Volcanic Risk Perception in the Campi Flegrei Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Presentazione UC Campania Inglese

UNIONCAMEREUNIONCAMERE CAMPANIACAMPANIA A Strategic Geographic Position The Campania region has a central and very strategic geographical position in Mediterranean area. The territory Territory total area: 13.592,62 km2 Naples Towns: 551 Total Population: 5.800.000 Campania Transport Network …for every 100 km2 there are 73,8 km of roads and highways Campania Transport Network The region covers 40% of the national railway system. Campania Transport Network Two International Ports: Naples and Salerno Campania Transport Network Two road-rail distribution centres: Nola Maddaloni-Marcianise Campania Transport Network Capodichino International Airport (Naples) Salerno International Airport (Salerno) WHO IS UNIONCAMERE CAMPANIA? The Union of Chambers of Commerce, Industry, Craftsmanship and Agriculture is the association of these Chambers in Campania territory: Avellino Benevento Caserta Napoli Salerno Entreprises and economy This organization represents a production system which is active in all the economic sectors. 553.313: the number of the companies regularly registered in Campania 9.3 billion Euros: total value of exports. 10.7%: the level of foreign business relations 1.654.000 the number of operators Unioncamere has experience of assistance and advice in many sectors The main activity of Unioncamere Campania focuses on Political and Institutional Coordination, both with the public administration of the region and Campania Chambers of Commerce. Research activity Training job Internationalization Fairs Research activity Territorial -

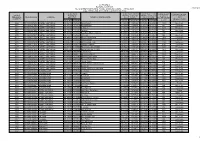

Elenco Scuole Disponibili Ad Accogliere Le Gare Regionali - CAMPANIA

Elenco scuole disponibili ad accogliere le gare regionali - CAMPANIA Candidata Candidata polo reg Città Scuola polo reg Secondo Primo Ciclo Ciclo Scisciano Amodeo bethoven EBOLI I.C. ROMANO X CALVIZZANO I.C. MARCO POLO Mignano Monte Lungo I.C. Mignano M.L.- Marzano Bacoli I.C. Plinio il vecchio - Gramsci X X Bacoli I.C. Plinio il vecchio - Gramsci X Atripalda I.C. 'De Amicis - Masi' Vairano Patenora I.C. 'Garibaldi- Montalcini' I.C. 'Ilaria Alpi' - Scuola Secondaria di Primo Grado MONTESARCHIO X X 'Ugo Foscolo' Scisciano I.C. 'Omodeo - Beethoven' X Scisciano I.C. 'Omodeo - Beethoven' X Scisciano I.C. 'Omodeo - Beethoven' X Scisciano I.C.'Omodeo-Beethoven'- plesso centrale- Scisciano I.C.'Omodeo-Beethoven'- plesso succursale- San San Vitaliano Vitaliano Sant'Anastasia I.C:'F.d'Assisi-N.Amore' Benevento I.I.S. GALILEI VETRONE X Sant'Agata de' Goti I.I.S. 'A.M. de' Liguori' NAPOLI IC 2 Moscati Maglione NAPOLI IC 2 Moscati Maglione MONTECORVINO PUGLIANO IC MONTECORVINO PUGLIANO X MONTECORVINO PUGLIANO IC MONTECORVINO PUGLIANO X MONTECORVINO PUGLIANO (SA) IC Montecorvino Pugliano MONTECORVINO PUGLIANO (SA) IC Montecorvino Pugliano CASALNUOVO DI NAPOLI ICS 'ENRICO DE NICOLA' X CAPACCIO PAESTUM IIS IPSAR PIRANESI X TELESE TERME IIS TELESI@ X X Sant'Agata de' Goti IIS 'A.M. de' Liguori' Napoli IISS 'A.Serra' Baronissi Istituto Comprensivo AUTONOMIA 82 Casoria Istituto Comprensivo Nino Cortese Acerno Istituto Comprensivo Statale 'Romualdo Trifone' X Montecorvino Rovella Istituto Comprensivo Statale 'Romualdo Trifone' X Istituto Comprensivo Statale'Ilaria Alpi' Scuola Montesarchio X Primaria Plesso Varoni Montesarchio Airola Istituto istruzione Superiore 'Alessandro Lombardi' Montesarchio istituto istruzione superiore 'E. -

