Working for the Local Community; Accounting for Substantively Broader and Geographically Narrower Corporate and Social Responsibility

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Units To

NEW UNITS TO LET 5,869 to 45,788 sq ft (545 to 4,254 sq m) A new development of industrial/warehouse units situated in a prime location on the Brimsdown Industrial Area in Enfield, North London. www.enfieldthegrid.com ONLY FOUR UNITS REMAINING LOCKFIELD AVENUE | ENFIELD | EN3 7PX A range of flexible units ideally suited for serving the North and Central London markets and the wider South East Enfield’s strategic location with easy access to the M25 and A406, plus Central London, London airports and public transport network has attracted a diverse industrial and distribution base. It is home to over 10,000 logistics and industrial businesses employing nearly 90,000 people. Accommodation Terms General specification Unit Ground First TOTAL* The units are available on new leases with full terms • 8.4m clear internal height No. Floor (sq ft) Floor (sq ft) (sq ft) upon application. • Full height electric loading doors 1 LET 24,696 • 37.5kN per sq m floor loading 104 LET 15,070 • Fully fitted first floor offices 90 5,278 1,243 6,521 • Gated secure estate 92 5,510 1,298 6,808 Sliding Gate • 3 phase power supply 94 4,750 1,119 5,869 • Potential for mezzanine floors 96 4,790 1,129 5,919 98 UNDER OFFER 6,337 36m 100 LET 6,743 102 LET 7,591 Green credentials TOTAL 85,554 The scheme employs the latest environmentally friendly technologies *Areas are approximate on a GEA basis. to reduce the costs of occupation and will ensure a minimum 35% Units can be combined. -

Employment & Regeneration in LB Enfield

Employment & Regeneration in LB Enfield September 2015 DRAFT 1 Introduction • LB Enfield and Enfield Transport Users Group (ETUG) have produced a report suggesting some large scale alterations to the bus network. One of the objectives of the report is to meet the demands of the borough’s housing and regeneration aspirations. • TfL have already completed a study of access to health services owing to a re-configuration of services between Chase Farm, North Middlesex and Barnet General Hospital and shared this with LB Enfield. • TfL and LB Enfield have now agreed to a further study to explore the impact of committed development and new employment on bus services in the borough as a second phase of work. 2 DRAFT Aims This study will aim to: •Asses the impact of new housing, employment and background growth on the current network and travel patterns. •Highlight existing shortfalls of the current network. •Propose ideas for improving the network, including serving new Developments. 3 DRAFT Approach to Study • Where do Enfield residents travel to and from to get to work? • To what extent does the coverage of the bus network match those travel patterns? • How much do people use the bus to access Enfield’s key employment areas and to what extent is the local job market expected to grow? • What are the weaknesses in bus service provision to key employment areas and how might this be improved? • What is the expected growth in demand over the next 10 years and where are the key areas of growth? • What short and long term resourcing and enhancements are required to support and facilitate growth in Enfield? 4 DRAFT Methodology •Plot census, passenger survey and committed development data by electoral ward •Overlay key bus routes •Analyse existing and future capacity requirements •Analyse passenger travel patterns and trip generation from key developments and forecast demand •Identify key issues •Develop service planning ideas 5 DRAFT Population Growth According to Census data LB Enfield experienced a 14.2% increase in population between 2001 and 2011 from 273,600 to 312,500. -

Services Between Enfield Lock and Tottenham Hale

Crossrail 2 factsheet: Services between Enfield Lock and Tottenham Hale New Crossrail 2 services are proposed to serve Tottenham Hale, Northumberland Park, Angel Road, Ponders End, Brimsdown and Enfield Lock, with between 10 and 12 trains per hour in each direction operating directly to, and across, central London. What is Crossrail 2? Why do we need Crossrail 2? Crossrail 2 is a proposed new railway serving London and On the West Anglia Main Line, local stopping services and the wider South East that could be open by 2030. It would faster services from Cambridge and Stansted Airport all connect the existing National Rail networks in Surrey and compete for space on the line. This limits the number of Hertfordshire with trains running through a new tunnel trains that can call at local stations, and extends journey from Wimbledon to Tottenham Hale and New Southgate. times to and from the area. Crossrail 2 will connect directly with National Rail, Liverpool Street and Stratford stations also currently face London Underground, London Overground, Crossrail 1, severe capacity constraints. It is forecast that by 2043 High Speed 1 international and domestic and High Speed 2 demand for rail travel on this line will have increased by 39%. services, meaning passengers will be one change away There is currently no spare capacity for additional services. from over 800 destinations nationwide. Crossrail 2 provides a solution. It would free up space on the railway helping to reduce journey times for longer distance Crossrail 2 in this area services, and would enable us to run more local services to central London. -

