Teacher's Resource Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Danward.Ch [email protected] Dan Ward – 100 Cover Songs Facebook.Com/Danwardsongwriter

danward.ch [email protected] Dan Ward – 100 Cover Songs facebook.com/danwardsongwriter # Artist Song # Artist Song # Artist Song 1. Avicii / Aloe Blacc Wake Me Up 35. Jack Johnson Good People 69. Steelers Wheel Stuck in the Middle with You 2. Babybird You're Gorgeous 36. Jack Johnson Taylor 70. The 5, 6, 7, 8s Woo Hoo 3. Bill Withers Ain't No Sunshine 37. Jake Bugg Lightning Bolt 71. The Beatles Twist n Shout 4. Bob Dylan / Jimi Hendrix All Along the Watchtower 38. Jason Mraz I'm Yours 72. The Black Keys Lonely Boy 5. Bob Marley Three Little Birds 39. John Lennon Imagine 73. The Clash Should I Stay or Should I Go? 6. Bob Marley Redemption Song 40. Johnny Cash Folsom Prison Blues 74. The Cure Friday I'm in Love 7. Bob Marley Small Axe 41. Johnny Cash Hurt 75. The Doors Love Me Two Times 8. Bobby Helms Jingle Bell Rock 42. Johnny Cash Man in Black 76. The Doors People Are Strange 9. Brenda Lee Rocking Around the Xmas Tree 43. Johnny Cash Ring of Fire 77. The Eels Mr E's Beautiful Blues 10. Bruce Springstein Santa Claus is Coming To Town 44. Kings of Leon Use Somebody 78. The Jam That's Entertainment 11. Buddy Rich The Beat Goes On 45. Led Zeppelin Stairway To Heaven 79. The Highwaymen The Highwayman 12. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 46. Linkin Park Castle of Glass 80. The Killers Mr Brightside 13. Dean Martin Let It Snow 47. Lou Reed Satellite of Love 81. -

Tuesday June 18 : New York

Written by: Rob van Oosten Hondsdrafstraat 1 1441 PB Purmerend The Netherlands E – Mail : [email protected] © R. van Oosten 1 Introduction. When I was in training to become a teacher ( In the Netherlands that’s the Teachers Training College ) there was an advertisement for Counselors in the United States. Together with my friend Raymond we applied and after a sollicitation talk and the approval of our college we were allowed to go . Working in a summer camp for about 9 weeks and a round trip for 4 weeks. At that time I was 19 years old and did not spend such a long time away from home. I went to several European countries with my parents and was on a holiday in France with another friend ( for a month) the year before. My parents and girl friend ( Gerda to whom I ‘m married ) did not really like the idea but did not stop me. The experience of working in Camp Hurley is one I will never forget. It was a long and hard summer and I lost beside the sweat also a lot of weight. It was a period in which I foumd out that working together is not as easy as it seems to be, working with children can be difficult and it means that you have to invest in yourself and others. So to work in Camp Hurley with these difficult kids has been fundamental in my life. Every year, maybe every month I think about that period and I tried to go back there 6 years ago. -

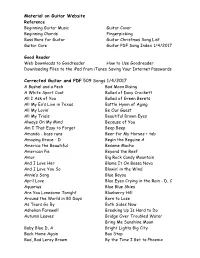

1Guitar PDF Songs Index

Material on Guitar Website Reference Beginning Guitar Music Guitar Cover Beginning Chords Fingerpicking Bass Runs for Guitar Guitar Christmas Song List Guitar Care Guitar PDF Song Index 1/4/2017 Good Reader Web Downloads to Goodreader How to Use Goodreader Downloading Files to the iPad from iTunes Saving Your Internet Passwords Corrected Guitar and PDF 509 Songs 1/4/2017 A Bushel and a Peck Bad Moon Rising A White Sport Coat Ballad of Davy Crockett All I Ask of You Ballad of Green Berets All My Ex’s Live in Texas Battle Hymn of Aging All My Lovin’ Be Our Guest All My Trials Beautiful Brown Eyes Always On My Mind Because of You Am I That Easy to Forget Beep Beep Amanda - bass runs Beer for My Horses + tab Amazing Grace - D Begin the Beguine A America the Beautiful Besame Mucho American Pie Beyond the Reef Amor Big Rock Candy Mountain And I Love Her Blame It On Bossa Nova And I Love You So Blowin’ in the Wind Annie’s Song Blue Bayou April Love Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain - D, C Aquarius Blue Blue Skies Are You Lonesome Tonight Blueberry Hill Around the World in 80 Days Born to Lose As Tears Go By Both Sides Now Ashokan Farewell Breaking Up Is Hard to Do Autumn Leaves Bridge Over Troubled Water Bring Me Sunshine Moon Baby Blue D, A Bright Lights Big City Back Home Again Bus Stop Bad, Bad Leroy Brown By the Time I Get to Phoenix Bye Bye Love Dream A Little Dream of Me Edelweiss Cab Driver Eight Days A Week Can’t Help Falling El Condor Pasa + tab Can’t Smile Without You Elvira D, C, A Careless Love Enjoy Yourself Charade Eres Tu Chinese Happy -

