THEORIZING BROWN IDENTITY by Danielle Sandhu a Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Getting by High School: Identity Formation and the Educational Achievements of Punjabi Young Men in Surrey, B.C

GETTING BY HIGH SCHOOL: IDENTITY FORMATION AND THE EDUCATIONAL ACHIEVEMENTS OF PUNJABI YOUNG MEN IN SURREY, B.C. by HEATHER DANIELLE FROST M.A., The University of Toronto, 2002 B.A., The University of Toronto, 2000 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Geography) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) December 2010 © Heather Danielle Frost, 2010 Abstract This thesis is concerned with the lives and educational achievements of young Indo-Canadians, specifically the high school aged sons of Punjabi parents who immigrated to Canada beginning in the 1970s, and who were born or who have had the majority of their schooling in Canada‟s public school system. I examine how these young people develop and articulate a sense of who they are in the context of their parents‟ immigration and the extent to which their identities are determined and conditioned by their everyday lives. I also grapple with the implications of identity formation for the educational achievements of second generation youth by addressing how the identity choices made by young Punjabi Canadian men influence their educational performances. Using data collected by the Ministry of Education of British Columbia, I develop a quantitative profile of the educational achievements of Punjabi students enrolled in public secondary schools in the Greater Vancouver Region. This profile indicates that while most Punjabi students are completing secondary school, many, particularly the young men, are graduating with grade point averages at the lower end of the continuum and are failing to meet provincial expectations in Foundation Skills Assessments. -

Austerity Urbanism and the Social Economy

AUSTERITY URBANISM AND THE SOCIAL ECONOMY ALTERNATE ROUTES Edited by Carlo Fanelli and Steve Tufts, 2017 with Jeff Noonan and Jamey Essex © Alternate Routes, 2017 Toronto www.alternateroutes.ca Twitter: @ARjcsr “Alternate Routes” ISSN 1923-7081 (online) ISSN 0702-8865 (print) Alternate Routes: A Journal of Critical Social Research Vol. 28, 2017 Managing Editors: Carlo Fanelli and Steve Tufts Interventions Editors: Jeff Noonan and Jamey Essex Editorial Advisory Board: Nahla Abdo, Dimitry Anastakis, Pat Armstrong, Tim Bartkiw, David Camfield, Nicolas Carrier, Sally Chivers, Wallace Clement, Simten Cosar, Simon Dalby, Aaron Doyle, Ann Duffy, Bryan Evans, Randall Germain, Henry Giroux, Peter Gose, Paul Kellogg, Jacqueline Kennelly, Priscillia Lefebvre, Mark Neocleous, Bryan Palmer, Jamie Peck, Sorpong Peou, Garry Potter, Georgios Papanicolaou, Mi Park, Justin Paulson, Stephanie Ross, George S. Rigakos, Heidi Rimke, Arne Christoph Ruckert, Toby Sanger, Ingo Schmidt, Alan Sears, Mitu Sengupta, Meenal Shrivastava, Janet Lee Siltanen, Susan Jane Spronk, Jim Struthers, Mark P. Thomas, Rosemary Warskett Journal Mandate: Alternate Routes is committed to creating an outlet for critical social research and interdisciplinary inquiry. A broad range of theoretical and methodological approaches are encouraged, including works from academics, labour, and community researchers. Alternate Routes is a publicly accessible academic journal and encourages provocative works that advance or challenge our understandings of historical and contemporary socio-political, -

