Pentecostal Politics in Democratic Brazil a Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study of the Charismatic Movement in Portugal with Particular Reference To

A STUDY OF THE CHARISMATIC MOVEMENT IN PORTUGAL WITH PARTICULAR REFERENCE TO THE FRATERNAL ASSOCIATION by FERNANDO CALDEIRA DA SILVA Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF THEOLOGY in the subject CHURCH HISTORY at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: DR M H MOGASHOA FEBRUARY 2006 Table of Contents Thesis: A STUDY OF THE CHARISMATIC MOVEMENT IN PORTUGAL WITH PARTICULAR REFERENCE TO THE FRATERNAL ASSOCIATION Page Introduction 1 Chapter 1: A survey of the various forms of Christianity in Portugal 11 1.1 The establishment of Christianity in Spain and Portugal up to the Reformation 11 1.1.1 Establishment of Christianity in the Iberian Peninsula 12 1.1.2 Four main forces that led the people of the Iberian Peninsula to be attached to Roman Catholicism, as against any non-Roman Catholic Christian churches 14 1.1.3 Islamic influence on the Portuguese characteristic resistance to change, as related to non-Roman Catholic Christians 16 1.1.4 Involvement of the Pope in the independence of Portugal 17 1.2 Portugal and Europe from 1383 to 1822 18 1.2.1 A new era resulting from the revolution of 1383-1385 19 1.2.2 The Portuguese involvement in the crusades 21 1.2.3 Movements transforming the societies of Europe 21 1.2.4 Political, economic and socio-religious conditions in Portugal 23 1.2.4.1 The political conditions 23 1.2.4.2 The economic conditions 29 1.2.4.3 The socio-religious conditions 33 1.3 Reformation and Protestant influence in the Portuguese Empire 34 1.3.1 Signs of impact of the Reformation in Portugal -

Primórdios Da Igreja Evangélica Assembleia De Deus Em Roraima: Fundação E Consolidação (1915 – 1925) Primords of The

PRIMÓRDIOS DA IGREJA EVANGÉLICA ASSEMBLEIA DE DEUS EM RORAIMA: FUNDAÇÃO E CONSOLIDAÇÃO (1915 – 1925) PRIMORDS OF THE EVANGELICAL CHURCH ASSEMBLY OF GOD IN RORAIMA: FOUNDATION AND CONSOLIDATION (1915 - 1925) Erasmo Magno da Silva Melo1 Eduardo Gomes da Silva Filho2 Resumo O artigo busca fazer uma discussão sobre os primórdios da Igreja Evangélica Assembleia de Deus em Roraima, a partir da sua fundação e consolidação, entre 1915 e 1925. A princípio, buscamos realizar uma análise sobre a expansão da mensagem pentecostal em todo o Brasil e a sua chegada ao Estado de Roraima, enfatizando o pioneirismo da obra e analisando ainda a migração do seu precursor Cordulino Teixeira Bastos de Itapajé – Ceará – às terras roraimenses. Em seguida, detalharemos como ocorreu a fundação da Igreja Assembleia de Deus em Roraima e apontaremos as primeiras conversões ao pentecostalismo. Neste ponto, falaremos também sobre como aconteceu o processo de conversão para um indivíduo se tornar membro desta Igreja. Por fim, mostraremos a consolidação, o crescimento da obra pentecostal e os frutos deixados por cada líder. Palavras-chave: Igreja Assembleia de Deus. Pentecostalismo. Roraima. Cordulino Teixeira Bastos. Conversão. Abstract The article seeks to discuss the beginnings of the Evangelical Church Assembly of God in Roraima, from its foundation and consolidation, between 1915 and 1925. At first, we sought to carry out an analysis on the expansion of the pentecostal message throughout Brazil and the its arrival in the State of Roraima, emphasizing the pioneering nature of the work and also analyzing the migration of its precursores Cordulino Teixeira Bastos de Itapajé - Ceará - to the lands of Roraima. -

