Desolation and Doctrine in Thére`Se of Lisieux

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dialogue Between Religion and Science in Today's World from The

International Journal of Orthodox Theology 8:3 (2017) 203 urn:nbn:de:0276-2017-3075 Gavril Trifa The Dialogue between Religion and Science in Today’s World from the View of Orthodox Spirituality Abstract One of the core issues of today’s world, the dialogue between science and religion has recently come to the attention of new fields of knowledge, which points to a change in some of the “classical” elements. Having a different history in the East and the West, in Catholic and Orthodox Christianity, the relation between faith and science has lived through some problematic centuries, marked by the attempt of some scientific domains to prove the universe’s materialist ontology and thus the uselessness of religion. This paper aims to present an overview of the Rev. Assist. Prof. Ph.D. stages that marked the often radical Gavril Trifa, Faculty of separation of science from religion, by Orthodox Theology of the highlighting the mutations recorded West University of Timi- during the past few decades not only şoara, Romania 204 Gavril Trifa in society but also in the lives of the young, as a result of the unprecedented development of technology. With technology failing to raise both communication and interpersonal communication to the anticipated level, recent research does not hesitate in emphasizing the unfavourable consequences bring about by the development of the means of communication, regarding the human being’s relation to oneself and one’s neighbours. The solutions we have identified enable an update of the patristic model concerning the relation between religion and science, in the spirit of humility, the one that can bring the Light of life. -

Mary in the Doctrine of Berulle on the Mysteries of Christ Vincent R

Marian Studies Volume 36 Proceedings of the Thirty-Sixth National Convention of The Mariological Society of America Article 11 held in Dayton, Ohio 1985 Mary in the Doctrine of Berulle on the Mysteries of Christ Vincent R. Vasey Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/marian_studies Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Vasey, Vincent R. (1985) "Mary in the Doctrine of Berulle on the Mysteries of Christ," Marian Studies: Vol. 36, Article 11. Available at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/marian_studies/vol36/iss1/11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Marian Library Publications at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marian Studies by an authorized editor of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Vasey: Mary in the Doctrine of Berulle MARY IN THE DOCTRINE OF BERULLE ON THE MYSTERIES OF CHRIST Two monuments Berulle left the Church, aere perennina: more enduring than bronze, are his writings and his Congrega tion of the Oratory. He took part in the great controversies of his time, religious and political, but his figure takes its greatest lus ter with the passing of years because of his spiritual work and the influence he exerts in the Church by those endued with his teaching. From his integrated life originated both his works and his institution; that is why both his writings and the Oratory are intimately connected. His writings in their final synthesis-and we are concerned above all with the culmination of his contem plation and study-center about Christ, and his restoration of the priesthood centers about Christ. -

1A2ae.10.2.Responsio 2

THE TRINITARIAN GIFT UNFOLDED: SACRIFICE, RESURRECTION, COMMUNION JOHN MARK AINSLEY GRIFFITHS, BSC., MSC., MA Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy July 2015 Abstract Contentious unresolved philosophical and anthropological questions beset contemporary gift theories. What is the gift? Does it expect, or even preclude, some counter-gift? Should the gift ever be anticipated, celebrated or remembered? Can giver, gift and recipient appear concurrently? Must the gift involve some tangible ‘thing’, or is the best gift objectless? Is actual gift-giving so tainted that the pure gift vaporises into nothing more than a remote ontology, causing unbridgeable separation between the gift-as-practised and the gift-as-it-ought-to- be? In short, is the gift even possible? Such issues pervade scholarly treatments across a wide intellectual landscape, often generating fertile inter-disciplinary crossovers whilst remaining philosophically aporetic. Arguing largely against philosophers Jacques Derrida and Jean-Luc Marion and partially against the empirical gift observations of anthropologist Marcel Mauss, I contend in this thesis that only a theological – specifically trinitarian – reading liberates the gift from the stubborn impasses which non-theological approaches impose. That much has been argued eloquently by theologians already, most eminently John Milbank, yet largely with a philosophical slant. I develop the field by demonstrating that the Scriptures, in dialogue with the wider Christian dogmatic tradition, enrich discussions of the gift, showing how creation, which emerges ex nihilo in Christ, finds its completion in him as creatures observe and receive his own perfect, communicable gift alignment. In the ‘gift-object’ of human flesh, believers rejoicingly discern Christ receiving-in-order-to-give and giving-in- order-to-receive, the very reciprocal giftedness that Adamic humanity spurned. -

