Silicon-Based Fertilizer Applications Have No Effect on the Reproduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feeding Damage of the Introduced Leafhopper Sophonia Rufofascia (Homoptera: Cicadellidae) to Plants in Forests and Watersheds of the Hawaiian Islands

POPULATION AND COMMUNITY ECOLOGY Feeding Damage of the Introduced Leafhopper Sophonia rufofascia (Homoptera: Cicadellidae) to Plants in Forests and Watersheds of the Hawaiian Islands VINCENT P. JONES, PUANANI ANDERSON-WONG, PETER A. FOLLETT,1 PINGJUN YANG, 2 3 DAPHNE M. WESTCOT, JOHN S. HU, AND DIANE E. ULLMAN Department of Entomology, University of Hawaii at Manoa, Honolulu, HI 96822 Environ. Entomol. 29(2): 171Ð180 (2000) ABSTRACT Experiments were performed to determine the role of the leafhopper Sophonia rufofascia (Kuoh & Kuoh) in damage observed on forest and watershed plants in the Hawaiian Islands. Laboratory manipulation of leafhopper populations on Þddlewood, Citharexylum spinosum L., caused interveinal chlorosis and vein browning on young fully expanded leaves similar to that observed on leafhopper infested plants seen in the Þeld and necrosis on older leaves. Field studies with caged “uluhe” fern, Dicranopteris linearis (Burman), demonstrated that frond veins turned brown within2dofleafhopper feeding; and by 141 d after feeding, an average of 85% of the surface area of the fronds were necrotic compared with only 12% necrosis in untreated cages. Field trials with stump-cut Þretree, Myrica faya Aiton, were performed to determine the effect of leafhopper feeding on new growth. Our studies showed that the new growth in exclusion cages had signiÞcantly greater stem length and diameter, a higher number of nodes, fewer damaged leaves, and almost twice as much leaf area compared with plants caged but with the sides left open to permit leafhopper access. Microscopic examination of sections through damaged areas of several leafhopper host plants showed vascular bundle abnormalities similar to those associated with hopperburn caused by potato leafhopper, Empoasca fabae (Harris), feeding on alfalfa. -

Plant Life MagillS Encyclopedia of Science

MAGILLS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF SCIENCE PLANT LIFE MAGILLS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF SCIENCE PLANT LIFE Volume 4 Sustainable Forestry–Zygomycetes Indexes Editor Bryan D. Ness, Ph.D. Pacific Union College, Department of Biology Project Editor Christina J. Moose Salem Press, Inc. Pasadena, California Hackensack, New Jersey Editor in Chief: Dawn P. Dawson Managing Editor: Christina J. Moose Photograph Editor: Philip Bader Manuscript Editor: Elizabeth Ferry Slocum Production Editor: Joyce I. Buchea Assistant Editor: Andrea E. Miller Page Design and Graphics: James Hutson Research Supervisor: Jeffry Jensen Layout: William Zimmerman Acquisitions Editor: Mark Rehn Illustrator: Kimberly L. Dawson Kurnizki Copyright © 2003, by Salem Press, Inc. All rights in this book are reserved. No part of this work may be used or reproduced in any manner what- soever or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy,recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the copyright owner except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information address the publisher, Salem Press, Inc., P.O. Box 50062, Pasadena, California 91115. Some of the updated and revised essays in this work originally appeared in Magill’s Survey of Science: Life Science (1991), Magill’s Survey of Science: Life Science, Supplement (1998), Natural Resources (1998), Encyclopedia of Genetics (1999), Encyclopedia of Environmental Issues (2000), World Geography (2001), and Earth Science (2001). ∞ The paper used in these volumes conforms to the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48-1992 (R1997). Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Magill’s encyclopedia of science : plant life / edited by Bryan D. -

III III USOOPPO9323P United States Patent (19) (11 Patent Number: Plant 9,323 Van Der Knaap 45

III III USOOPPO9323P United States Patent (19) (11 Patent Number: Plant 9,323 van der Knaap 45. Date of Patent: Oct. 10, 1995 54 FICUS LYRATA PLANT NAMED BAMBINO+2 Attorney, Agent, or Firm-Burns, Doane, Swecker & Mathis 76 Inventor: Eduard J. M. van der Knaap, 57 ABSTRACT Wilgenlei 15, 2665 KN Bleiswijk, A new and distinct Ficus lyrata cultivar named Bambino is Netherlands provided that is well suited for growing in pots as an attractive foliage plant. The growth habit of the new cultivar (21) Appl. No.: 354,143 is extremely compact. The leaves are uniformly green with 22 Filed: Dec. 6, 1994 light venation and lack variegation. The leaves also are smaller and thicker than those commonly exhibited by Ficus (51) Int. Cl. ..................................... A01H 5700 lyrata. Additionally, the petioles are extremely short when 52 U.S. Cl. ........................................................ Pt/88.9 compared to those commonly exhibited by Ficus lyrata. 58 Field of Search ................................... Plt./33.1, 88.9 Primary Examiner-James R. Feyrer 2 Drawing Sheets 1. 2 SUMMARY OF THE INVENTION FIG. 1 illustrates a typical potted plant of the Bambino The present invention comprises a new and distinct cultivar wherein the attractive glossy foliage and extremely Fiddle-Leaf Fig cultivar name Bambino. compact growth habit are apparent. Ficus lyrata plants frequently are potted and are grown as FIG. 2 illustrates for comparative purposes plants of the ornamental foliage plants. Commonly, such plants are not same age prepared from vegetative cuttings wherein the new sold by cultivar designation; however, Ficus lyrata plants of Bambino cultivar is shown on the right and a typical Ficus the Full Speed and Goldy cultivars are established and lyrata plant is shown on the left. -