Foodbank in Demand As Pandemic Continues

ENFIELD DISPATCH No. 27 THE BOROUGH’S FREE COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER DEC 2020 FEATURES A homelessness charity is seeking both volunteers and donations P . 5 NEWS Two new schools and hundreds of homes get go-ahead for hospital site P . 6 ARTS & CULTURE Enfield secondary school teacher turns filmmaker to highlight knife crime P . 12 SPORT How Enfield Town FC are managing through lockdown P . 15 ENFIELD CHASE Restoration Project was officially launched last month with the first of many volunteering days being held near Botany Bay. The project, a partnership between environmental charity Thames 21 and Enfield Council, aims to plant 100,000 trees on green belt land in the borough over the next two years – the largest single tree-planting project in London. A M E E Become a Mmember of Enfield M Dispatch and get O the paper delivered to B your door each month E Foodbank in demand C – find out more R E on Page 16 as pandemic continues B The Dispatch is free but, as a Enfield North Foodbank prepares for Christmas surge not-for-profit, we need your support to stay that way. To BY JAMES CRACKNELL we have seen people come together tial peak in spring demand was Citizens Advice, a local GP or make a one-off donation to as a community,” said Kerry. “It is three times higher. social worker. Of those people our publisher Social Spider CIC, scan this QR code with your he manager of the bor- wonderful to see people stepping “I think we are likely to see referred to North Enfield Food- PayPal app: ough’s biggest foodbank in to volunteer – we have had hun- another big increase [in demand] bank this year, most have been has thanked residents dreds of people helping us. -

Winchmore Hill

Enfield Society News No. 194, Summer 2014 Enfield’s ‘mini-Holland’ project: for and against In our last issue we discussed some of the proposals in Enfield Council’s bid under the London Mayor’s “mini-Holland” scheme to make the borough more cycle-friendly. On 10th March the Mayor announced that Enfield was one of three boroughs whose bids had been selected and that we would receive up to £30 million to implement the project. This provides a great opportunity to make extensive changes and improvements which will affect everyone who uses our streets and town centres, but there is not unanimous agreement that the present proposals are the best way of spending this money. The Council has promised extensive consultations before the proposals are developed to a detailed design stage, but it is not clear whether there are conditions attached to the funds which would prevent significant departures from the proposals in the bid. The Enfield Society thinks that it would be premature to express a definitive view until the options have been fully explored, but we are keen to participate in the consultation process, in accordance with the aim in our constitution to “ensure that new developments are environmentally sound, well designed and take account of the relevant interests of all sections of the community”. We have therefore asked two of our members to write columns for and against the current proposals, in order to stimulate discussion. A third column, from the Enfield Town Conservation Area Study Group, suggests a more visionary transformation of Enfield Town. Yes to mini-Holland! Doubts about mini- Let’s start with the people of Enfield. -

