Edom at the Crossroads of “Incense Routes” in the 8Th–7Th Centuries B.C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Galilee, Galileans I. Geography

907 Galilee, Galileans 908 potential for anti-Sacramentarian polemic (Comm. Galilee (mAr 9 : 2). Not only do we have here a divi- Gen. 31.48-55). sion between Upper and Lower Galilee, but the mention of the sycamore tree (Shiqma) reflects the Bibliography : ■ Calvin, J., Commentaries on the First Book of Moses Called Genesis, vol. 2 (trans. J. King; Grand Rapids, differences in altitude and vegetation between Up- Mich. 1989). ■ Luther, M., Luther’s Works, vol. 6 (ed. J. J. per Galilee (1200 m. above sea level) and Lower Gal- Pelikan, Saint Louis, Miss. 1970). ■ Sheridan, M. (ed.), Gen- ilee (600 m. above sea level), as sycamores do not esis 12–50 (Ancient Christian Commentary on Scripture, vol. grow in areas higher than 400 m. above sea level. 2; Downers Grove, Ill., 2002). ■ Skinner, J., A Critical and The term “Galileans” appears only in the late Exegetical Commentary on Genesis (ICC; Edinburgh 1930). Second Temple period. This is a good reason to con- ■ Speiser, E. A., Genesis (AB 1; New York/London 1964). nect it to the self-identification of the Jews living in John Lewis this region or the Judeans identifying the Galileans. See also /Mizpah, Mizpeh To understand this self-identity it is necessary to present the development of the Jewish settlement in the Galilee from the First Temple period to the Galilee, Galileans 1st century CE. It is very clear today, according to I. Geography many archaeological excavations which were con- II. Hebrew Bible/Old Testament ducted in the Galilee that its Israelite population III. New Testament collapsed after the Assyrian attack in 732 BCE. -

2 Chronicles 25-28 Good Evening Church, I Am Glad You Could Make It out Tonight

Page 1 of 29 2 Chronicles 25-28 Good evening church, I am glad you could make it out tonight. Hello to those of you watching online. Tonight we are going to continue in our study through the Old Testament, we will be in 2 Chronicles Chapter 25 and we will attempt to get through Chapter 28 tonight. We have much going on in our world, and for me, it is a joy to gather here with you all to come under God’s Word. This place is the only place that makes sense, and His Word is the only True Comfort in this World. So let’s pray, and we will get into our text tonight. Well, we finished last time by looking at the assassination of King Joash of Judah, and we will pick up right after his death… Look now at chapter 25… Amaziah Reigns in Judah(2 Kings 14:1-6) 25:1 Amaziah was twenty-five years old when he became king, and he reigned twenty-nine years in Jerusalem. His mother's name was Jehoaddan of Jerusalem. 2 And he did what was right in the sight of the Lord, but not with a loyal heart. Now Amaziah was a reformer just like Joash his father. Page 2 of 29 But we see here at the end of verse two, he fell short of complete reform. He did not live up to the standard that King David had set as the template, and he continued to allow the high places to exist as we saw in 2 Kings Chapter 14. -

Three Conquests of Canaan

ÅA Wars in the Middle East are almost an every day part of Eero Junkkaala:of Three Canaan Conquests our lives, and undeniably the history of war in this area is very long indeed. This study examines three such wars, all of which were directed against the Land of Canaan. Two campaigns were conducted by Egyptian Pharaohs and one by the Israelites. The question considered being Eero Junkkaala whether or not these wars really took place. This study gives one methodological viewpoint to answer this ques- tion. The author studies the archaeology of all the geo- Three Conquests of Canaan graphical sites mentioned in the lists of Thutmosis III and A Comparative Study of Two Egyptian Military Campaigns and Shishak and compares them with the cities mentioned in Joshua 10-12 in the Light of Recent Archaeological Evidence the Conquest stories in the Book of Joshua. Altogether 116 sites were studied, and the com- parison between the texts and the archaeological results offered a possibility of establishing whether the cities mentioned, in the sources in question, were inhabited, and, furthermore, might have been destroyed during the time of the Pharaohs and the biblical settlement pe- riod. Despite the nature of the two written sources being so very different it was possible to make a comparative study. This study gives a fresh view on the fierce discus- sion concerning the emergence of the Israelites. It also challenges both Egyptological and biblical studies to use the written texts and the archaeological material togeth- er so that they are not so separated from each other, as is often the case. -

THROUGH the BIBLE ISAIAH 15-19 in the Bible God Judges Individuals, and Families, and Churches, and Cities, and Even Nations…