Virginia Woolf, Arnold Bennett, and Turn of the Century Consciousness

Colby Quarterly Volume 13 Issue 1 March Article 5 March 1977 The Moment, 1910: Virginia Woolf, Arnold Bennett, and Turn of the Century Consciousness Edwin J. Kenney, Jr. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Library Quarterly, Volume 13, no.1, March 1977, p.42-66 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Kenney, Jr.: The Moment, 1910: Virginia Woolf, Arnold Bennett, and Turn of the The Moment, 1910: Virginia Woolf, Arnold Bennett, and Turn ofthe Century Consciousness by EDWIN J. KENNEY, JR. N THE YEARS 1923-24 Virginia Woolf was embroiled in an argument I with Arnold Bennett about the responsibility of the novelist and the future ofthe novel. In her famous essay "Mr. Bennett and Mrs. Brown," she observed that "on or about December, 1910, human character changed";1 and she proceeded to argue, without specifying the causes or nature of that change, that because human character had changed the novel must change if it were to be a true representation of human life. Since that time the at once assertive and vague remark about 1910, isolated, has served as a convenient point of departure for historians now writing about the social and cultural changes occurring during the Edwardian period.2 Literary critics have taken the ideas about fiction from "Mr. Bennett and Mrs. Brown" and Woolfs other much-antholo gized essay "Modern Fiction" as a free-standing "aesthetic manifesto" of the new novel of sensibility;3 and those who have recorded and discussed the "whole contention" between Virginia Woolf and Arnold Bennett have regarded the relation between Woolfs historical observation and her ideas about the novel either as just a rhetorical strategy or a generational disguise for the expression of class bias against Bennett.4 Yet few readers have asked what Virginia Woolf might have nleant by her remark about 1910 and the novel, or what it might have meant to her. -

Experiences of Muslim Female Students in Knoxville: at the Intersection of Race, Gender, and Religion

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 8-2018 Experiences of Muslim Female Students in Knoxville: At the Intersection of Race, Gender, and Religion Nuray Karaman University of Tennessee, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Recommended Citation Karaman, Nuray, "Experiences of Muslim Female Students in Knoxville: At the Intersection of Race, Gender, and Religion. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2018. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/5002 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Nuray Karaman entitled "Experiences of Muslim Female Students in Knoxville: At the Intersection of Race, Gender, and Religion." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Sociology. Michelle M. Christian, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Manuela Ceballos, Harry F. Dahms, Asafa Jalata Accepted for the Council: Dixie L. Thompson Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) Experiences of Muslim Female Students in Knoxville: At the Intersection of Race, Gender, and Religion A Dissertation Presented for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Nuray Karaman August 2018 Copyright © 2018 by Nuray Karaman. -

Not to Be Published in the Official Reports in The

Filed 11/8/05 P. v. Mendoza CA2/7 Opinion following rehearing NOT TO BE PUBLISHED IN THE OFFICIAL REPORTS California Rules of Court, rule 977(a), prohibits courts and parties from citing or relying on opinions not certified for publication or ordered published, except as specified by rule 977(b). This opinion has not been certified for publication or ordered published for purposes of rule 977. IN THE COURT OF APPEAL OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA SECOND APPELLATE DISTRICT DIVISION SEVEN THE PEOPLE, B162636 Plaintiff and Respondent, (Los Angeles County Super. Ct. Nos. TA 062114, v. TA 063735) JOSE P. MENDOZA, et al., OPINION ON REHEARING Defendants and Appellants. In re ANTHONY J. CONTRERAS, B173722 (Los Angeles County on Habeas Corpus. Super. Ct. No. TA 062114) ORIGINAL PROCEEDING, application for writ of habeas corpus considered with appeals from judgments of the Superior Court of Los Angeles County. John S. Cheroske and Jack W. Morgan, Judges. Writ petition of Contreras granted. Judgment against Rivas reversed, and judgment against Mendoza affirmed as modified. Richard A. Levy, under appointment by the Court of Appeal, for Defendant and Appellant Jose Mendoza. Peter Gold, under appointment by the Court of Appeal, for Defendant and Appellant Jerry Rivas. C. Delaine Renard, under appointment by the Court of Appeal, for Defendant and Appellant Anthony J. Contreras. Bill Lockyer, Attorney General, Robert R. Anderson, Chief Assistant Attorney General, Pamela C. Hamanaka, Senior Assistant Attorney General, Lance E. Winters, Richard Breen and Susan Sullivan Pithey, Deputy Attorneys General, for Plaintiff and Respondent. _________________________________ Defendants Jose Mendoza, Jerry Rivas and Anthony Contreras timely appealed from their convictions for first degree murder. -

