1 UNIT 4 VALIDITY, INVALIDITY and LIST of VALID SYLLOGISMS Contents 4.0 Objectives 4.1 Introduction 4.2 the Rules of Categorical

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Western Logic Formal & Informal Fallacy Types of 6 Fallacies

9/17/2021 Western Logic Formal & Informal Fallacy Types of 6 Fallacies- Examrace Examrace Western Logic Formal & Informal Fallacy Types of 6 Fallacies Get unlimited access to the best preparation resource for competitive exams : get questions, notes, tests, video lectures and more- for all subjects of your exam. Western Logic - Formal & Informal Fallacy: Types of 6 Fallacies (Philosophy) Fallacy When an argument fails to support its conclusion, that argument is termed as fallacious in nature. A fallacious argument is hence an erroneous argument. In other words, any error or mistake in an argument leads to a fallacy. So, the definition of fallacy is any argument which although seems correct but has an error committed in its reasoning. Hence, a fallacy is an error; a fallacious argument is an argument which has erroneous reasoning. In the words of Frege, the analytical philosopher, “it is a logician՚s task to identify the pitfalls in language.” Hence, logicians are concerned with the task of identifying fallacious arguments in logic which are also called as incorrect or invalid arguments. There are numerous fallacies but they are classified under two main heads; Formal Fallacies Informal Fallacies Formal Fallacies Formal fallacies are those mistakes or errors which occur in the form of the argument. In other words, formal fallacies concern themselves with the form or the structure of the argument. Formal fallacies are present when there is a structural error in a deductive argument. It is important to note that formal fallacies always occur in a deductive argument. There are of six types; Fallacy of four terms: A valid syllogism must contain three terms, each of which should be used in the same sense throughout; else it is a fallacy of four terms. -

The Validities of Pep and Some Characteristic Formulas in Modal Logic

THE VALIDITIES OF PEP AND SOME CHARACTERISTIC FORMULAS IN MODAL LOGIC Hong Zhang, Huacan He School of Computer Science, Northwestern Polytechnical University,Xi'an, Shaanxi 710032, P.R. China Abstract: In this paper, we discuss the relationships between some characteristic formulas in normal modal logic with their frames. We find that the validities of the modal formulas are conditional even though some of them are intuitively valid. Finally, we prove the validities of two formulas of Position- Exchange-Principle (PEP) proposed by papers 1 to 3 by using of modal logic and Kripke's semantics of possible worlds. Key words: Characteristic Formulas, Validity, PEP, Frame 1. INTRODUCTION Reasoning about knowledge and belief is an important issue in the research of multi-agent systems, and reasoning, which is set up from the main ideas of situational calculus, about other agents' states and actions is one of the most important directions in Al^^'^\ Papers [1-3] put forward an axiom scheme in reasoning about others(RAO) in multi-agent systems, and a rule called Position-Exchange-Principle (PEP), which is shown as following, was abstracted . C{(p^y/)^{C(p->Cy/) (Ce{5f',...,5f-}) When the length of C is at least 2, it reflects the mechanism of an agent reasoning about knowledge of others. For example, if C is replaced with Bf B^/, then it should be B':'B]'{(p^y/)-^iBf'B]'(p^Bf'B]'y/) 872 Hong Zhang, Huacan He The axiom schema plays a useful role as that of modus ponens and axiom K when simplifying proof. Though examples were demonstrated as proofs in papers [1-3], from the perspectives both in semantics and in syntax, the rule is not so compellent. -

CHAPTER XXX. of Fallacies. Section 827. After Examining the Conditions on Which Correct Thoughts Depend, It Is Expedient to Clas

CHAPTER XXX. Of Fallacies. Section 827. After examining the conditions on which correct thoughts depend, it is expedient to classify some of the most familiar forms of error. It is by the treatment of the Fallacies that logic chiefly vindicates its claim to be considered a practical rather than a speculative science. To explain and give a name to fallacies is like setting up so many sign-posts on the various turns which it is possible to take off the road of truth. Section 828. By a fallacy is meant a piece of reasoning which appears to establish a conclusion without really doing so. The term applies both to the legitimate deduction of a conclusion from false premisses and to the illegitimate deduction of a conclusion from any premisses. There are errors incidental to conception and judgement, which might well be brought under the name; but the fallacies with which we shall concern ourselves are confined to errors connected with inference. Section 829. When any inference leads to a false conclusion, the error may have arisen either in the thought itself or in the signs by which the thought is conveyed. The main sources of fallacy then are confined to two-- (1) thought, (2) language. Section 830. This is the basis of Aristotle's division of fallacies, which has not yet been superseded. Fallacies, according to him, are either in the language or outside of it. Outside of language there is no source of error but thought. For things themselves do not deceive us, but error arises owing to a misinterpretation of things by the mind. -

