In Defense of Augmented Intervals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Generalized Interval System and Its Applications

Generalized Interval System and Its Applications Minseon Song May 17, 2014 Abstract Transformational theory is a modern branch of music theory developed by David Lewin. This theory focuses on the transformation of musical objects rather than the objects them- selves to find meaningful patterns in both tonal and atonal music. A generalized interval system is an integral part of transformational theory. It takes the concept of an interval, most commonly used with pitches, and through the application of group theory, generalizes beyond pitches. In this paper we examine generalized interval systems, beginning with the definition, then exploring the ways they can be transformed, and finally explaining com- monly used musical transformation techniques with ideas from group theory. We then apply the the tools given to both tonal and atonal music. A basic understanding of group theory and post tonal music theory will be useful in fully understanding this paper. Contents 1 Introduction 2 2 A Crash Course in Music Theory 2 3 Introduction to the Generalized Interval System 8 4 Transforming GISs 11 5 Developmental Techniques in GIS 13 5.1 Transpositions . 14 5.2 Interval Preserving Functions . 16 5.3 Inversion Functions . 18 5.4 Interval Reversing Functions . 23 6 Rhythmic GIS 24 7 Application of GIS 28 7.1 Analysis of Atonal Music . 28 7.1.1 Luigi Dallapiccola: Quaderno Musicale di Annalibera, No. 3 . 29 7.1.2 Karlheinz Stockhausen: Kreuzspiel, Part 1 . 34 7.2 Analysis of Tonal Music: Der Spiegel Duet . 38 8 Conclusion 41 A Just Intonation 44 1 1 Introduction David Lewin(1933 - 2003) is an American music theorist. -

8.1.4 Intervals in the Equal Temperament The

8.1 Tonal systems 8-13 8.1.4 Intervals in the equal temperament The interval (inter vallum = space in between) is the distance of two notes; expressed numerically by the relation (ratio) of the frequencies of the corresponding tones. The names of the intervals are derived from the place numbers within the scale – for the C-major-scale, this implies: C = prime, D = second, E = third, F = fourth, G = fifth, A = sixth, B = seventh, C' = octave. Between the 3rd and 4th notes, and between the 7th and 8th notes, we find a half- step, all other notes are a whole-step apart each. In the equal-temperament tuning, a whole- step consists of two equal-size half-step (HS). All intervals can be represented by multiples of a HS: Distance between notes (intervals) in the diatonic scale, represented by half-steps: C-C = 0, C-D = 2, C-E = 4, C-F = 5, C-G = 7, C-A = 9, C-B = 11, C-C' = 12. Intervals are not just definable as HS-multiples in their relation to the root note C of the C- scale, but also between all notes: e.g. D-E = 2 HS, G-H = 4 HS, F-A = 4 HS. By the subdivision of the whole-step into two half-steps, new notes are obtained; they are designated by the chromatic sign relative to their neighbors: C# = C-augmented-by-one-HS, and (in the equal-temperament tuning) identical to the Db = D-diminished-by-one-HS. Corresponding: D# = Eb, F# = Gb, G# = Ab, A# = Bb. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfihn master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 3 0 0 North Z eeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 9401386 Enharmonicism in theory and practice in 18 th-century music Telesco, Paula Jean, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1993 Copyright ©1993 by Telesco, Paula Jean. -

Diatonic Harmony

Music Theory for Musicians and Normal People Diatonic Harmony tobyrush.com music theory for musicians and normal people by toby w. rush although a chord is technically any combination of notes Triads played simultaneously, in music theory we usually define chords as the combination of three or more notes. secundal tertial quartal quintal harmony harmony harmony harmony and œ harmony? œœ œ œ œ œœ œ œ tertial œ œ œ septal chords built from chords built from chords built from chords built from seconds form thirds (MORE perfect fourths perfect fifths tone clusters, SPECifically, from create a different can be respelled as respectively. harmony, which are not major thirds and sound, used in quartal chords, harmonic so much minor thirds) compositions from and as such they harmony? as timbral. form the basis of the early 1900s do not create a most harmony in and onward. separate system of are the same as as with quintal harmony, these harmony, as with quintal the common harmony. secundal practice period. sextal well, diminished thirds sound is the chord still tertial just like major seconds, and if it is built from diminished augmented thirds sound just thirds or augmented thirds? like perfect fourths, so... no. œ œ the lowest note in the chord & œ let’s get started when the chord is in simple on tertial harmony form is called œ the the & œ with the smallest root. fifth œ chord possible: names of the œ third ? œ when we stack the triad. other notes œ the chord in are based on root thirds within one octave, their interval we get what is called the above the root. -