Hearing the Call of God: Toward a Theological Phenomenology of Vocation

HEARING THE CALL OF GOD: TOWARD A THEOLOGICAL PHENOMENOLOGY OF VOCATION Submitted by Meredith Ann Secomb B.A. (Hons) B.Theol. M.A. (Psych) Theol.M. A thesis submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy National School of Theology Faculty of Theology and Philosophy Australian Catholic University Research Services Locked Bag 4115 Fitzroy Victoria 3065 Australia March 2010 ii Statement of Sources This thesis contains no material published elsewhere or extracted in whole or in part from a thesis by which I have qualified for or been awarded another degree or diploma. No parts of this thesis have been submitted towards the award of any other degree or diploma in any other tertiary institution. No other person’s work has been used without due acknowledgement in the main text of the thesis. Signed: _____________________ Date: _____________________ iii Abstract This study contributes to the development of a theological phenomenology of vocation. In so doing, it posits that the distressing condition of existential unrest can be a foundational motivation for the vocational search and argues that the discovery of one’s vocation, which necessarily entails an engagement with existential mystery, is served by attentiveness to what is termed the “pneumo-somatic” data of embodied consciousness. Hence, the study does not canvass the broad range of phenomena that would contribute to a comprehensive phenomenology of vocation. Rather, it seeks to highlight an aspect frequently overlooked in the vocational search, namely the value of attentiveness to one’s experience of the body in the context of prayerful engagement with the mystery of God. -

Reading Records of Literary Authors: a Comoatisom.Of Some Publishedfaotebocks

DOCUMENT INSURE j ED41.820. CS 204 003 0 AUTHOR Murray, Robin Mark '. TITLE. Reading Records of Literary Authors: A ComOatisom.of Some Publishedfaotebocks. PUB DATE Dec 77 NOTE 118p.; N.A. thesis, The Ilniversity.of Chicago . I EDRS PRICE f'"' NF-S0.83 HC-$6.01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Authors; Bibliographies;_ Rooks; ,ocompcsiticia (Literary); *Creative Writing; *Diariei; Literature* Masters Theses; *Poets; Reading Habits; Reading Materials; *Recrtational Reading; Study Habits IDENTIFIERS Notebooks;.*Note Taking - ABSTRACT The significance ofauthore reading notes may lie not only in their mechanical function as inforna'tion storage devices providing raw materials for writing, but also in their ability to 'concentrate and to mobilize the latent ,emotional and. creative 1 resources of their keepers. This docmlent examines records of 'reading found in the published notebcols'of eight najcr_British.and United States writers of the sixteenth through twentieth. centuries. Through eonparison of their note-taking practices, the following topics are explored: how each author came to make reading notes, the,form.in which notes were' made, and the vriteiso habits of consulting; and using their notes (with special reference to distinctly literary uses). The eight writers whose notebooks ares-exaninea in dtpth are Francis Badonc John Milton, Samuel Coleridge,.Ralph V. Emerson, Henry D. Thoreau, Mark Twain, Thomas 8ardy, and Thomas Violfe.:The trends that emerge from these eight case studiesare discussed, and an extensive bibliograity of published -

Hans Urs Von Balthasar Society

Reports of Developing or Ad Hoc Groups 273 HANS URS VON BALTHASAR SOCIETY EDWARD OAKES' PATTERN OF REDEMPTION Presenter: Edward T. Oakes Respondent: Mark A. Mcintosh Most theologians agree that their discipline is a "second-order" activity, meaning a subsequent, reasoned reflection upon the prior data of faith and revelation. Oakes introduced his book by showing how Balthasar himself handles this distinction between first- and second-order activity internal to Christian faith. As it happens, Balthasar's own degree was in Germanistik and not theology, and so it is not surprising to learn that he draws on literary categories to explain the role of theology in relation to the life of faith. In the first volume of the Theodramatik, Balthasar devotes a number of pages to a contrast between epic, lyric and dramatic modes of thought, heavily favoring the latter. The priority he gives to the dramatic mode is his way of emphasizing the first-order claims of faith: faith is first and foremost a doing, a response to a kerygma which demands obedience before it gives birth to thought. And this response is the drama of the soul saying "Yes" or "No" to God. This is why Balthasar holds that the art of drama, especially when we are speaking in poetic terms, is the highest form of art, because it encompasses all other art forms. Nonetheless, Oakes took a few moments to explore the contrast between epic and lyric styles. In the history of poetry one can notice two distinct trends that run through the course of literature: that between the civic and the private. -