Rc: 47718 - Issn: 2448-0959

Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo do Conhecimento - RC: 47718 - ISSN: 2448-0959 https://www.nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/teologia/assembleia-de-deus Igreja Assembleia de Deus do Brasil de Corumbá: Uma igreja atuante na região do Pantanal ARTIGO ORIGINAL OLIVEIRA, Marcelo Soares de [1], GOMES, Kleber [2] OLIVEIRA, Marcelo Soares de. GOMES, Kleber. Igreja Assembleia de Deus do Brasil de Corumbá: Uma igreja atuante na região do Pantanal. Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo do Conhecimento. Ano 05, Ed. 03, Vol. 10, pp. 168-181. Março de 2020. ISSN: 2448-0959, Link de acesso: https://www.nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/teologia/assembleia-de-deus RESUMO O objetivo deste artigo é descrever um breve histórico da Igreja Evangélica Assembleia de Deus em Corumbá e seu papel de relevância na região. Destaca-se o fato que o trabalho se iniciou em Corumbá- MS em 1941, e no decorrer da trajetória este ministério se fez presente na região com ampliação da obra e atividades assistenciais. As fontes de pesquisas utilizadas foram os livros atas, documentação do memorial da igreja, entrevista realizada com pastor presidente em exercício e além de sites. Foi realizada uma pesquisa qualitativa de dados, através da análise bibliográfica dos materiais da igreja e entrevista. Este material poderá servir como fonte de consulta para os futuros estudantes o artigo não esgota o tema em questão, mas aborda de maneira resumida o papel histórico da Igreja. Palavras-chave: Almas, assistência, ensino. 1. INTRODUÇÃO O artigo abordará a influência e um sucinto histórico da Igreja Evangélica Assembleia de Deus no Brasil em Corumbá-MS, para a região do pantanal e a fronteiriça (BRASIL-BOLIVIA)[3], bem como sua importância. -

Adrien 2014.Pdf

UNIVERSIDADE METODISTA DE SÃO PAULO FACULDADE DE HUMANIDADE E DIREITO PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM CIÊNCIAS DA RELIGIÃO IGREJA UNIVERSAL DO REINO DE DEUS NA ÁFRICA SUBSAARIANA: IMPLANTAÇÃO, EXPANSÃO E TRANSNACIONALIZAÇÃO. ADRIEN GYATO BOWANE SÃO BERNARDO DO CAMPO 2014 IGREJA UNIVERSAL DO REINO DE DEUS NA ÁFRICA SUBSAARIANA: Implantação, expansão e transnacionalização ADRIEN GYATO BOWANE Dissertação apresentada em cumprimento às exigências do Programa de Pós-graduação em Ciências da Religião, para obtenção do grau de mestre. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Leonildo Silveira Campos SÃO BERNARDO DO CAMPO 2014 FICHA CATALOGRÁFICA G996i Gyato Bowane, Adrien Igreja Universal do Reino de Deus na Àfrica subsaariana : implantação expansão e transnacionalização / Adrien Gyato Bowane -- São Bernardo do Campo, 2014. 228fl. Dissertação (Mestrado em Ciências da Religião) – Faculdade de Humanidades e Direito, Programa de Pós-Graduação Ciências da Religião da Universidade Metodista de São Paulo, São Bernardo do Campo Bibliografia Orientação de: Leonildo Silveira Campos 1. Igreja Universal do Reino (IURD) - África 2. Pentecostalismo - África 3. Neopentecostalismo – Àfrica 4. Igrejas Independentes Africanas (IIA) I. Título CDD 289.9 A dissertação de mestrado sob o tílulo “ Igreja Universal do Reino de Deus na África subsaariana: implantação, expansão e transnacionalização”, elaborada por Adrien Gyato Bowane, foi apresentada em 02 de outubro de 2014, perante a banca examinadora composta por Prof. Dr. Leonildo Silveira Campos (Presidente UMESP), Profª Drª Sandra Duarte de Souza (Titular-UMESP) e Profª Drª Patrícia Teixeira Santos (Titular-UNIFESP). Professor Dr. Leonildo Silveira Campos Orientador e Presidente da Baca Examinadora Professor Dr. Helmut Renders Coordenador do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências da Religião Programa: Ciências da Religião Área de Concentração: Religião, sociedade e cultura Linha de pesquisa: Religião e dinâmicas sócio-culturais GYATO, Bowane Adrien. -

Formação Teológico-Pastoral Na Tradição Das Assembleias De Deus: Experiências, Ênfases E Desafios

