Brown V. Board of Education (1954) an Analysis of Policy Implementation, Outcomes, and Unintended Consequences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Virginia Woolf, Arnold Bennett, and Turn of the Century Consciousness

Colby Quarterly Volume 13 Issue 1 March Article 5 March 1977 The Moment, 1910: Virginia Woolf, Arnold Bennett, and Turn of the Century Consciousness Edwin J. Kenney, Jr. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Library Quarterly, Volume 13, no.1, March 1977, p.42-66 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Kenney, Jr.: The Moment, 1910: Virginia Woolf, Arnold Bennett, and Turn of the The Moment, 1910: Virginia Woolf, Arnold Bennett, and Turn ofthe Century Consciousness by EDWIN J. KENNEY, JR. N THE YEARS 1923-24 Virginia Woolf was embroiled in an argument I with Arnold Bennett about the responsibility of the novelist and the future ofthe novel. In her famous essay "Mr. Bennett and Mrs. Brown," she observed that "on or about December, 1910, human character changed";1 and she proceeded to argue, without specifying the causes or nature of that change, that because human character had changed the novel must change if it were to be a true representation of human life. Since that time the at once assertive and vague remark about 1910, isolated, has served as a convenient point of departure for historians now writing about the social and cultural changes occurring during the Edwardian period.2 Literary critics have taken the ideas about fiction from "Mr. Bennett and Mrs. Brown" and Woolfs other much-antholo gized essay "Modern Fiction" as a free-standing "aesthetic manifesto" of the new novel of sensibility;3 and those who have recorded and discussed the "whole contention" between Virginia Woolf and Arnold Bennett have regarded the relation between Woolfs historical observation and her ideas about the novel either as just a rhetorical strategy or a generational disguise for the expression of class bias against Bennett.4 Yet few readers have asked what Virginia Woolf might have nleant by her remark about 1910 and the novel, or what it might have meant to her. -

Not to Be Published in the Official Reports in The

Filed 11/8/05 P. v. Mendoza CA2/7 Opinion following rehearing NOT TO BE PUBLISHED IN THE OFFICIAL REPORTS California Rules of Court, rule 977(a), prohibits courts and parties from citing or relying on opinions not certified for publication or ordered published, except as specified by rule 977(b). This opinion has not been certified for publication or ordered published for purposes of rule 977. IN THE COURT OF APPEAL OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA SECOND APPELLATE DISTRICT DIVISION SEVEN THE PEOPLE, B162636 Plaintiff and Respondent, (Los Angeles County Super. Ct. Nos. TA 062114, v. TA 063735) JOSE P. MENDOZA, et al., OPINION ON REHEARING Defendants and Appellants. In re ANTHONY J. CONTRERAS, B173722 (Los Angeles County on Habeas Corpus. Super. Ct. No. TA 062114) ORIGINAL PROCEEDING, application for writ of habeas corpus considered with appeals from judgments of the Superior Court of Los Angeles County. John S. Cheroske and Jack W. Morgan, Judges. Writ petition of Contreras granted. Judgment against Rivas reversed, and judgment against Mendoza affirmed as modified. Richard A. Levy, under appointment by the Court of Appeal, for Defendant and Appellant Jose Mendoza. Peter Gold, under appointment by the Court of Appeal, for Defendant and Appellant Jerry Rivas. C. Delaine Renard, under appointment by the Court of Appeal, for Defendant and Appellant Anthony J. Contreras. Bill Lockyer, Attorney General, Robert R. Anderson, Chief Assistant Attorney General, Pamela C. Hamanaka, Senior Assistant Attorney General, Lance E. Winters, Richard Breen and Susan Sullivan Pithey, Deputy Attorneys General, for Plaintiff and Respondent. _________________________________ Defendants Jose Mendoza, Jerry Rivas and Anthony Contreras timely appealed from their convictions for first degree murder. -

