Dynamic Slip Transfer from the Denali to Totschunda Faults, Alaska: Testing Theory for Fault Branching by Harsha S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Denali Fault System of Southern Alaska an Interior Strikeslip

TECTONICS, VOL. 12, NO. 5, PAGES 1195-1208, OCTOBER 1993 DENALl FAULT SYSTEM OF SOUTHERN 1974; Lanphere,1978; Stoutand Chase,1980]. Despitethis ALASKA: AN INTERIOR STRIKE.SLIP consensus,the tectonichistory of the DFS remainsrelatively STRUCTURE RESPONDING TO DEXTRAL unconstrained.Critical outcrops are rare, access is difficult,and AND SINISTRAL SHEAR COUPLING to this day muchof the regionis incompletelymapped at detailed scales. Grantz[1966] named or redefinedsix individualfault ThomasF. Redfieldand Paul G. Fitzgerald1 segmentscomprising the DFS. From west to eastthe Departmentof Geology,Arizona State University, segmentsare the Togiak/Tikchikfault, the Holitnafault, the Tempe Farewellfault, the Denali fault (subdividedinto the McKinley andHines Creek strands), the Shakwakfault, andthe Dalton fault (Figure 1). At its westernend, the DFS is mappednot as a singleentity but ratherappears to splayinto a complex, Abstract.The Denalifault system (DFS) extendsfor-1200 poorlyexposed set of crosscuttingfault patterns[Beikman, km, from southeastto southcentral Alaska. The DFS has 1980]. Somewhatmore orderly on its easternend, the DFS beengenerally regarded as a fight-lateralstrike-slip fault, along appearsto join forceswith the ChathamStrait fault. This which postlate Mesozoicoffsets of up to 400 km havebeen structurein turn is truncatedby the Fairweatherfault [Beikman, suggested.The offsethistory of the DFS is relatively 1980],the present-dayNorth American plate Pacific plate unconstrained,particularly at its westernend. For thisstudy boundary[Plafker -

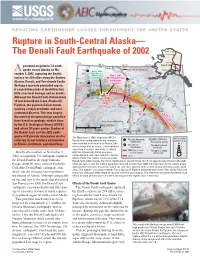

Rupture in South-Central Alaska— the Denali Fault Earthquake of 2002

REDUCING EARTHQUAKE LOSSES THROUGHOUT THE UNITED STATES Rupture in South-Central Alaska— ������� ��� The Denali Fault Earthquake of 2002 ��� �������� � � � � � � ��� ��������� �� ����� powerful magnitude 7.9 earth- ����� ����� ����� ���� �� ��� ������ quake struck Alaska on No- ����� ������������ ��� �������� ��������� A ��� ��� ���� � ���� ������ ������ � � � vember 3, 2002, rupturing the Earth’s � � �������� ��� �� ���� � � � � surface for 209 miles along the Susitna � ���������� ���� ������ ����� � � ����� � � ���������� Glacier, Denali, and Totschunda Faults. � � ����� � � � ��������� �� � � � � � Striking a sparsely populated region, � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � it caused thousands of landslides but � � � � � � � � � � little structural damage and no deaths. � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � Although the Denali Fault shifted about � �������� ������� � � ��� � � � � ������� � � 14 feet beneath the Trans-Alaska Oil ��������� �� � ����� � Pipeline, the pipeline did not break, � � ���� � � � � � � ������ � � � � � � � � �������� averting a major economic and envi- � � ���� � ��������� �� � ronmental disaster. This was largely � � � � � � � the result of stringent design specifica- � � � � � � � � tions based on geologic studies done ������������ ��� �������� � � � � � � � by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) � �� ��� ���������� � � � and others 30 years earlier. Studies of � � � � � � � � � � �� ����� � � ���������� � � � ���� the Denali Fault and the 2002 earth- � quake will provide information vital to The November 3, 2002, magnitude -

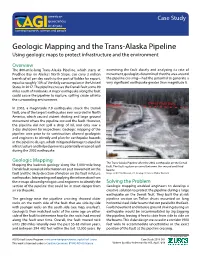

Geologic Mapping and the Trans-Alaska Pipeline Using Geologic Maps to Protect Infrastructure and the Environment

