57 on the Plum Blossom (Baika)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Technical Note 30: Ability of Pacific Northwest Shrubs to Root From

TECHNICAL NOTES _____________________________________________________________________________________________ U.S. DEPT. OF AGRICULTURE NATURAL RESOURCES CONSERVATION SERVICE PORTLAND, OREGON DATE: September 2002 PLANT MATERIALS TECHNICAL NOTE NO. 30 Ability of Pacific Northwest Native Shrubs to Root from Hardwood Cuttings (with Summary of Propagation Methods for 22 Species) Dale C. Darris Conservation Agronomist Corvallis Plant Materials Center SUMMARY There is a need for additional information on how well native shrubs root from hardwood cuttings. First, nurseries are seeking to refine vegetative propagation techniques. Second, practitioners in the fields of riparian/wetland restoration and streambank stabilization are looking for species that are easy to root from unrooted dormant material that will provide cost competitive alternatives to native willows (Salix spp.) and redosier dogwood (Cornus sericea) for direct sticking of cuttings and soil bioengineering practices. The purpose of this work was to screen 15 shrubs indigenous to the Pacific Northwest USA for their ability to root from hardwood cuttings with and without a rooting compound in a greenhouse mist bench, well drained field, nursery bed, and saturated substrate (artificial pond). If a species roots easily, it has greater potential for planting as dormant cuttings, live stakes, or whips directly on a revegetation site, and may warrant further evaluation for fascines, brush mattresses, or other soil bioengineering practices. Based on the rooting ability of hardwood cuttings made from 1 (or 2) year old wood, those species with good potential include black twinberry (Lonicera involucrata), salmonberry (Rubus spectabilis), common snowberry (Symphoricarpos albus), and Pacific ninebark (Physocarpus capitatus). Coyote brush (Baccharis pilularis) and red elderberry (Sambucus racemosa) have fair potential. Indian plum (Oemlaria cerasiformis), mock orange (Philadelphus lewisii), and red flowering currant (Ribes sanguineum) may apply under limited circumstances, select uses, or ideal conditions. -

Salt-Spray Tolerant Groundcovers, Shrubs, and Trees for Eastern Long Island

Salt-spray Tolerant Groundcovers, Shrubs, and Trees for Eastern Long Island Aerial salts carried by on-shore breezes, fog, and wind can injure plants sensitive to salt deposition. The plants listed below have displayed either high or moderate tolerance to salt spray. Most species listed have displayed high tolerance ( little to no damage). Those species noted as having moderate tolerance may show signs of salt injury (tip dieback, foliar damage, reduced growth). Moderately-tolerant species should be planted in areas away from direct salt-spray exposure. Salt-spray tolerance applies to aerial deicing salts as well. The plants listed were chosen because they are relatively disease and pest resistance (unless noted), and well-suited for eastern Long Island. Perennial Groundcovers Foliage Common Name Scientific Name Habit & Comments* Deciduous Beach Pea Lathyrus maritimus native, flowering, silver-green foliage Evergreen Bearberry Arctostaphylos uva-ursi native, low-growing, soft stems Evergreen Shore Juniper Juniperus conferta spreading, dense Semi-evergreen Willowleaf Cotoneaster Cotoneaster salicifolius weeping, cascading Semi-evergreen Lily Turf Liriope muscari grass-like appearance Woody Shrubs (fifteen feet or less in height) Deciduous False Indigo-bush Amorpha fruticosa flowering shrub, prefers wet sites Deciduous Red Chokeberry Aronia arbutifolia moderate salt tolerance, native, early flowering Deciduous Black Chokecherry Aronia melanocarpa moderate salt tolerance, native, early flowering Deciduous Eastern Baccharis Baccharis halimifolia native, tolerates wet sites Deciduous Sweet Pepperbush Clethra alnifolia native, flowers late Deciduous Sweetfern Comptonia peregrina native, prefers dry sites Deciduous Creeping Cotoneaster Cotoneaster adpressus mounded, spreading Deciduous Cotoneaster Cotoneaster divaricatus upright, arching habit Deciduous Forsythia Forsythia x intermedia early spring flowering Deciduous Common Witchhazel Hamamelis virginiana native, very early flowering Deciduous Rose of Sharon Hibuscus syriacus moderately salt tolerant, flowering, mod. -