Formação teológico-pastoral na tradição das Assembleias de Deus: experiências, ênfases e desafios Pastoral theological formation in the tradition of the Assembleship of God: experiences, accents and challenges Formación teológico-pastoral en la tradición de las Asambleas de Dios: experiencias, énfasis y desafíos Ricardo Bitun RESUMO O presente artigo propõe uma reflexão sobre a formação teológico-pastoral das Assembleias de Deus no Brasil. Com um conciso histórico do seu início e a tradição deixada por seus fundadores suecos, procura-se mostrar de que maneira a cosmovisão dos fundadores influenciou sua formação teológica. Pontua-se sua principal ênfase doutrinária – o Batismo no Espírito Santo – e sua aversão ao estudo sistemático das Escrituras. Palavras-chave: Assembleia de Deus; doutrina, teologia ABSTRACT The present article intends to be a reflection on the theological and pastoral formation of the Assembly of God Church in Brazil. With a concise description of their beginning and the heritage left by the Swedish founders, and the demonstra- tion of how the cosmovision of the referred founders have influenced their theo- logical formation. It has been also pointed out their main doctrinal emphasis – the baptism with the Holy Spirit – as well as their averseness to the systematic study of The Scriptures. Keywords: Assembly of God, doctrine, theology RESUMEN El presente artículo es una breve reflexión sobre la formación teológico-pastoral de las Asambleas de Dios en el Brasil. Con una concisa sinopsis histórica de sus comienzos y de la tradición que sus fundadores suecos dejaron, procuramos demostrar de qué manera la cosmovisión de sus fundadores influenció la formación teológica de la iglesia. -

Revista a Seara E O Debate Sobre a Inserção Da Igreja Assembleia De Deus Na Política Partidária (1956-1958), P

Revista Brasileira de História das Religiões. ANPUH, Ano XIII, n. 37, Maio/Agosto de 2020 - ISSN 1983-2850 / Revista A Seara e o debate sobre a inserção da Igreja Assembleia de Deus na política partidária (1956-1958), p. 177-217 / Revista A Seara e o debate sobre a inserção da Igreja Assembleia de Deus na política partidária (1956-1958) André Dioney Fonseca 1 DOI: https://doi.org/10.4025/rbhranpuh.v13i37.52164 Resumo: Este artigo tem como objetivo analisar a iniciativa pioneira de João Pereira de Andrade e Silva e Joanyr de Oliveira no fomento ao debate sobre a relação entre Igreja e política nas páginas de A Seara, revista que teve sua circulação iniciada em setembro de 1956 pela Casa Publicadora das Assembleias de Deus (CPAD). Nossa intenção é demonstrar que, embora a maioria da liderança da Assembleia de Deus (AD) fosse, naquele contexto, hostil à participação da Igreja na arena política, havia alguns membros e líderes que viam sua inserção no âmbito político como algo urgentemente necessário. Mostraremos também que a reação da CPAD, em face desse ousado projeto editorial de A Seara, foi bastante contundente, resultando no desmonte da equipe que havia desenhado as linhas editoriais mestras do periódico, quando de sua fundação. A importância dessa reflexão está na possibilidade de podermos conhecer uma importante faceta da história da relação da AD com a política que ainda foi muito pouca estudada, levando-se em consideração que a maioria das pesquisas sobre as articulações eleitorais dessa Igreja está concentrada no contexto de abertura democrática dos anos 1980, e que os poucos trabalhos que pretenderam analisar as relações da AD com o mundo da política, antes desse período, deram destaque às vozes predominantes, que defendiam uma postura de respeito da Igreja aos “poderes temporais”, sem qualquer inserção político-partidária. -

A Chronology of Protestant Beginnings: Brazil

A CHRONOLOGY OF PROTESTANT BEGINNINGS: BRAZIL By Clifton L. Holland, Director of PROLADES (Last revised on 31 October 2017) Brief Historical Overview of Brazil: Discovered by Spanish explorer Vicente Yanez Pinzón but Spain made no claim to this 26 January territory. 1500 Discovered by Portuguese explorer Pedro Álvares de Cabral who claimed the territory for the 24 April 1500 King of Portugal. Became Portuguese Colony 1511 Period of Brazilian Monarchy: son of Portuguese king declares independence from Portugal 1822-1889 and crowns himself Peter I, Emperor of Brazil. Monarchy overthrown, federal republic established with central government controlled by 1889 coffee interests. Religious Liberty established. 1891 Number of North American mission agencies in 1989 165 Number of North American mission agencies in 1996 124 Number of North American mission agencies in 2006 152 Indicates European missionary society* Significant Protestant Beginnings: Pre-1900 Period 1555-1566 - *French Huguenot colony (Calvinists) established under French commander Nicolas Durand de Villegaignon; the first Protestant worship service was held in Brazil on 10 March 1557; the French were expelled by the Portuguese in 1566. 1624-1654 - *Dutch colony (Calvinists) and mission efforts on Northeast coast at Recife; the Dutch were expelled by the Portuguese in 1654. 1816 - *First Anglican chaplain arrived in Brazil at Rio de Janeiro; Robert C. Crane. 1817 - *British and Foreign Bible Society colporteurs 1822 - *First Anglican chapel was dedicated on 26 May in Rio de Janeiro to serve the expatriate community of mostly British citizens. 1824 - First German Lutheran immigrants arrived in the Southern Region at São Leopoldo, Rio Grande do Sul, and Blumenan, Santa Catarina; first Lutheran Church was established at Nova Friburgo, Rio de Janeiro. -