Case Study Geologic Mapping and the Trans-Alaska Pipeline Using geologic maps to protect infrastructure and the environment Overview The 800-mile-long Trans-Alaska Pipeline, which starts at examining the fault closely and analyzing its rate of Prudhoe Bay on Alaska’s North Slope, can carry 2 million movement, geologists determined that the area around barrels of oil per day south to the port of Valdez for export, the pipeline crossing—had the potential to generate a equal to roughly 10% of the daily consumption in the United very significant earthquake greater than magnitude 8. States in 2017. The pipeline crosses the Denali fault some 90 miles south of Fairbanks. A major earthquake along the fault could cause the pipeline to rupture, spilling crude oil into the surrounding environment. Denali Fault Trace In 2002, a magnitude 7.9 earthquake struck the Denali fault, one of the largest earthquakes ever recorded in North America, which caused violent shaking and large ground movement where the pipeline crossed the fault. However, the pipeline did not spill a drop of oil, and only saw a 3-day shutdown for inspections. Geologic mapping of the pipeline area prior to its construction allowed geologists and engineers to identify and plan for earthquake hazards in the pipeline design, which mitigated damage to pipeline infrastructure and helped prevent a potentially major oil spill during the 2002 earthquake. Geologic Mapping The Trans-Alaska Pipeline after the 2002 earthquake on the Denali Mapping the bedrock geology along the 1,000-mile-long fault. The fault rupture occurred between the second and third Denali fault revealed information on past movement on the beams fault and the likely direction of motion on the fault in future Image credit: Tim Dawson, U.S. -

Active and Potentially Active Faults in Or Near the Alaska Highway Corridor, Dot Lake to Tetlin Junction, Alaska

Division of Geological & Geophysical Surveys PRELIMINARY INTERPRETIVE REPORT 2010-1 ACTIVE AND POTENTIALLY ACTIVE FAULTS IN OR NEAR THE ALASKA HIGHWAY CORRIDOR, DOT LAKE TO TETLIN JUNCTION, ALASKA by Gary A. Carver, Sean P. Bemis, Diana N. Solie, Sammy R. Castonguay, and Kyle E. Obermiller September 2010 THIS REPORT HAS NOT BEEN REVIEWED FOR TECHNICAL CONTENT (EXCEPT AS NOTED IN TEXT) OR FOR CONFORMITY TO THE EDITORIAL STANDARDS OF DGGS. Released by STATE OF ALASKA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES Division of Geological & Geophysical Surveys 3354 College Rd. Fairbanks, Alaska 99709-3707 $4.00 CONTENTS Abstract ............................................................................................................................................................ 1 Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................... 1 Seismotectonic setting of the Tanana River valley region of Alaska ................................................................ 3 2008 fi eld studies .............................................................................................................................................. 5 Field and analytical methods ............................................................................................................................ 5 Dot “T” Johnson fault ....................................................................................................................................... 7 Robertson -

Magnitude Limits of Subduction Zone Earthquakes

Magnitude Limits of Subduction Zone Earthquakes Rong, Y., Jackson, D. D., Magistrale, H., Goldfinger, C. (2014). Magnitude Limits of Subduction Zone Earthquakes. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, 104(5), 2359-2377. doi:10.1785/0120130287 10.1785/0120130287 Seismological Society of America Version of Record http://cdss.library.oregonstate.edu/sa-termsofuse Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America This copy is for distribution only by the authors of the article and their institutions in accordance with the Open Access Policy of the Seismological Society of America. For more information see the publications section of the SSA website at www.seismosoc.org THE SEISMOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA 400 Evelyn Ave., Suite 201 Albany, CA 94706-1375 (510) 525-5474; FAX (510) 525-7204 www.seismosoc.org Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, Vol. 104, No. 5, pp. 2359–2377, October 2014, doi: 10.1785/0120130287 Magnitude Limits of Subduction Zone Earthquakes by Yufang Rong, David D. Jackson, Harold Magistrale, and Chris Goldfinger Abstract Maximum earthquake magnitude (mx) is a critical parameter in seismic hazard and risk analysis. However, some recent large earthquakes have shown that most of the existing methods for estimating mx are inadequate. Moreover, mx itself is ill-defined because its meaning largely depends on the context, and it usually cannot be inferred using existing data without associating it with a time interval. In this study, we use probable maximum earthquake magnitude within a time period of interest, m T m m T p , to replace x. The term p contains not only the information of magnitude m T limit but also the occurrence rate of the extreme events. -