THROUGH THE BIBLE ISAIAH 15-19 ! In the Bible God judges individuals, and families, and churches, and cities, and even nations… I would assume He also judges businesses, and labor unions, and school systems, and civic groups, and athletic associations - all of life is God’s domain. Starting in Isaiah 13, God launches a series of judgments against the Gentile nations of his day. Making Isaiah’s list are Babylon, Assyria, Philistia, Moab, Ethiopia, Egypt, Edom, Tyre, and Syria. Tonight we’ll study God’s burden against the nations. ! Isaiah 15 begins, “The burden against Moab…” Three nations bordered Israel to the east - Moab, Edom, and Ammon. Today this area makes up the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan - a pro-Western monarchy with its capitol city of Amman - or Ammon. ! Today, it’s fashionable to research your roots - track down the family tree. Websites like Ancestry.com utilize the power of the Internet to uncover your genealogy. For some folks this is a fun and meaningful pastime. For me, I’ve always been a little leery… I suspect I’m from a long line of horse thieves and swindlers. I’m not sure I want to know my ancestry. This is probably how most Moabites felt regarding their progenitors… ! The Moabites were a people with some definite skeletons in the closest! Their family tree had root rot. Recently, I read of a Michigan woman who gave her baby up for adoption. Sixteen years later she tracked him down on FB… only to get romantically involved. She had sex with her son… Obviously this gal is one sick pup. -

PSALMS 60 and 61

PSALMS 60 and 61 Old Testament history confirms the truth that when God has been rejected by his people-- the nation of Israel--he delivers them into the hands of her enemies. In this 60st psalm, Israel is suffering persecution from the Arameans. This psalm commemorates one memorable part of that battle, when Joab returns and kills 12,000 Edomites in the Valley of Salt. David praises God for the triumph, recognizing that the help of man is vain. Psalm 60 For the choir director; according to Shushan Eduth. A Mikhtam of David, to teach; when he struggled with Aram-naharaim and with Aram-zobah, and Joab returned, and smote twelve thousand of Edom in the Valley of Salt. 1 O God, You have rejected us. You have broken us; You have been angry; O, restore us. 2 You have made the land quake, You have split it open; heal its breaches, for it totters. 3 You have made Your people experience hardship; You have given us wine to drink that makes us stagger. 4 You have given a banner to those who fear You, that it may be displayed because of the truth. Selah 5 That Your beloved may be delivered, save with Your right hand, and answer us! 6 God has spoken in His holiness: “I will exult, I will portion out Shechem and measure out the valley of Succoth. 7 “Gilead is Mine, and Manasseh is Mine; Ephraim also is the helmet of My head; Judah is My scepter. 8 “Moab is My washbowl; over Edom I shall throw My shoe; shout loud, O Philistia, because of Me!” 9 Who will bring me into the besieged city? Who will lead me to Edom? 10 Have not You Yourself, O God, rejected us? And will You not go forth with our armies, O God? 11 O give us help against the adversary, for deliverance by man is in vain. -

Revolutionaries in the First Century

BYU Studies Quarterly Volume 36 Issue 3 Article 9 7-1-1996 Revolutionaries in the First Century Kent P. Jackson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq Part of the Mormon Studies Commons, and the Religious Education Commons Recommended Citation Jackson, Kent P. (1996) "Revolutionaries in the First Century," BYU Studies Quarterly: Vol. 36 : Iss. 3 , Article 9. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol36/iss3/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Studies Quarterly by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Jackson: Revolutionaries in the First Century masada and life in first centuryjudea Published by BYU ScholarsArchive, 1996 1 BYU Studies Quarterly, Vol. 36, Iss. 3 [1996], Art. 9 revolutionaries in the first century kent P jackson zealotszealousZealots terrorists freedom fighters bandits revolutionaries who were those people whose zeal for religion for power or for freedom motivated them to take on the roman empire the great- est force in the ancient world and believe that they could win because the books ofofflaviusjosephusflavius josephus are the only source for most of our understanding of the participants in the first jewish revolt we are necessarily dependent on josephus for the answers to this question 1 his writings will be our guide as we examine the groups and individuals involved in the jewish rebellion I21 in -