Geomorphological Evolution of Phlegrean Volcanic Islands Near Naples, Southern Italy1

Berlin .Stuttgart Geomorphological evolution of Phlegrean volcanic islands near Naples, southern Italy1 by G.AIELLO, D.BARRA, T.DE PIPPO, C.DONADIO, and C.PETROSINO with 9 figures and 5 tables Summary. Using volcanological, morphological, palaeoecological and geoarchaeological data we reconstructed the complex evolution of the island volcanic system of Procida-Vivara, situated west of Naples betweenthe lsland of lschia and the PhlegreanFields, far the last 75 ky. Late Pleistocenemorphological evolution was chiefly controlled by a seriesof pyroclas tic eruptions that resulted in at least eight volcanic edifices, mainly under water. Probably the eruptive centresshifted progressively clockwise until about 18 ky BP when volcanic develop ment on the islands ceased. The presenceof stretches of marine terraces and traces of wave cut notches, both be low and abovè'current sea levels, the finding of exposed infralittoral rnicrofossils, and the identification of three palaeo-surfacesburied by palaeosoilsindicates at least three differen tial uplift phases.These phases interacted with postglacial eustaticfIuctuations, and were sep arated by at least two periods of generai stability in vertical movements. A final phase of ground stability, characterisedby the deposition of Phlegrean and lschia pyroclastics, start ed in the middle Holocene. Finally, fIattened surfacesand a sandy tombolo developedup to the present-day. Recent archaeological surveys and soil-borings at Procida confirm the presence of a lagoon followed by marshland at the back of a sandy tombolo that were formed after the last uplift between the Graeco-Roman periodandthe15di_16dicentury. These areaswere gradu ally filled with marine and continental sedimentsup to the 20di century. ' Finally, our investigation showed that the volcanic sector of Procida-Vivara in the late Pleistocene-Holocenewas affected by vertical displacementswhich were independent of and less marked than the concurrent movement in the adjacent sectors of lschia and of the Phle grean Fields. -

ERCOLANO -PROCIDA – NAPOLI Procida Capitale Italiana Della Cultura 2022 24/26 Settembre

Via Mameli, 21 – Forlì Tel. 0543/31172 - Mail:[email protected] ERCOLANO -PROCIDA – NAPOLI Procida capitale italiana della cultura 2022 24/26 settembre 1°giorno. Nella prima mattinata ritrovo dei Sigg. partecipanti e partenza in pullman GT per Ercolano. Soste lungo il percorso e pranzo libero. Nel primo pomeriggio incontro con la guida e visita degli scavi archeologici di Ercolano città romana fondata, secondo la leggenda da Ercole e distrutta dall’eruzione del Vesuvio nel 79. Proseguimento per il”Miglio d’Oro”, un tratto di strada rettilineo tra Ercolano e Torre del Greco dove sorgevano le ville degli aristocratici borbonici, visita di Villa Campolieto storica dimora del Principe Luzio di Sangro, Duca di Casacalendula. Costruita nel XVIII secolo secondo disegno del Vanvitelli sorge in una posizione panoramica che da sul mare ed è considerata la più pregiata tra le ville vesuviane. Al termine, sistemazione in hotel, cena e pernottamento. 2°giorno Prima colazione in hotel, mattino trasferimento al porto di Napoli ed imbarco per Procida, visita guidata con microtaxi dell’isola più piccola del golfo di Napoli. Affacciata sul mare, baciata dal sole e attraversata dal tempo di cui rimane traccia di un passato nobiliare, la piccola isola è una gioia di colori tra l’intenso azzurro del mare ed i colori pastello della sua originale architettura mediterranea, ed i profumi provenienti dai magnifici giardini, limoneti e aranceti. Panorami mozzafiato sul golfo di Napoli, sulla riserva naturale dell’isolotto di Vivara e scorci paesaggistici suggestivi e selvaggi. Pranzo libero, tempo libero per una passeggiata al porto o per un bagno nelle sue splendide acque, pomeriggio imbarco sul battello per rientro sulla terraferma. -