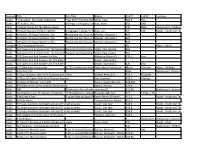

Resource Typeitle Sub-Title Author Call #1 Call #2 Location Books

Resource TitleType Sub-Title Author Call #1 Call #2 Location Books "Impossible" Marriages Redeemed They Didn't End the StoryMiller, in the MiddleLeila 265.5 MIL Books "R" Father, The 14 Ways To Respond To TheHart, Lord's Mark Prayer 242 HAR DVDs 10 Bible Stories for the Whole Family JUV Bible Audiovisual - Children's Books 10 Good Reasons To Be A Catholic A Teenager's Guide To TheAuer, Church Jim. Y/T 239 Books - Youth and Teen Books 10 Habits Of Happy Mothers, The Reclaiming Our Passion, Purpose,Meeker, AndMargaret Sanity J. 649 Books 10 Habits Of Happy Mothers, The Reclaiming Our Passion, Purpose,Meeker, AndMargaret Sanity J. 649 Books 10 Habits Of Happy Mothers, The Reclaiming Our Passion, Purpose,Meeker, AndMargaret Sanity J. 649 Compact Discs100 Inspirational Hymns CD Music - Adult Books 101 Questions & Answers On The SacramentsPenance Of Healing And Anointing OfKeller, The Sick Paul Jerome 265 Books 101 Questions & Answers On The SacramentsPenance Of Healing And Anointing OfKeller, The Sick Paul Jerome 265 Books 101 Questions And Answers On Paul Witherup, Ronald D. 235.2 Paul Compact Discs101 Questions And Answers On The Bible Brown, Raymond E. Books 101 Questions And Answers On The Bible Brown, Raymond E. 220 BRO Compact Discs120 Bible Sing-Along songs & 120 Activities for Kids! Twin Sisters Productions Music Children Music - Children DVDs 13th Day, The DVD Audiovisual - Movies Books 15 days of prayer with Saint Elizabeth Ann Seton McNeil, Betty Ann 235.2 Elizabeth Books 15 Days Of Prayer With Saint Thomas Aquinas Vrai, Suzanne. -

The Cathars of Languedoc As Heretics

PROJECT DEMONSTRATING EXCELLENCE The Cathars of Languedoc as Heretics: From the Perspectives of Five Contemporary Scholars by Anne Bradford Townsend Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy with a concentration in Arts And Sciences and a specialization in Medieval Religious Studies July 9, 2007 Core Faculty Advisor: Robert McAndrews, Ph.D. Union Institute & University Cincinnati, Ohio UMI Number: 3311971 Copyright 2008 by Townsend, Anne Bradford All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ® UMI UMI Microform 3311971 Copyright 2008 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 E. Eisenhower Parkway PO Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 ABSTRACT The purpose of this dissertation is to demonstrate that the Cathar community of Languedoc, far from being heretics as is generally thought, practiced an early form of Christianity. A few scholars have suggested this interpretation of the Cathar beliefs, but none have pursued it critically. In this paper I use two approaches. First, this study will examine the arguments of five contemporary English language scholars who have dominated the field of Cathar research in both Britain and the United States over the last thirty years, and their views have greatly influenced the study of the Cathars. -

ABSTRACT Evelyn Waugh and La Nouvelle Théologie Dan Reid

ABSTRACT Evelyn Waugh and La Nouvelle Théologie Dan Reid Makowsky, Ph.D. Mentor: Ralph C. Wood, Ph.D. This dissertation seeks to provide a more profound study of Evelyn Waugh’s relation to twentieth-century Catholic theology than has yet been attempted. In doing so, it offers a radical revision of our understanding of Waugh’s relation to the Second Vatican Coucil. Waugh’s famous contempt for the liturgical reforms of the early 1960s, his self-described “intellectual” conversion, and his identification with the Council of Trent, have all contributed to a commonplace perception of Waugh as a reactionary Catholic stridently opposed to reform. However, careful attention to Waugh’s dynamic artistic concerns and the deeply sacramental theology implicit in his later fiction reveals a striking resemblance to the most important Catholic theological reform movement of the mid-twentieth century: la nouvelle théologie. By comparing Waugh’s artistic project to the theology of the Nouvelle theologians, who advocated the recovery of a fundamentally sacramental theology, this dissertation demonstrates that the two mirror one another in many of their basic concerns. This mirroring was no mere coincidence. Waugh’s long-time mentor Father Martin D’Arcy was steeped in many of the same sacramentally-minded thinkers as the Nouvelle theologians. Through D’Arcy’s theological influence as well as the deepening of Waugh’s own faith, he, too, developed a sacramental cast of mind. In reading some of the key works of Waugh’s later years, I will show how Waugh realized this sacramental outlook in his art. Ultimately, this dissertation argues that Waugh’s main contribution to the renewal of sacramental thought within Catholicism lies in his portrayal of personal vocation as the remedy for acedia, or sloth, which he considered the “besetting sin” of the age. -

