The State, Popular Mobilisation and Gold Mining in Mongolia ECONOMIC EXPOSURES in ASIA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Rivers of Mongolia

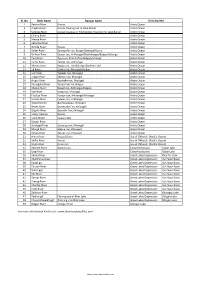

Sl. No River Name Russian Name Draining Into 1 Yenisei River Russia Arctic Ocean 2 Angara River Russia, flowing out of Lake Baikal Arctic Ocean 3 Selenge River Сэлэнгэ мөрөн in Sükhbaatar, flowing into Lake Baikal Arctic Ocean 4 Chikoy River Arctic Ocean 5 Menza River Arctic Ocean 6 Katantsa River Arctic Ocean 7 Dzhida River Russia Arctic Ocean 8 Zelter River Зэлтэрийн гол, Bulgan/Selenge/Russia Arctic Ocean 9 Orkhon River Орхон гол, Arkhangai/Övörkhangai/Bulgan/Selenge Arctic Ocean 10 Tuul River Туул гол, Khentii/Töv/Bulgan/Selenge Arctic Ocean 11 Tamir River Тамир гол, Arkhangai Arctic Ocean 12 Kharaa River Хараа гол, Töv/Selenge/Darkhan-Uul Arctic Ocean 13 Eg River Эгийн гол, Khövsgöl/Bulgan Arctic Ocean 14 Üür River Үүрийн гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 15 Uilgan River Уйлган гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 16 Arigiin River Аригийн гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 17 Tarvagatai River Тарвагтай гол, Bulgan Arctic Ocean 18 Khanui River Хануй гол, Arkhangai/Bulgan Arctic Ocean 19 Ider River Идэр гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 20 Chuluut River Чулуут гол, Arkhangai/Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 21 Suman River Суман гол, Arkhangai Arctic Ocean 22 Delgermörön Дэлгэрмөрөн, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 23 Beltes River Бэлтэсийн Гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 24 Bügsiin River Бүгсийн Гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 25 Lesser Yenisei Russia Arctic Ocean 26 Kyzyl-Khem Кызыл-Хем Arctic Ocean 27 Büsein River Arctic Ocean 28 Shishged River Шишгэд гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 29 Sharga River Шарга гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 30 Tengis River Тэнгис гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 31 Amur River Russia/China -

Committee on the Human Rights of Parliamentarians

138th IPU ASSEMBLY AND RELATED MEETINGS Geneva, 24 – 28.03.2018 Governing Council CL/202/11(b)-R.2 Item 11(b) Geneva, 28 March 2018 Committee on the Human Rights of Parliamentarians Report on the mission to Mongolia 11 - 13 September 2017 MNG01 - Zorig Sanjasuuren Table of contents A. Origin and conduct of the mission ................................................................ 4 B. Outline of the case and the IPU follow up action ........................................... 5 C. Information gathered during the mission ...................................................... 7 D. Findings and recommendations further to the mission ................................ 15 E. Recent developments ................................................................................... 16 F. Observations provided by the authorities ..................................................... 17 G. Observations provided the complainant ....................................................... 26 H. Open letter of one of the persons sentenced for the murder of Zorig, recently published in the Mongolian media ................................................................ 27 * * * #IPU138 Mongolia © Zorig Foundation Executive Summary From 11 to 13 September 2017, a delegation of the Committee on the Human Rights of Parliamentarians (hereinafter “the Committee”) conducted a mission to Mongolia to obtain further information on the recently concluded judicial proceedings that led to the final conviction of the three accused for the 1998 assassination of Mr. Zorig -

![[Mongolia CO] COVID-19 UNFPA Mongolia CO Sitrep #6](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1739/mongolia-co-covid-19-unfpa-mongolia-co-sitrep-6-71739.webp)