In Defense of Rap Music: Not Just Beats, Rhymes, Sex, and Violence

In Defense of Rap Music: Not Just Beats, Rhymes, Sex, and Violence THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Crystal Joesell Radford, BA Graduate Program in Education The Ohio State University 2011 Thesis Committee: Professor Beverly Gordon, Advisor Professor Adrienne Dixson Copyrighted by Crystal Joesell Radford 2011 Abstract This study critically analyzes rap through an interdisciplinary framework. The study explains rap‟s socio-cultural history and it examines the multi-generational, classed, racialized, and gendered identities in rap. Rap music grew out of hip-hop culture, which has – in part – earned it a garnering of criticism of being too “violent,” “sexist,” and “noisy.” This criticism became especially pronounced with the emergence of the rap subgenre dubbed “gangsta rap” in the 1990s, which is particularly known for its sexist and violent content. Rap music, which captures the spirit of hip-hop culture, evolved in American inner cities in the early 1970s in the South Bronx at the wake of the Civil Rights, Black Nationalist, and Women‟s Liberation movements during a new technological revolution. During the 1970s and 80s, a series of sociopolitical conscious raps were launched, as young people of color found a cathartic means of expression by which to describe the conditions of the inner-city – a space largely constructed by those in power. Rap thrived under poverty, police repression, social policy, class, and gender relations (Baker, 1993; Boyd, 1997; Keyes, 2000, 2002; Perkins, 1996; Potter, 1995; Rose, 1994, 2008; Watkins, 1998). -

WEB KARAOKE EN-NL.Xlsx

ARTIEST TITEL 10CC DREADLOCK HOLIDAY 2 LIVE CREW DOO WAH DIDDY 2 UNLIMITED NO LIMIT 3 DOORS DOWN KRYPTONITE 4 NON BLONDES WHAT´S UP A HA TAKE ON ME ABBA DANCING QUEEN ABBA DOES YOUR MOTHER KNOW ABBA GIMMIE GIMMIE GIMMIE ABBA MAMMA MIA ACE OF BASE DON´T TURN AROUND ADAM & THE ANTS STAND AND DELIVER ADAM FAITH WHAT DO YOU WANT ADELE CHASING PAVEMENTS ADELE ROLLING IN THE DEEP AEROSMITH LOVE IN AN ELEVATOR AEROSMITH WALK THIS WAY ALANAH MILES BLACK VELVET ALANIS MORISSETTE HAND IN MY POCKET ALANIS MORISSETTE IRONIC ALANIS MORISSETTE YOU OUGHTA KNOW ALBERT HAMMOND FREE ELECTRIC BAND ALEXIS JORDAN HAPPINESS ALICIA BRIDGES I LOVE THE NIGHTLIFE (DISCO ROUND) ALIEN ANT FARM SMOOTH CRIMINAL ALL NIGHT LONG LIONEL RICHIE ALL RIGHT NOW FREE ALVIN STARDUST PRETEND AMERICAN PIE DON MCLEAN AMY MCDONALD MR ROCK & ROLL AMY MCDONALD THIS IS THE LIFE AMY STEWART KNOCK ON WOOD AMY WINEHOUSE VALERIE AMY WINEHOUSE YOU KNOW I´M NO GOOD ANASTACIA LEFT OUTSIDE ALONE ANIMALS DON´T LET ME BE MISUNDERSTOOD ANIMALS WE GOTTA GET OUT OF THIS PLACE ANITA WARD RING MY BELL ANOUK GIRL ANOUK GOOD GOD ANOUK NOBODY´S WIFE ANOUK ONE WORD AQUA BARBIE GIRL ARETHA FRANKLIN R-E-S-P-E-C-T ARETHA FRANKLIN THINK ARTHUR CONLEY SWEET SOUL MUSIC ASWAD DON´T TURN AROUND ATC AROUND THE WORLD (LA LA LA LA LA) ATOMIC KITTEN THE TIDE IS HIGH ARTIEST TITEL ATOMIC KITTEN WHOLE AGAIN AVRIL LAVIGNE COMPLICATED AVRIL LAVIGNE SK8TER BOY B B KING & ERIC CLAPTON RIDING WITH THE KING B-52´S LOVE SHACK BACCARA YES SIR I CAN BOOGIE BACHMAN TURNER OVERDRIVE YOU AIN´T SEEN NOTHING YET BACKSTREET BOYS -

Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five

Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five To download an editable PowerPoint, visit edu.rockhall.com Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five: Fast Facts • Formed in 1976 in the South Bronx, New York; broke up by 1986 • Members: DJ Grandmaster Flash and rappers Melle Mel, Kidd Creole, Mr. Ness/Scorpio, Cowboy, and Rahiem • Recorded at Sugar Hill Records, the first hip-hop record label • Grandmaster Flash revolutionized the use of turntables in hip-hop by developing techniques such as “scratching” and “punch phrasing.” • First hip-hop group to be inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame (2007) Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five: Important Bronx Locations New Jersey ▪ South Bronx (Bronx), New York New York City Recognized birthplace of hip-hop music and culture; Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five’s home neighborhood Queens ▪ Harlem (Manhattan), New York Recorded with Enjoy Records until 1980 ▪ Englewood, New Jersey Brooklyn Recorded with Sugar Hill Records (the first hip-hop record label) from 1980 to 1984 Staten Island Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five: Two Essential Songs “Superappin’” “The Message” • Released in 1982 on Sugar Hill • Released in 1979 on Records Enjoy Records • Features Melle Mel and guest • One of the earliest rapper Duke Bootee rap records ever sold • Conveys the difficulties of life in the • Mimics the “hip-hop South Bronx, with lyrics about jam,” a live performance poverty, violence, and with audience interaction drug use • Hip-hop was originally heard • Early example of at lengthy dance parties, so a “conscious rap,” where 12-minute song seemed very lyrics convey a serious, short! often political message Grandmaster Flash’s Turntable Innovations • Grandmaster Flash developed turntable techniques and special effects that gave DJs more musical freedom. -

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

AXS TV Canada Schedule for Mon. November 23, 2020 to Sun

AXS TV Canada Schedule for Mon. November 23, 2020 to Sun. November 29, 2020 Monday November 23, 2020 2:30 PM ET / 11:30 AM PT 6:00 AM ET / 3:00 AM PT Rock & Roll Road Trip With Sammy Hagar Tom Green Live Rock & Roll Beach Party - It’s a music festival Sammy-style. Join the Red Rocker for the first an- Marlon Wayans - Comrades in comedy convene Tom trades laughs with Marlon Wayans and nual High Tide Beach Party & Car Show. Vince Neil, Kevin Cronin, Eddie Trunk, Tre Cool, and Eddie Harland Williams. An American comedy dynasty is represented when actor/comedian/writer Money meet up with Sammy at the beach along with 14,000 of their closest friends. Marlon Wayans grabs a seat across from Tom. And he always brings it, whether plying his trade in sit-coms, feature films, or a sketch and variety series like In Living Color. The sardonic Williams, 3:00 PM ET / 12:00 PM PT an accomplished stand-up with a string of appearances on late-night TV, is currently starring in Live From Daryl’s House the sit-com Package Deal. Rob Thomas - Multi Grammy winner Rob Thomas teams up with Daryl Hall on hit songs like “3 AM” and “She’s Gone” on this episode of Live From Daryl’s House. 7:00 AM ET / 4:00 AM PT The Very VERY Best of the 70s 4:00 PM ET / 1:00 PM PT Amazing Toys - From silly to groundbreaking, these play things filled everyone with hours of fun. -

![[E:] 09 a Second Face.Mp3=2129222 ACDC Whole Lotta Rosie (Rare Live](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7220/e-09-a-second-face-mp3-2129222-acdc-whole-lotta-rosie-rare-live-217220.webp)