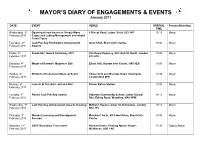

Mayor's Diary of Engagements & Events

MAYOR’S DIARY OF ENGAGEMENTS & EVENTS January 2017 DATE EVENT VENUE ARRIVAL Person Attending TIME Wednesday, 1st Opening of new business Simply Move 6 Biscot Road, Luton, Beds LU3 1AT 10:15 Mayor February 2017 Estate and Letting Management and Ababil Travel Tours Thursday, 2nd Jack Petchey Foundation Achievement Grand Hall, Brent Civic Centre 19:20 Mayor February 2017 Awards Friday, 3rd Graduates’ Award Ceremony 2017 The Royal Regency, 501 High St. North, London 19:00 Mayor February 2017 E12 6TH Saturday, 4th Mayor of Harrow's Mayoress Ball Elliott Hall, Harrow Arts Centre, HA5 4EA 19:00 Mayor February 2017 Sunday, 5th Enfield's Chickenshed Musical Event Chase Side and Bramley Road, Southgate, 19:30 Mayor February 2017 London N14 4PE. Monday, 6th Launch of St Luke's Jail and Bail Pinner Police Station 10:00 Mayor February 2017 Tuesday, 7th Attend Jack Petchey awards Alperton Community School, Lower School 18:15 Mayor February 2017 Site, Ealing Road, Wembley, HA0 4PW Wednesday, 8th Jack Petchey Achievement Awards Evening Millfield Theatre, Silver St, Edmonton, London 19:15 Mayor February 2017 N18 1PJ Thursday, 9th Member Learning and Development Members' Suite, 4th Floor Drum, Brent Civic 18:00 Mayor February 2017 Session Centre Saturday, 11th SSPC Education Trust event Navnat Centre, Printing House, Hayes, 17:30 Deputy Mayor February 2017 Middlesex UB3 1AR Monday, 13th Brent Community Transport new bus East Lane Business Park, 2 Lumen Road HA9 12:30 Mayor February 2017 launch 7RE Tuesday, 14th Basketmouth SSE Wembley Arena, Arena Square, -

58B Alexandra Road, Brimsdown, ENFIELD, EN3 7EH

Freehold Vehicle Repair Garage / Workshop For Sale - Enfield EN3 58b Alexandra Road, Brimsdown, ENFIELD, EN3 7EH Area Gross Internal Area: 305 sq.m. (3,282 sq.ft.) Price Guide Price £475,000 subject to contract Property Description The property comprises predominantly single storey motor-trade workshop and yard. The property is currently configured to accommodate a small customer and reception area, WCs and offices.There is a small mezzanine above the offices used for additional storage. The workshop has a spray booth & associated extraction, 2 x vehicle ramps and a ceiling mounted Reznor space heater, which we have been advised are all in working order. The workshop is accessed via a single electronically operated loading door. Key considerations > Rarely available freehold vehicle repair garage / workshop with vacant possession > Gross internal area: 304.97 sq.m (3,283 sq.ft) > Forecourt and side yard: 164.11 sq.m (1,766 sq.ft) > 2 x vehicle ramps and spay booth with extraction > Separate office, reception area, WCs and spray booth > Eaves Height 3.36 m. Apex 5.56 m > Electrically operated loading load 3.04 m high x 4.14 m wide > Medium term development potential with possible future redevelopment of the Alma Road Industrial Estate > Excellent transport communications > Great Cambridge Road (A10) 1.6 kilometres (0.99 miles) > M25 motorway 3.75 kilometres (2.33 miles) https://www.gilmartinley.co.uk/properties/for-sale/car-repairs/brimsdown/enfield/en3/27956 Our ref: 27956 Freehold Vehicle Repair Garage / Workshop For Sale - Enfield EN3 Accommodation Accommodation Area sq.m. Area sq.ft. Comments Ground Floor 284.87 3,066 Mezzanine 20.10 216 Forecourt and Side Yard 164.11 1,766 Property Location The subject property is located off the east of Alexandra Road via a vehicular accessway to the southern side of Blu- Ray House within the well established Alma Road Industrial Estate, only 3.0 kilometres (1.86 miles) to the east of Enfield Town Centre. -