Native Language Identification

Native Language Identification: a Simple n-gram Based Approach Binod Gyawali and Gabriela Ramirez and Thamar Solorio CoRAL Lab Department of Computer and Information Sciences University of Alabama at Birmingham Birmingham, Alabama, USA {bgyawali,gabyrr,solorio}@cis.uab.edu Abstract identified by age, gender, geographic origin, level of education and native language. The idea of identi- This paper describes our approaches to Na- fying the native language based on the manner of tive Language Identification (NLI) for the NLI speaking and writing a second language is borrowed shared task 2013. NLI as a sub area of au- from Second Language Acquisition (SLA), where thor profiling focuses on identifying the first language of an author given a text in his sec- this is known as language transfer. The theory of ond language. Researchers have reported sev- language transfer says that the first language (L1) eral sets of features that have achieved rel- influences the way that a second language (L2) is atively good performance in this task. The learned (Ahn, 2011; Tsur and Rappoport, 2007). type of features used in such works are: lex- According to this theory, if we learn to identify what ical, syntactic and stylistic features, depen- is being transfered from one language to another, dency parsers, psycholinguistic features and then it is possible to identify the native language of grammatical errors. In our approaches, we se- lected lexical and syntactic features based on an author given a text written in L2. For instance, n-grams of characters, words, Penn TreeBank a Korean native speaker can be identified by the er- (PTB) and Universal Parts Of Speech (POS) rors in the use of articles a and the in his English tagsets, and perplexity values of character of writings due to the lack of similar function words in n-grams to build four different models. -

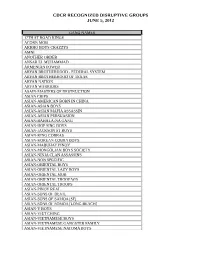

Cdcr Recognized Disruptive Groups June 5, 2012

CDCR RECOGNIZED DISRUPTIVE GROUPS JUNE 5, 2012 GANG NAMES 17TH ST ROAD KINGS ACORN MOB AKRHO BOYS CRAZZYS AMNI ANOTHER ORDER ANSAR EL MUHAMMAD ARMENIAN POWER ARYAN BROTHERHOOD - FEDERAL SYSTEM ARYAN BROTHERHOOD OF TEXAS ARYAN NATION ARYAN WARRIORS ASAIN-MASTERS OF DESTRUCTION ASIAN CRIPS ASIAN-AMERICAN BORN IN CHINA ASIAN-ASIAN BOYS ASIAN-ASIAN MAFIA ASSASSIN ASIAN-ASIAN PERSUASION ASIAN-BAHALA-NA GANG ASIAN-HOP SING BOYS ASIAN-JACKSON ST BOYS ASIAN-KING COBRAS ASIAN-KOREAN COBRA BOYS ASIAN-MABUHAY PINOY ASIAN-MONGOLIAN BOYS SOCIETY ASIAN-NINJA CLAN ASSASSINS ASIAN-NON SPECIFIC ASIAN-ORIENTAL BOYS ASIAN-ORIENTAL LAZY BOYS ASIAN-ORIENTAL MOB ASIAN-ORIENTAL TROOP W/S ASIAN-ORIENTAL TROOPS ASIAN-PINOY REAL ASIAN-SONS OF DEVIL ASIAN-SONS OF SAMOA [SF] ASIAN-SONS OF SOMOA [LONG BEACH] ASIAN-V BOYS ASIAN-VIET CHING ASIAN-VIETNAMESE BOYS ASIAN-VIETNAMESE GANGSTER FAMILY ASIAN-VIETNAMESE NATOMA BOYS CDCR RECOGNIZED DISRUPTIVE GROUPS JUNE 5, 2012 ASIAN-WAH CHING ASIAN-WO HOP TO ATWOOD BABY BLUE WRECKING CREW BARBARIAN BROTHERHOOD BARHOPPERS M.C.C. BELL GARDENS WHITE BOYS BLACK DIAMONDS BLACK GANGSTER DISCIPLE BLACK GANGSTER DISCIPLES NATION BLACK GANGSTERS BLACK INLAND EMPIRE MOB BLACK MENACE MAFIA BLACK P STONE RANGER BLACK PANTHERS BLACK-NON SPECIFIC BLOOD-21 MAIN BLOOD-916 BLOOD-ATHENS PARK BOYS BLOOD-B DOWN BOYS BLOOD-BISHOP 9/2 BLOOD-BISHOPS BLOOD-BLACK P-STONE BLOOD-BLOOD STONE VILLAIN BLOOD-BOULEVARD BOYS BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER [LOT BOYS] BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-BELHAVEN BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-INCKERSON GARDENS BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-NICKERSON -