Dynamic Response of Bridges to Near-Fault Forward Directivity Ground

Research Report Agreement 355270, Task 6 Near-Fault Ground Motions DYNAMIC RESPONSE OF BRIDGES TO NEAR-FAULT, FORWARD DIRECTIVITY GROUND MOTIONS by Adrian Rodriguez-Marek William Cofer Associate Professor Professor Civil and Environmental Engineering Department Washington State University Pullman, WA 99164 Washington State Transportation Center (TRAC) Washington State University Civil & Environmental Engineering PO Box 642910 Pullman, WA 99164-2910 Washington State Department of Transportation Technical Monitor Kim Willoughby Research Manager Materials and Construction, Bridges and Structures and Maintenance Prepared for Washington State Transportation Commission Department of Transportation and in cooperation with U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration December 2007 1. REPORT NO. 2. GOVERNMENT ACCESSION NO. 3. RECIPIENT'S CATALOG NO. WA-RD 689.1 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. REPORT DATE DYNAMIC RESPONSE OF BRIDGES TO NEAR-FAULT, December 2007 FORWARD DIRECTIVITY GROUND MOTIONS 6. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION CODE 7. AUTHOR(S) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION REPORT NO. Adrian Rodriguez-Marek and William Cofer 9. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME AND ADDRESS 10. WORK UNIT NO. Washington State Transportation Center (TRAC) Washington State University, Civil & Environmental Engineering 11. CONTRACT OR GRANT NO. PO Box 642910 WSDOT 355270, Task 6 Pullman, WA 99164-2910 12. SPONSORING AGENCY NAME AND ADDRESS 13. TYPE OF REPORT AND PERIOD COVERED Research Office Washington State Department of Transportation Research Report Transportation Building, MS 47372 Olympia, Washington 98504-7372 14. SPONSORING AGENCY CODE 15. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES This study was conducted in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration. 16. ABSTRACT Research over the last decade has shown that pulse-type earthquake ground motions that result from forward- directivity (FD) effects can result in significant damage to structures. -

Diverse Rupture Modes for Surface-Deforming Upper Plate Earthquakes in the Southern Puget Lowland of Washington State

Diverse rupture modes for surface-deforming upper plate earthquakes in the southern Puget Lowland of Washington State Alan R. Nelson1,*, Stephen F. Personius1, Brian L. Sherrod2, Harvey M. Kelsey3, Samuel Y. Johnson4, Lee-Ann Bradley1, and Ray E. Wells5 1Geologic Hazards Science Center, U.S. Geological Survey, MS 966, PO Box 25046, Denver, Colorado 80225, USA 2U.S. Geological Survey at Department of Earth and Space Sciences, University of Washington, Box 351310, Seattle, Washington 98195, USA 3Department of Geology, Humboldt State University, Arcata, California 95521, USA 4Western Coastal and Marine Geology Science Center, U.S. Geological Survey, 400 Natural Bridges Drive, Santa Cruz, California 95060, USA 5Geology, Minerals, Energy, and Geophysics Science Center, U.S. Geological Survey, 345 Middlefi eld Road, MS 973, Menlo Park, California 94025, USA ABSTRACT earthquakes. In the northeast-striking Saddle migrating forearc has deformed the Seto Inland Mountain deformation zone, along the west- Sea into a series of basins and uplifts bounded Earthquake prehistory of the southern ern limit of the Seattle and Tacoma fault by faults. One of these, the Nojima fault, pro- Puget Lowland, in the north-south com- zones, analysis of previous ages limits earth- duced the 1995 Mw6.9 Hyogoken Nanbu (Kobe) pressive regime of the migrating Cascadia quakes to 1200–310 cal yr B.P. The prehistory earthquake, which killed more than 6400 peo- forearc, refl ects diverse earthquake rupture clarifi es earthquake clustering in the central ple, destroyed the port of Kobe, and caused modes with variable recurrence. Stratigraphy Puget Lowland, but cannot resolve potential $100 billion in damage (Chang, 2010). -