Edmonton Cycle Club News

Edmonton Cycle Club News The Newsletter of the ECC and Enfield Cycling Campaign - LCC Autumn 2014 Newsletter No. 61 Welcome to the bumper-sized autumn issue. Hello – we hope you have enjoyed the summer! Please check website for regular updates to the diary. Do come to our Bike Maintenance sessions (B.M.W.s) and get the best tips and advice on keeping your bike in working order. New ideas for rides are welcome, as are new ride leaders – why not pair up with a regular leader to see how it’s done! Happy, safe cycling! - The Editors. Club Meetings / Socials: Welcome to new members: Thursdays at 8pm prompt Howard Oliver, Steve Grange, 2 Oct, 4 Dec, 5Feb: The Wheatsheaf pub room, Jerry Garvey, Mike Beale Baker Street, Enfield. Autumn Birthday wishes to: 6 Nov, 8 Jan*, 5 Mar: Sept : Winchmore Hill Sports Club 3 Rosa, 9 Chris L, 10 Evelyn, pavilion, Firs Lane N21. 12 Chris W, 13 Jacquie, 16 Graham, 18 Mary, 20 Jill, * Note is Second Thursday in Jan 23 Chris A. Octobre : B.M.W. Sessions: 5 Jayne, 9 Terry, 19 Ian, 24 Celine, Thursdays at 7.30pm 31 Angela Novembre : 18 Sept, 16 Oct, 20 Nov, 18 Dec, 15 Jan, 18 Andy Hw, Julian, 21 Nikki, Wayne, 19Feb: 28 Pat. Winchmore Hill Sports Club Decembre : pavilion, Firs Lane N21. 28 Gerry, 29 Angela, 31 Sibel. Enfield Cycling Campaign: Please Note: Meetings on 2 nd Thursdays If you wish to receive this newsletter by post, please send SAEs to Paul at 2 Venue & time T.B.C. -

New Units To

NEW UNITS TO LET 5,869 to 13,329 sq ft (545 to 1,238 sq m) A new development of industrial/warehouse units situated in a prime location on the Brimsdown Industrial Area in Enfield, North London. www.enfieldthegrid.com SECURE GATED SCHEME LOCKFIELD AVENUE | ENFIELD | EN3 7PX Sliding Gate A range of flexible units ideally suited for serving the North and Central London markets and the wider South East. BRANCROFT WAY Sliding Gate Enfield’s strategic location with easy access to the M25 and A406, plus Central London, London airports and public transport network has attracted a diverse industrial and distribution base. It is home to over 10,000 logistics and industrial businesses employing nearly 90,000 people. LOCKFIELD AVENUE Sliding Gate Accommodation Terms Green credentials Unit Ground First TOTAL* The units are available on new leases with full The scheme employs the latest environmentally friendly No. Floor (sq ft) Floor (sq ft) (sq ft) terms upon application. technologies to reduce the costs of occupation and will 90 5,278 1,243 6,521 ensure a minimum 35% decrease in CO2 emissions over 92 5,510 1,298 6,808 2010 Buildings Regulations. The units achieve a BREEAM 94 4,750 1,119 5,869 Planning use rating of “Excellent”. As a result occupation costs to the 96 4,790 1,129 5,919 B1 (c), B2 and B8 (industrial and warehouse) uses. end user will be reduced. BRANCROFT WAY 98 5,128 1,209 6,337 TOTAL 31,454 The green initiatives include: General specification • Photovoltaic panels 90&92** 10,788 2,541 13,329 • Gated secure estate • Low air permeability design * Areas are approximate on a GEA basis. -

Buses from Cockfosters

Buses from Cockfosters 298 Route 298 terminates at Potters Bar Station Key Potters Bar Mutton Lane Potters Bar on Monday to Friday evenings and at weekends Cranborne Road 298 Day buses in black Industrial Estate N91 Night buses in blue Potters Bar POTTERS BAR Lion —O Connections with London Underground o Connections with London Overground R Connections with National Rail Southgate Road M Mondays to Fridays daytime only Stagg Hill Slopers Pond Farm Red discs show the bus stop you need for your chosen bus Cockfosters Road service. The disc appears on the top of the bus stop in the Beech Hill street (see map of town centre in centre of diagram). Cockfosters Road Green Oak Place Cockfosters Road The yellow tinted area includes every Route finder Coombehurst Close bus stop up to about one-and-a-half miles from Cockfosters. Main stops Day buses Cockfosters Road are shown in the white area outside. Bus route Towards Bus stops Trent Country Park 307 Brimsdown 298 Arnos Grove +BDJ Castlewood Road Potters Bar +ACK B Cockfosters NT Green Street Grove Road ELMO A 299 Muswell Hill Broadway +BDE B C L Northfield Road O S Barnet Hospital +HL Westbrook Crescent E 307 Westbrook Square Hail & Ride Mount Pleasant ANT Hertford Road Brimsdown PLEAS W +EN section UNT ESTP MO OLE AV Barnet B ENU 384 Lawton Road C E Ponders End O G Westbrook Crescent C L K O Night buses FO U C K Stapylton Road S E T S E Southbury Road Baring Road E T N Bus route Towards Bus stops R E T Fordham Road S R Hail & Ride D UE C R G R ENFIELD N91 Trafalgar Square +BDE section EN O A -