F E a T U R E S Summer 2021

FEATURES SUMMER 2021 NEW NEW NEW ACTION/ THRILLER NEW NEW NEW NEW NEW 7 BELOW A FISTFUL OF LEAD ADVERSE A group of strangers find themselves stranded after a tour bus Four of the West’s most infamous outlaws assemble to steal a In order to save his sister, a ride-share driver must infiltrate a accident and must ride out a foreboding storm in a house where huge stash of gold. Pursued by the town’s sheriff and his posse. dangerous crime syndicate. brutal murders occurred 100 years earlier. The wet and tired They hide out in the abandoned gold mine where they happen STARRING: Thomas Nicholas (American Pie), Academy Award™ group become targets of an unstoppable evil presence. across another gang of three, who themselves were planning to Nominee Mickey Rourke (The Wrestler), Golden Globe Nominee STARRING: Val Kilmer (Batman Forever), Ving Rhames (Mission hit the very same bank! As tensions rise, things go from bad to Penelope Ann Miller (The Artist), Academy Award™ Nominee Impossible II), Luke Goss (Hellboy II), Bonnie Somerville (A Star worse as they realize they’ve been double crossed, but by who Sean Astin (The Lord of the Ring Trilogy), Golden Globe Nominee Is Born), Matt Barr (Hatfields & McCoys) and how? Lou Diamond Phillips (Courage Under Fire) DIRECTED BY: Kevin Carraway HD AVAILABLE DIRECTED BY: Brian Metcalf PRODUCED BY: Eric Fischer, Warren Ostergard and Terry Rindal USA DVD/VOD RELEASE 4DIGITAL MEDIA PRODUCED BY: Brian Metcalf, Thomas Ian Nicholas HD & 5.1 AVAILABLE WESTERN/ ACTION, 86 Min, 2018 4K, HD & 5.1 AVAILABLE USA DVD RELEASE -

The Fragility of Fear: the Contentious Politics of Emotion and Security in Canada

The Fragility of Fear: the Contentious Politics of Emotion and Security in Canada by Eric Van Rythoven A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In Political Science Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario ©2017, Eric Van Rythoven Abstract International Relations (IR) theory commonly holds security arguments as powerful instruments of political mobilization because they work to instill, circulate, and intensify popular fears over a threat to a community. Missing from this view is how security arguments often provoke a much wider range of emotional reactions, many of which frustrate and constrain state officials’ attempts to frame issues as security problems. This dissertation offers a corrective by outlining a theory of the contentious politics of emotion and security. Drawing inspiration from a variety of different social theorists of emotion, including Goffman’s interactionist sociology, this approach treats emotions as emerging from distinctive repertoires of social interaction. These emotions play a key role in enabling audiences to sort through the sound and noise of security discourse by indexing the significance of different events to our bodies. Yet popular emotions are rarely harmonious; they’re socialized and circulated through a myriad of different pathways. Different repertoires of interaction in popular culture, public rituals, and memorialization leave audiences with different ways of feeling about putative threats. The result is mixed and contentious emotions which shape both opportunities and constraints for new security policies. The empirical purchase of this theory is illustrated with two cases drawn from the Canadian context: indigenous protest and the F-35 procurement. -