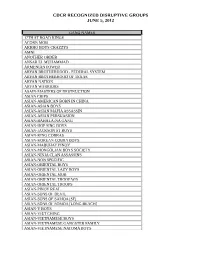

Cdcr Recognized Disruptive Groups June 5, 2012

CDCR RECOGNIZED DISRUPTIVE GROUPS JUNE 5, 2012 GANG NAMES 17TH ST ROAD KINGS ACORN MOB AKRHO BOYS CRAZZYS AMNI ANOTHER ORDER ANSAR EL MUHAMMAD ARMENIAN POWER ARYAN BROTHERHOOD - FEDERAL SYSTEM ARYAN BROTHERHOOD OF TEXAS ARYAN NATION ARYAN WARRIORS ASAIN-MASTERS OF DESTRUCTION ASIAN CRIPS ASIAN-AMERICAN BORN IN CHINA ASIAN-ASIAN BOYS ASIAN-ASIAN MAFIA ASSASSIN ASIAN-ASIAN PERSUASION ASIAN-BAHALA-NA GANG ASIAN-HOP SING BOYS ASIAN-JACKSON ST BOYS ASIAN-KING COBRAS ASIAN-KOREAN COBRA BOYS ASIAN-MABUHAY PINOY ASIAN-MONGOLIAN BOYS SOCIETY ASIAN-NINJA CLAN ASSASSINS ASIAN-NON SPECIFIC ASIAN-ORIENTAL BOYS ASIAN-ORIENTAL LAZY BOYS ASIAN-ORIENTAL MOB ASIAN-ORIENTAL TROOP W/S ASIAN-ORIENTAL TROOPS ASIAN-PINOY REAL ASIAN-SONS OF DEVIL ASIAN-SONS OF SAMOA [SF] ASIAN-SONS OF SOMOA [LONG BEACH] ASIAN-V BOYS ASIAN-VIET CHING ASIAN-VIETNAMESE BOYS ASIAN-VIETNAMESE GANGSTER FAMILY ASIAN-VIETNAMESE NATOMA BOYS CDCR RECOGNIZED DISRUPTIVE GROUPS JUNE 5, 2012 ASIAN-WAH CHING ASIAN-WO HOP TO ATWOOD BABY BLUE WRECKING CREW BARBARIAN BROTHERHOOD BARHOPPERS M.C.C. BELL GARDENS WHITE BOYS BLACK DIAMONDS BLACK GANGSTER DISCIPLE BLACK GANGSTER DISCIPLES NATION BLACK GANGSTERS BLACK INLAND EMPIRE MOB BLACK MENACE MAFIA BLACK P STONE RANGER BLACK PANTHERS BLACK-NON SPECIFIC BLOOD-21 MAIN BLOOD-916 BLOOD-ATHENS PARK BOYS BLOOD-B DOWN BOYS BLOOD-BISHOP 9/2 BLOOD-BISHOPS BLOOD-BLACK P-STONE BLOOD-BLOOD STONE VILLAIN BLOOD-BOULEVARD BOYS BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER [LOT BOYS] BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-BELHAVEN BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-INCKERSON GARDENS BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-NICKERSON -