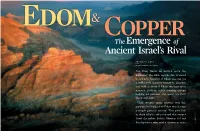

EDOM and COPPER Photo by Mohammad Najjar Mohammad by Photo Photo by Thomas E

Edom& Copper The Emergence of Ancient Israel’s Rival Thomas E. L E v y a n d m ohammad Najjar Did King David do battle with the Edomites? The Bible says he did. It would be unlikely, however, if Edom was not yet a sufficiently complex society to organize and field an army, if Edom was just some nomadic Bedouin tribes roaming around looking for pastures and water for their sheep and goats. Until recently, many scholars took this position: In David’s time Edom was at most a simple pastoral society.1 This gave fuel to those scholars who insisted that ancient DUBY TAL / Israel (or rather, Judah) likewise did not ALBATROSS develop into a state until a century or more 24 BI B LICA L ARCHAEOLOGY REVIEW • JULY/AUGUST 2006 JULY/AUGUST 2006 • BI B LICA L ARCHAEOLOGY REVIEW 25 EDOM AND COPPER PHOTO BY MOHAMMAD NAJJAR PHOTO BY THOMAS E. LEVY after David’s time. Ancient Israel, they argued, explore the role of early mining and metallurgy on r PILES OF RUBBLE (opposite) bestride the outline of a large e v was just like the situation east of the Jordan—no i square fortress and more than 100 smaller buildings at social evolution from the beginnings of agriculture R AMMON n complex societies in Ammon, Moab or Edom. a Khirbat en-Nahas in the Edomite lowlands of Jordan. The and sedentary village life from the Pre-pottery d r According to this school of thought, David was o Neolithic period (c. 8500 B.C.E.) to the Iron Age J massive black mounds are slag, a waste product of the Jerusalem not really a king, but a chieftain of a few simple SEA copper-smelting process, indicating that large-scale copper (1200–500 B.C.E.) in Jordan. -

Israel's Conquest of Canaan: Presidential Address at the Annual Meeting, Dec

Israel's Conquest of Canaan: Presidential Address at the Annual Meeting, Dec. 27, 1912 Author(s): Lewis Bayles Paton Reviewed work(s): Source: Journal of Biblical Literature, Vol. 32, No. 1 (Apr., 1913), pp. 1-53 Published by: The Society of Biblical Literature Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3259319 . Accessed: 09/04/2012 16:53 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Society of Biblical Literature is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Biblical Literature. http://www.jstor.org JOURNAL OF BIBLICAL LITERATURE Volume XXXII Part I 1913 Israel's Conquest of Canaan Presidential Address at the Annual Meeting, Dec. 27, 1912 LEWIS BAYLES PATON HARTFORD THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY problem of Old Testament history is more fundamental NO than that of the manner in which the conquest of Canaan was effected by the Hebrew tribes. If they came unitedly, there is a possibility that they were united in the desert and in Egypt. If their invasions were separated by wide intervals of time, there is no probability that they were united in their earlier history. Our estimate of the Patriarchal and the Mosaic traditions is thus conditioned upon the answer that we give to this question. -

The Second Book of Samuel

A PATRISTIC COMMENTARY THE SECOND BOOK OF SAMUEL FR. TADROS Y. MALATY 2004 Initial edition Translated by: DR. GEORGE BOTROS Revised by SAMEH SHAFIK Coptic Orthodox Christian Center 491 N. Hewes St. Orange, California 92869-2914 INTRODUCTION As this book in the Hebrew origin, is a complementary to the first book of Samuel, we urge the reader to refer back to the introduction of that book. According to the Jewish tradition, the authors of this book were the prophets Nathan and Gad, beside some of those who were raised in the school of the prophets, founded by the prophet Samuel. In the Septuagint version, it is called “The second Kingdoms book.” WHEN WAS IT WRITTEN? It was written after the division of the kingdom, and before the captivity. It embraces a complete record of the reign of King David (2 Samuel 5: 5); and mentions the kings of ‘Judah,’ as distinct from those of ‘Israel’ (1 Samuel 27: 6). ITS FEATURES 1- Its topic was a survey of King David’s life, following his strife with king Saul, who was killed by the enemies at the end of the previous book; a narration of king David’s ascension to the throne, his wars, and the moving up of the Tabernacle of God to Jerusalem. It also gave a record of David’s fall in certain sins, with all the incessant troubles and grieves they entailed. In other words, this book represents the history of the people during the 40 years of king David’s reign. Its study is considered to be of special importance to everyone intending to comprehend David’s psalms. -