The Substitutional Analysis of Logical Consequence

THE SUBSTITUTIONAL ANALYSIS OF LOGICAL CONSEQUENCE Volker Halbach∗ dra version ⋅ please don’t quote ónd June óþÕä Consequentia ‘formalis’ vocatur quae in omnibus terminis valet retenta forma consimili. Vel si vis expresse loqui de vi sermonis, consequentia formalis est cui omnis propositio similis in forma quae formaretur esset bona consequentia [...] Iohannes Buridanus, Tractatus de Consequentiis (Hubien ÕÉßä, .ì, p.óóf) Zf«±§Zh± A substitutional account of logical truth and consequence is developed and defended. Roughly, a substitution instance of a sentence is dened to be the result of uniformly substituting nonlogical expressions in the sentence with expressions of the same grammatical category. In particular atomic formulae can be replaced with any formulae containing. e denition of logical truth is then as follows: A sentence is logically true i all its substitution instances are always satised. Logical consequence is dened analogously. e substitutional denition of validity is put forward as a conceptual analysis of logical validity at least for suciently rich rst-order settings. In Kreisel’s squeezing argument the formal notion of substitutional validity naturally slots in to the place of informal intuitive validity. ∗I am grateful to Beau Mount, Albert Visser, and Timothy Williamson for discussions about the themes of this paper. Õ §Z êZo±í At the origin of logic is the observation that arguments sharing certain forms never have true premisses and a false conclusion. Similarly, all sentences of certain forms are always true. Arguments and sentences of this kind are for- mally valid. From the outset logicians have been concerned with the study and systematization of these arguments, sentences and their forms. -

Propositional Logic (PDF)

Mathematics for Computer Science Proving Validity 6.042J/18.062J Instead of truth tables, The Logic of can try to prove valid formulas symbolically using Propositions axioms and deduction rules Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.1 Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.2 Proving Validity Algebra for Equivalence The text describes a for example, bunch of algebraic rules to the distributive law prove that propositional P AND (Q OR R) ≡ formulas are equivalent (P AND Q) OR (P AND R) Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.3 Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.4 1 Algebra for Equivalence Algebra for Equivalence for example, The set of rules for ≡ in DeMorgan’s law the text are complete: ≡ NOT(P AND Q) ≡ if two formulas are , these rules can prove it. NOT(P) OR NOT(Q) Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.5 Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.6 A Proof System A Proof System Another approach is to Lukasiewicz’ proof system is a start with some valid particularly elegant example of this idea. formulas (axioms) and deduce more valid formulas using proof rules Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.7 Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.8 2 A Proof System Lukasiewicz’ Proof System Lukasiewicz’ proof system is a Axioms: particularly elegant example of 1) (¬P → P) → P this idea. It covers formulas 2) P → (¬P → Q) whose only logical operators are 3) (P → Q) → ((Q → R) → (P → R)) IMPLIES (→) and NOT. The only rule: modus ponens Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.9 Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.10 Lukasiewicz’ Proof System Lukasiewicz’ Proof System Prove formulas by starting with Prove formulas by starting with axioms and repeatedly applying axioms and repeatedly applying the inference rule. -

A Validity Framework for the Use and Development of Exported Assessments

A Validity Framework for the Use and Development of Exported Assessments By María Elena Oliveri, René Lawless, and John W. Young A Validity Framework for the Use and Development of Exported Assessments María Elena Oliveri, René Lawless, and John W. Young1 1 The authors would like to acknowledge Bob Mislevy, Michael Kane, Kadriye Ercikan, and Maurice Hauck for their valuable input and expertise in reviewing various iterations of the framework as well as Priya Kannan, Don Powers, and James Carlson for their input throughout the technical review process. Copyright © 2015 Educational Testing Service. All Rights Reserved. ETS, the ETS logo, GRADUATE RECORD EXAMINATIONS, GRE, LISTENTING. LEARNING. LEADING, TOEIC, and TOEFL are registered trademarks of Educational Testing Service (ETS). EXADEP and EXAMEN DE ADMISIÓN A ESTUDIOS DE POSGRADO are trademarks of ETS. 1 Abstract In this document, we present a framework that outlines the key considerations relevant to the fair development and use of exported assessments. Exported assessments are developed in one country and are used in countries with a population that differs from the one for which the assessment was developed. Examples of these assessments include the Graduate Record Examinations® (GRE®) and el Examen de Admisión a Estudios de Posgrado™ (EXADEP™), among others. Exported assessments can be used to make inferences about performance in the exporting country or in the receiving country. To illustrate, the GRE can be administered in India and be used to predict success at a graduate school in the United States, or similarly it can be administered in India to predict success in graduate school at a graduate school in India. -