F E a T U R E S Summer 2021

FEATURES SUMMER 2021 NEW NEW NEW ACTION/ THRILLER NEW NEW NEW NEW NEW 7 BELOW A FISTFUL OF LEAD ADVERSE A group of strangers find themselves stranded after a tour bus Four of the West’s most infamous outlaws assemble to steal a In order to save his sister, a ride-share driver must infiltrate a accident and must ride out a foreboding storm in a house where huge stash of gold. Pursued by the town’s sheriff and his posse. dangerous crime syndicate. brutal murders occurred 100 years earlier. The wet and tired They hide out in the abandoned gold mine where they happen STARRING: Thomas Nicholas (American Pie), Academy Award™ group become targets of an unstoppable evil presence. across another gang of three, who themselves were planning to Nominee Mickey Rourke (The Wrestler), Golden Globe Nominee STARRING: Val Kilmer (Batman Forever), Ving Rhames (Mission hit the very same bank! As tensions rise, things go from bad to Penelope Ann Miller (The Artist), Academy Award™ Nominee Impossible II), Luke Goss (Hellboy II), Bonnie Somerville (A Star worse as they realize they’ve been double crossed, but by who Sean Astin (The Lord of the Ring Trilogy), Golden Globe Nominee Is Born), Matt Barr (Hatfields & McCoys) and how? Lou Diamond Phillips (Courage Under Fire) DIRECTED BY: Kevin Carraway HD AVAILABLE DIRECTED BY: Brian Metcalf PRODUCED BY: Eric Fischer, Warren Ostergard and Terry Rindal USA DVD/VOD RELEASE 4DIGITAL MEDIA PRODUCED BY: Brian Metcalf, Thomas Ian Nicholas HD & 5.1 AVAILABLE WESTERN/ ACTION, 86 Min, 2018 4K, HD & 5.1 AVAILABLE USA DVD RELEASE -

How People Learn Brain, Mind, Experience, and School: Expanded Edition

THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS This PDF is available at http://nap.edu/9853 SHARE How People Learn Brain, Mind, Experience, and School: Expanded Edition DETAILS 384 pages | 7 x 10 | PAPERBACK ISBN 978-0-309-07036-2 | DOI 10.17226/9853 CONTRIBUTORS GET THIS BOOK Committee on Developments in the Science of Learning with additional material from the Committee on Learning Research and Educational Practice, National Research Council FIND RELATED TITLES Visit the National Academies Press at NAP.edu and login or register to get: – Access to free PDF downloads of thousands of scientific reports – 10% off the price of print titles – Email or social media notifications of new titles related to your interests – Special offers and discounts Distribution, posting, or copying of this PDF is strictly prohibited without written permission of the National Academies Press. (Request Permission) Unless otherwise indicated, all materials in this PDF are copyrighted by the National Academy of Sciences. Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. How People Learn Brain, Mind, Experience, and School: Expanded Edition Copyright National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. How People Learn Brain, Mind, Experience, and School: Expanded Edition Expanded Edition How People Learn Brain, Mind, Experience, and School Committee on Developments in the Science of Learning John D. Bransford, Ann L. Brown, and Rodney R. Cocking, editors with additional material from the Committee on Learning Research and Educational Practice M. Suzanne Donovan, John D. Bransford, and James W. Pellegrino, editors Commission on Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education National Research Council NATIONAL ACADEMY PRESS Washington, D.C. Copyright National Academy of Sciences. -

Feminist Periodicals

. The U n vers ty o f w sconsln System Feminist Periodicals A current listing of contents WOMEN'S STUDIES Volume 20, Number I, Spring 2000 Published by Phyllis Holman Weisbard LIBRARIAN Women's Studies Librarian F minist CD Peri 1 Is A current listing of contents Volume 20, Number 1 Spring 2000 Periodical literature is the cutting edge of women's scholarship, feminist theory, and much of women's culture. Feminist Periodicals: A Current Listing of Contents is pUblished by the Office of the University of Wisconsin System Women's Studies Librarian on aquarterly basis with the intentof increasing pUblicawarenessoffeminist periodicals. It is our hope that Feminist Periodicals will serve several purposes: to keep the reader abreast of current topics in feminist literature; to increase readers' familiarity with awide spectrum offeminist periodicals; and to provide the requisite bibliographic information should a reader wish to sUbscribe to ajournal or to obtain a particular article at her library or through interlibrary loan. (Users will need to be aware of the limitations of the new copyright law with regard to photocopying of copyrighted materials.) Table ofcontents pages from current issues of major feministjournals are reproduced in each issue of Feminisf Periodicals, preceded by a comprehensive annotated listing of all journals we have selected. As publication schedules vary enormously, not every periodical will have table of contents pages reproduced in each issue of FP. The annotated listing provides the following information on each journal: 1. Year of first publication. 2. Frequency of pUblication. 3. U.S. subscription price(s). 4. Subscription address. 5. -