Twentieth-Century French Philosophy Twentieth-Century French Philosophy

Twentieth-Century French Philosophy Twentieth-Century French Philosophy Key Themes and Thinkers Alan D. Schrift ß 2006 by Alan D. Schrift blackwell publishing 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK 550 Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia The right of Alan D. Schrift to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. First published 2006 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd 1 2006 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Schrift, Alan D., 1955– Twentieth-Century French philosophy: key themes and thinkers / Alan D. Schrift. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-1-4051-3217-6 (hardcover: alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1-4051-3217-5 (hardcover: alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-1-4051-3218-3 (pbk.: alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1-4051-3218-3 (pbk.: alk. paper) 1. Philosophy, French–20th century. I. Title. B2421.S365 2005 194–dc22 2005004141 A catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library. Set in 11/13pt Ehrhardt by SPI Publisher Services, Pondicherry, India Printed and bound in India by Gopsons Papers Ltd The publisher’s policy is to use permanent paper from mills that operate a sustainable forestry policy, and which has been manufactured from pulp processed using acid-free and elementary chlorine-free practices. -

An Analysis of Alfred Loisy's Un Mythe Apologetique

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1980 Misunderstood Mystic: An Analysis of Alfred Loisy's Un Mythe Apologetique Patricia Prendergast Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Prendergast, Patricia, "Misunderstood Mystic: An Analysis of Alfred Loisy's Un Mythe Apologetique" (1980). Master's Theses. 3116. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/3116 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1980 Patricia Prendergast MISUNDERSTOOD MYSTIC: AN ANALYSIS OF ALFRED LOISY'S UN MYTHE APOLOGETIQUE by Patricia Prendergast A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Loyola University of Chicago in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts May 1980 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I should like to take this opportunity to thank Dr. Jon Nilson for his support and encouragement during the writing of this thesis. It was in one of his classes that I first encountered Loisy and through our conversations that the possibility of doing this thesis was manifested. In addition to his helpful suggestions I am exceedingly grateful for his academic integrity which, while concerned to resolve our differences through discussion, never al lowed him to displace my approach with his. -

Anglican Studies (ANGL) 1

Anglican Studies (ANGL) 1 Anglican Studies (ANGL) ANGL 537 C.S. Lewis: Author, Apologist, and Anglican (3) This course will examine selected writings of C. S. Lewis (1898-1963) with special attention to the historical development and Anglican character of his work. It will consider how Lewis treated certain key themes through more than one genre, focusing particularly on his apologetics, science fiction, and fantasy. Themes and texts considered will include suffering and eschatology (The Problem of Pain / The Great Divorce), natural law and posthumanism (The Abolition of Man / That Hideous Strength), theism and naturalism (Miracles / The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe), and human and divine love (The Four Loves / Till We Have Faces). ANGL 539 The Anglican Tradition of Reason: Butler, Newman, and Farrer (3) This course will examine the theological and philosophical aspects of an important tradition spanning three centuries of English Anglicanism. Focusing on the writings of three definitive figures who drew upon and shaped this tradition, we will examine Joseph Butler in the eighteenth century, John Henry Newman in the nineteenth century, and Austin Farrer in the twentieth century. All three were noted preachers and scholars, as well as original thinkers and devout churchmen; the works we read will represent these different modes and concerns of their writing. We will also examine the historical context in both church and society during their respective periods, and consider the significance and implications of this ’tradition of reason’ for Anglican theology today. This course also has the attributes of CHHT and THEO. ANGL 540 The Shape of the Communion (3) This is a course on the Instruments of Communion and how they have shaped Global Anglicanism.