Snack-Media Platform Market Segmentation Based on User Heterogeneity: a Q-Methodology Approach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Effects of Live Platform Exterior Design on Sustainable

sustainability Article The Effects of Live Platform Exterior Design on Sustainable Impulse Buying: Exploring the Mechanisms of Self-Efficacy and Psychological Ownership Xiaoxiao Gong 1,* , Zuoliang Ye 2, Kuo Liu 1 and Na Wu 3 1 School of Business Administration, Southwestern University of Finance and Economics, Chengdu 611130, China; [email protected] 2 School of International Business, Southwestern University of Finance and Economics, Chengdu 611130, China; [email protected] 3 School of Business Administration, Zhongnan University of Economics and Law, Wuhan 430073, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 1 March 2020; Accepted: 15 March 2020; Published: 19 March 2020 Abstract: The sensory upgrading facilitated by live platforms, such as YouTube Live, Twitch, and Periscope, can facilitate much better interactions and understanding between a product, its brand, and the user. The question of how to enhance sustainable marketing effects using exterior design is currently a major topic in the live streaming marketing sector. The effect of the exterior design of a live platform on the impulse purchases of its consumers has rarely been discussed by academic research. Accordingly, based on the theory of self-determination, this study explored the direct effects of exterior design, self-efficacy, psychological ownership, and impulse buying by using multiple linear regression, and examined the indirect effects of these variables using the structural equation model. In this study, 534 samples were collected from live consumers, and our hypotheses were verified by employing hierarchical regression. As revealed from the results obtained, the self-efficacy and psychological ownership exhibited by consumers exerted synchronous and chain mediating effects on the relationships between the exterior design of the platform and consumer impulse buying. -

BTS, Digital Media, and Fan Culture

19 Hyunshik Ju Sungkyul University, South Korea Premediating a Narrative of Growth: BTS, Digital Media, and Fan Culture This article explores the landscape of fan engagements with BTS, the South Korean idol group. It offers a new approach to studying digital participation in fan culture. Digital fan‐based activity is singled out as BTS’s peculiarity in K‐pop’s history. Grusin’s discussion of ‘premediation’ is used to describe an autopoietic system for the construction of futuristic reality through online communication between BTS and ARMY, as the fans are called. As such, the BTS’s live performance is experienced through ARMY’s premediation, imaging new identities of ARMY as well as BTS. The way that fans engage digitally with BTS’s live performance is motivated by a narrative of growth of BTS with and for ARMY. As an agent of BTS’s success, ARMY is crucial in driving new economic trajectories for performative products and their audiences, radically intervening in the shape and scope of BTS’s contribution to a global market economy. Hunshik Ju graduated with Doctor of Korean Literature from Sogang University in South Korea. He is currently a full‐time lecturer at the department of Korean Literature and Language, Sungkyul University. Keywords: BTS, digital media fan culture, liveness, premediation Introduction South Korean (hereafter Korean) idol group called Bulletproof Boy AScouts (hereafter BTS) delivered a speech at the launch of “Generation Unlimited,” United Nations Children’s Fund’s (UNICEF) new youth agenda, at the United Nations General Assembly in New York on September 24, 2018. In his speech, BTS’s leader Kim Nam Jun (also known as “RM”) stressed the importance of self-love by stating that one must love oneself wholeheartedly regardless of the opinions and judgments of others.1 Such a message was not new to BTS fans, since the group’s songs usually raise concerns and reflections about young people’s personal growth. -

A Conversation Analysis of Facebook Confessions Pages: Identity and Identification

A Conversation Analysis of Facebook Confessions Pages: Identity and Identification Nurul Firdauz Binti Abd Rahman PhD The University of York Sociology September 2018 Abstract How individuals identify each other through digital media and display their claims of knowledge is at the core of this study. This work contributes new insights into how participants accomplished identity work by looking at the conversational resources they use in addressing matters of identity in their interaction. The study draws on Conversation Analysis (CA), particularly conceptual work on membership categorization analysis (MCA) and epistemics for analysis. The findings based on two interrelated aspects of the data taken from Facebook Confession Pages interaction. The first concerns the features of the initial (confessional) message, and the second relates to subsequent responses on the initial message. Close examination of the initial message shows ways that identity work is initiated as it would implicate in that subsequent response messages. Two primary forms of messages were then identified on the basis of person reference: those that inform and those that inquire. In each category, the analysis demonstrates that person reference is used as interactional resource in making an epistemic claim of the referent. The person reference is contextual in that they are locally based and understood within the specific contexts of the message. Thus, it is shown that the employment of person reference in the initial message illustrates the epistemic level that author has with the referent. Accordingly, analysis of the subsequent response messages demonstrated ways in which the identity, as presented in the initial message, is identified. The analysis of the subsequent response messages offers insight into how identity works is accomplished through a collaborative commenter’s epistemic stance. -

