Document Title

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

May CARG 2020.Pdf

ISSUE 30 – MAY 2020 ISSUE 30 – MAY ISSUE 29 – FEBRUARY 2020 Promoting positive mental health in teenagers and those who support them through the provision of mental health education, resilience strategies and early intervention What we offer Calm Harm is an Clear Fear is an app to Head Ed is a library stem4 offers mental stem4’s website is app to help young help children & young of mental health health conferences a comprehensive people manage the people manage the educational videos for students, parents, and clinically urge to self-harm symptoms of anxiety for use in schools education & health informed resource professionals www.stem4.org.uk Registered Charity No 1144506 Any individuals depicted in our images are models and used solely for illustrative purposes. We all know of young people, whether employees, family or friends, who are struggling in some way with mental health issues; at ARL, we are so very pleased to support the vital work of stem4: early intervention really can make a difference to young lives. Please help in any way that you can. ADVISER RANKINGS – CORPORATE ADVISERS RANKINGS GUIDE MAY 2020 | Q2 | ISSUE 30 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted The Corporate Advisers Rankings Guide is available to UK subscribers at £180 per in any form or by any means (including photocopying or recording) without the annum for four updated editions, including postage and packaging. A PDF version written permission of the copyright holder except in accordance with the provision is also available at £360 + VAT. of copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Barnard’s Inn, 86 Fetter Lane, London, EC4A To appear in the Rankings Guide or for subscription details, please contact us 1EN. -

Rightmove Plc, Winterhill (RMV:LN)

Rightmove Plc, Winterhill (RMV:LN) Real Estate/Real Estate Services Price: 737.40 GBX Report Date: September 22, 2021 Business Description and Key Statistics Rightmove operates as an online property portal. Co.'s segments Current YTY % Chg include The Agency, which includes resale and lettings property advertising services provided on Co.'s platforms and tenant Revenue LFY (M) 289 8.0 referencing and insurance products sold by Van Mildert Landlord EPS Diluted LFY 0.19 10.2 and Tenant Protection Limited; and The New Homes, which provides property advertising services to new home developers Market Value (M) 6,453 and housing associations on Co.'s platforms. Co.'s customers are primarily estate agents, lettings agents and new homes developers Shares Outstanding LFY (000) 875,062 advertising properties for sale and to rent in the United Kingdom. Book Value Per Share 0.05 EBITDA Margin % 75.10 Net Margin % 60.8 Website: www.rightmove.co.uk Long-Term Debt / Capital % 20.3 ICB Industry: Real Estate Dividends and Yield TTM 0.04 - 0.61% ICB Subsector: Real Estate Services Payout Ratio TTM % 34.9 Address: 2 Caldecotte Lake;Business Park;Caldecotte Lake Drive 60-Day Average Volume (000) 1,679 Milton Keynes 52-Week High & Low 746.80 - 555.80 GBR Employees: 538 Price / 52-Week High & Low 0.99 - 1.33 Price, Moving Averages & Volume 756.4 756.4 Rightmove Plc, Winterhill is currently trading at 737.40 which is 4.4% above its 50 day 730.1 730.1 moving average price of 706.13 and 15.3% above its 703.8 703.8 200 day moving average price of 639.56. -

Property Useful Links

PROPERTY - USEFUL LINKS Property - Useful Links 1300 Home Loan 1810 Malvern Road 1Casa 1st Action 1st Choice Property 1st Property Lawyers 247 Property Letting 27 Little Collins 47 Park Street 5rise 7th Heaven Properties A Place In The Sun A Plus New Homes a2dominion AACS Abacus Abbotsley Country Homes AboutProperty ABSA Access Plastics AccessIQ Accor Accord Mortgages Achieve Adair Paxton LLP Adams & Remrs Adept PROPERTY - USEFUL LINKS ADIT Brasil ADIT Nordeste Adriatic Luxury Hotels Advanced Solutions International (ASI) Affinity Sutton Affordable Millionaire Agence 107 Promenade Agency Express Ajay Ajuha Alcazaba Hills Resort Alexander Hall Alitex All Over GEO Allan Jack + Cottier Allied Pickfords Allied Surveyors AlmaVerde Amazing Retreats American Property Agent Amsprop Andalucia Country Houses Andermatt Swiss Alps Andrew and Ashwell Anglo Pacific World Movers Aphrodite Hills Apmasphere Apparent Properties Ltd Appledore Developments Ltd Archant Life Archant Life France PROPERTY - USEFUL LINKS Architectural Association School Of Architecture AREC Aristo Developers ARUP asbec Askon Estates UK Limited Aspasia Aspect International Aspinall Group Asprey Homes Asset Agents Asset Property Brokers Assetz Assoc of Home Information Pack Providers (AHIPP) Association of Residential Letting Agents (ARLA) Assoufid Aston Lloyd Astute ATHOC Atisreal Atlas International Atum Cove Australand Australian Dream Homes Awesome Villas AXA Azure Investment Property Baan Mandala Villas And Condominiums Badge Balcony Systems PROPERTY - USEFUL LINKS Ballymore -