Exporting Christianity: Governance and Doctrine in the Globalization Of

Preliminary Exporting Christianity: Governance and Doctrine in the Globalization of US Denominations Gordon H. Hanson UC San Diego and NBER Chong Xiang Purdue University and NBER July 2010 Abstract. In this paper we build a model of competition between religious denominations based on Aghion and Tirole (1997) and Iannaccone (1992), in which we treat denominations akin to multinational enterprises. The model yields predictions for how a denomination’s religious doctrine and organizational structure affect its ability to attract adherents, depending on country characteristics including distance from the denomination headquarters, and the availability of social services provided by the government. We test these predictions using data from the World Christian Database. We find that the denominations with a decentralized structure have larger membership and build more congregations in the countries that are farther away from the denomination headquarter and/or have less developed communication infrastructure. We also find that the denominations with a strict doctrine do better in the countries in which the government supplies less in the way of health and other social services. These findings are consistent with the predictions of our model. They also shed light on the factors that affect the rapid expansion of Protestant denominations around the globe in the past 40 years. We thank Oana Hirakawa, Kanako Hotta, Lyndsay Oldenski, and, especially, Chase Stafford for research assistance and the National Science Foundation and the Center on Pacific Economies at UCSD for financial support. 1. Introduction In non-western countries, the practice of Christianity has long been dominated by the historical church or churches associated with current or former colonial powers. -

Religious Values and Development in Brazil

1 Gustavo Di Santo Religious values and development in Brazil. • Questions of research This work tries to verify the convergence/divergence of the behaviors and attitudes toward the socio-economic development1, expressed by the believers who belong to the Catholics Church compared with the believers who are members of the Evangelical Pentecostal denominations, through the case of study of Brazil. The same relation is analyzed with respect to the people who are not member of any religious groups in comparison with the individuals that belongs to a religious movement inside the Catholics and Evangelical Pentecostal world. • Epistemological foundations This work is based on the following axioms at the epistemological level: o All scientific productions are related to a “state of arts” which confer legitimacy to a new work inside the academic field2 (ex nihilo nihil fit) o All scientific works are the product of the cultural context (environment) and the creative act of the author. o A scientific work is always a partial, relative and unique perspective about a phenomenon (either social or natural3). It is a partial perspective since the analysis is made through the rules that are valid in the scientific system, which may not be recognized as valid in other systems (i.e. religious system) that use their own criteria to observes a specific phenomenon It is a specific perspective since the analysis can adopt a particular theoretical model, inside the scientific system to interpret a phenomenon; it is a unique perspective, since the work depends on the creative act of the researcher. For these reasons I assume valid the affirmation: “all that is said is said by an observer”4. -