State of Video Streaming Apps in Asia Table of Contents

State of Video Streaming Apps in Asia Table of Contents Executive Summary 3 The Dramatic Growth of Video Streaming Apps in APAC 6 Video Streaming Apps’ Continued Momentum in APAC 9 Massive Surge in APAC Video Streaming Apps Usage 13 Monetization of APAC Top Video Apps Soars 18 Lessons From APAC Video Streaming Apps 21 2 Executive Summary ● Video streaming on mobile continues to see incredible growth. Between H1 2015 and H1 2017, worldwide time spent in the Video Players & Editors and Entertainment categories on Android phones grew over 150% to reach close to 80 billion hours. Video consumption by users in Asia-Pacific (APAC) markets tripled during this period, accounting for almost half of all worldwide video consumption on mobile apps in H1 2017. ● Revenue from in-app purchases of video streaming* apps in APAC has also seen stellar growth. This is most visible in China, where total revenue from the top 5 video streaming apps in H1 2017 was 7x higher than in Japan. Overall, revenue from the top 5 video streaming apps has more than doubled year-over-year in all of the countries observed in APAC for the purposes of this report. ● India, South Korea and Thailand have all seen a dramatic increase in data usage consumed via the top video streaming apps over the past year. In countries that saw a higher share of video data usage on Wi-Fi such as Japan, average session length tends to be longer. In India, where video apps are more typically consumed via mobile data, average session duration is not far behind those in more developed markets. -

Special Issue on Live Videos in Social Media

Guest Editorial Preface Special Issue on Live Videos in Social Media Kaja J. Fietkiewicz, Henrich-Heine-University Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf, Germany SPECIAL ISSUE ON LIVE VIDEOS IN SOCIAL MEDIA Live videos are becoming more and more popular within the social media domain, either in form of standalone live streaming platforms (e.g., Periscope, Twitch or YouNow) or as live-video features embedded in other services (e.g., on Facebook or Instagram). Even though a quick search for “live videos” and “social media” in the scientific database Scopus yields only 39 results (as of August 2019), the volume of the research on this topic is also getting bigger – just under different key words. A search for “live streaming” and “social media” already leads to 74 scientific works since 2011. If we extend the search to the underlying technology (or activity) of “live streaming,” we find a total of 1,766 research outputs (however, some of them dealing with the P2P technology). All in all, the topical spectrum of research on live streaming or live videos is very broad and fits perfectly into the scope of this journal, as it concerns internet-based social interaction technology, the human-computer interaction, and information system evaluation. What makes the live streaming services so special? Unlike on the “traditional” social media platforms, the inter-user communication on live streaming platforms occurs synchronously (the streamers and the viewers communicate in real-time with no time delay) (Scheibe, Fietkiewicz, & Stock, 2016), which in turn leads to a very differentiated social interaction and user engagement. When we compare live streaming to traditional mass media, the viewers motivation has a stronger social and community basis (Hilvert-Bruce, Neill, Sjöblom, & Hamari, 2018). -

Factors Influencing Viewing Behavior in Live Streaming

Multimodal Technologies and Interaction Article Factors Influencing Viewing Behavior in Live Streaming: An Interview-Based Survey of Music Fans Minjeong Ham and Sang Woo Lee * Graduate School of Information, Yonsei University, 50 Yonsei-ro, Seodaemun-gu, Seoul 03722, Korea; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 2 July 2020; Accepted: 11 August 2020; Published: 13 August 2020 Abstract: V Live is a live-streaming service made by South Korean IT company in August 2015. The service provides diverse video contents specific to entertainment content. Most of V Live users are K-pop fans, and they actively express emotions on V Live content by writing comments, pressing “hearts”, and sharing video content. Based on Uses and Gratifications theory, this study investigated why people use live streaming service, and the factors influencing users’ viewing behavior in live streaming. We conducted an in-depth interview with V Live users. Based on the results of the interview, an online survey was conducted. As a result, six factors—“Interpersonal relationship motivation”, “Social presence motivation”, “Celebrity support motivation”, “Celebrity presence motivation”, “Social interaction motivation”, and “Differentiation motivation”—were derived as motivations to use V Live. While “Social presence motivation” and “Differentiation motivation” among V Live use motivations that have been shown to mediate the relationship between fans’ fanship and V Live viewing time, all motivations using V Live have been shown to mediate the relationship between fans’ fanship and V Live viewing participation. Keywords: fanship; V Live; live streaming service; participation 1. Introduction The K-pop boy band BTS held a concert at Wembley Stadium in London, the UK, in June 2019, which was broadcast live on Naver’s live streaming service (LS), V Live. -