Long-Run Ipos Performance the Case of Germany, UK and France

Long-Run IPOs Performance The case of Germany, UK and France M.Sc. in Banking and Finance October 2012 A dissertation submitted to International Hellenic University in accordance with the requirements of the degree of M.Sc. in Banking and Finance. Table of Contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................... 4 2. Terminology and Definitions in the IPOs Literature ......................................................... 6 2.1 What is an IPO, the procedure and the reasons for going Public ...................................... 6 2.2 Costs of going Public .................................................................................................... 7 3. Long-run performance Evaluation ...................................................................................... 9 4. Review of Literature ......................................................................................................... 11 4.1 Some previous studies ................................................................................................. 11 4.2 Influencing Factors according to the Literature ............................................................ 15 5. Objectives of the study and data sources ............................................................................ 17 5.1 Sample of data ............................................................................................................ 17 5.2 Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses Development ................................................ -

M Winkworth PLC (WINK:LN)

M Winkworth PLC (WINK:LN) Real Estate/Real Estate Services Price: 210.00 GBX Report Date: September 24, 2021 Business Description and Key Statistics M Winkworth is engaged in the franchising of estate agency sales, Current YTY % Chg residential lettings and property management services under the brand name Winkworth in the United Kingdom. Revenue LFY (M) 6 7.3 EPS Diluted LFY 0.10 10.2 Market Value (M) 27 Shares Outstanding LFY (000) 12,733 Book Value Per Share 0.39 EBITDA Margin % 33.90 Net Margin % 20.0 Website: www.winkworthplc.com Long-Term Debt / Capital % 0.0 ICB Industry: Real Estate Dividends and Yield TTM 0.07 - 3.43% ICB Subsector: Real Estate Services Payout Ratio TTM % 75.5 Address: 4th Floor;1 Lumley Street London 60-Day Average Volume (000) 3 GBR 52-Week High & Low 214.00 - 127.50 Employees: 44 Price / 52-Week High & Low 0.98 - 1.65 Price, Moving Averages & Volume 218.3 218.3 M Winkworth PLC is currently trading at 210.00 which is 5.8% above its 50 day moving 206.4 206.4 average price of 198.50 and 20.9% above its 200 day 194.5 194.5 moving average price of 173.63. 182.6 182.6 WINK:LN is currently 1.9% below its 52-week high price of 214.00 and is 64.7% above its 170.8 170.8 52-week low price of 127.50. Over the past 52-weeks, 158.9 158.9 WINK:LN is up 64.7% while on a calendar year-to-date basis it is up 47.4%. -

201 ,QWHUQDWLRQDO 9Aluation Handbook ,QGXVWU\ Cost of Capital

201,QWHUQDWLRQDO9aluation Handbook ,QGXVWU\ Cost of Capital Market Results Through0DUFK 2015 Duff & Phelps &RPSDQ\/LVW 1RWH 7KLV GRFXPHQW SURYLGHV D OLVW RI WKH FRPSDQLHV XVHG WR SHUIRUP WKH DQDO\VHV SXEOLVKHG LQ WKH ,QWHUQDWLRQDO 9DOXDWLRQ +DQGERRN ̰ ,QGXVWU\ &RVW RI &DSLWDO GDWD WKURXJK 0DUFK 7KHLQIRUPDWLRQ KHUHLQ LV VSHFLILF WR WKH KDUGFRYHU ,QWHUQDWLRQDO 9DOXDWLRQ +DQGERRN ̰,QGXVWU\ &RVW RI &DSLWDO GDWD WKURXJK 0DUFK DQG LV QRW DSSOLFDEOH WR DQ\ RWKHU ERRN XSGDWH RU GRFXPHQW Cover image: Duff & Phelps Cover design: Tim Harms Copyright © 2016 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey. Published simultaneously in Canada. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 646-8600, or on the Web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions. The foregoing does not preclude End-users from using the 2015 International Valuation Handbook ࣓ Industry Cost of Capital and data published therein in connection with their internal business operations. -