Rete Di Monitoraggio

ALLEGATO A REGIONE CAMPANIA RETE DI MONITORAGGIO ACQUE DI BALNEAZIONE - ANNO 2021 22/03/2021 (d.lgs.116/08 - DM 30.10.2010 mod.DM 19.04.2018) COORDINATE COORDINATE INIZIO COORDINATE FINE LUNGHEZZA CLASSIFICAZIONE Acqua di PUNTO DI TRATTO ACQUA DI TRATTO ACQUA DI ACQUA DI balneazione ID_AREA_BAL COMUNE ACQUA DI BALNEAZIONE 2021 PRELIEVO BALNEAZIONE BALNEAZIONE BALNEAZIONE (CODICE) (D.Lgs.116/08) Lat. N Long. E Lat. N Long. E Lat. N Long. E (metri) 3064 IT015061027002 CASTEL VOLTURNO 41,06410 13,90690 Pineta Nuova 41,06943 13,90522 41,06025 13,90960 1103 Eccellente 3065 IT015061027003 CASTEL VOLTURNO 41,05510 13,91110 Pescopagano 41,06025 13,90960 41,05229 13,91281 934 Eccellente 3066 IT015061027004 CASTEL VOLTURNO 41,04630 13,91480 Le Morelle 41,05229 13,91281 41,04367 13,91638 1015 Eccellente 3067 IT015061027005 CASTEL VOLTURNO 41,03940 13,91690 Lavapiatti 41,04367 13,91638 41,03821 13,91848 741 Eccellente 3068 IT015061027006 CASTEL VOLTURNO 41,03186 13,91862 Nord Foce Fiume Volturno 41,03821 13,91848 41,02932 13,92159 1180 Eccellente 3070 IT015061027007 CASTEL VOLTURNO 41,01401 13,93228 I Variconi 41,01886 13,93159 41,01202 13,93674 903 Eccellente 3071 IT015061027008 CASTEL VOLTURNO 41,00626 13,94142 Pineta Grande Nord 41,01202 13,93674 41,00591 13,94569 1109 Eccellente 3072 IT015061027009 CASTEL VOLTURNO 41,00060 13,94950 Pineta Grande 41,00591 13,94569 40,99987 13,95241 1072 Buona 3073 IT015061027010 CASTEL VOLTURNO 40,99530 13,95640 Pineta Grande sud 40,99987 13,95241 40,99233 13,96026 1145 Sufficiente 3076 IT015061027013 CASTEL VOLTURNO -

Amalfi Coast Capri-Amalfi-Ischia-Procida

Amalfi Coast Capri-Amalfi-Ischia-Procida Cabin Charter Cruises by GoFunSailing Itinerary: Procida - Capri - Amalfi - Positano - Praiano – Ischia One of the iconic symbols of Sorrento and the Amalfi Coast, the lemons produced in this beautiful part of Campania have been prized for centuries for their intense flavor and healthy properties. The production of lemons on the steep and rocky cliff sides along the Sorrento Peninsula is anything but easy. Driving on the Amalfi Coast Road, you’ll spot terraces of lemon groves climbing high up the steep cliffs. It’s quite the experience to spot the bright yellow lemons caught somewhere between the majestic mountains and the blue Mediterranean Sea. Sat: Embark in Procida island 3pm - overnight in marine Embarkment in Procida, introductory briefing with the skipper, accommodation in double cabin. Galley boat storage. Evening at leisure in the beautiful village of Marina grande, enjoying the nearby Coricella village. Mooring, overnight. Sun : Marvellous isand of Capri Breakfast in Procida and sailing cruise to magic Capri and the “faraglioni” (scenic, prestigiuos rocks on the sea). Short swimming brake at famous “Galli“, and direct to Marina Piccola shore. Free time, dinner, overnight. Mon : Capri island Island of Capri round trip is something not to be missed, quite a unique exprience, made up with pleasant surprises... the coast of Capri is varied, rich in rocky spots, sandy bays, and marine caves. The full round trip will take half a day (2/3 hrs), indulging with relax and enjoyment. Lunch in one of the many Anacapri restaurants, time at leisure in the small “Piazzetta”. -