Two Venues, Twice the Entertainment

THE SUMMER SEASON SUMMER 2013 TWO VENUES, TWICE THE ENTERTAINMENT As summer approaches and the days are getting longer, we’re looking forward to springing into a new season of great drama, music, comedy, poetry, jazz nights and even a series of films. The Dugdale Centre’s intimate studio space will play host to a season of outstanding theatre. Vamos Theatre Company will return with the funny and fearless masked performance Finding Joy and THURSDAY 25th - FRIDAY 26th APRIL 8PM we have an award winning new play from Emma Jowett, Snap. X AT DUGDALE CENTRE Catch. Slam. Photographer: David Jackson David Photographer: For the first time the Dugdale Centre will be staging two Greek events: a modern day version of Aristophanes’ play Wealth, a political satire on contemporary Athens, and stand up comedian Paul Lambis is sure to keep you entertained with tales about growing up in Cyprus. “It was the mischief Our season of jazz and poetry continues to flourish withZiggy’s we got up to World Jazz Club, The Sunday Edition and Jacqueline Saphra, and that kept us going” we’re screening classic films from across the world with cinema (Mary, Survivor 2011) group, Talkies. At Millfield Theatre local talent takes centre stage. Saint Monica’s Players will perform the hit musical Our House featuring the ska pop genius of Madness. The ever popular Haringey Shed return with two brand new shows and future stars from Performers Become A fan & have YOUR SAY College will showcase their dance and choreography skills. www.millfieldtheatre.co.uk Like us at Millfield -

Culture Connects Strategy 2020–25 (PDF)

A Cultural Strategy For Enfield 2020-2025 Dallas–Pierce–Quintero Poetry – Mary Duggan Contents Poetry grows, as a meadow of thought. Flowers from the legacy Foreword 4 of Keats and Lamb supported Our Cultural Vision for Enfield 6 by the local authority and literary initiative Where the ear can hear Executive Summary 8 that sullen craft* of poetry grows 1. A Cultural Strategy for Enfield 10 as reflective art for the ‘have-a -go’ The Value & Role of Culture who joins this community What We Mean by Culture constellation poetry grows Fostering a Healthy Cultural Ecology within our National Stanza group 2. Context 18 Library and borrowed book A Multi-faceted Borough The juggled word. That vibrato voice Culture & Diversity The meter, rhythm and rhyme, Cultural Landscape Opportunities to Grow Enfield’s Culture that translates form into diversity; Creative Enterprise Difference. Isolation. Minority Wider Opportunities As poetry grows in Enfield Responding to Covid-19 it shoulders grief and deeply feels Analysis / SWOT the use of this well-being; 3. Cultural Priorities 42 Expressing life and desire Sustainable Culture, Creating Opportunities for Petulant love, staged and at Young People, Culture Everyday local festival the poet grows 4. Focus Areas 46 in Enfield within an anthology On the Ground The published pamphlet. The Right Mix The exhibition. In local dedication Supporting Growth Celebrate when poetry grows Capacity a confident community. 5. Cultural Action Plan 70 Mary Duggan, Enfield Poet 2020 Cover; “Place We Call Home” by King Owusu, 2020 6. Investment & Implementation 80 Commissioned by Artist Hive Studios for the Enjoy Enfield Summer festival is association with Enfield Council.