A Ñisforuol NDIH'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INDIAN NATIONAL CONGRESS 1885-1947 Year Place President

INDIAN NATIONAL CONGRESS 1885-1947 Year Place President 1885 Bombay W.C. Bannerji 1886 Calcutta Dadabhai Naoroji 1887 Madras Syed Badruddin Tyabji 1888 Allahabad George Yule First English president 1889 Bombay Sir William 1890 Calcutta Sir Pherozeshah Mehta 1891 Nagupur P. Anandacharlu 1892 Allahabad W C Bannerji 1893 Lahore Dadabhai Naoroji 1894 Madras Alfred Webb 1895 Poona Surendranath Banerji 1896 Calcutta M Rahimtullah Sayani 1897 Amraoti C Sankaran Nair 1898 Madras Anandamohan Bose 1899 Lucknow Romesh Chandra Dutt 1900 Lahore N G Chandravarkar 1901 Calcutta E Dinsha Wacha 1902 Ahmedabad Surendranath Banerji 1903 Madras Lalmohan Ghosh 1904 Bombay Sir Henry Cotton 1905 Banaras G K Gokhale 1906 Calcutta Dadabhai Naoroji 1907 Surat Rashbehari Ghosh 1908 Madras Rashbehari Ghosh 1909 Lahore Madanmohan Malaviya 1910 Allahabad Sir William Wedderburn 1911 Calcutta Bishan Narayan Dhar 1912 Patna R N Mudhalkar 1913 Karachi Syed Mahomed Bahadur 1914 Madras Bhupendranath Bose 1915 Bombay Sir S P Sinha 1916 Lucknow A C Majumdar 1917 Calcutta Mrs. Annie Besant 1918 Bombay Syed Hassan Imam 1918 Delhi Madanmohan Malaviya 1919 Amritsar Motilal Nehru www.bankersadda.com | www.sscadda.com| www.careerpower.in | www.careeradda.co.inPage 1 1920 Calcutta Lala Lajpat Rai 1920 Nagpur C Vijaya Raghavachariyar 1921 Ahmedabad Hakim Ajmal Khan 1922 Gaya C R Das 1923 Delhi Abul Kalam Azad 1923 Coconada Maulana Muhammad Ali 1924 Belgaon Mahatma Gandhi 1925 Cawnpore Mrs.Sarojini Naidu 1926 Guwahati Srinivas Ayanagar 1927 Madras M A Ansari 1928 Calcutta Motilal Nehru 1929 Lahore Jawaharlal Nehru 1930 No session J L Nehru continued 1931 Karachi Vallabhbhai Patel 1932 Delhi R D Amritlal 1933 Calcutta Mrs. -

Mahadev Govind Ranade and the Indian Social Conference

MAHADEV GOVIND RANADE AND THE INDIAN SOCIAL CONFERENCE DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQU1F?EMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF llasttr of f I)ilo£(opf)P IN POLITICAL SCIENCE BY MOHAMMAD ABID ANSARI UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF PROF. M. SUBRAHMANYAM DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) ie96 \\-:\' .^O at«» \.;-2>^-^9 5^ ':•• w • r.,a DS2982 DEDICATED TO MY MOTHER Prof. M. subrahmanyam Department o1 Political Science Aligarh Muslim University Phones {Internal: z^i^\CI'Birm,n Aligarh—202 002 365 Office Oated... CERTIFICATE This is to certify that Mohammad Abid An sari has ccxnpleted his dissertation on "Mahadev Govind Ranade and the Indian Social Conference" under ray supervision. It is his original contribution. In ray opinion this dissertation is suitable for submission for the award of Master of Philosophy in Political science. .J >'^ >->^ Prof. M. subrahnanyam CONTENTS PAGE NO. PREFACE I - III ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS IV- V CHAPTERS I GENESIS OF SOCIAL REFORM IN INDIA 1-24 II A BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH 25-49 III THE SOCIAL REFORMER 50-83 IV RANADE AND THE INDIAN SOCIAL CONFERENCE 84-98 V CONCLUSION 99 - 109 BIBLIOGRAPHY I - IV ** * PREFACE The Indian Renaissance of the nineteenth and the twentieth centuries Is one of the most significant movements of Indian history. The nineteenth century« rationalisn, and htunanlsm had influenced* religions, science* philosophy* politics* economics* law and morality* The English education Inspired a new spirit and pregresaive ideas. Thus a number of schools -