[E:] 09 a Second Face.Mp3=2129222 ACDC Whole Lotta Rosie (Rare Live

mTad [E:] 09 A Second face.mp3=2129222 ACDC Whole Lotta Rosie (rare live Bon Scott).mp3=4874280 Damnation of Adam Blessing - Second Damnation - 05 - Back to the River.mp3=5113856 Eddie Van Halen - Eruption (live, rare).mp3=2748544 metallica - CreepingDeath (live).mp3=4129152 [E:\1959 - Miles Davis - Kind Of Blue] 01 So What.mp3=13560814 02 Freddie Freeloader.mp3=14138851 03 Blue In Green.mp3=8102685 04 All Blues.mp3=16674264 05 Flamenco Sketches.mp3=13561792 06 Flamenco Sketches (Alternate Take).mp3=13707024 B000002ADT.01.LZZZZZZZ.jpg=19294 Thumbs.db=5632 [E:\1965 - The Yardbirds & Sonny Boy Williamson] 01 - Bye Bye Bird.mp3=2689034 02 - Mister Downchild.mp3=4091914 03 - 23 Hours Too Long.mp3=5113866 04 - Out Of The Water Coast.mp3=3123210 05 - Baby Don't Worry.mp3=4472842 06 - Pontiac Blues.mp3=3864586 07 - Take It Easy Baby (Ver 1).mp3=4153354 08 - I Don't Care No More.mp3=3166218 09 - Do The Weston.mp3=4065290 10 - The River Rhine.mp3=5095434 11 - A Lost Care.mp3=2060298 12 - Western Arizona.mp3=2924554 13 - Take It Easy Baby (Ver 2).mp3=5455882 14 - Slow Walk.mp3=1058826 15 - Highway 69.mp3=3102730 albumart_large.jpg=11186 [E:\1971 Nazareth] 01 - Witchdoctor Woman.mp3=3994574 02 - Dear John.mp3=3659789 03 - Empty Arms, Empty Heart.mp3=3137758 04 - I Had A Dream.mp3=3255194 05 - Red Light Lady.mp3=5769636 06 - Fat Man.mp3=3292392 07 - Country Girl.mp3=3933959 08 - Morning Dew.mp3=6829163 09 - The King Is Dead.mp3=4603112 10 - Friends (B-side).mp3=3289466 11 - Spinning Top (alternate edit).mp3=2700144 12 - Dear John (alternate edit).mp3=2628673 -

The Beverly Hillbillies: a Comedy in Three Acts; 9780871294111; 1968; Dramatic Publishing, 1968

Paul Henning; The Beverly Hillbillies: A Comedy in Three Acts; 9780871294111; 1968; Dramatic Publishing, 1968 The Beverly Hillbillies is an American situation comedy originally broadcast for nine seasons on CBS from 1962 to 1971, starring Buddy Ebsen, Irene Ryan, Donna Douglas, and Max Baer, Jr. The series is about a poor backwoods family transplanted to Beverly Hills, California, after striking oil on their land. A Filmways production created by writer Paul Henning, it is the first in a genre of "fish out of water" themed television shows, and was followed by other Henning-inspired country-cousin series on CBS. In 1963, Henning introduced Petticoat Junction, and in 1965 he reversed the rags The Beverly Hillbillies - Season 3 : A nouveau riche hillbilly family moves to Beverly Hills and shakes up the privileged society with their hayseed ways. The Beverly Hillbillies - Season 3 English Sub | Fmovies. Loading Turn off light Report. Loading ads You can also control the player by using these shortcuts Enter/Space M 0-9 F. Scroll down and click to choose episode/server you want to watch. - We apologize to all users; due to technical issues, several links on the website are not working at the moments, and re - work at some hours late. Watch The Beverly Hillbillies 3 Online. the beverly hillbillies 3 full movie with English subtitle. Stars: Buddy Ebsen, Donna Douglas, Raymond Bailey, Irene Ryan, Max Baer Jr, Nancy Kulp. "The Beverly Hillbillies" is a classic American comedy series that originally aired for nine seasons from 1962 to 1971 and was the first television series to feature a "fish out of water" genre. -