[Mongolia CO] COVID-19 UNFPA Mongolia CO Sitrep #6

R E P O R T I N G P E R I O D : 1 6 - 3 0 , N O V E M B E R , 2 0 2 0 UNFPA MONGOLIA Situation Report #6 on COVID-19 response SITUATION OVERVIEW SITUATION IN NUMBERS Since 15 November, the State Emergency Commission (SEC) has 791 confirmed cases identified a total of eight clusters of COVID-19 transmission: two in Ulaanbaatar City and one in Selenge, Darkhan-Uul, Gobisumber, 383 cases among repatriates Orkhon, Dornogobi and Arkhangai provinces respectively. The clusters are linked with close and secondary contacts of an index case cases from local clusters of COVID-19. The government has taken swift action including 408 contact tracing, the immediate testing of identified contacts, the Ulaanbaatar city isolation of contacts, quarantine, and treatment of positive cases. 77 179 Selenge province A state of all-out readiness, with lockdown measures, was in place 44 Darkhan-Uul province until 6am, 1 December. Movements were controlled in the city and only employees in 13 priority sectors were allowed to travel to and 3 Gobisumber province from their place of work. 22 Orkhon province 21 Dornogobi province To mitigate the spread of the virus, the government has organized random and targeted surveillance testing at various sites to determine 2 Arkhangai province whether there is wider community transmission; it has concluded that Quarantine cluster Mongolia is dealing with cluster transmission. 60 patients recovered The Prime Minister addressed citizens requesting that they follow the 354 government and SEC’s directives and urged everyone to stay at home, wear masks, maintain physical distancing if going outside for essential 428 patients being treated services, and to wash their hands. -

Harvard Polo Asia by Abigail Trafford

Horsing Around IN THE HIGHWAYS AND BYWAYS OF POLO IN ASIA We all meet up during the six-hour stopover in the Beijing Airport. The invitation comes from the Genghis Khan Polo Club to play in Mongolia and then to head back to China for a university tournament at the Metropolitan Polo Club in Tianjin. Say, what? Yes, polo! Both countries are resurrecting the ancient sport—a tale of two cultures—and the Harvard players are to be emissaries to help generate a new ballgame in Asia. In a cavernous airport restaurant, I survey the Harvard Polo Team: Jane is captain of the women’s team; Shawn, captain of the men’s team; George, the quiet one, is a physicist; Danielle, a senior is a German major; Sarah, a biology major; Aemilia writes for the Harvard Crimson. Marina, a mathematician, will join us later. Neil and Johann are incoming freshmen; Merrall, still in high school, is a protégé of the actor Tommy Lee Jones—the godfather of Harvard polo. And where are the grownups? Moon Lai, a friend of Neil’s parents, is the photographer from Minnesota. Crocker Snow, Harvard alum and head of the Edward R. Murrow Center at Tufts, is tour director and coach. I am along as cheer leader and chronicler. We stagger onto the late-night plane to Ulan Bator (UB), the capital of Mongolia, pile into a van and drive into the darkness—always in the constant traffic of trucks. Our first camp of log cabins is near an official site of Naadam—Mongolia’s traditional summer festival of horse racing, wrestling and archery. -

New Documents on Mongolia and the Cold War

Cold War International History Project Bulletin, Issue 16 New Documents on Mongolia and the Cold War Translation and Introduction by Sergey Radchenko1 n a freezing November afternoon in Ulaanbaatar China and Russia fell under the Mongolian sword. However, (Ulan Bator), I climbed the Zaisan hill on the south- after being conquered in the 17th century by the Manchus, Oern end of town to survey the bleak landscape below. the land of the Mongols was divided into two parts—called Black smoke from gers—Mongolian felt houses—blanketed “Outer” and “Inner” Mongolia—and reduced to provincial sta- the valley; very little could be discerned beyond the frozen tus. The inhabitants of Outer Mongolia enjoyed much greater Tuul River. Chilling wind reminded me of the cold, harsh autonomy than their compatriots across the border, and after winter ahead. I thought I should have stayed at home after all the collapse of the Qing dynasty, Outer Mongolia asserted its because my pen froze solid, and I could not scribble a thing right to nationhood. Weak and disorganized, the Mongolian on the documents I carried up with me. These were records religious leadership appealed for help from foreign countries, of Mongolia’s perilous moves on the chessboard of giants: including the United States. But the first foreign troops to its strategy of survival between China and the Soviet Union, appear were Russian soldiers under the command of the noto- and its still poorly understood role in Asia’s Cold War. These riously cruel Baron Ungern who rode past the Zaisan hill in the documents were collected from archival depositories and pri- winter of 1921. -

Climate Change

This “Mongolia Second Assessment Report on Climate Change 2014” (MARCC 2014) has been developed and published by the Ministry of Environment and Green Development of Mongolia with financial support from the GIZ programme “Biodiversity and adaptation of key forest ecosystems to climate change”, which is being implemented in Mongolia on behalf of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development. Copyright © 2014, Ministry of Environment and Green Development of Mongolia Editors-in-chief: Damdin Dagvadorj Zamba Batjargal Luvsan Natsagdorj Disclaimers This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part in any form for educational or non-profit services without special permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. The Ministry of Environment and Green Development of Mongolia would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication that uses this publication as a source. No use of this publication may be made for resale or any other commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from the Ministry of Environment and Green Development of Mongolia. TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures . 3 List of Tables . .. 12 Abbreviations . 14 Units . 17 Foreword . 19 Preface . 22 1. Introduction. Batjargal Z. 27 1.1 Background information about the country . 33 1.2 Introductory information on the second assessment report-MARCC 2014 . 31 2. Climate change: observed changes and future projection . 37 2.1 Global climate change and its regional and local implications. Batjargal Z. 39 2.1.1 Observed global climate change as estimated within IPCC AR5 . 40 2.1.2 Temporary slowing down of the warming . 43 2.1.3 Driving factors of the global climate change . -