The Ideological Differences Between Moderates and Extremists in the Indian National Movement with Special Reference to Surendranath Banerjea and Lajpat Rai

1 The Ideological Differences between Moderates and Extremists in the Indian National Movement with Special Reference to Surendranath Banerjea and Lajpat Rai 1885-1919 ■by Daniel Argov Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, in the University of London* School of Oriental and African Studies* June 1964* ProQuest Number: 11010545 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11010545 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 2 ABSTRACT Surendranath Banerjea was typical of the 'moderates’ in the Indian National Congress while Lajpat Rai typified the 'extremists'* This thesis seeks to portray critical political biographies of Surendranath Banerjea and of Lajpat Rai within a general comparative study of the moderates and the extremists, in an analysis of political beliefs and modes of political action in the Indian national movement, 1883-1919* It attempts to mirror the attitude of mind of the two nationalist leaders against their respective backgrounds of thought and experience, hence events in Bengal and the Punjab loom larger than in other parts of India* "The Extremists of to-day will be Moderates to-morrow, just as the Moderates of to-day were the Extremists of yesterday.” Bal Gangadhar Tilak, 2 January 190? ABBREVIATIONS B.N.]T.R. -

Indian Political Economy Reading List Maria BACH

Indian Political Economy Reading List Maria BACH Indian Political Economy Maria Bach 13 & 14 November 2017 Reading List Core Readings for Lecture, 13 November 2017 Secondary Sources Omkarnath, G. 2016. “Indian Development Thinking” in Reinert, E.S., Ghosh, J. and Kattel, R. eds., 2016. Handbook of Alternative Theories of Economic Development. Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 212-227. Core Readings for Seminar, 14 November 2017 Primary Sources Dutt, R. C. 1901. Indian Famines, Their Causes and Prevention Westminster. London: P. S. King & Son. Sen, A. 1981. Poverty and famines: an essay on entitlement and deprivation. Oxford university press. Chapters 1 (pp. 1-8), 5 (pp. 45-51), & 6 (pp. 52-85). Further Reading Secondary Sources Adams, J. 1971. “The Institutional Economics of Mahadev Govind Ranade”. Journal of Economic Issues, 5(2), 80-92. Dasgupta, A. K. 2002. History of Indian Economic Thought, London: Routledge. Dutt, S. C. 1934. Conflicting tendencies in Indian economic thought. Calcutta: NM Ray- Chowdhury and Company. Gallagher, R. 1988. “M. G. Ranade and the Indian system of political economy”, Executive Intelligence Review, (May 27) 15(22): pp. 11-15. 1 Indian Political Economy Reading List Maria BACH Ganguli, B.N. 1977. Indian Economic Thought: Nineteenth Century Perspectives. New Delhi: Tata. Gopalakrishnan, P. K. 1954. Development of Economic Ideas in India, 1880-1914. People's Publishing House: Institute of social studies. Goswami, M. 2004. Producing India: From Colonial Economy to National Space. USA: The University of Chicago Press. Gupta, J.N., 1911. Life and Work of Romesh Chunder Dutt, with an Introd. by His Highness the Maharaja of Baroda. -