Tools of the Cabinetmaker, but Also Like the Cartwright, the Hatchet (Handbeil) and the Drawknife (Schneidemesser)

CHAPTER FIVE The Chairmaker The chairmaker bears the name in common with English chairmakers presumably because his trade is originally transplanted from England to Germany, or because several types of chairs that are made in his workshop have been common first in England. In the making of chairs, the settee (Canape), and sofa, he wields not only the plane and other tools of the cabinetmaker, but also like the cartwright, the hatchet (Handbeil) and the drawknife (Schneidemesser). I. In most regions, and especially in the German coastal cities, chairmakers make their chairs out of red beech wood, in Magdeburg out of linden wood, and in Berlin out of serviceberry wood (Elsenholz). Red beech is lacking in our area, and the cabinetmaker, who before the arrival to Berlin of chairmakers that made wooden chair frames, chose therefore serviceberry wood in place of red beech. Likewise the chairmakers, when they arrived in Berlin, found that circumstances also compelled them to build their chairs out of serviceberry wood. If the customer explicitly requires it, and will pay especially for it, they sometimes build chairs out of walnut, plum wood, pearwood, and mahogany wood, and for very distinguished and wealthy persons out of cedarwood. The chairmaker obtains the serviceberry wood partly in boards that are one to five inches thick and partly in logs. The farmer in the [town of] Mark Brandenburg brings this wood, partly in logs and also in boards, to Berlin to sell, but the strongest and best comes from Poland. If the wood has not sufficiently dried when purchased by the chairmaker it must stay some time longer and properly dry. -

Verticillium Wilt of Fraxinus Excelsior

Verticillium wilt of Fraxinus excelsior - ' . ; Jt ""* f- "" UB-^/^'IJ::J CENTRALE LANDBOUWCATALOGUS 0000 0611 8323 locjs Promotoren: Dr.Ir. R.A.A. Oldeman Hoogleraar ind e Bosteelt en Bosoecologie Dr.Ir. J. Dekker Emeritus Hoogleraar ind e Fytopathologie /OMOS-Zöl,^ Jelle A. Hiemstra Verticillium wilt of Fraxinus excelsior Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor in de landbouw- en milieuwetenschappen, op gezag van de rector magnificus, dr. C.M. Karssen, inhe t openbaar te verdedigen op dinsdag 18apri l 1995 des namiddags omvie r uur ind e aula van de Landbouwuniversiteit te Wageningen J\ ABSTRACT Hiemstra, J.A. (1995). Verticillium wilt of Fraxinus excelsior. PhD Thesis, Wageningen Agricultural University, The Netherlands, xvi + 213 pp, 40 figs., 28 tables, 4 plates with colour pictures, 327 refs., English and Dutch summaries. ISBN 90-5485-360-3 Research on ash wilt disease, a common disease of Fraxinus excelsior L. in young forest and landscape plantings in several parts of the Netherlands, is described. By means of a survey for pathogenic fungi in affected trees, inoculation and reisolation experimentsi ti sdemonstrate d thatth ediseas ei scause db y Verticilliumdahliae Kleb . Hostspecificit y andvirulenc e of aV. dahliae isolatefro m ashar ecompare d tothos e of isolatesfro m elm,mapl ean dpotato .Diseas eincidenc ean dprogress , andrecover y of infected trees are investigated through monitoring experiments in two permanent plots in seriously affected forest stands. Monitoring results are related to the results of an aerial survey for ash wilt disease in the province of Flevoland to assess the impact of the disease on ash forests. -