Tuul River Mongolia

HEALTHY RIVERS FOR ALL Tuul River Basin Report Card • 1 TUUL RIVER MONGOLIA BASIN HEALTH 2019 REPORT CARD Tuul River Basin Report Card • 2 TUUL RIVER BASIN: OVERVIEW The Tuul River headwaters begin in the Lower As of 2018, 1.45 million people were living within Khentii mountains of the Khan Khentii mountain the Tuul River basin, representing 46% of Mongolia’s range (48030’58.9” N, 108014’08.3” E). The river population, and more than 60% of the country’s flows southwest through the capital of Mongolia, GDP. Due to high levels of human migration into Ulaanbaatar, after which it eventually joins the the basin, land use change within the floodplains, Orkhon River in Orkhontuul soum where the Tuul lack of wastewater treatment within settled areas, River Basin ends (48056’55.1” N, 104047’53.2” E). The and gold mining in Zaamar soum of Tuv aimag and Orkhon River then joins the Selenge River to feed Burenkhangai soum of Bulgan aimag, the Tuul River Lake Baikal in the Russian Federation. The catchment has emerged as the most polluted river in Mongolia. area is approximately 50,000 km2, and the river itself These stressors, combined with a growing water is about 720 km long. Ulaanbaatar is approximately demand and changes in precipitation due to global 470 km upstream from where the Tuul River meets warming, have led to a scarcity of water and an the Orkhon River. interruption of river flow during the spring. The Tuul River basin includes a variety of landscapes Although much research has been conducted on the including mountain taiga and forest steppe in water quality and quantity of the Tuul River, there is the upper catchment, and predominantly steppe no uniform or consistent assessment on the state downstream of Ulaanbaatar City. -

Wildlife Protection in Mongolia by R

196 Oryx Wildlife Protection in Mongolia By R. A. Hibbert CMG Although the Mongolian People's Republic, last refuge of the Przewalski wild horse, is one of the most thinly populated countries in the world, the wildlife decreased considerably in the 30's and 40's. There has been some improvement in recent years, and the Game Law now gives protection to nearly all mammals—the few exceptions include the wolf, understandably in a country with vast herds of domestic animals. Mr. Hibbert, who was British Charge d'Affaires at Ulan Bator from 1964 to 1966, and has since spent a year at Leeds University working on Mongolian materials, assesses the status of the major species of mammals, birds and fish, and describes the game laws. HE Mongolian People's Republic is a huge country with a very T small population. Its area is just over H million square kilometres, its population just over 1,100,000. This gives an average population density of 0-7 per square kilometre or allowing for the concentration of nearly a quarter of the population in the capital at Ulan Bator, a density in rural areas of 0-5 per square kilometre. This seems to be a record low density for a sovereign state. The density of domestic animals—sheep, goats, cows and yaks, horses, camels—is much higher. There are some 24 million domestic animals in the herds, which gives an average density of 15 per square kilometre. Even so, the figures suggest that there is still plenty of room for wild life. -

MONGOLIA: Systematic Country Diagnostic Public Disclosure Authorized

MONGOLIA: Systematic Country Diagnostic Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Acknowledgements This Mongolia Strategic Country Diagnostic was led by Samuel Freije-Rodríguez (lead economist, GPV02) and Tuyen Nguyen (resident representative, IFC Mongolia). The following World Bank Group experts participated in different stages of the production of this diagnostics by providing data, analytical briefs, revisions to several versions of the document, as well as participating in several internal and external seminars: Rabia Ali (senior economist, GED02), Anar Aliyev (corporate governance officer, CESEA), Indra Baatarkhuu (communications associate, EAPEC), Erdene Badarch (operations officer, GSU02), Julie M. Bayking (investment officer, CASPE), Davaadalai Batsuuri (economist, GMTP1), Batmunkh Batbold (senior financial sector specialist, GFCP1), Eileen Burke (senior water resources management specialist, GWA02), Burmaa Chadraaval (investment officer, CM4P4), Yang Chen (urban transport specialist, GTD10), Tungalag Chuluun (senior social protection specialist, GSP02), Badamchimeg Dondog (public sector specialist, GGOEA), Jigjidmaa Dugeree (senior private sector specialist, GMTIP), Bolormaa Enkhbat (WBG analyst, GCCSO), Nicolaus von der Goltz (senior country officer, EACCF), Peter Johansen (senior energy specialist, GEE09), Julian Latimer (senior economist, GMTP1), Ulle Lohmus (senior financial sector specialist, GFCPN), Sitaramachandra Machiraju (senior agribusiness specialist, -