You and Your Friends Bsmwrttrmjif- Ladies-Dresses

•]";• "'"-"• / H -v "> {* ',-..' .:"';•• •'* • S!^f5 -SAHWAY JtECOBD. FRIDAY. JULY XL1930 he has Fmd Euly Palestine i: ;: : > :: You and Your Friends Tribe WonUped Dogs i'• : :;-'.'.-'-': - '•',:•- " 'A''- ;.'- v?"v&;^-'.^ ^r'.ys-••;•-•:•••;,--••• r•••• ' •-•••••• ?, • •'•".•y^'^R*:'^few Ofe vni. 3Cn. C«ori»' WEATHER FORECAST TV Doris. Gf (2a- LcodOL—5« Ics<hxa ftOOD ye Today: Fair and continued cool. • Barbara-3C=d«a, cf Tr«o-r-j«ai ; JOC £aatr«f :Ser. tetec Jafcxa Wtoatim B. C) Tomorrow: Fair and somewhat PUBLISHED tea, •spots;? a ICTT days wtaijota' tSe ! Sa. Jc&a Met. 7 the* BTKJ A trite In tbe tcstb of warmer. .TWICE WEEKLY • t*B»«t..S=ieoecjwr ef 23-.3CWS. Ptloda* s£» aroratlped dsp. JonJ street. ' • • j sated Piot.Sr Wmtoa JTlodtn IN RAHWAY'S INTEREST* -fc.' -'sat dtn- Aid Tezrie. i* ttm ttieam et ..*' lectsre The New Jersey Advocate ralTtney eoCej^ London. Io Record nrfMtir Ifcr reCt» of ttg taril- Absorblna Jhe Rihwty Newa-Herald, the tuccewor of the Union D emocrat. Established 1849. Kr. xad 3fa. E tortra. Ptecfenar prfrie «aM.- .- VOL. XIX. SERIAL NO. 2161 -Tbmdo vt Smd- aaa sad &n3T. of.] kxve jBae to flaeJr eotaje « Brf- wSfcfc-we toov.asd « very enrtoas r far tie seaascc: [ Bole Bedd doss «tld hare been EY HflY BRING To Be Honored at Reception . Honored.by Governor Zfcsrrii sate, isd their j eaee «T tJ*l tifiie s*&ed us to na- 6E0. W. STEWART 6IVEN x. Jfcs. C&aries Ben and j dsKaxd tie xaoresests of Je -M«i Fffn?>fft. at0 «e J«Iy a frist 6e«r E»y of two xasKtks la Scodaad. -

Us Colombianidades Program

NOTES FRIDAY, OCTOBER 20th “The Dialectics of Exile in The Veins of the Ocean” Astrid Lorena Ochoa Campo (University of Virginia) Coffee and Pastries: 9:00-9:30AM U.S. “Imposed Exile and Diasporic Estrangement in Vida” Welcome: 9:30-10:00AM Catalina Esguerra (University of Michigan) Panel 1 | 10:00-11:30AM | Mapping Colombianx Spaces across the Americas “Gabo’s Journeys: Spiritual Experiences Lived by Colombians COLOMBIANIDADES in the United States” Moderator: Diane Garbow Néstor Gómez Morales (University of Denver and Iliff School of Theology) “El Hueco: Theorizing a Colombian Metaphor for Undocumented Migration” “Imagining a U.S. Colombianx Diasporic Literature” and the of Jennifer Harford Vargas (Bryn Mawr College) Arielle Concilio (University of California, Santa Barbara) FUTURE “Colombia Park: Pan-Latino, Transnational Urbanism in the Midst SATURDAY, OCTOBER 21st of Gentrification” LATINX STUDIES Johana Londoño (University at Albany, SUNY) Coffee and Pastries: 8:00-9:00AM “Silence in the Terminals: Investigating U.S. Airport Surveillance PANEL 4 | 9:00-10:30AM | Queering Aesthetics of Violence of Colombian Immigrants between 1975-1995” Marcela Osorio (Williams College ‘15) Moderator: Angie Ocampo “‘The Fault of the Jelly’: Interpreting Colombianxamerican Dispossession “Dialogue across Artistic Borders in the Colombianx Diaspora” INAUGURAL in the U.S. Landscape from the Green Revolution to Plan Colombia” Eileen McKiernan González (Berea College) John Mckiernan-González (Texas State University) and For an Interactive Campus Map (best for mobile devices): map.williams.edu INTERDISCIPLINARY Cary Córdova (University of Texas, Austin) “Mi casa, su casa: Shakira and the Colombo-Transnational Queer Performance of Home” How to Access Wifi on the Williams College Campus: SYMPOSIUM Lunch: 11:30-1:30PM Sergio Manrique (Williams College ‘15) Williams College provides free guest wifi access, which you may use while on the Williams campus. -