Indian National Congress Sessions

Indian National Congress Sessions INC sessions led the course of many national movements as well as reforms in India. Consequently, the resolutions passed in the INC sessions reflected in the political reforms brought about by the British government in India. Although the INC went through a major split in 1907, its leaders reconciled on their differences soon after to give shape to the emerging face of Independent India. Here is a list of all the Indian National Congress sessions along with important facts about them. This list will help you prepare better for SBI PO, SBI Clerk, IBPS Clerk, IBPS PO, etc. Indian National Congress Sessions During the British rule in India, the Indian National Congress (INC) became a shiny ray of hope for Indians. It instantly overshadowed all the other political associations established prior to it with its very first meeting. Gradually, Indians from all walks of life joined the INC, therefore making it the biggest political organization of its time. Most exam Boards consider the Indian National Congress Sessions extremely noteworthy. This is mainly because these sessions played a great role in laying down the foundational stone of Indian polity. Given below is the list of Indian National Congress Sessions in chronological order. Apart from the locations of various sessions, make sure you also note important facts pertaining to them. Indian National Congress Sessions Post Liberalization Era (1990-2018) Session Place Date President 1 | P a g e 84th AICC Plenary New Delhi Mar. 18-18, Shri Rahul Session 2018 Gandhi Chintan Shivir Jaipur Jan. 18-19, Smt. -

RTI Handbook

PREFACE The Right to Information Act 2005 is a historic legislation in the annals of democracy in India. One of the major objective of this Act is to promote transparency and accountability in the working of every public authority by enabling citizens to access information held by or under the control of public authorities. In pursuance of this Act, the RTI Cell of National Archives of India had brought out the first version of the Handbook in 2006 with a view to provide information about the National Archives of India on the basis of the guidelines issued by DOPT. The revised version of the handbook comprehensively explains the legal provisions and functioning of National Archives of India. I feel happy to present before you the revised and updated version of the handbook as done very meticulously by the RTI Cell. I am thankful to Dr.Meena Gautam, Deputy Director of Archives & Central Public Information Officer and S/Shri Ashok Kaushik, Archivist and Shri Uday Shankar, Assistant Archivist of RTI Cell for assisting in updating the present edition. I trust this updated publication will familiarize the public with the mandate, structure and functioning of the NAI. LOV VERMA JOINT SECRETARY & DGA Dated: 2008 Place: New Delhi Table of Contents S.No. Particulars Page No. ============================================================= 1 . Introduction 1-3 2. Particulars of Organization, Functions & Duties 4-11 3. Powers and Duties of Officers and Employees 12-21 4. Rules, Regulations, Instructions, 22-27 Manual and Records for discharging Functions 5. Particulars of any arrangement that exist for 28-29 consultation with or representation by the members of the Public in relation to the formulation of its policy or implementation thereof 6. -

Important Indian National Congress Sessions

Important Indian National Congress Sessions drishtiias.com/printpdf/important-indian-national-congress-sessions Introduction The Indian National Congress was founded at Bombay in December 1885. The early leadership – Dadabhai Naoroji, Pherozeshah Mehta, Badruddin Tyabji, W.C. Bonnerji, Surendranath Banerji, Romesh Chandra Dutt, S. Subramania Iyer, among others – was largely from Bombay and Calcutta. A retired British official, A.O. Hume, also played a part in bringing Indians from the various regions together. Formation of Indian National Congress was an effort in the direction of promoting the process of nation building. In an effort to reach all regions, it was decided to rotate the Congress session among different parts of the country. The President belonged to a region other than where the Congress session was being held. Sessions First Session: held at Bombay in 1885. President: W.C. Bannerjee Formation of Indian National Congress. Second Session: held at Calcutta in 1886. President: Dadabhai Naoroji Third Session: held at Madras in 1887. President: Syed Badruddin Tyabji, first muslim President. Fourth Session: held at Allahabad in 1888. President: George Yule, first English President. 1896: Calcutta. President: Rahimtullah Sayani National Song ‘Vande Mataram’ sung for the first time by Rabindranath Tagore. 1899: Lucknow. President: Romesh Chandra Dutt. Demand for permanent fixation of Land revenue 1901: Calcutta. President: Dinshaw E.Wacha First time Gandhiji appeared on the Congress platform 1/4 1905: Benaras. President: Gopal Krishan Gokhale Formal proclamation of Swadeshi movement against government 1906: Calcutta. President: Dadabhai Naoroji Adopted four resolutions on: Swaraj (Self Government), Boycott Movement, Swadeshi & National Education 1907: Surat. President: Rash Bihari Ghosh Split in Congress- Moderates & Extremist Adjournment of Session 1910: Allahabad. -