Scanned Using Book Scancenter 5033

Globalization ’s Impact on Mongolian Identity Issues and the Image of Chinggis Khan Alicia J. Campi PART I: The Mongols, this previously unheard-of nation that unexpectedly emerged to terrorize the whole world for two hundred years, disappeared again into obscurity with the advent of firearms. Even so, the name Mongol became one forever familiar to humankind, and the entire stretch of the thirteenth through the fifteenth centuries has come to be known as the Mongol era.' PART II; The historic science was the science, which has been badly affect ed, and the people of Mongolia bid farewell to their history and learned by heart the bistort' with distortion but fuU of ideolog}'. Because of this, the Mong olians started to forget their religious rituals, customs and traditions and the pa triotic feelings of Mongolians turned to the side of perishing as the internation alism was put above aU.^ PART III: For decades, Mongolia had subordinated national identity to So viet priorities __Now, they were set adrift in a sea of uncertainty, and Mongol ians were determined to define themselves as a nation and as a people. The new freedom was an opportunity as well as a crisis." As the three above quotations indicate, identity issues for the Mongolian peoples have always been complicated. In our increas ingly interconnected, media-driven world culture, nations with Baabar, Histoij of Mongolia (Ulaanbaatar: Monsudar Publishing, 1999), 4. 2 “The Political Report of the First Congress of the Mongolian Social-Demo cratic Party” (March 31, 1990), 14. " Tsedendamdyn Batbayar, Mongolia’s Foreign Folicy in the 1990s: New Identity and New Challenges (Ulaanbaatar: Institute for Strategic Studies, 2002), 8. -

Data Collection Survey on Copper Industry Sector in Mongolia Final Report

Mongolia Ministry of Mining DATA COLLECTION SURVEY ON COPPER INDUSTRY SECTOR IN MONGOLIA FINAL REPORT October 2014 Japan International Cooperation Agency(JICA) Mitsubishi Materials Techno Corporation Mitsubishi Research Institute, Inc. I L Sumiko Resources Exploration & Development Co., Ltd JR 14-111 DATA COLLECTION SURVEY ON COPPER INDUSTRY SECTOR IN MONGOLIA FINAL REPORT Table of Contents Table of Contents List of Figures, Tables and Photos List of Abbreviations Chapter 1.Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1 Background of the Survey ...................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1.1 Outlined State of Mining Industries in Mongolia ......................................................... 1-1 1.1.2 Copper Resources in Mongolia ..................................................................................... 1-3 1.2 Purpose of Survey................................................................................................................... 1-5 1.3 Principle for the Execution of the Survey .............................................................................. 1-5 1.4 Flow of Survey ....................................................................................................................... 1-6 1.5 Survey Organization ............................................................................................................... 1-8 1.5.1 Counterpart -

Searching for Antidotes to Globalization : Local Insitutions at Mongolia’S Sacred Bogd Khan Mountain

SEARCHING FOR ANTIDOTES TO GLOBALIZATION : LOCAL INSITUTIONS AT MONGOLIA’S SACRED BOGD KHAN MOUNTAIN by David Tyler Sadoway B.E.S. Hons. Co-op (Urban & Regional Planning), University of Waterloo, 1991. Research Project Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Resource Management in the School of Resource and Environmental Management Report No. 291 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY April 2002 This work may be reproduced in whole or in part. ii Approval page iii A b s t r a c t The Bogd Khan Mountain (Uul) is a sacred natural and cultural site—an island-like forest-steppe mountain massif revered for centuries by Mongolians. This sacred site is also a 41, 651 hectare state-designated ‘Strictly Protected Area’ and a listed UNESCO Biosphere Reserve of global significance (1996). Bogd Khan Uul is adjacent to the nation's capital, largest and fastest growing city—Ulaanbaatar. This case study employs an inter-scale research frame to draw linkages between current resource management problems at Bogd Khan Uul while at the same time examines the capacity of local, national and multilateral institutions to address these. In the process the research provides a glimpse of centuries old Mongol traditions—human ingenuity shaped by understandings that have co-evolved with the cycles of nature. The study provides contemporary insights into the dramatic changes that affected Mongolia and its institutions during its tumultuous global integration in the final decade of the second millennium. The study’s inter-scaled Globalocal Diversity Spiral (GDS) framework focuses upon Bogd Khan Uul site-specific issues of forest and vegetation over-harvest, animal overgrazing and problematic tourism development; and key contextual issues of material poverty and local traditions.