Broker Upgrades and Downgrades & Key Uk

Shard Capital Stockbrokers T +44 (0) 207 186 9950 rd 23 Floor, F +44 (0) 207 186 9979 20Fenchurch St, E [email protected] London, EC3M 3BY W shardcapitalstockbrokers.com BROKER UPGRADES AND DOWNGRADES & KEY UK CORPORATE SNAPSHOTS 17 January 2018 UK Broker Upgrades / Downgrades Please contact us for more information Code Company Broker Recomm. From Recomm. To Price From Price To Upgrades BLND British Land Co Plc Peel Hunt Add Add 675 700 BMY Bloomsbury Publishing Plc Peel Hunt Add Add 200 210 BYG Big Yellow Group Plc Berenberg Hold Buy 820 920 Euromoney Institutional Investor ERM Peel Hunt Buy Buy 1330 1420 Plc ETO Entertainment One Ltd Peel Hunt Hold Hold 260 300 GOCO Gocompare.com Group Plc Peel Hunt Buy Buy 125 140 RMV Rightmove Plc Peel Hunt Hold Hold 4000 4400 SAFE Safestore Holdings Plc Berenberg Buy Buy 465 550 Jefferies SPI Spire Healthcare Group Hold Buy 259 290 International UBM UBM Plc Peel Hunt Buy Buy 760 810 Zero Preference Growth Trust ZPG Peel Hunt Buy Buy 400 410 Plc/The Downgrades FERG Ferguson Plc RBC Capital Markets Outperform Sector Perform 5200 6000 HMSO Hammerson Plc Peel Hunt Hold 550 525 WMH William Hill Plc Peel Hunt Hold Reduce 290 290 https://www.shardcapitalstockbrokers.com/trading-platform/ https://www.shardcapitalstockbrokers.com/trading-platform/ https://www.shardcapitalstockbrokers.com/trading-platform/ https://www.shardcapitalstockbrokers.com/trading-platform/ https://www.shardcapitalstockbrokers.com/trading-platform/ BROKER UPGRADES AND DOWNGRADES & KEY UK CORPORATE SNAPSHOTS Code Company Broker Recomm. -

Id Epic Title Datelisted Market GB00B09Y8Y28 ATUK @UK 2005

id epic title dateListed market GB00B09Y8Y28 ATUK @UK 20051214 AIM GB00B194YY14 OPM 1PM PLC 20060802 AIM GB00B4R5B464 SPA 1SPATIAL HLDGS PLC 20101019 AIM GB0034312214 RGO 2 ERGO GROUP 20040311 AIM GB0008866310 C21 21ST CENTURY TECHNOLOGY PLC 20050415 AIM GI000A0F56M0 TTR 32RED 20050923 AIM IM00B3VVCM89 3DD 3D DIAGNOSTIC IMAGING PLC 20101122 AIM GB00B1YW4409 III 3I GROUP 19940718 UK Main Market XS0304279556 54NZ 3I GROUP 19940718 UK Main Market GB00B16PRC61 IIIP 3I GROUP 19940718 UK Main Market JE00B1RJQ972 3INW 3I INFRASTRUCTURE PLC 20070313 UK Main Market JE00B1RJLF86 3IN 3I INFRASTRUCTURE PLC 20070313 UK Main Market IM00B52P5P72 3LEG 3LEGS RESOURCES PLC 20110614 AIM GB0006640972 FOUR 4IMPRINT GROUP PLC 19531105 UK Main Market GB0008121641 SIXH 600 GROUP 20110714 AIM GI000A0F6407 888 888 HLDGS 20051004 International Main Market IE0000020408 ABBY ABBEY PLC 20041116 AIM GB00B293ZK84 ABB ABBEY PROTECTION PLC 20071129 AIM GB0000037191 ACR ABBEYCREST 19880406 UK Main Market US0028241000 ABT ABBOTT LABORATORIES 19781211 International Main Market GB00B6774699 ABC ABCAM 20051103 AIM GB0003920757 ABAA ABERDEEN ALL ASIA INVESTMENT TRUST 19981001 UK Main Market GB00B0PQ9168 AAIW ABERDEEN ASIAN INCOME FUND 20051220 UK Main Market GB00B0P6J834 AAIF ABERDEEN ASIAN INCOME FUND 20051220 UK Main Market GB0000100767 AAS ABERDEEN ASIAN SMALLER CO INV TST 19951019 UK Main Market GB0000031285 ADN ABERDEEN ASSET MANAGEMENT PLC 19910328 UK Main Market GB00B08X0660 ADNP ABERDEEN ASSET MANAGEMENT PLC 19910328 UK Main Market GB0007352502 AVC ABERDEEN DEVELOPMENT -