Dadabhai Naoroji

UNIT – IV POLITICAL THINKERS DADABHAI NAOROJI Dadabhai Naoroji (4 September 1825 – 30 June 1917) also known as the "Grand Old Man of India" and "official Ambassador of India" was an Indian Parsi scholar, trader and politician who was a Liberal Party member of Parliament (MP) in the United Kingdom House of Commons between 1892 and 1895, and the first Asian to be a British MP, notwithstanding the Anglo- Indian MP David Ochterlony Dyce Sombre, who was disenfranchised for corruption after nine months. Naoroji was one of the founding members of the Indian National Congress. His book Poverty and Un-British Rule in India brought attention to the Indian wealth drain into Britain. In it he explained his wealth drain theory. He was also a member of the Second International along with Kautsky and Plekhanov. Dadabhai Naoroji's works in the congress are praiseworthy. In 1886, 1893, and 1906, i.e., thrice was he elected as the president of INC. In 2014, Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg inaugurated the Dadabhai Naoroji Awards for services to UK-India relations. India Post depicted Naoroji on stamps in 1963, 1997 and 2017. Contents 1Life and career 2Naoroji's drain theory and poverty 3Views and legacy 4Works Life and career Naoroji was born in Navsari into a Gujarati-speaking Parsi family, and educated at the Elphinstone Institute School.[7] He was patronised by the Maharaja of Baroda, Sayajirao Gaekwad III, and started his career life as Dewan (Minister) to the Maharaja in 1874. Being an Athornan (ordained priest), Naoroji founded the Rahnumai Mazdayasan Sabha (Guides on the Mazdayasne Path) on 1 August 1851 to restore the Zoroastrian religion to its original purity and simplicity. -

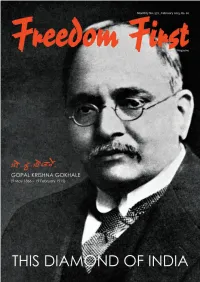

Gokhale and Gandhi - Their Second Meeting Birth Centenary Lectures Which Were Later Published Under Prabha Ravi Shankar 14 the Title Gokhale and Modern India

NEW PUBLICATIONS For a brief description of these publications turn to page 34. For copies, get in touch with us at Freedom First, 3rd floor, Army and Navy Building, 148 Mahatma Gandhi Road, Mumbai 4000001. You can also email us at [email protected] or phone us at 022-22843416 or 022-66396366. 2 Freedom First February 2015 www.freedomfirst.in Freedom First The Liberal Magazine – 63rd Year of Publication Between Ourselves No.572 February 2015 GOPAL KRISHNA GOKHALE Contents 1866 - 1915 New Publications 2 Gopal Krishna Gokhale was the founder of the Servants Between Ourselves 3 of India Society, President of the Indian National Congress The Legacy of Gopal Krishna Gokhale and a member of the Imperial Legislative Council. His Death Centenary Year, February 19, 1915-2014, was commemorated Introduction by several organisations. Among them the Deccan A. B. Shah 4 Education Society, Servants of India Society, Gokhale Laying the Foundation for a Modern India Institute of Politics and Economics, Indian Committee for S. P. Aiyar 4 Cultural Freedom, Project for Economic, Indian Secular His Relevance Today Society and Mani Bhavan Gandhi Sangrahalaya. Aroon Tikekar 8 His Achievements On his birth centenary in May 1966, the Indian Committee Sunil Gokhale 11 for Cultural Freedom (ICCF) had organised a series of three Gokhale and Gandhi - Their Second Meeting Birth Centenary Lectures which were later published under Prabha Ravi Shankar 14 the title Gokhale and Modern India. Sir Pherozeshah Mehta’s Tribute Godrej N. Dotivala 16 Forty eight years on, on November 15, 2014, the ICCF, in Some Contemporaries of Gokhale in Poona association with the Project for Economic Education, the R. -