The Legal Status of Tiran and Sanafir Islands Rajab, 1438 - April 2017

22 Dirasat The Legal Status of Tiran and Sanafir Islands Rajab, 1438 - April 2017 Askar H. Enazy The Legal Status of Tiran and Sanafir Islands Askar H. Enazy 4 Dirasat No. 22 Rajab, 1438 - April 2017 © King Faisal Center for Research and Islamic Studies, 2017 King Fahd National Library Cataloging-In-Publication Data Enazy, Askar H. The Legal Status of Tiran and Sanafir Island. / Askar H. Enazy, - Riyadh, 2017 76 p ; 16.5 x 23 cm ISBN: 978-603-8206-26-3 1 - Islands - Saudi Arabia - History 2- Tiran, Strait of - Inter- national status I - Title 341.44 dc 1438/8202 L.D. no. 1438/8202 ISBN: 978-603-8206-26-3 Table of Content Introduction 7 Legal History of the Tiran-Sanafir Islands Dispute 11 1928 Tiran-Sanafir Incident 14 The 1950 Saudi-Egyptian Accord on Egyptian Occupation of Tiran and Sanafir 17 The 1954 Egyptian Claim to Tiran and Sanafir Islands 24 Aftermath of the 1956 Suez Crisis: Egyptian Abandonment of the Claim to the Islands and Saudi Assertion of Its Sovereignty over Them 26 March–April 1957: Saudi Press Statement and Diplomatic Note Reasserting Saudi Sovereignty over Tiran and Sanafir 29 The April 1957 Memorandum on Saudi Arabia’s “Legal and Historical Rights in the Straits of Tiran and the Gulf of Aqaba” 30 The June 1967 War and Israeli Reoccupation of Tiran and Sanafir Islands 33 The Status of Tiran and Sanafir Islands in the Egyptian-Israeli Peace Treaty of 1979 39 The 1988–1990 Egyptian-Saudi Exchange of Letters, the 1990 Egyptian Decree 27 Establishing the Egyptian Territorial Sea, and 2016 Statements by the Egyptian President -

The Revised Version of the Old Testament

THE REVISED VERSION 01!1 THE OLD TESTAMENT. 57 It was because I saw the living Christ, and " heard the words of His mouth," and, I beseech you, listen to no words which make His dominion less sovereign, and His sole and all sufficient work on the cross less mighty as the only power that knits earth to heaven. So the sum of this whole matter is-abide in Christ. Let us root and ground our lives and characters in Hirn, and then God's inmost desire will be gratified in regard to us, and He will bring even us stainless and blameless into the blaze of His presence. There we shall all have to stand, and let that all penetrating light search us through and through. How do we expect to be then " found of Him in peace, without spot and blameless " ? There is but one way-to Jive in constant exercise of faith in Christ, and grip Him so close and sure that the world, the flesh and the devil cannot make us loosen our fingers. Then He will hold us up, and His great purpose, which brought Him to earth, and nailed Him to the cross, will be fulfilled in us, and at last, we shalJ lift up voices of wondering praise " to Him who is able to keep us from falling, and to present us faultless before the presence of His glory with exceeding joy." ALEXANDER MACLAREN. THE REVISED VERSION OF THE OLD TESTA MENT. A ORITIG.AL ESTIMATE. FIRST PAPER. A NOTED judicial dictum lately vested the censorship of lite rature and art in the general British public. -

7/7/19 the Reign of Uzziah 2Chron. 26:1-23 There Are Some Leader That

1 2 7/7/19 2. The industrious spirit, “He built Elath and restored it to Judah, after the king rested The Reign of Uzziah with his fathers.” vs. 2 2Chron. 26:1-23 3. The age and length of reign of Uzziah, “Uzziah was sixteen years old when he There are some leader that stand out in history for became king, and he reigned fifty-two years their excellence, then there are others though they in Jerusalem.” vs. 3 a-b were excellent made a foolish decision or other and a. He is the second longest reigning king of that is all they are remembered for, this is Uzziah. Judah 52 years. * Like Ex-President Richard Nixon, he is remembered b. Manaaseh is first 55 years. 2Chron. 33:1- for Watergate. 20 4. The mother of Uzziah, “His mother’s name So the reign of Uzziah as it is revealed from three was Jecholiah of Jerusalem.” vs. 3c perspectives according to God. 2Chron. 26:1-23 * Jecholiah “Y@kolyah”, means “Yahweh I. The reign of Uzziah over Judah. vs. 1-5 is able”, what a wonderful name. II. The rule of Uzziah for Judah. vs. 6-15 III. The wrongdoing of Uzziah. vs. 16-23 B. The godly character of Uzziah. vs. 4-5 1. The godly conduct of Uzziah, “And he did I. The reign of Uzziah over Judah. vs. 1-5 what was right in the sight of the LORD, * The parallel passages. 2Kings 14:21-22; 15:1-7 according to all that his father Amaziah had done.” vs.