(Semitones and Tones). We Call These “Seconds. A

Music 11, 7/10/06 Scales/Intervals We already know half steps and whole steps (semitones and tones). We call these “seconds.” Adjacent pitch names are always called seconds, but because the space between adjacent pitch names can vary, there are different types of second: Major second (M2) = whole step = whole tone Minor second (m2) = half step = semitone In a major scale, all the seconds are major seconds (M2) except 2: E-F and B-C are minor seconds (m2). Inversion Suppose we take the two notes that make up a second, and “flip” them over—that is, lets put the lower note up an octave, so that it lies above the other note. The distance between E-D is now D-E. We say that the “inversion” of E-D is D-E, and the interval that results is not a second, but instead a seventh. More specifically, the inversion of a major second (M2) is a minor seventh (m7). There are two things to remember about inversions: 1. When an interval is inverted, their numbers add-up to 9. M2 and m7 are inversions of each other, and we can see that 2 + 7 = 9. 2. When a major interval is inverted, its quality becomes minor, and vise versa. The inversion of a M2 is a m7. Major has become minor. Likewise, the inversion of a minor second (m2) is a major seventh (M7). By these rules, we can invert other intervals, like thirds. Study the following chart: # of semitones interval name inversion # of semitones 1 m2 M7 (11) 2 M2 m7 (10) 3 m3 M6 (9) 4 M3 m6 (8) Obviously, wider intervals have more semitones between pitches. -

The Consecutive-Semitone Constraint on Scalar Structure: a Link Between Impressionism and Jazz1

The Consecutive-Semitone Constraint on Scalar Structure: A Link Between Impressionism and Jazz1 Dmitri Tymoczko The diatonic scale, considered as a subset of the twelve chromatic pitch classes, possesses some remarkable mathematical properties. It is, for example, a "deep scale," containing each of the six diatonic intervals a unique number of times; it represents a "maximally even" division of the octave into seven nearly-equal parts; it is capable of participating in a "maximally smooth" cycle of transpositions that differ only by the shift of a single pitch by a single semitone; and it has "Myhill's property," in the sense that every distinct two-note diatonic interval (e.g., a third) comes in exactly two distinct chromatic varieties (e.g., major and minor). Many theorists have used these properties to describe and even explain the role of the diatonic scale in traditional tonal music.2 Tonal music, however, is not exclusively diatonic, and the two nondiatonic minor scales possess none of the properties mentioned above. Thus, to the extent that we emphasize the mathematical uniqueness of the diatonic scale, we must downplay the musical significance of the other scales, for example by treating the melodic and harmonic minor scales merely as modifications of the natural minor. The difficulty is compounded when we consider the music of the late-nineteenth and twentieth centuries, in which composers expanded their musical vocabularies to include new scales (for instance, the whole-tone and the octatonic) which again shared few of the diatonic scale's interesting characteristics. This suggests that many of the features *I would like to thank David Lewin, John Thow, and Robert Wason for their assistance in preparing this article. -