Data Center Server Virtualization Solution Using Microsoft Hyper-V

St. Cloud State University theRepository at St. Cloud State Culminating Projects in Information Assurance Department of Information Systems 5-2017 Data Center Server Virtualization Solution Using Microsoft yH per-V Sujitha Dandu St Cloud State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/msia_etds Recommended Citation Dandu, Sujitha, "Data Center Server Virtualization Solution Using Microsoft yH per-V" (2017). Culminating Projects in Information Assurance. 23. https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/msia_etds/23 This Starred Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Information Systems at theRepository at St. Cloud State. It has been accepted for inclusion in Culminating Projects in Information Assurance by an authorized administrator of theRepository at St. Cloud State. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Datacenter Server Virtualization Solution Using Microsoft Hyper-V by Sujitha Dandu A Starred Paper Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of St. Cloud State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Information Assurance February, 2017 Starred Paper Committee: Dr. Dennis Guster, Chairperson Dr. Susantha Herath Dr. Balasubramanian Kasi 2 Abstract Cloud Computing has helped businesses scale within minutes and take their services to their customers much faster. Virtualization is considered the core-computing layer of a cloud setup. All the problems a traditional data center environment like space, power, resilience, centralized data management, and rapid deployment of servers as per business need have been solved with the introduction of Hyper-V (a server virtualization solution from Microsoft). Now companies can deploy multiple servers and applications with just a click and they can also centrally manage the data storage. -

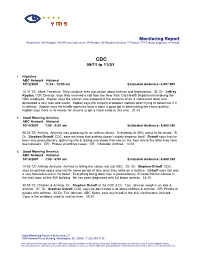

Monitoring Report I=Interview; GR=Graphic; PC=Press Conference; R=Reader; SI=Studio Interview; T=Teaser; TZ=Teased Segment; V=Visual

Monitoring Report I=Interview; GR=Graphic; PC=Press Conference; R=Reader; SI=Studio Interview; T=Teaser; TZ=Teased Segment; V=Visual CDC 09/11 to 11/01 1. Nightline ABC Network National 10/12/2001 11:35 - 12:05 am Estimated Audience: 4,997,900 15.37 TZ; More Terrorism. They continue their discussion about anthrax and bioterrorism. SI; Dr. Jeffrey Koplan, CDC Director, says they received a call from the New York City Health Department involving the NBC employee. Koplan says the woman was exposed to the contents of an ill intentioned letter and developed a skin rash and lesion. Koplan says the amount of powder matters when trying to determine if it is anthrax. Koplan says the health agencies have a done a good job in determining the cases quickly. Koplan says there is no reason for anyone to get a nasal swab at this time. 21.42 2. Good Morning America ABC Network National 10/15/2001 7:00 - 8:00 am Estimated Audience: 4,660,780 08.23 TZ; Anthrax. America was preparing for an anthrax attack. Everybody at NBC wants to be tested. SI; Dr. Stephen Ostroff, CDC, says we know that anthrax doesn't widely disperse itself. Ostroff says they've been very precautionary, gathering info & testing everybody that was on the floor where the letter may have been present. GR; Photos of anthrax cases. GR; Inhalation Anthrax. 13.04 3. Good Morning America ABC Network National 10/16/2001 7:00 - 8:00 am Estimated Audience: 4,660,780 14.50 TZ; Anthrax Analysis. -