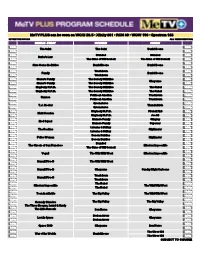

Ldim4-1620832776-Metv Plus 2Q21.Pdf

Daniel Boone MeTV PLUS can be seen on WCIU 26.5 • Xfinity 361 • RCN 30 • WOW 196 • Spectrum 188 EFFECTIVE 5/15/21 ALL TIMES CENTRAL MONDAY - FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY 5:00a 5:00a The Saint The Saint Daniel Boone 5:30a 5:30a 6:00a Branded Branded 6:00a Burke's Law 6:30a The Guns of Will Sonnett The Guns of Will Sonnett 6:30a 7:00a 7:00a Here Come the Brides Daniel Boone Daniel Boone 7:30a 7:30a 8:00a Trackdown 8:00a Family Daniel Boone 8:30a Trackdown 8:30a 9:00a Mama's Family The Beverly Hillbillies 9:00a Cheyenne 9:30a Mama's Family The Beverly Hillbillies 9:30a 10:00a Mayberry R.F.D. The Beverly Hillbillies The Rebel 10:00a 10:30a Mayberry R.F.D. The Beverly Hillbillies The Rebel 10:30a 11:00a Petticoat Junction Trackdown 11:00a Cannon 11:30a Petticoat Junction Trackdown 11:30a 12:00p Green Acres 12:00p T.J. Hooker Thunderbirds 12:30p Green Acres 12:30p 1:00p Mayberry R.F.D. Fireball XL5 1:00p Matt Houston 1:30p Mayberry R.F.D. Joe 90 1:30p 2:00p Mama's Family Stingray 2:00p Mod Squad 2:30p Mama's Family Supercar 2:30p 3:00p Laverne & Shirley 3:00p The Rookies Highlander 3:30p Laverne & Shirley 3:30p 4:00p Bosom Buddies 4:00p Police Woman Highlander 4:30p Bosom Buddies 4:30p 5:00p Branded 5:00p The Streets of San Francisco Mission: Impossible 5:30p The Guns of Will Sonnett 5:30p 6:00p 6:00p Vega$ The Wild Wild West Mission: Impossible 6:30p 6:30p 7:00p 7:00p Hawaii Five-O The Wild Wild West 7:30p 7:30p 8:00p 8:00p Hawaii Five-O Cheyenne Sunday Night Cartoons 8:30p 8:30p 9:00p Trackdown 9:00p Hawaii Five-O 9:30p Trackdown 9:30p 10:00p The -

FOXY LADY As Recorded by Jimi Hendrix (From the 1967 Album ARE YOU EXPERIENCED?) Transcribed by Roadkill Words and Music by Jimi Hendrix

FOXY LADY As recorded by Jimi Hendrix (From the 1967 Album ARE YOU EXPERIENCED?) Transcribed by Roadkill Words and Music by Jimi Hendrix A Intro Moderate Rock = 100 1 P 4 UU W gV V } V V I 4 gV V Gtr I gVf V [1/2[[[[[[[[[[[[[[[[[[[[[[[[[[[[[[[[[[[[[[[[[[[[[[[ (0) 5 x 5 5 T (10)M 10 5 x 5 5 10 ((10)) 11 A 4 4 B 2 2 sl. 4 gV V gV j V V j V j V I Gtr II mf T 14[[ 14[[[[[ 14[[[[[ A 14 14 14 14 B sl. } eV V V V V V V V } eV I V V V R V V gV V V V V gV V V V P gV gV V fV V gV GtgVr I V V gV V gV V x 5 5 5 5 5 x T x 4 4 4 5 5 5 5 5 x 4 4 4 4 4 4 A 4 4 4 4 4 4 2 4 4 4 B 0 2 2 2 2 4 7 3 4 2 2 2 2 2 2 H sl. 1967 Six Continents Music Publishing, Inc. Generated using the Power Tab Editor by Brad Larsen. http://powertab.guitarnetwork.org PDF created with FinePrint pdfFactory trial version www.pdffactory.com FOXY LADY - Jimi Hendrix Page 2 of 10 B 1st Verse 7 V V V V eV V V V V V I gV V V V gV V V V V gV V V V V GtgVr I V gV V 1/2 gV V 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 T 5 5 5 5 4 (4)M 5 5 5 4 4 (4) A 4 4 4 4 4 4 (4) O 4 4 2 B 0 2 O 2 2 2 2 O 2 2 gV gV V j V j V V j V V j V I Gtr II T 14[[[[[[ [[ 14[[ 14 [[[[[[ A 14 14 14 14 14 14 B 10 V } V V gVV VV V } eV V V I } V V V gV V fV gV gV V gV V V V V gV V gV V gV V V 1/2 5 x 5 5 2 2 5 x T 5 x 5 5 5 5 5 x 4 M 4 4 4 A 4 4 4 4 O 4 B 4 2 3 4 0 2 O 2 5 2 2 2 2 O gV gV V V } V V V P gV V V I j gV V u k j j z j tr T 14[[[[[ [ 14[[ 14 [[[[[ 14 14 (16) 14 14 14 14 A x 14 16 14 B 16 14 sl.