC Nmc DATAR Vidhaya Vikas Hospital Flat No 2 Shandar Appartment 17 11 M Pumping Station Road Behind NMC Nmc DATAR Vidhaya Vikas Hospital Flat No 2 Shandar Appartment 18 4 M Pumping Station Road Behind NMC Nmc DATAR Vidhaya Vikas Hospital Flat No 4 Shree Valabh Apt 19 38 F Shraddha Vihar Indira Nagar NMC Nmc DATAR Near Aashirwad Narshing Plot No 42 43 Swapna Purti 20 36 M Niwas Gangapur Satpur Road NMC Nmc DATAR Near Motiwala Medical Plot No 88 Lane No 2 -

Role of Congress in the Emancipation of Untouchables of India: Perspective of Dr

International Journal of Academic Research and Development International Journal of Academic Research and Development ISSN: 2455-4197, Impact Factor: RJIF 5.22 www.newresearchjournal.com/academic Volume 1; Issue 5; May 2016; Page No. 87-90 Role of congress in the emancipation of untouchables of India: Perspective of Dr. B. R. Ambedkar Dr. SK Bhadarge Head, History Department, B. N.N. College, Bhiwandi, Maharashtra, India Abstract Dr. Ambedker’s concept of social justice stands for the liberty, equality and fraternity of all human beings. Dr. Ambedkar a rationalist and humanist, did not approve any type of hupocrisy, injustice and exploitation of man by man in the name of religion. He critics on Indian society and come to the conclusion that caste system as the greatest evil of Hindu religion. Indian National congress was established in the year 1885 and she started the political movement throughout in India. Some of the congress leader like Mahadev Govind Randade believed that without social change in our society there is no use to run the political movement in India. With his efforts social conference was established in the year 1887 for the social movement but some orthodoxy congress leader object to Ranade to run the social activities under the umbrella of Congress. Under the president of Mrs. Annie Besant in the year 1917 resolution was passed regarding the untouchbility. It means now congress was thinking that, untouchability should remove from the society. But what exactly constructive work done by congress to remove the untochability from the society? How much congress was succeeded to remove untochbility from the society that has been criticized by Dr. -

New Insights Into the Debates on Rural Indebtedness in 19Th Century Deccan

SPECIAL ARTICLE New Insights into the Debates on Rural Indebtedness in 19th Century Deccan Parimala V Rao The peasantry in the Deccan suffered from widespread n the pre-colonial Deccan of the 17th century the peasantry, indebtedness during the 19th century. In March 1881, as far as their liability to the state was concerned, comprised two categories – those who paid little or no rent to the State after touring the rural areas of Poona and Ahmadnagar I and those who paid high rent. The first category was dominated districts, which were still recovering from the by affluent Brahmins and elite Marathas who owned most of devastations caused by famine and the credit crunch the fertile lands as rent free or inam lands. The inams were land followed by the peasant revolt of 1876-79, grants often for the services rendered to the state. In the Deccan, villages and at times groups of villages were held as inam. In Mahadev Govind Ranade proposed the establishment of the Badami taluka of Belgaum district 76 complete villages and agricultural-shetkari banks. The nationalists led by 42% of arable land in the remaining 151 villages were held as Bal Gangadhar Tilak opposed the proposal. This article inam.1 So what was available for cultivation to the second cate- explores the debates on peasant indebtedness and the gory of tax paying peasants called mirasdars (holder of hereditary rights) and uparis (without hereditary rights) was intervention of nationalists on behalf of the less fertile land. This category comprised a few landlords who moneylenders to oppose even limited measures to assist were peasants from the Maratha-Kunbi castes and the rest owned peasants in the rural economy.