The Melodic Minor Scale in Selected Works of Johann

THE MELODIC MINOR SCALE IN SELECTED WORKS OF JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH by SHARON LOUISE TOWNDROW, B. M. A THESIS IN MUSIC THEORY Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC Approved Accepted December, 1977 I ^-f* ^ c.^r ^ ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to express my sincere appreciation to my thesis committee, Dr. Judson Maynard, Dr. Mary Jeanne van Appledorn, and Dr. Richard McGowan. I am especially indebted to Dr. Maynard, chairman of my com mittee, whose suggestions and assistance proved most valuable during the preparation of this study. I also gratefully acknowledge the cour tesies rendered by the staff of the Texas Tech University Library. 11 i"&e'' CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 I. TONIC HARMONY 3 II. HARMONIES OF THE FIRST CLASSIFICATION 13 III. HARMONIES OF THE SECOND CLASSIFICATION 24 IV. MISCELLANEOUS HARMONIC FUNCTIONS 34 CONCLUSION 45 NOTES 47 BIBLIOGRAPHY 48 111 LIST OF EXAMPLES TONIC HARMONY Sixth and Seventh Scale Degrees as Nonharmonic Tones Ex. I-l. Fugue No. 20, P. 179., m. 25 3 Ex. 1-2. Ricercare a 6 voci, p. 17., mm. 78-79 4 Ex. 1-3. Prelude No. 4, p. 105., m. 39 5 Ex. 1-4. Concerto No. 1 for Clavier, p. 38., mm. 5-6 6 Ex. 1-5. Cantata No. 106, p. 15., mm. 3-5 6 Ex. 1-6. Suite No. 3, p. 37., mm. 17-18 7 Ex. 1-7. Suite No. 3, p. 40., m. 24 • 7 Ex. 1-8. "Von Gott will ich nicht lassen," p. -

Concise Manual of Harmony, Intended for the Reading of Spiritual Music in Russia (1874)

Gamut: Online Journal of the Music Theory Society of the Mid-Atlantic Volume 7 Issue 1 Article 3 May 2014 Concise Manual of Harmony, Intended for the Reading of Spiritual Music in Russia (1874) Piotr Illyich Tchaikovsky Liliya Shamazov (ed. and trans.) Stuyvesant High School, NYC, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/gamut Part of the Composition Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Theory Commons, and the Slavic Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Tchaikovsky, Piotr Illyich and Shamazov, Liliya (ed. and trans.) (2014) "Concise Manual of Harmony, Intended for the Reading of Spiritual Music in Russia (1874)," Gamut: Online Journal of the Music Theory Society of the Mid-Atlantic: Vol. 7 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/gamut/vol7/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Volunteer, Open Access, Library Journals (VOL Journals), published in partnership with The University of Tennessee (UT) University Libraries. This article has been accepted for inclusion in Gamut: Online Journal of the Music Theory Society of the Mid-Atlantic by an authorized editor. For more information, please visit https://trace.tennessee.edu/gamut. CONCISE MANUAL OF HARMONY, INTENDED FOR THE READING OF SPIRITUAL MUSIC IN RUSSIA (1874) PIOTR ILLYICH TCHAIKOVSKY he presented study is nothing more than a reduction of my Textbook of Harmony T written for the theoretical course at the Moscow Conservatory. While constructing it, I was led by the desire to facilitate the conscious attitude of choir teachers and Church choir directors towards our Church music, while not interfering by any means into the critical rating of the works of our spiritual music composers. -

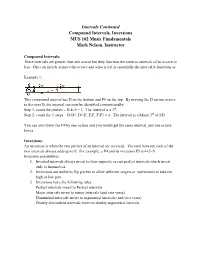

Intervals Continued Compound Intervals, Inversions MUS 102 Music Fundamentals Mark Nelson, Instructor

Intervals Continued Compound Intervals, Inversions MUS 102 Music Fundamentals Mark Nelson, Instructor Compound Intervals: These intervals are greater than one octave but they function the same as intervals of an octave or less. One can merely remove the octave and what is left is essentially the interval it functions as. Example 1: This compound interval has D on the bottom and F# on the top. By moving the D up one octave to the next D, the interval can now be identified conventionally: Step 1: count the pitches – D-E-F = 3. The interval is a 3rd. Step 2: count the ½ steps – D-D#, D#-E, E-F, F-F# = 4. The interval is a Major 3rd or M3. You can also lower the F# by one octave and you would get the same interval, just one octave lower. Inversions: An inversion is when the two pitches of an interval are reversed. The total between each of the two intervals always adds up to 9. For example, a P4 and its inversion P5 is 4+5=9. Inversion possibilities: 1. Inverted intervals always invert to their opposite except perfect intervals which invert only to themselves. 2. Inversions are useful to flip pitches to allow different singers or instruments to take the high or low part. 3. Inversions have the following rules: Perfect intervals invert to Perfect intervals Major intervals invert to minor intervals (and vise versa) Diminished intervals invert to augmented intervals (and vice versa) Doubly diminished intervals invert to doubly augmented intervals. Chart of Interval Inversions Perfect, Minor, Major, Diminished and Augmented Perfect Unison Perfect -