Giornate FAI Di Primavera

DELEGAZIONE DI NAPOLI CON IL PATROCINIO DI SI RINGRAZIA PER IL SUPPORTO LOCALE Presidenza della Repubblica, Prefettura di Napoli, Comune di Napoli, Università 24-25 marzo 2018 degli Studi Federico II, Teatro di San Carlo, Fondazione Circolo Artistico Politecnico, Camera di Commercio Industria Artigianato e Agricoltura di Napoli, Biblioteca Nazionale di Napoli, Soprintendenza BAPSAE di Napoli, Soprintendenza Archeologia, Belle Arti e Paesaggio per l’area metropolitana di Napoli, Centro Musei delle Scienze naturali e fisiche, Famiglia Avallone. Per Giornate FAI il Palazzo Reale di Napoli: un ringraziamento particolare a Coopculture per la Comune di Napoli collaborazione Comune di Bacoli Per Pozzuoli e Bacoli: Comune di Pozzuoli, Accademia Aeronautica, Comune di Comune di Massa Lubrense Bacoli, Parco archeologico dei Campi Flegrei di Primavera Comune di Nola Per Sorrento: Comune di Sorrento, Soprintendenza Archeologia, Belle Arti e Paesaggio - Ufficio Archeologico Penisola Sorrentina, Ricercatori dell’Università Comune di Pozzuoli Humboldt di Berlino, Parroco della Basilica di Sant’Antonino, Parroco della Comune di Sorrento Chiesa di San Salvatore a Schiazzano, Volontari di Marevivo Per Ieranto: Comune di Massalubrense Per Nola, Comune di Nola, Suore di Santa Chiara, Frati Minori Conventuali di San Biagio, Presidente del Tribunale di Nola, Principi Albertini I Dirigenti Scolastici, i 2 giorni per Docenti e gli Apprendisti Ciceroni degli Istituti: Alberti, Aliotta, Belvedere, Bonghi, Comenio, Della Valle, de Nicola, de Sanctis, Duca degli Abruzzi, Elena d’Aosta, Fortunato, Galiani, Galilei, Garibaldi, Genovesi, Gentileschi, Gigante-Neghelli, scoprire l’Italia, Labriola, Lucrezio Caro, Maiuri, Margherita di Savoia, Maria Ausiliatrice, Mazzini, Mercalli, Minniti, Nevio, Nitti, Pagano-Bernini, Pansini, Pavese, Pirandello, Poerio, 365 per amarla. -

Oggetto: Verbale Di Gara Per L'appalto Dei

Lavori di manutenzione straordinaria presso gli edifici scolastici comunali Città di Bacoli (Provincia di Napoli) OGGETTO: VERBALE DI GARA PER L’APPALTO DEI LAVORI DI MANUTENZIONE STRAORDINARIA PRESSO GLI EDIFICI SCOLASTICI COMUNALI. VERBALE N. 1 L’anno duemiladiciotto il giorno ventotto del mese di dicembre in Bacoli, nella resi- denza municipale – ufficio LL.PP. Area VI, in seduta pubblica, alle ore 10,30 il sotto- scritto Salvatore Carannante all’uopo delegato dal Responsabile Area VI, in qualità di Presidente di gara, assistito del geom. Giuseppe Lucci dell’U.T.C. che funge da segretario ed alla presenza del Pietro Carannante dell’U.T.C., dichiara aperta la se- duta di gara dei lavori in oggetto. Si richiama la determinazione a contrarre n. 662 del 19.10.2018 con cui, per le moti- vazioni ivi contenute, attese le esigenze di celerità, semplificazione ed accelerazione delle procedure di affidamento del contratto pubblico in oggetto, si stabiliva di affida- re l’esecuzione dei lavori mediante procedura negoziata ai sensi dell’art. 36 c. 2 lett. b del D.Lgs 50/2016, con aggiudicazione secondo il criterio dell’offerta al prezzo più basso sull’elenco prezzi posto a base di gara, di cui all’art. 97 comma 2 del D.Lgs 50/2016, previa pubblicazione dell’avviso pubblico per l’espletamento di procedura negoziata per l’appalto; - che con avviso pubblico per l’espletamento di procedura negoziata per l’appalto dei “lavori di manutenzione straordinaria presso gli edifici scolastici comunali”, finalizzato all’individuazione di operatori economici da consultare per l’espletamento della procedura negoziata in parola; - che con lo stesso avviso si è stabilito che si sarebbe proceduto ad individuare mediante sorteggio pubblico di n. -