By Arthur Grantz This Report Is Preliminary and Has Not Been

DEPARTMENT OF INTERIOR U. S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY STRIKE-SLIP FAULTS ITT ALASKA By Arthur Grantz OPEN-FILE REPORT This report is preliminary and has not been edited cr reviewed for conformity vich Geological Survey standards and nomenclature. CONTENTS Page Introduction- - - - - - -- 1 Structural environment of the strike-slip faults- h Description of strike- slip faults and selected linear features-- 10 Denali fault and Dcnali fault system -- 10 Farewell segment of the Denali fault " 1^ Hines Creek strand of the Denali fault - 16 McKinley strand of the Denali fault 17 Shakwak Valley segment of the Denali fault 20 Togiak-Tikchik fault-- 2U Holitna fault 25 Chilkat River fault zone-- - - - 26 Chatham Strait fault- 26 Castle Mountain fault 27 Iditarod-Nixon Fork fault - -- 28 And. ak- Thompson Creek fault- - - 30 Conjugate strike -slip faults in the Yukon delta region 30 Kaltag fault 31 Stevens Creek fault zone-- - ----- 33 Porcupine lineament-- ----- ------ -- _- - - 33 Yukon Flats discontinuity and fault--- - - --- 3^ Tintina fault zone and Tintina trench- - -- 35 Kobuk trench- - - 38 Fairweather fault-------- - -------- - -- 38 Peril Strait fault *K) Chichagof-Sitka fault and its likely southeastern extension, the Patter son Biy fault-- - ----- Ul Clarence Stra.it lincan 2nt- Age of faulting U2 Maximum apparent lateral separations- U6 Superposition of lateral slip upon pre-existing faults- ^9 Hypotheses involving the strike-slip faults 50 Relation to right-lateral slip along the Pacific Coast- - 51 Internal rotation of Alaska - 53 Bending -

Evidence for Large Holocene Earthquakes Along the Denali Fault in Southwest Yukon, Canada Authors: A

Evidence for large Holocene earthquakes along the Denali fault in southwest Yukon, Canada Authors: A. Blais-Stevens, J.J. Clague, J. Brahney, P. Lipovsky, P. Haeussler, B. Menounos Abstract The Yukon-Alaska Highway corridor in southern Yukon is subject to geohazards ranging from landslides, to floods, and earthquakes on faults in the St. Elias Mountains and Shakwak Valley. Here we discuss the late Holocene seismic history of the Denali fault, located at the eastern front of the St. Elias Mountains and one of only a few known seismically active terrestrial faults in Canada. Holocene faulting is indicated by scarps and mounds on late Pleistocene drift and by tectonically deformed Pleistocene and Holocene sediments. Previous work on trenches excavated against the fault scarp near Duke River reveals paleoseismic sediment disturbance dated to ca. 300-1200, 1200-1900, and 3000 years ago. Re-excavation of the trenches indicate a fourth event dated to 6000 years ago. The trenches are interpreted as a negative flower structure produced by extension of sediments by dextral strike-slip fault movement. Nearby Crescent Lake is ponded against the fault scarp. Sediment cores reveal four abrupt sediment and diatom changes reflecting seismic shaking at ca. 1200-1900, 1900-5900, 5900-6200, and 6500-6800 years ago. At Duke River, the fault offsets sediments, including two White River tephra layers (ca. 1900 and 1200 years old). Late Pleistocene outwash gravel and overlying Holocene aeolian sediments show in cross-section a positive flower structure indicative of postglacial contraction of the sediments by dextral strike-slip movement. Based on the number of events reflecting ~M6, we estimate the average recurrence of large earthquakes on the Yukon part of the Denali fault to be about 1300 years in the last 6500-6800 years. -

S51B-2362 Chastity Aiken1, Zhigang Peng1, David R

Tectonic Tremor Triggered along Major Strike-Slip Faults around the World S51B-2362 Chastity Aiken1, Zhigang Peng1, David R. Shelly2, David P. Hill2, Hector Gonzalez-Huizar3, Kevin Chao4, Jessica Zimmerman5, Roby Douilly6, Anne Deschamps7, Jennifer Haase8, and Eric Calais9 1Georgia Institute of Technology; 2 U.S. Geological Survey, Menlo Park; 3 University of Texas, El Paso; 4 University of Tokyo, Earthquake Research Institute; 5 Texas A & M University, Commerce; 6 Purdue University; 7 Université de Nice Sophia Antipolis; 8 Scripps Institute of Oceanography; 9 Ecole Normale Superieure Research Question Triggered Tremor Observations Triggering Potential How does triggered tremor differ on strike-slip faults around the world? Eastern Denali Fault of Yukon Territory, Canada San Andreas Fault of Parkfield, California Figure 7 (LEFT). Theoretical example of triggering Background 20130105 M7.5 Dist: 625.8 km BAZ: 163.2 deg Station: CN.HYT 20121028 M7.7 Dist: 2080.0 km BAZ: 337.7 deg Station: BK.PKD potential as a function of wave amplitude (i.e. stress), Deep tectonic tremor, which generally occurs in the lower crust beneath the 64˚ (a) 6 (a) 0.08 depth (i.e. frequency), and incidence angle on a vertical Mw7.9 North Love American BHT seismogenic zone where earthquakes occur, has been observed at several major Plate HHT 4 strike-slip fault. From Hill and Prejean (2013). CDF 0.04 Yukon Alaska Parkfield plate-bounding faults around the Pacific Rim. In order to investigate the potential 2012 Haida Gwaii 63˚ 2 M 7.5 0 BHR link between tremor and earthquake nucleation, further study of when, where, and Totschunda Fault HHR 2012 Sumatra EDF Pacific 0 Plate M 7.7 how tremor occurs is needed. -