Interval Size and Affect: an Ethnomusicological Perspective

Empirical Musicology Review Vol. 7, No. 3-4, 2012 Interval Size and Affect: An Ethnomusicological Perspective SARHA MOORE The University of Sheffield ABSTRACT: This commentary addresses Huron and Davis’s question of whether “The Harmonic Minor Provides an Optimum Way of Reducing Average Melodic Interval Size, Consistent with Sad Affect Cues” within any non-Western musical cultures. The harmonic minor scale and other semitone-heavy scales, such as Bhairav raga and Hicaz makam, are featured widely in the musical cultures of North India and the Middle East. Do melodies from these genres also have a preponderance of semitone intervals and low incidence of the augmented second interval, as in Huron and Davis’s sample? Does the presence of more semitone intervals in a melody affect its emotional connotations in different cultural settings? Are all semitone intervals equal in their effect? My own ethnographic research within these cultures reveals comparable connotations in melodies that linger on semitone intervals, centered on concepts of tension and metaphors of falling. However, across different musical cultures there may also be neutral or lively interpretations of these same pitch sets, dependent on context, manner of performance, and tradition. Small pitch movement may also be associated with social functions such as prayer or lullabies, and may not be described as “sad.” “Sad,” moreover may not connote the same affect cross-culturally. Submitted 2012 Nov 24; accepted 12 December 2012. KEYWORDS: sad, harmonic minor, Phrygian, Hicaz, Bhairav, Yishtabach HURON and Davis’s article states that major scale melodies, on having their third and sixth degrees flattened, contain smaller intervals on average, and that if small pitch movement connotes “sadness,” then altering a standard major melody to the harmonic minor is “among the very best pitch-related transformations that can be done to modify a major-mode melody in order to render a sad affect” (p. -

COMPUTATIONAL ANALYSIS of QUARTER-TONE COMPOSITIONS by CHARLES IVES and IVAN WYSCHNEGRADSKY a Thesis Submitted to the College Of

COMPUTATIONAL ANALYSIS OF QUARTER-TONE COMPOSITIONS BY CHARLES IVES AND IVAN WYSCHNEGRADSKY A thesis submitted to the College of the Arts of Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Andrew M. Blake May 2020 Table of Contents Page List of Figures ................................................................................................................................. v List of Tables ................................................................................................................................. vi CHAPTER I .................................................................................................................................... 1 INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 1 The Quarter-Tone System ........................................................................................................... 1 Notation and Intervals ............................................................................................................. 2 Ives’ Some Quarter-Tone Impressions ........................................................................................ 4 Wyschnegradsky’s Manual of Quarter-Tone Harmony .......................................................... 6 Approaches to Analysis of Quarter-Tone Music ....................................................................... 10 The Place of Quarter-Tones in the Harmonic Series ................................................................ -

Music Theory Contents

Music theory Contents 1 Music theory 1 1.1 History of music theory ........................................ 1 1.2 Fundamentals of music ........................................ 3 1.2.1 Pitch ............................................. 3 1.2.2 Scales and modes ....................................... 4 1.2.3 Consonance and dissonance .................................. 4 1.2.4 Rhythm ............................................ 5 1.2.5 Chord ............................................. 5 1.2.6 Melody ............................................ 5 1.2.7 Harmony ........................................... 6 1.2.8 Texture ............................................ 6 1.2.9 Timbre ............................................ 6 1.2.10 Expression .......................................... 7 1.2.11 Form or structure ....................................... 7 1.2.12 Performance and style ..................................... 8 1.2.13 Music perception and cognition ................................ 8 1.2.14 Serial composition and set theory ............................... 8 1.2.15 Musical semiotics ....................................... 8 1.3 Music subjects ............................................. 8 1.3.1 Notation ............................................ 8 1.3.2 Mathematics ......................................... 8 1.3.3 Analysis ............................................ 9 1.3.4 Ear training .......................................... 9 1.4 See also ................................................ 9 1.5 Notes ................................................