Pride & Prejudice at Seattle Rep Encore Arts Seattle

OCTOBER 2017 BY KATE HAMILL ADAPTED FROM THE NOVEL BY JANE AUSTEN DIRECTED BY AMANDA DEHNERT SEPTEMBER 29 - OCTOBER 29, 2017 2017/18 SEASON THE ODYSSEY | PRIDE AND PREJUDICE | THE HUMANS | TWO TRAINS RUNNING IBSEN IN CHICAGO | HERSHEY FELDER AS IRVING BERLIN | THE GREAT LEAP | FAMILIAR | MAC BETH September 2017 Volume 37, No. 2 FROM THE ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Paul Heppner Publisher BOARD OF TRUSTEES Susan Peterson Design & Production Director John Keegan Kevin Millison Chair Vice President Ana Alvira, Robin Kessler, Shaun Swick, Stevie VanBronkhorst Earle J. Hereford Becky Lenaburg Production Artists and Graphic Design President Secretary Mike Hathaway Amy Bautista Stellman Keehnel We’ve all seen how a young artist strives to find sources of inspiration, Sales Director Vice President/Treasurer President Elect and to also discover something to push against—a space within the Brieanna Bright, Joey Chapman, Elizabeth Choy, M.D. Terri Olson Miller conversation to step in and make your voice heard. I was reminded of Ann Manning Vice President Chair Emeritus this over the summer when we lost the legendary playwright and actor Seattle Area Account Executives Adam Cornell Sam Shepard. I found his plays in my first year of college and they gave SEATTLE PREMIERE Amelia Heppner, Marilyn Kallins, Terri Reed Vice President San Francisco/Bay Area Account Executives me confidence to tell the stories I wanted to tell. His characters were Braden Abraham† Bruce E.H. Johnson mythical, yet personal, and set against the familiar landscape in which I Carol Yip Clodagh Ash John Keegan grew up. I felt them in my blood. In the world of his imagination, I found Sales Coordinator Susan Ashmun Stellman Keehnel Amy Bautista Deborah T. -

CE 004 846 BO-CEC English Resource Guide

DOCUMENT RESUME e ED 112 080 95 CE 004 846 TITLE BO-CEC English Resource Guide; Grades 7-9. INSTITUTION Colorado State Univ., Ft. Collins. Dept. of Vocational Education. SPONS AGENCY Office of Education (DHEW), Washington, D.C. PUB DATE [75] CONTRACT OEC-0-73-5230 NOTE 360.9.; Some illustrative materials may not reproduce due to smallness of type; For related documents, see CE 004 842-847 EDRS PRICE MF-$0.76 HC-$18.40 Plus Postage DESCRIPTORS *Business Education; *Business English; *Career Education; Career Exploration; Class Activities; Curriculum Enrichment; *Curriculum Guides; *English; English Instruction; Grade 7; Grade 8; Grade 9; Instructional Materials; Learning Activities; Office Occupations Education; Secondary Education; Simulation; Teaching Guides; Unit Plan IDENTIFIERS Business and Office Career Education Curriculum; Project BO CEC ABSTRACT The 20 resource English units which comprise the guide for grades seven-nine are designed to supplement, rather than replace, regular instructional materials and, are intended for use as enrichment materials to use as reinforcement exercises after regular English units have been taught. The purpose of the guide is to give students a chance to explore various business and office occupations while gaining insight into how and why a knowledge of English is important in everyday work life. The units may be adapted to fit special objectives. The first 12 units deal with grammar and the _mechanics of writing, letter writing, the preparing outgoing mail; in all but one, the major activity is a job simulation requiring students to apply their knowledge of the English topic with which the unit deals. Four oral language units each contain two major activities and, as in the first 12, each unit contains a teacher's key, a background information sheet on the occupation, optional activities suggestions, and student worksheets. -