Global Law Scholars 2018-2019

Global Law Scholars 2018-2019 Class of 2021 Gabriela Balbin Gabriela Balbín is a J.D. candidate with an interest in international anti-corruption law, national security law, and transitional justice in post-conflict societies. Raised between New York and Spain, Gabriela graduated high school from the American School of Madrid and earned her B.A. in 2015 from Cornell University in Political Science with minors in International Relations, Middle Eastern Studies, and Anthropology. During her undergraduate career, she interned at the Council on Foreign Relations in Washington D.C. and New York and spent a summer studying European politics and working at Helsinki España, a human rights non-profit in Madrid. Prior to starting law school, Gabriela worked for the United States Attorney’s Office in the Eastern District of New York as a litigation analyst in the Business and Securities Fraud Section. After two and a half years at EDNY and spending nearly a year in Judge Matsumoto’s courtroom working on two major trials, she left New York for Europe, making Spain her home-base for her last six months before law school. Gabriela enjoys traveling, hiking, and is an avid vinyl collector. Kemeng Fan Kemeng Fan graduated Cum Laude from Boston College in 2017 with a Bachelor of Arts in Philosophy. Born and raised in Taiyuan, China, he came to the U.S. as an international student to enter the tenth grade. He studied in Massachusetts during high school and college (where he heroically attempted and failed to memorize the correct spelling of the state’s name like many before him). -

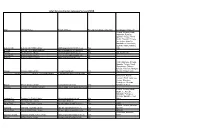

Foreign Language Collections

Adult Services Foreign Language Survey 9/2018 City Library Name Email Address Foreign Language collection Languages Covered? French, German, Hindi, Japanese, Russian, Spanish, Telugu, Tamil, Arabic, Bengali, Chinese (not broken down by Mandarin or Cantonese), Gujarati, Italian, Marathi, Auburn Hills Auburn Hills Public Library [email protected] Yes Urdu Belleville Belleville Area District Library [email protected] No Berkley Berkley Public Library [email protected] Yes ESL books only. Birmingham Baldwin Public Library [email protected] No Brighton Brighton District Library [email protected] No Hindi, Japanese, Korean, Spanish, Telugu, Tamil, Vietnamese, Chinese, Bengali, Kannada, Malayan, Canton Canton Public Library [email protected] Yes Marathi, Panjabi, Urdu Commerce TownshipCommerce Township Community Library [email protected] No Cantonese, French, German, Hindi, Japanese, Korean, Mandarin, Portuguese, Russian, Dexter Dexter District Library [email protected] Yes Spanish, Hebrew Ferndale Ferndale Area District Library [email protected] Yes French, German, Hindi, Japanese, Korean, Mandarin, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish, Tamil, Garden City Garden City Public Library [email protected] Yes Other Hamburg, MI Hamburg Twp. Library [email protected] No Hazel Park Hazel Park District Library [email protected] Yes Arabic French, German, Russian, Highland Highland Township Library [email protected] Yes Spanish Lincoln -

Intergenerational Conversations in a South Asian – Canadian Family

Negotiating Identity: Intergenerational Conversations in a South Asian – Canadian Family Sonia Dhaliwal A Thesis In the Department Of History Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts (History) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada August 2020 © Sonia Dhaliwal, 2020 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY School of Graduate Studies This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Sonia Dhaliwal Entitled: “Negotiating Identity: Intergenerational Conversations in a South Asian-Canadian Family and submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (History) and complies with the rules of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final Examining committee _______________________________ Chair Dr. Peter Gossage ________________________________ Examiner Dr. Rachel Berger ________________________________ Examiner Dr. Cynthia Hammond ________________________________ Supervisor Dr. Barbara Lorenzkowski Approved by ______________________________________ Dr. Peter Gossage, Interim Graduate Program Director ________________, 2020 ________________________________________________ Dr. Pascale Sicotte, Dean of the Faculty of Arts & Science iii Abstract Negotiating Identity: Intergenerational Conversations in a South Asian – Canadian Family Sonia Dhaliwal This thesis investigates change over time within a diasporic community in Canada using oral history methodologies with four generations of a South Asian-Canadian family. Using