Tectonics, Dynamics, and Seismic Hazard in the Canada–Alaska Cordillera

Tectonics, Dynamics, and Seismic Hazard in the Canada–Alaska Cordillera Stephane Mazzotti, Lucinda J. Leonard, Roy D. Hyndman, and John F. Cassidy Geological Survey of Canada, Natural Resources Canada, Sidney, British Columbia, Canada School of Earth and Ocean Science, University of Victoria, Victoria, British Columbia, Canada The North America Cordillera mobile belt has accommodated relative motion between the North America plate and various oceanic plates since the early Mesozoic. The northern half of the Cordillera (Canada–Alaska Cordillera) extends from northern Washington through western Canada and central Alaska and can be divided into four tectonic domains associated with different plate boundary interactions, variable seismicity, and seismic hazard. We present a quantitative tectonic model of the Canada–Alaska Cordillera based on an integrated set of seismicity and GPS data for these four domains: south (Cascadia subduction region), central (Queen Charlotte–Fairweather transcurrent region), north (Yakutat collision region), and Alaska (Alaska subduction region). This tectonic model is compared with a dynamic model that accounts for lithosphere strength contrasts and internal/ boundary force balance. We argue that most of the Canada–Alaska Cordillera is an orogenic float where current tectonics are mainly limited to the upper crust, which is mechanically decoupled from the lower part of the lithosphere. Variations in deformation style and magnitude across the Cordillera are mostly controlled by the balance between plate boundary forces and topography-related gravitational forces. In particular, the strong compression and gravitational forces associated with the Yakutat collision zone are the primary driver of the complex tectonics from eastern Yukon to central Alaska, resulting in crustal extrusion, translation, and deformation across a 1500 ´ 1000-km2 region. -

USGS Geologic Investigations Series I 2585, Pamphlet

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR TO ACCOMPANY MAP I–2585 U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY DIGITAL SHADED-RELIEF IMAGE OF ALASKA By J.R. Riehle1, M.D. Fleming2, B.F. Molnia3, J.H. Dover1, J.S. Kelley1, M.L. Miller1, W.J. Nokleberg4, George Plafker4, and A.B. Till1 INTRODUCTION drawn by Harrison (1970; 1:7,500,000) for The National Atlas of the United States. Recently, the State of Alaska digi- One of the most spectacular physiographic images tally produced a shaded-relief image of Alaska at 1:2,500,000 of the conterminous United States, and the first to have scale (Alaska Department of Natural Resources, 1994), us- been produced digitally, is that by Thelin and Pike (1991). ing the 1,000-m digital elevation data set referred to below. The image is remarkable for its crispness of detail and for An important difference between our image and the natural appearance of the artificial land surface. Our these previous ones is the method of reproduction: like the goal has been to produce a shaded-relief image of Alaska Thelin and Pike (1991) image, our image is a composite that has the same look and feel as the Thelin and Pike im- of halftone images that yields sharp resolution and pre- age. The Alaskan image could have been produced at the serves contrast. Indeed, the first impression of many view- same scale as its lower 48 counterpart (1:3,500,000). But ers is that the Alaskan image and the Thelin and Pike im- by insetting the Aleutian Islands into the Gulf of Alaska, age are composites of satellite-generated photographs we were able to print the Alaska map at a larger scale rather than an artificial rendering of a digital elevation (1:2,500,000) and about the same physical size as the model.