Online Agents

H1 2019 Results 13 December 2018 1 Today’s agenda Business Highlights Michael Bruce Financial Highlights James Davies Strategic Overview Michael Bruce Best use of tech in the digital economy award 2 Business Highlights Michael Bruce, CEO H1 2019 highlights ■ Group revenue growth up 75% ■ Year on year group sales force ■ UK up 39% ■ LPEs, AVs and Academy totalling 851 ■ Australia up 40% on a constant currency basis ■ Australia is up 24% versus H1 18 ■ US was just starting in H1 18 - in H1 19 achieved £5.9m ■ 140 LREEs in the US ■ Year on year instructions growth ■ Conversion from instruction to sale agreed ■ Group up 18% ■ UK consistent half on half at 78% ■ UK up 15% ■ Australia 77%, 83% H1 18 ■ Australia down 9% YoY ■ 91% in the US ■ Year on year average revenue per instruction (IAS 18 basis) ■ Sold and completed ■ UK up 6% ■ £5.43bn in the UK - up 17.5% ■ Australia up 6% ■ Steady in Australia at AUD 0.8bn ■ US up 121% ■ USD 337m in the US 4 Financial review James Davies, CFO Income Statement UK ■ Significant revenue increase against a tough market backdrop ■ Revenue up 39.1% under IFRS 15 (22%, IAS 18) H1 2019 H1 2018 ■ Ancillary revenue represents 44% of the total £m £m ■ ARPI1 up 6.3% to £1,209 Revenue 48.3 34.8 ■ Stabilisation of LPEs, productivity focus Cost of Sales (17.1) (14.7) ■ 74% share of hybrid space Gross Profit 31.2 20.1 Gross Margin % 64.6% 57.7% ■ Gross profit margin Adjusted administrative expenses (9.3) (7.8) ■ Headline increase of 690 bps YoY Depreciation, amortisation, share based payments and (2.7) (1.5) ■ Like -

REGISTER of SPONSORS (Tiers 2 & 5 and Sub Tiers Only)

REGISTER OF SPONSORS (Tiers 2 & 5 and Sub Tiers Only) DATE: 09-January-2017 Register of Sponsors Licensed Under the Points-based System This is a list of organisations licensed to sponsor migrants under Tiers 2 & 5 of the Points-Based System. It shows the organisation's name (in alphabetical order), the sub tier(s) they are licensed for, and their rating against each sub tier. A sponsor may be licensed under more than one tier, and may have different ratings for each tier. No. of Sponsors on Register Licensed under Tiers 2 and 5: 29,794 Organisation Name Town/City County Tier & Rating Sub Tier ?What If! Ltd London Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General Tier 2 (A rating) Intra Company Transfers (ICT) @ Home Accommodation Services Ltd London Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General Tier 5 (A rating) Creative & Sporting ]performance s p a c e [ london london Tier 5 (A rating) Creative & Sporting 01 Telecom Limited Brighton Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General 0-two Maintenance London Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General 1 Stop Print Ltd Ilford Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General 1 Tech LTD London Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General 10 Europe Limited Edinburgh Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General Tier 2 (A rating) Intra Company Transfers (ICT) 10 GROUP LTD T/A THE 10 GROUP LONDON Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General 10 Minutes With Limited London Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General Page 1 of 1952 Organisation Name Town/City County Tier & Rating Sub Tier 1000heads Ltd London Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General 1000mercis LTD London Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General 100Starlings Ltd -