MIOLOFRIDA Web.Pdf

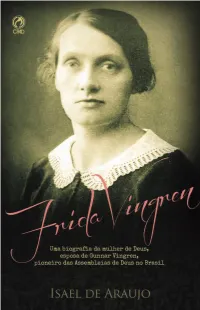

Uma biografia da mulher de Deus, esposa de Gunnar Vingren, pioneiro das Assembleias de Deus no Brasil Isael de Araujo 1ª edição Rio de Janeiro 2014 Todos os direitos reservados. Copyright © 2014 para a língua portuguesa da Casa Publicadora das Assembleias de Deus. Aprovado pelo Conselho de Doutrina. Preparação dos originais: Daniele Pereira Revisão: Verônica Araujo Capa: Jonas Lemos Editoração: Fábio Longo As citações bíblicas foram extraídas da versão Almeida Revista e Corrigida, edição de 1995, da Sociedade Bíblica do Brasil, salvo indicação em contrário. Para maiores informações sobre livros, revistas, periódicos e os últimos lançamentos da CPAD, visite nosso site: http://www.cpad.com.br. SAC — Serviço de Atendimento ao Cliente: 0800-021-7373 Casa Publicadora das Assembleias de Deus Av. Brasil, 34.401, Bangu, Rio de Janeiro – RJ CEP 21.852-002 1ª edição: Janeiro/2014 Tiragem: 3.000 M827 Moraes, Isael Araujo de, 1963 – Frida Vingren: uma biografia da mulher de Deus, esposa de Gunnar Vingren, pioneiro das Assembleias de Deus no Brasil / Isael de Araujo. – Rio de Janeiro: CPAD, 2014. 183p. : il. ; 23cm. ISBN: 9788526311503 CDD 922.89 Vingren, Frida, 1891-1940. 2. Assembleia de Deus – liderança ministerial – Biografia. 3. Missionários – Biografia. I. Título. AGRADECIMENTOS Minha gratidão ao remanescente dos Vingren pela inestimável ajuda nas pesquisas em minha visita à Suécia em 2008: a Margit (in memoriam), pela entrevista concedida e pelas fotos inéditas; a Sueli pelas fotos e materiais históricos; a Lars-Ivar Roland pelas visitas aos locais relacionados aos últimos anos de sua avó; e a Bertil pela doação de fotos e pela entrevista concedida. -

History of Assemblies of God Ghana Pdf

History of assemblies of god ghana pdf Continue The Assembly of God was founded in 1914 in Hot Springs, Arkansas with 300 people at the constituent convention. Today, there are about 13,000 churches in the United States with more than 3 million members and followers. There are more than 69 million assembly members of God around the world, making the Assembly of God the largest Pentecostal denomination in the world. The U.S. National Office of the God Assemblies is located at 1445 N. Boonville Avenue, Springfield, Missouri. It houses the executive and administrative offices of scholarships, service departments and departments, as well as warehouses. For other purposes, see the Assemblies of God (disambigation). A/G redirects here. For the ratio of blood test A/G see Albumin and Globulin. Assemblies of GodClassificationProtesterTheologyPenstinTorcoperative BodyChairmanGeorge O. Wood (2017-2020) 1Region190 CountriesOrigin1914 (WAGF officially established 1988)Congregation375.310'2'Members69.200,000'2'Official website Of God 'AG', officially World Collections of God Scholarships, is a group of more than 144 autonomous, self-governing national groups of churches, which together form the world's largest Pentecostal denomination. It is the fourth largest international Christian group of denominations. As an international community, member denominations are completely independent and autonomous, but they share common beliefs and history. The congregation emerged from Azusa Street Revival in the early 20th century. This renaissance led to the creation of the Assemblies of God in the United States in 1914. Through foreign missionary work and the establishment of relations with other Pentecostal churches, the Assembly of God has become a worldwide movement. -

Doran-Mastersreport-2013

Copyright by Justin Michael Doran 2013 The Report Committee for Justin Michael Doran Certifies that this is the approved version of the following report: Demon-Haunted Worlds: Enchantment, Disenchantment, and the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: Thomas A. Tweed Virginia Garrard-Burnett Demon-Haunted Worlds: Enchantment, Disenchantment, and the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God by Justin Michael Doran Report Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2013 Dedication For Jenny and her patience. Acknowledgements I would like to thank Adrian Masters for his help transcribing testimonio videos from Spanish. I would also like to thank my two readers, Thomas Tweed and Virginia Garrard-Burnett for their help in revising earlier drafts of this report. Part of this research was funded by a Foreign Language and Area Studies grant provided by the U.S. government and administered by the Teresa Lozano Long Institute of Latin American Studies at the University of Texas. Finally, I would like to thank Katharine Batlan and the Works-in-Progress committee of the Graduate Committee for the Study of Religion at the University of Texas for their helpful comments. v Abstract Demon-Haunted Worlds: Enchantment, Disenchantment, and the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God Justin Michael Doran, M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2013 Supervisor: Thomas A. Tweed This report analyzes the Igreja Universal do Reino de Deus (Universal Church of the Kingdom of God)—a Brazilian neo-Pentecostal church—by its capacity to enchant everyday life in modern, disenchanted worlds.