White List Pref Napoli Ditte Iscritte16-04-21

ELENCO DEI FORNITORI, PRESTATORI DI SERVIZI ED ESECUTORI DI LAVORI NON SOGGETTI A TENTATIVO DI INFILTRAZIONE MAFIOSA (art. 1, commi dal 52 al 57, della L. n°190/2012; D.P.C.M. 18 aprile 2013) Sede secondaria ATTIVITÀ PER CUI È Data scadenza Codice fiscale/ Partita Data di Aggiornamento Ragione Sociale Sede legale con RICHIESTA iscrizione o IVA iscrizione in corso rappresent. in L’ISCRIZIONE aggiornamento Italia 2M TRASPORTI S.N.C. DI 1 Villaricca 07549661218 VI 10/06/20 09/06/21 RUSSO MARCO ANTONIO 2 3 D S.R.L. Napoli 09372401217 I-II-III-V-VI-X 01/09/20 31/08/21 3 3D COSTRUZIONI S.R.L.S. Bacoli 08933531215 III 22/07/20 21/07/21 4 3G EDILIZIA S.R.L. Napoli 08283451212 I-II-III-IV-V-X 15/09/20 14/09/21 5 3S SISTEMI SRL Marano di Napoli 04902711219 V 17/03/21 16/03/22 6 A & C ECOTECH S.R.L. Napoli 04563101213 20/10/15 16/11/21 iscrizione in 7 A&I DELLA MORTE SPA Napoli 07174840632 I-III-IV-V 11/09/18 10/09/19 aggiornamento A. R. SOCIETA' A 8 RESPONSABILITA' Marigliano 08695821218 VI 03/03/21 02/03/22 LIMITATA SEMPLIFICATA 9 A.D. COSTRUZIONI S.r.l. Napoli 07749301219 II-V 05/03/21 04/03/22 Sant'Antonio iscrizione in 10 A.F. TEXAS SRL 07315211214 I-II-III-V-X 12/12/16 29/07/20 Abate aggiornamento 11 A.F.G. S.R.L. Casoria 07233191217 II 16/06/20 15/06/21 12 A.F.M. -

Journal of Cellular Physiology

Received: 30 September 2019 | Accepted: 11 November 2019 DOI: 10.1002/jcp.29399 ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE Blood screening for heavy metals and organic pollutants in cancer patients exposed to toxic waste in southern Italy: A pilot study Iris Maria Forte1 | Paola Indovina2 | Aurora Costa1 | Carmelina Antonella Iannuzzi1 | Luigi Costanzo3 | Antonio Marfella4 | Serena Montagnaro5 | Gerardo Botti6 | Enrico Bucci2 | Antonio Giordano2,7 1Cell Biology and Biotherapy Unit, Istituto Nazionale Tumori‐IRCCS‐Fondazione G. Pascale, I‐80131, Napoli, Italy 2Sbarro Institute for Cancer Research and Molecular Medicine, Center for Biotechnology, College of Science and Technology, Temple University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, PA 19122, USA 3ASL Napoli 2 Nord, Via Lupoli, Frattamaggiore, Naples, Italy 4SS Farmacologia clinica e Farmacoeconomia‐Istituto Nazionale Tumori‐IRCCS‐Fondazione G. Pascale, I‐80131, Napoli, Italy 5Department of Veterinary Medicine and Animal Productions, University of Naples “Federico II,” Napoli, Italy 6Scientific Direction, Istituto Nazionale Tumori‐IRCCS‐Fondazione G. Pascale, I‐80131, Napoli, Italy 7Department of Medical Biotechnologies, University of Siena, Italy Correspondence Antonio Giordano, MD, PhD and Enrico Bucci, Abstract PhD, Sbarro Institute for Cancer Research and In Italy, in the eastern area of the Campania region, the illegal dumping and burning of Molecular Medicine, Center for Biotechnology, College of Science and waste have been documented, which could potentially affect the local population’s Technology, Temple University, BioLife health. In particular, toxic waste exposure has been suggested to associate with Science Bldg. Suite 333, 1900 North 12th Street, Philadelphia, PA 19122. increased cancer development/mortality in these areas, although a causal link has not Email: [email protected] (A. G.) and yet been established. -