Price Increase: Quickship Temporarily Suspended

SURCHARGE: Effective for orders placed on and after July 15th, 2021, we will be adding a 2% surcharge to the order total, which will be reflected as a line item on your acknowledgment and invoice. The surcharge will end with the fall price increase and will not be applied to any future orders that receive the October 4th increase outlined below. PRICE INCREASE: Effective October 4th, 2021, we will implement a 5.5% price increase for all JSI products. Updated pricing will be available on e-tools following the release of the September DVD from 2020 Technologies and on the JSI website on October 4th. QUICKSHIP TEMPORARILY SUSPENDED: Effective immediately we are temporarily suspending our Quickship Program in order to deliver on our promise of on time shipments. We apologize for the inconvenience and appreciate your understanding. AMERICANA Americana Order Check List: Specify: □ 1. Model Number □ 2. Wood Species - Red Oak (RO) or Maple (M) □ 3. Wood Finish/Color □ 4. Upholstered seat style - horseshoe style available; add $20 list per chair/barstool; add $26 list per bench AMERICANA □ 5. Fabric Selection - vendor, pattern and color □ 6. Optional FRONT LEG casters - add $54 list; specify seat height NOT AVAILABLE on BARSTOOLS □ 7. Optional Trim Nails; add $101 list per chair/barstool; add $128 list per bench. Standard trim nail color is Antique Brass. Optional Black trim nails available. □ 8.Optional 1 ¾" Circle Back Cut Out - add $17 list per chair (select models) □ 9.Optional Rubber Cushion Nylon Glides - no upcharge Example: 301C RO HEN MOMENTUM VOX MYSTIC (model #) (wood species) (finish) (fabric vendor) (pattern name) (pattern color) 1. -

Principles of Archery Range Architecture a Redesign of the Yolo Bowmen South Range

Principles of Archery Range Architecture A Redesign of the Yolo Bowmen South Range Devin Caprari June 13, 2008 Principles of Archery Range Architecture: A Redesign of the Yolo Bowmen South Range A Senior Project Presented to the Faulty of the Landscape Architecture Department University of California, Davis In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of Bachelors of Science of Landscape Architecture Accepted and Approved by: ________________________________________ Faculty Committee Member, Steve Greco ________________________________________ Committee Member, Christine Alford ________________________________________ Faculty Sr. Project Advisor, Robert Thayer Devin Caprari June 13, 2008 Abstract This project is an attempt to incorporate broader environmental design principles into the existing (and limited) body of literature concerning the design of field archery ranges. I have organized these design considerations into four principles that archery clubs and land planners can utilize. Observing sensitivity to the environment, providing a layout for safe shooting, making the space comfortable, and programming inclusive spaces makes a range that serves its community well. These principles are to explain concisely how a range can be made not only to accommodate archers but also to exist harmoniously with neighboring land as well as function as a valuable community building asset. Finally, an example design treatment to the Yolo Bowmen Archery Range of Grasslands Regional Park will help to clarify the principles set forth in -

Newsletter No. 32 Let's Call This Edition

Newsletter of the Samford Valley Target Archers (ABN 63 639 289 573) www.samfordarchery.org Newsletter No. 32 February, 2017 Let’s call this edition the – 2017 Australian Open Tournament, and because a number of people liked the historical bit in the last Newsletter, what follows is the (slightly edited) text of a presentation to the Royal Historical Society of Queensland in June last year at a seminar entitled “A History of Sport in Queensland” because, in January/February “The person (or persons) who invented of 1947, the Grange Company the bow (and the arrows to go with it) of Archers came to life. This must have met considerable disbelief – “Wot – you’ll catch a squirrel with that?” archery Club, with name changes along – “How the hell do you hope to damage the way, is the oldest, continuously the Ogg clan with that thin thing?” operating, archery Club in Queensland. This is also the last Newsletter before the 2017 Australian Open Archery tournament. At this point, mid-February, we have in Nevertheless, the bow and arrow excess of 122 archers registered, with appeared in many parts of the world – two groups from Malaysia, an archer from “British Isles”, Continental countries, New Zealand, and a registrant from Asia, the Americas, Africa, Himalayan Iceland (it seems). This makes it a truly areas and Papua/New Guinea, “International Event”, so Welcome!, Hello Bro!, velkomið!, and Selamat dating! to all of our visitors. We hope you enjoy the experience, and Kuka Kuka “May your arrows fly straight!” tribesmen in Lae, 1965 To mark the Anniversary occasion, and because of the and the islands of the Torres Strait. -