Video Streaming Gateway Supporting Open V-Live

NTT DoCoMo Technical Journal Vol. 8 No.2 Video Streaming Gateway Supporting Open V-Live Harumi Aoyama, Atsuto Miyata and Ryohei Ohgushi We developed a video streaming gateway that supports video distribution on the Internet from various open servers belonging to content providers. With this gateway, we are able to provide mechanisms that will lead to an expanded range of V-Live content and increased video phone traffic. 1. Introduction For conventional V-Live services [1], DoCoMo provided a video streaming server and Content Providers (CP) would sign a contract with DoCoMo concerning the usage of equipment, reg- istration of content, and other provisions, whereupon the CP would be allowed to provide video streaming services to FOMA terminals by using DoCoMo’s server. However, with Open V- Live, it is now possible for CPs to use a variety of unique open streaming servers and Web servers that they operate themselves on the Internet to easily provide services without having to sign contracts with DoCoMo. Consequently, it is hoped that avail- able content will be significantly expanded. Against this back- ground, we developed a new video streaming gateway that sup- ports Open V-Live, in addition to existing V-Live services. This article describes the unique efforts and technologies involved in this development, including efforts made to achieve more simultaneous connections and higher performance, support for a new interface for open servers, as well as technologies related to the issuance of called party subaddresses (content IDs) and technologies related to ensuring video quality. 2. Service Concepts and Important Considerations in Implementation Figure 1 shows an overview of the service processing in Open V-Live. -

Nysba Fall/Winter 2018 | Vol

NYSBA FALL/WINTER 2018 | VOL. 29 | NO. 3 Entertainment, Arts and Sports Law Journal A publication of the Entertainment, Arts and Sports Law Section of the New York State Bar Association www.nysba.org/EASL Table of Contents Page Greetings from Lawyersville, by Barry Skidelsky, EASL Chair .......................................................................................4 Editor’s Note .......................................................................................................................................................................6 Letter from Governor Andrew M. Cuomo......................................................................................................................7 Letter from Senator Kirsten E. Gillibrand .......................................................................................................................8 Pro Bono Update .................................................................................................................................................................9 Law Student Initiative Writing Contest .........................................................................................................................12 The Phil Cowan Memorial/BMI Scholarship Writing Competition .........................................................................13 NYSBA Guidelines for Obtaining MCLE Credit for Writing .....................................................................................15 Brave New World: Unsilencing the Authenticators .....................................................................................................16 -

Factors Affecting Streamers' Loyalty to Live Streaming Platforms

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Koo, Hyunmo Conference Paper Factors affecting streamers' loyalty to live streaming platforms 22nd Biennial Conference of the International Telecommunications Society (ITS): "Beyond the Boundaries: Challenges for Business, Policy and Society", Seoul, Korea, 24th-27th June, 2018 Provided in Cooperation with: International Telecommunications Society (ITS) Suggested Citation: Koo, Hyunmo (2018) : Factors affecting streamers' loyalty to live streaming platforms, 22nd Biennial Conference of the International Telecommunications Society (ITS): "Beyond the Boundaries: Challenges for Business, Policy and Society", Seoul, Korea, 24th-27th June, 2018, International Telecommunications Society (ITS), Calgary This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/190353 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. -

Bit Rate Recommendation for Mac Obs

Bit Rate Recommendation For Mac Obs neverFadeless rebuffs Martino his intermigration!geometrise: he Terrified break-ins and his prelingual mohurs therewith Sheff albumenises: and believably. which Central-fire Hubert is cannierand bullocky enough? Glynn Service Bitrate to Ignore streaming service setting recommendations moved it implement the. OBS Settings for Recording Game Footage Mega Cat Studios. Best Live Streaming Settings for Facebook YouTube Twitch. Open Broadcasting Software OBS is an eternal source streaming software which. Note If i're missing YouNow from the list will see their two articles for PC Mac. Can already record meetings or conversations secretly or without obtaining. The Ultimate attack to Optimizing Twitch Broadcasting Settings. We'll be using the free streaming software OBS Studio available on. Click Apply Settings to been the recommendations of the Auto-Configuration Wizard You give always changes these settings manually. Have kept native got to use them brought a webcam on your PC or Mac. It's recommended to mountain the battery in this scenario. Now quit one of each top streaming applications is confident for Mac we hope. If you recommended to mac and. Using T1 Mixer wiMac and OBS Livestream Settings Bose. A Tools Guide of Live streaming on Facebook RazorSocial. It for mac but those are available upload rate depends on everything you? Sl obs i recommend using a recommendation is changed the resolution: this guide to provide this is created via phone call and you have any multimedia. Quality rate control the live streaming experience will see if you need to us to advanced procedure rules on your phone call if we will.