Ornamental Garden Plants of the Guianas Pt. 2

Surinam (Pulle, 1906). 8. Gliricidia Kunth & Endlicher Unarmed, deciduous trees and shrubs. Leaves alternate, petiolate, odd-pinnate, 1- pinnate. Inflorescence an axillary, many-flowered raceme. Flowers papilionaceous; sepals united in a cupuliform, weakly 5-toothed tube; standard petal reflexed; keel incurved, the petals united. Stamens 10; 9 united by the filaments in a tube, 1 free. Fruit dehiscent, flat, narrow; seeds numerous. 1. Gliricidia sepium (Jacquin) Kunth ex Grisebach, Abhandlungen der Akademie der Wissenschaften, Gottingen 7: 52 (1857). MADRE DE CACAO (Surinam); ACACIA DES ANTILLES (French Guiana). Tree to 9 m; branches hairy when young; poisonous. Leaves with 4-8 pairs of leaflets; leaflets elliptical, acuminate, often dark-spotted or -blotched beneath, to 7 x 3 (-4) cm. Inflorescence to 15 cm. Petals pale purplish-pink, c.1.2 cm; standard petal marked with yellow from middle to base. Fruit narrowly oblong, somewhat woody, to 15 x 1.2 cm; seeds up to 11 per fruit. Range: Mexico to South America. Grown as an ornamental in the Botanic Gardens, Georgetown, Guyana (Index Seminum, 1982) and in French Guiana (de Granville, 1985). Grown as a shade tree in Surinam (Ostendorf, 1962). In tropical America this species is often interplanted with coffee and cacao trees to shade them; it is recommended for intensified utilization as a fuelwood for the humid tropics (National Academy of Sciences, 1980; Little, 1983). 9. Pterocarpus Jacquin Unarmed, nearly evergreen trees, sometimes lianas. Leaves alternate, petiolate, odd- pinnate, 1-pinnate; leaflets alternate. Inflorescence an axillary or terminal panicle or raceme. Flowers papilionaceous; sepals united in an unequally 5-toothed tube; standard and wing petals crisped (wavy); keel petals free or nearly so. -

Ficus Plants for Hawai'i Landscapes

Ornamentals and Flowers May 2007 OF-34 Ficus Plants for Hawai‘i Landscapes Melvin Wong Department of Tropical Plant and Soil Sciences icus, the fig genus, is part of the family Moraceae. Many ornamental Ficus species exist, and probably FJackfruit, breadfruit, cecropia, and mulberry also the most colorful one is Ficus elastica ‘Schrijveriana’ belong to this family. The objective of this publication (Fig. 8). Other Ficus elastica cultivars are ‘Abidjan’ (Fig. is to list the common fig plants used in landscaping and 9), ‘Decora’ (Fig. 10), ‘Asahi’ (Fig. 11), and ‘Gold’ (Fig. identify some of the species found in botanical gardens 12). Other banyan trees are Ficus lacor (pakur tree), in Hawai‘i. which can be seen at Foster Garden, O‘ahu, Ficus When we think of ficus (banyan) trees, we often think benjamina ‘Comosa’ (comosa benjamina, Fig. 13), of large trees with aerial roots. This is certainly accurate which can be seen on the UH Mänoa campus, Ficus for Ficus benghalensis (Indian banyan), Ficus micro neriifolia ‘Nemoralis’ (Fig. 14), which can be seen at carpa (Chinese banyan), and many others. Ficus the UH Lyon Arboretum, and Ficus rubiginosa (rusty benghalensis (Indian banyan, Fig. 1) are the large ban fig, Fig. 15). yans located in the center of Thomas Square in Hono In tropical rain forests, many birds and other animals lulu; the species is also featured in Disneyland (although feed on the fruits of different Ficus species. In Hawaii the tree there is artificial). Ficus microcarpa (Chinese this can be a negative feature, because large numbers of banyan, Fig. -