Insects That Feed on Trees and Shrubs

INSECTS THAT FEED ON COLORADO TREES AND SHRUBS1 Whitney Cranshaw David Leatherman Boris Kondratieff Bulletin 506A TABLE OF CONTENTS DEFOLIATORS .................................................... 8 Leaf Feeding Caterpillars .............................................. 8 Cecropia Moth ................................................ 8 Polyphemus Moth ............................................. 9 Nevada Buck Moth ............................................. 9 Pandora Moth ............................................... 10 Io Moth .................................................... 10 Fall Webworm ............................................... 11 Tiger Moth ................................................. 12 American Dagger Moth ......................................... 13 Redhumped Caterpillar ......................................... 13 Achemon Sphinx ............................................. 14 Table 1. Common sphinx moths of Colorado .......................... 14 Douglas-fir Tussock Moth ....................................... 15 1. Whitney Cranshaw, Colorado State University Cooperative Extension etnomologist and associate professor, entomology; David Leatherman, entomologist, Colorado State Forest Service; Boris Kondratieff, associate professor, entomology. 8/93. ©Colorado State University Cooperative Extension. 1994. For more information, contact your county Cooperative Extension office. Issued in furtherance of Cooperative Extension work, Acts of May 8 and June 30, 1914, in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, -

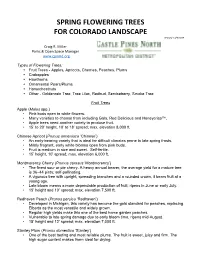

SPRING FLOWERING TREES for COLORADO LANDSCAPE Revised 12/9/2019

SPRING FLOWERING TREES FOR COLORADO LANDSCAPE Revised 12/9/2019 Craig R. Miller Parks & Open Space Manager www.cpnmd.org Types of Flowering Trees: • Fruit Trees - Apples, Apricots, Cherries, Peaches, Plums • Crabapples • Hawthorns • Ornamental Pears/Plums • Horsechestnuts • Other - Goldenrain Tree, Tree Lilac, Redbud, Serviceberry, Smoke Tree Fruit Trees Apple (Malus spp.) • Pink buds open to white flowers. • Many varieties to choose from including Gala, Red Delicious and Honeycrisp™. • Apple trees need another variety to produce fruit. • 15’ to 20’ height, 10’ to 18’ spread; max. elevation 8,000 ft. Chinese Apricot (Prunus armeniaca ‘Chinese’) • An early-bearing variety that is ideal for difficult climates prone to late spring frosts. • Mildly fragrant, early white blooms open from pink buds. • Fruit is medium in size and sweet. Self-fertile. • 15’ height, 10’ spread; max. elevation 6,000 ft. Montmorency Cherry (Prunus cerasus ‘Montmorency’) • The finest sour or pie cherry. A heavy annual bearer, the average yield for a mature tree is 36–44 pints; self-pollinating. • A vigorous tree with upright, spreading branches and a rounded crown, it bears fruit at a young age. • Late bloom means a more dependable production of fruit; ripens in June or early July. • 15’ height and 10’ spread; max. elevation 7,500 ft. Redhaven Peach (Prunus persica ‘Redhaven’) • Developed in Michigan, this variety has become the gold standard for peaches, replacing Elberta as the most versatile and widely grown. • Regular high yields make this one of the best home garden peaches. • Vulnerable to late spring damage due to early bloom time, ripens mid-August. • 15’ height and 12’ spread; max. -

Apples: Akane Amere De Berthcourt (Cider) Ashmead Kernal Belle De

Christianson’s Fruit Tree List 2019 Apples: Red Jonagold Akane Scarlet Sentinal Amere de Berthcourt (cider) Scarlet Surprise (red flesh) Ashmead Kernal Spartan Belle De Bogkoop (M-111) Whitney (crab) Beni Shogun Fuji Williams Pride Braeburn Yellow Transparent Brown Snout (cider) Centennial (crab) All semi-dwarf 106 rootstock (unless Chehalis otherwise noted). Semi-dwarf Cosmic Crisp rootstock (MM106) grows between Cortland (4-year old) 14’-18’ tall and wide. Space 20’ Cox’s Orange Pippen apart. Dwarf rootstock (M26), Early Pink Lady grows 12-16’ tall. Mini-dwarf (M27) Enterprise grows 6-8’ tall. Era (red flesh) Fameuse (M-111) European Pears: Firecracker (red flesh, 3-year old) Gold Sentinal Anjou Granvenstein Bartlett Gravenstein (dwarf) Bose Graventstein (mini-dwarf) Comice Honeycrisp Conference Honeycrisp (mini-dwarf) Flemish Beauty Hudson’s Golden Gem (M-111) Harrow Delight Jonagold Orcas Jonagold (dwarf) Red Bartlett Jonagold (mini-dwarf) Rescue Karmijn (4-year old) Seckel King Ubileen King (dwarf) Kingston Black (cider) Eurasian Pears: Liberty Liberty (mini-dwarf, 3-year old)) Maxie Melrose Reddy Robin Melrose (mini-dwarf) Mountain Rose (red flesh, 3-year old) Asian Pears: Northpole Pink Pearl Chojuro Red Gravenstien (dwarf) Hosui Nijisseiki Christianson’s Fruit Tree List 2019 Shinglo European Plums: Shinko Shinseiki Blue Damson Brooks All Semi-dwarf, Old Home x Green Gage Farmingdale 333 rootstock, grows Imperial Epeneuse 15-16’ tall. Italian Italian (dwarf St. Julien A) Fruiting Quince: Nadia (plum x cherry) Seneca Aromathaya Stanley Orange (3-year old) Yellow Egg Pineapple (3-year old) Smyra (3-year old) All Semi-dwarf Marianna rootstock, grows 14-16’ tall and wide. -