THEORIZING BROWN IDENTITY by Danielle Sandhu a Thesis

THEORIZING BROWN IDENTITY by Danielle Sandhu A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Department of Sociology and Equity Studies in Education University of Toronto © Danielle Sandhu 2014 THEORIZING BROWN IDENTITY Master of Arts 2014 Danielle Sandhu Department of Sociology and Equity Studies in Education University of Toronto Abstract This thesis examines the possibilities and limitations of theorizing Brown identity as an anti-racist and anti-colonial framework. By examining discursive representations of Brownness and Brown Identity in the Brown Canada Project, a community-led project of the Council of Agencies Serving South Asians, it introduces a new framework for conceptualizing the racialization, identity, and resistance of South Asians in the Greater Toronto Area. The thesis reveals three key themes: the salience of Brown identity in terms of a spirit injury that results from migration, assertion of pride in resistance, and how shared values and experiences of racism form pedagogies for education and community-building. These themes inform a theory of Brown identity and Brownness for anti-racist and anti-colonial resistance. This thesis aims to inform anti-racist and anti-colonial educational practices, political activism, and social movements. It serves as a point of generation for new lines of inquiry into Brown epistemologies, experiences, and relationships. ii Acknowledgements This thesis is dedicated to my parents, Paramjit Singh Sandhu and Swarn Lata Chopra Sandhu. Thank you for your sacrifices, your neverending support and encouragement, and love. You taught me about justice, struggle, and resistance from an early age. You are my pillars; my gurus on earth. -

May 2014 P.O

WICHITA AND AFFILIATED TRIBES NEWSLETTER May 2014 P.O. Box 729 Distributed June 3, 2014 Anadarko, OK 73005 Phone: 405.247.2425 Fax: 405.247.2430 [email protected] Website: www.wichitatribe.com Wichita Executive Committee Terms Expire 07/2016 President’s Report Summer is upon us. Wow, just when you AoA Program President think there won’t be enough for the newslet- The Tribe has been trying to address things Terri Parton ter, there ends up being more information with the AoA Program. The AoA cafeteria Vice-President than you can give in 18 pages. Lots of things has been painted, new blinds are up and Jesse E. Jones to let you know about. I hope each of you the kitchen received new flooring. A new find useful information in this newsletter. salad bar has also been purchased to allow Secretary forhealthier choices in the AoA Program. Myles Stephenson Jr. Demographic Survey We continue to try to improve client satisfac- So far we have had 116 Demographic Sur- tion with the meals. According to Roxanne Treasurer veys returned. We are still waiting for the Coker, the AoA Program has seen an in- S. Robert White Jr. NOFA for the ICDBG Grant to be an- crease in participation over the last few nounced. We have extended the end date months. Committee Member again for the Demographic Survey to June Shirley Davilla 30, 2014. You still have time to get yours in. Cobell Settlement Meeting Committee Member On Monday, June 2, 2014, attorney David Children’s Clothing Assistance Karen Thompson Smith attended a meeting at the Wichita Applications for Children’s Clothing Assis- Housing Authority Iscani Gym to discuss the Committee Member tance will be available on July 1, 2014.