Stephen's Guide to the Logical Fallacies by Stephen Downes Is Licensed Under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 2.5 Canada License

Stephen’s Guide to the Logical Fallacies Stephen Downes This site is licensed under Creative Commons By-NC-SA Stephen's Guide to the Logical Fallacies by Stephen Downes is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 2.5 Canada License. Based on a work at www.fallacies.ca. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://www.fallacies.ca/copyrite.htm. This license also applies to full-text downloads from the site. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 3 How To Use This Guide ............................................................................................................................ 4 Fallacies of Distraction ........................................................................................................................... 44 Logical Operators............................................................................................................................... 45 Proposition ........................................................................................................................................ 46 Truth ................................................................................................................................................. 47 Conjunction ....................................................................................................................................... 48 Truth Table ....................................................................................................................................... -

Validity and Soundness

1.4 Validity and Soundness A deductive argument proves its conclusion ONLY if it is both valid and sound. Validity: An argument is valid when, IF all of it’s premises were true, then the conclusion would also HAVE to be true. In other words, a “valid” argument is one where the conclusion necessarily follows from the premises. It is IMPOSSIBLE for the conclusion to be false if the premises are true. Here’s an example of a valid argument: 1. All philosophy courses are courses that are super exciting. 2. All logic courses are philosophy courses. 3. Therefore, all logic courses are courses that are super exciting. Note #1: IF (1) and (2) WERE true, then (3) would also HAVE to be true. Note #2: Validity says nothing about whether or not any of the premises ARE true. It only says that IF they are true, then the conclusion must follow. So, validity is more about the FORM of an argument, rather than the TRUTH of an argument. So, an argument is valid if it has the proper form. An argument can have the right form, but be totally false, however. For example: 1. Daffy Duck is a duck. 2. All ducks are mammals. 3. Therefore, Daffy Duck is a mammal. The argument just given is valid. But, premise 2 as well as the conclusion are both false. Notice however that, IF the premises WERE true, then the conclusion would also have to be true. This is all that is required for validity. A valid argument need not have true premises or a true conclusion. -

Tel Aviv University the Lester & Sally Entin Faculty of Humanities the Shirley & Leslie Porter School of Cultural Studies

Tel Aviv University The Lester & Sally Entin Faculty of Humanities The Shirley & Leslie Porter School of Cultural Studies "Mischief … none knows … but herself": Intrigue and its Relation to the Drive in Late Seventeenth-Century Intrigue Drama Thesis Submitted for the Degree of "Doctor of Philosophy" by Zafra Dan Submitted to the Senate of Tel Aviv University October 2011 This work was carried out under the supervision of Professor Shirley Sharon-Zisser, Tel Aviv University and Professor Karen Alkalay-Gut, Tel Aviv University This thesis, this labor of love, would not have come into the world without the rigorous guidance, the faith and encouragement of my supervisors, Prof. Karen Alkalay-Gut and Prof. Shirley Sharon-Zisser. I am grateful to Prof. Sharon-Zisser for her Virgilian guidance into and through the less known, never to be taken for granted, labyrinths of Freudian and Lacanian thought and theory, as well as for her own ground-breaking contribution to the field of psychoanalysis through psycho-rhetoric. I am grateful to Prof. Alkalay-Gut for her insightful, inspiring yet challenging comments and questions, time and again forcing me to pause and rethink the relationship between the literary aspects of my research and psychoanalysis. I am grateful to both my supervisors for enabling me to explore a unique, newly blazed path to literary form, and rediscover thus late seventeenth-century drama. I wish to express my gratitude to Prof. Ruth Ronen for allowing me the use of the manuscript of her book Aesthetics of Anxiety before it was published. Her instructive work has been a source of enlightenment and inspiration in its own right. -

On Synthetic Undecidability in Coq, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem

On Synthetic Undecidability in Coq, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem Yannick Forster Dominik Kirst Gert Smolka Saarland University Saarland University Saarland University Saarbrücken, Germany Saarbrücken, Germany Saarbrücken, Germany [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract like decidability, enumerability, and reductions are avail- We formalise the computational undecidability of validity, able without reference to a concrete model of computation satisfiability, and provability of first-order formulas follow- such as Turing machines, general recursive functions, or ing a synthetic approach based on the computation native the λ-calculus. For instance, representing a given decision to Coq’s constructive type theory. Concretely, we consider problem by a predicate p on a type X, a function f : X ! B Tarski and Kripke semantics as well as classical and intu- with 8x: p x $ f x = tt is a decision procedure, a function itionistic natural deduction systems and provide compact д : N ! X with 8x: p x $ ¹9n: д n = xº is an enumer- many-one reductions from the Post correspondence prob- ation, and a function h : X ! Y with 8x: p x $ q ¹h xº lem (PCP). Moreover, developing a basic framework for syn- for a predicate q on a type Y is a many-one reduction from thetic computability theory in Coq, we formalise standard p to q. Working formally with concrete models instead is results concerning decidability, enumerability, and reducibil- cumbersome, given that every defined procedure needs to ity without reference to a concrete model of computation. be shown representable by a concrete entity of the model. -

Sufficient Condition for Validity of Quantum Adiabatic Theorem

Sufficient condition for validity of quantum adiabatic theorem Yong Tao † School of Economics and Business Administration, Chongqing University, Chongqing 400044, China Abstract: In this paper, we attempt to give a sufficient condition of guaranteeing the validity of the proof of the quantum adiabatic theorem. The new sufficient condition can clearly remove the inconsistency and the counterexample of the quantum adiabatic theorem pointed out by Marzlin and Sanders [Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 160408, (2004)]. Keywords: Quantum adiabatic theorem; Integral formalism; Differential formalism; Berry phase. PACS: 03.65.-w; 03.65.Ca; 03.65.Vf. 1. Introduction The quantum adiabatic theorem (QAT) [1-4] is one of the basic results in quantum physics. The role of the QAT in the study of slowly varying quantum mechanical system spans a vast array of fields and applications, such as quantum field [5], Berry phase [6], and adiabatic quantum computation [7]. However, recently, the validity of the application of the QAT had been doubted in reference [8], where Marzlin and Sanders (MS) pointed out an inconsistency. This inconsistency led to extensive discussions from physical circles [9-18]. Although there are many different viewpoints as for the inconsistency, there seems to be a general agreement that the origin is due to the insufficient conditions for the QAT. More recently, we have summarized these different viewpoints of studying the inconsistency of the QAT through the reference [19] where we have noticed that there are essentially two different types of inconsistencies of the QAT in reference [8], that is, MS inconsistency and MS counterexample. Most importantly, these two types are often confused as one [19]. -

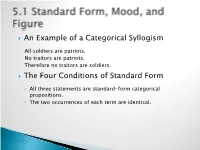

5.1 Standard Form, Mood, and Figure

An Example of a Categorical Syllogism All soldiers are patriots. No traitors are patriots. Therefore no traitors are soldiers. The Four Conditions of Standard Form ◦ All three statements are standard-form categorical propositions. ◦ The two occurrences of each term are identical. ◦ Each term is used in the same sense throughout the argument. ◦ The major premise is listed first, the minor premise second, and the conclusion last. The Mood of a Categorical Syllogism consists of the letter names that make it up. ◦ S = subject of the conclusion (minor term) ◦ P = predicate of the conclusion (minor term) ◦ M = middle term The Figure of a Categorical Syllogism Unconditional Validity Figure 1 Figure 2 Figure 3 Figure 4 AAA EAE IAI AEE EAE AEE AII AIA AII EIO OAO EIO EIO AOO EIO Conditional Validity Figure 1 Figure 2 Figure 3 Figure 4 Required Conditio n AAI AEO AEO S exists EAO EAO AAI EAO M exists EAO AAI P exists Constructing Venn Diagrams for Categorical Syllogisms: Seven “Pointers” ◦ Most intuitive and easiest-to-remember technique for testing the validity of categorical syllogisms. Testing for Validity from the Boolean Standpoint ◦ Do shading first ◦ Never enter the conclusion ◦ If the conclusion is already represented on the diagram the syllogism is valid Testing for Validity from the Aristotelian Standpoint: 1. Reduce the syllogism to its form and test from the Boolean standpoint. 2. If invalid from the Boolean standpoint, and there is a circle completely shaded except for one region, enter a circled “X” in that region and retest the form. 3. If the form is syllogistically valid and the circled “X” represents something that exists, the syllogism is valid from the Aristotelian standpoint.