Plums, Nectarines, Apricots, Cherries, Almonds and Prunus Hybrids

E-612 2-13 Texas Fruit and Nut Production lums, Nectarines, Apricots Cherries, Almonds and Prunus hybrids Larry Stein, Jim Kamas, and Monte Nesbitt Extension Fruit Specialists, The Texas A&M University System s closely related members of the rose family, plums and apricots typically require similar management. Both fruits have performed Amuch better in Texas than nectarines, almonds, sweet cherries, and Prunus hybrids because they are less susceptible to disease, varmints, and crop loss due to premature blooming. Plums The plum tree has white flowers and sets fruit on buds from previous season’s growth (Fig. 1). Usually Figure 1. A plum orchard in full bloom. the fruit has a dusty white coating or wax bloom that is easily rubbed off (Fig. 2). Plums can be sweet to tart; the skin is typically quite tart. The two main species used in the United States are the European plum, Prunus domestica, and the Japanese plum, Prunus salycina. The European plum includes varieties such as ‘Stanley’, which is grown for fresh fruit and often dried for use as prunes. These varieties have produced poorly in Texas because they require cold climates and are susceptible to fungal diseases such as brown rot. The varieties adapted to Texas are usually hybrids Figure 2. The dusty white coating associated with between P. domestica and P. salycina and are known plums is known as wax bloom. 1 Figure 4. Eating a ripe, juicy Figure 5. ‘Bruce’ plums. ‘Methley’ plum right off the tree. as Japanese or Japanese hybrid varieties. Most plum varieties are not self-fruitful. -

Oak Willow Cherry, Plum Blueberry, Cranberry

Top 10 OAK Family: Fagaceae Genus: Quercus The mighty oak supports 534 species of butterflies/moths, and its acorns feed deer, 1 turkeys, bear, squirrels, even wood ducks. There are 80 oak species in North America. WILLOW BLUEBERRY, Family: Salicaceae CRANBERRY 2 Genus: Salix Family: Ericaceae 7 Genus: Vaccinium With 97 willow species in north america, there are lots to choose Underused in ornamental plant- from. they support some of the ings, they host butterflies/moths showiest butterflies, e.g., viceroys. and nourish birds and mammals. CHERRY, PLUM MAPLE Family: Rosaceae Family: Aceraceae 3 Genus: Prunus Genus: Acer 8 native plums and wild cherries, since the demise of the american including black cherry, choke- chestnut, maples have expanded cherry, and pin cherry, are excel- their role in the forest. they sup- lent sources of food for wildlife. port 285 lepidoptera species. BIRCH ELM Family: Betulaceae Family: Ulmaceae 4 Genus: Betula Genus: Ulmus 9 birches support hundreds of intense breeding programs have butterfly/moth species, plus produced disease-resistant ameri- they produce seeds and flower can elms. a few caterpillars eat buds that feed a variety of birds, nothing else and look like its leaves. from songbirds to turkeys. POPLAR PINE Family: Salicaceae Family: Pinaceae 5 Genus: Populus Genus: Pinus 10 lepidoptera love these fast-growing despite their resins and terpenes, trees. they harbor 7 giant silk moth, pine needles are a favorite food 7 sphinx moth, 77 noctuid (noctur- of 203 species of butterflies/ nal moth) and 10 butterfly species. moths in eastern forests. CRABAPPLE This hornworm is the larva of the hummingbird sphinx Family: Rosaceae moth.