Role of Congress in the Emancipation of Untouchables of India: Perspective of Dr

International Journal of Academic Research and Development International Journal of Academic Research and Development ISSN: 2455-4197, Impact Factor: RJIF 5.22 www.newresearchjournal.com/academic Volume 1; Issue 5; May 2016; Page No. 87-90 Role of congress in the emancipation of untouchables of India: Perspective of Dr. B. R. Ambedkar Dr. SK Bhadarge Head, History Department, B. N.N. College, Bhiwandi, Maharashtra, India Abstract Dr. Ambedker’s concept of social justice stands for the liberty, equality and fraternity of all human beings. Dr. Ambedkar a rationalist and humanist, did not approve any type of hupocrisy, injustice and exploitation of man by man in the name of religion. He critics on Indian society and come to the conclusion that caste system as the greatest evil of Hindu religion. Indian National congress was established in the year 1885 and she started the political movement throughout in India. Some of the congress leader like Mahadev Govind Randade believed that without social change in our society there is no use to run the political movement in India. With his efforts social conference was established in the year 1887 for the social movement but some orthodoxy congress leader object to Ranade to run the social activities under the umbrella of Congress. Under the president of Mrs. Annie Besant in the year 1917 resolution was passed regarding the untouchbility. It means now congress was thinking that, untouchability should remove from the society. But what exactly constructive work done by congress to remove the untochability from the society? How much congress was succeeded to remove untochbility from the society that has been criticized by Dr. -

New Insights Into the Debates on Rural Indebtedness in 19Th Century Deccan

SPECIAL ARTICLE New Insights into the Debates on Rural Indebtedness in 19th Century Deccan Parimala V Rao The peasantry in the Deccan suffered from widespread n the pre-colonial Deccan of the 17th century the peasantry, indebtedness during the 19th century. In March 1881, as far as their liability to the state was concerned, comprised two categories – those who paid little or no rent to the State after touring the rural areas of Poona and Ahmadnagar I and those who paid high rent. The first category was dominated districts, which were still recovering from the by affluent Brahmins and elite Marathas who owned most of devastations caused by famine and the credit crunch the fertile lands as rent free or inam lands. The inams were land followed by the peasant revolt of 1876-79, grants often for the services rendered to the state. In the Deccan, villages and at times groups of villages were held as inam. In Mahadev Govind Ranade proposed the establishment of the Badami taluka of Belgaum district 76 complete villages and agricultural-shetkari banks. The nationalists led by 42% of arable land in the remaining 151 villages were held as Bal Gangadhar Tilak opposed the proposal. This article inam.1 So what was available for cultivation to the second cate- explores the debates on peasant indebtedness and the gory of tax paying peasants called mirasdars (holder of hereditary rights) and uparis (without hereditary rights) was intervention of nationalists on behalf of the less fertile land. This category comprised a few landlords who moneylenders to oppose even limited measures to assist were peasants from the Maratha-Kunbi castes and the rest owned peasants in the rural economy. -

The Evolution of the Professional Structure in Modern India : Older and New Professions in a Changing

C/83-5 THE EVOLUTION OF THE PROFESSIONAL STRUCTURE IN MODERN INDIA: OLDER AND NEW PROFESSIONS IN A CHANGING SOCIETY Rajat Kanta Ray Professor and Head Department of History Presidency College Calcutta, India Center for International Studies Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139 August 1983 ,At Foreword This historical study by Professor Rajat Ray is one of a series which examines the development of professions as a key to understanding the different patterns in the modernization of Asia. In recent years there has been much glib talk about "technology transfers" to the Third World, as though knowledge and skills could be easily packaged and delivered. Profound historical processes were thus made analogous to shopping expeditions for selecting the "appropriate technology" for the country's resources. The MIT Center for International Studies's project on the Modernization of Asia is premised on a different sociology of knowledge. Our assumption is that the knowledge and skills inherent in the modernization processes take on meaningful historical significance only in the context of the emergence of recognizable professions, which are communities of people that share specialized knowledge and skills and seek to uphold standards. It would seem that much that is distinctive in the various ways in which the different Asian societies have modernized can be found by seeking answers to such questions as: which were the earlier professions to be established, and which ones came later? What were the political, social