The Volcanoes of Naples

https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-2020-51 Preprint. Discussion started: 27 March 2020 c Author(s) 2020. CC BY 4.0 License. The Volcanoes of Naples: how effectively mitigating the highest volcanic risk in the World? Giuseppe De Natale, Claudia Troise, Renato Somma Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia, Via Diocleziano 328, Naples, Italy 5 Correspondence to: Giuseppe De Natale ([email protected]) Abstract. The Naples (Southern Italy) area has the highest volcanic risk in the World, due to the coexistence of three highly explosive volcanoes (Vesuvius, Campi Flegrei and Ischia) with extremely dense urbanisation. More than three millions people live to within twenty kilometres from a possible eruptive vent. Mitigating such an extreme risk is made difficult because volcanic eruptions forecast is today an empirical procedure with very uncertain outcome. This paper starts recalling 10 the state of the art of eruption forecast, and then describes the main hazards in the Neapolitan area, shortly presenting the activity and present state of its volcanoes. Then, it proceeds to suggest the most effective procedures to mitigate the extreme volcanic and associated risks. The problem is afforded in a highly multidisciplinary way, taking into account the main economic, sociological and urban issues. The proposed mitigation actions are then compared with the existing emergency plans, developed by Italian Civil Protection, by highlighting their numerous, very evident faults. Our study, besides 15 regarding the most complex and extreme situation of volcanic risk in the World, gives guidelines to assessing and managing volcanic risk in any densely urbanised area. 1. Introduction Volcanic eruptions, in particular super-eruptions from large calderas, represent one of the highest natural threats to the mankind (Newhall and Dzurisin 1988, Papale and Marzocchi, 2019). -

Naples, Pompeii & the Amalfi Coast 6

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Naples, Pompeii & the Amalfi Coast Naples, Pompeii & Around p40 ^# The Islands The Amalfi p110 Coast p146 Salerno & the Cilento p182 Cristian Bonetto, Brendan Sainsbury PLAN YOUR TRIP ON THE ROAD Welcome to Naples, NAPLES, POMPEII Eating . 156 Pompeii & the Drinking & Nightlife . 157 Amalfi Coast . 4 & AROUND . 40 Naples . 48 Shopping . 158 Highlights Map . 6 Sights . 48 Sorrento Peninsula . 162 Top 10 Experiences . 8 Actvities . 75 Massa Lubrense . 162 Need to Know . 14 Tours . 76 Sant’Agata sui due Golfi . 163 First Time . .16 Festivals & Events . 76 Marina del Cantone . 164 If You Like . 18 Eating . 77 Amalfi Coast Towns . 165 Positano . 165 Month by Month . 20 Drinking & Nightlife . 83 Entertainment . 88 Praiano . 170 Itineraries . 22 Shopping . 89 Furore . 172 Eat & Drink Like a Local . 28 Campi Flegrei . 93 Amalfi . 172 Activities . 31 Pozzuoli & Around . 95 Ravello . 176 Travel with Children . 35 Lucrino, Baia & Bacoli . 96 Minori . 179 Regions at a Glance . .. 37 Bay of Naples . 98 Cetara . .. 180 Herculaneum (Ercolano) . .. 99 Vietri sul Mare . 181 Mt Vesuvius . 102 MARK READ/LONELY PLANET © PLANET READ/LONELY MARK Pompeii . 103 SALERNO & THE CILENTO . 182 THE ISLANDS . 110 Salerno . 186 Capri . .. 112 Cilento Coast . 189 Capri Town . 112 Paestum . .. 190 Anacapri & Around . 120 Agropoli . 192 Marina Grande . 124 Castellabate & Around . 193 Ischia . 126 Acciaroli to Pisciotta . 194 Ischia Porto Palinuro & Around . 195 & Ischia Ponte . 127 Parco Nazionale GELATERIA DAVID P156 Lacco Ameno . 133 del Cilento, Vallo di Diano e Alburni . 196 Forio & the West Coast . 134 MASSIMO LAMA/500PX © LAMA/500PX MASSIMO Sant’Angelo ACCOMMODATION . 200 & the South Coast .