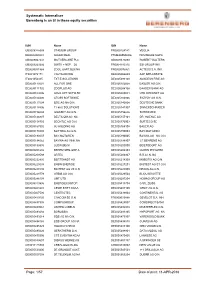

Systematic Internaliser Shares

Systematic Internaliser Berenberg is an SI in these equity securities ISIN Name ISIN Name GB0008375098 STADIUM GROUP FR0000124141 VEOLIA DE0005008007 ADLER REAL PTNBA0AM0006 NOVABASE SGPS GB0009067447 MOTHERCARE PLC GB0008475088 ROBERT WALTERS GB0009223206 SMITH + NEP. DL FR0004110310 ESI GROUP INH. DE0005031868 ZOOL.GART.BLN.NA FR0000076861 ACTEOS S.A. INH. IT0001472171 CALTAGIRONE DE0005066609 AAP IMPLANTATE IT0001454435 TXT E-SOLUTIONS DE0005093108 AMADEUS FIRE AG DE0005110001 ALL FOR ONE DE0005102008 BASLER AG O.N. DE0005111702 ZOOPLUS AG DE0005088108 BAADER BANK AG DE0005103006 ADVA OPT.NETW.SE DE0005089031 UTD.INTERNET AG DE0005104400 ATOSS SOFTWARE DE0005104806 SYZYGY AG O.N. DE0005137004 QSC AG NA O.N. DE0005140008 DEUTSCHE BANK DE0005118806 11 88 0 SOLUTIONS DE0005141907 SINNERSCHRADER DE0005156004 GIGASET AG O.N. DE0005156236 SCHWEIZER DE0005146807 DELTICOM AG NA DE0005157101 DR. HOENLE AG DE0005158703 BECHTLE AG O.N. DE0005176903 SURTECO SE DE0005167902 3U HOLDING AG DE0005168108 BAUER AG DE0005178008 SOFTING AG O.N. DE0005190003 BAY.MOTOREN DE0005190037 BAY.MOTOREN DE0005194005 BAYWA AG NA O.N. DE0005194062 BAYWA AG VINK.NA. DE0005198907 J.F.BEHRENS AG DE0005199905 LUDW.BECK DE0005200000 BEIERSDORF AG DE0005201602 BERENTZEN-GRP.A DE0005202303 QUIRIN PRIVATBK DE0005209589 ARTEC DE0005203947 B.R.A.I.N. NA DE0005232805 BERTRANDT AG DE0005218309 MOBOTIX AG O.N. DE0005220008 ENBW ENERGIE DE0005227201 BIOTEST AG ST O.N. DE0005227235 BIOTEST AG VZ O.N. DE0005220909 NEXUS AG O.N. DE0005228779 ORBIS AG O.N. DE0005229504 BIJOU BRIGITTE DE0005286108 UMT UTD DE0005297204 HOMAG GROUP AG DE0005313506 ENERGIEKONTOR DE0005313704 CARL ZEISS DE0005403901 CEWE STIFT.KGAA DE0005407100 CENIT AG O.N. DE0005407506 CENTROTEC DE0005439004 CONTINENTAL AG DE0005419105 CANCOM SE O.N. FR0000033888 GEVELOT S.A. -

Front Cover Without Sector Focus

Edison Insight Strategic perspective | Company profiles April 2016 Published by Edison Investment Research Contents Global perspectives 2 Company profiles 8 Edison dividend list 94 Results diary 96 Stock coverage 98 Prices at 22 April 2016 Published 28 April 2016 US$/£ exchange rate: 0.7010 TRY/£ exchange rate: 0.2467 €/£ exchange rate: 0.7941 HK$/£ exchange rate: 0.0904 C$/£ exchange rate: 0.5371 NOK/£ exchange rate: 0.0848 A$/£ exchange rate: 0.4936 JPY/£ exchange rate: 0.0063 NZ$/£ exchange rate: 0.4819 SG$/£ exchange rate: 0.5184 Welco me to the April edition of the Edison Insight. We now have over 400 companies under coverage, of which 172 are profiled in this edition. Healthcare companies are now covered separately in Edison Healthcare Insight. Click here to view the latest edition. The book opens with a strategy piece from Alastair George, who believes the risk of an actual Brexit is modest as polls indicate the “Remain” campaign is still on target to win the vote. However, the uncertainty surrounding Brexit may be opening up a relative valuation anomaly, as the combination of the decline in sterling and the underperformance of the UK market leaves export-led UK industrials at a significant discount to US peers. With growth expectations similar for both indices, UK investors should stay aware of the potential for M&A, despite relatively low levels of activity during 2016 to date. Separately, we remain of the view the relief rally which started in February is largely behind us. Oil prices have risen to levels more consistent with long-run marginal supply and commodity prices look to have run ahead of improvements in the economic data.