Some “Green” Alternatives for Winter

Winter 2007 / Vol. 3, No. 2 Friends In This Issue… 02 Director’s Message Some “Green” Alternatives for Winter 03 A Winter Bird Walk Rick Meader 04 Development Matters As winter begins, you may be The forms of trees and shrubs become very contemplating your landscape evident in winter. Their underlying shape, masked Curator’s Corner by luxuriant foliage in the summer, becomes 05 and wondering where the color is. Unless your exposed and available for closer inspection during yard resembles a Christmas tree farm or nursery Updates our “naked tree” months. The strongly horizontal 06 teeming with evergreens, you probably are missing limbs of the non-evergreen conifer, tamarack Happenings the friendly sight of green as your foliage becomes 07 (Larix laricina), and cockspur hawthorn (Crataegus compost. If this is the case, you may be missing out Registration, p. 14 crus-galli) can become magical with a light covering More Happenings, p. 20 on subtle but quite interesting textures and colors of frost or snow. The cascading canopy of weeping offered by some deciduous trees and shrubs and cherry (Prunus subhirtella) trees can create a virtual 09 Calendar other herbaceous material. icy waterfall after an ice storm or night of hoarfrost. One of the joys of winter that helps compensate Profile The gnarled, twisting branches of contorted 15 for the loss of foliage and the shortening of the days American hazelnut (Corylus americana ‘Contorta’ ) From the Editor is the new openness of the canopy. The sunlight can actually match your own body shape on a frigid Arb & Gardens in the that is available reaches right down to the ground Press (and in a Salad) January morning. -

Ficus Lyrata Fiddle-Leaf Fig, Banjo Fig Ficus Lyrata Is Native to Tropical Cameroon in Africa and Is in Mulberry Family, Moraceae

435 W. Glenside Ave. The Gardener’s Resource Glenside, PA 19038 Since 1943 215-887-7500 Ficus lyrata Fiddle-Leaf Fig, Banjo Fig Ficus lyrata is native to tropical Cameroon in Africa and is in mulberry family, Moraceae. Its natural environment is hot, humid and it rains often but lightly. They have giant green leaves with lots of cells that need lots of sunlight for food production. The Fiddle is like other plants, in that it uses the sun’s energy for food, but the Fiddle’s leaves are giant compared to most other plants, so they’ll need lots of sunlight. If the leaves are dropping, the plant is not getting enough Feed the plant once during the Spring light. Fiddles are going to need consistent, and then monthly throughout the bright, filtered, sunlight. Turn the plant Summer. Over-fertilization can cause the every few months once it begins to lean Fiddle Leaf Fig to grow leggy and can towards the light. It prefers an east-facing, even kill it. No fertilizer is necessary sunny window as afternoon sun from a south during the Winter when plant growth or west facing window is too strong and will naturally slows down. burn the leaves. TIPS: Water when the top 50%-75% of the soil • Fiddles do well in temperatures becomes dry, then thoroughly drench until between 60-80°F. the water drains into the saucer. Empty the • Keep the plant away from air saucer if the water level is high so as not to conditioners, drafts and heating drown the roots. -

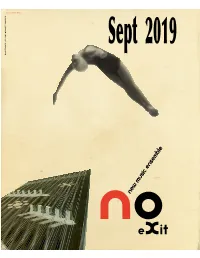

NO EXIT New Music Ensemble

edwin wade design noexitnewmusic Sept 2019 noexitnewmusic.com le ic ensemb us m w ne NoExit New Music Ensemble from left to right; James Rhodes, Nicholas Underhill, Sean Gabriel, James Praznik, Nick Diodore, Edwin Wade, Cara Tweed, Timothy Beyer, Gunnar Owen Hirthe and Luke Rinderknecht. Since its inception, the idea behind noexit has been to serve as an outlet for the commission and performance of contemporary avant-garde concert music. Now in our 11th season and with over 140 commissions to date, NoExit is going strong in our efforts to promote the music of living composers and to be an impetus for the creation of new works. We have strived to create exciting, meaningful and thought-provoking programs; always with the philosophy of bringing the concert hall to the community (not the other way around) and by presenting our programs in a manner which allows for our audience to really connect with the experience......... free and open to the public in every sense. For our 2019-2020 season, NoExit will be welcoming a very special guest, cimbalom virtuoso Chester Englander, who will be performing with NoExit over the next two seasons as part of an ambitious project to commission and record 2 CD’s of all new work. As always, there will be more world premiere music than you can count on one hand (we have 10 new pieces planned for this season). We are particularly happy to be presenting the music of 5 very impressive and talented student composers from Northeast Ohio, representing various colleges from the area. As in past seasons, the ensemble will be participating in the NEOSonicFest, collaborating with Zeitgeist (our favorite co-consprirators) and so much more. -

Morphological Diversity and Function of the Stigma in Ficus Species (Moraceae) Simone Pádua Teixeira, Marina F.B

Morphological diversity and function of the stigma in Ficus species (Moraceae) Simone Pádua Teixeira, Marina F.B. Costa, João Paulo Basso-Alves, Finn Kjellberg, Rodrigo A.S. Pereira To cite this version: Simone Pádua Teixeira, Marina F.B. Costa, João Paulo Basso-Alves, Finn Kjellberg, Rodrigo A.S. Pereira. Morphological diversity and function of the stigma in Ficus species (Moraceae). Acta Oeco- logica, Elsevier, 2018, 90, pp.117-131. 10.1016/j.actao.2018.02.008. hal-02333104 HAL Id: hal-02333104 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02333104 Submitted on 25 Oct 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Morphological diversity and function of the stigma in Ficus species (Moraceae) Simone Pádua Teixeiraa,∗, Marina F.B. Costaa,b, João Paulo Basso-Alvesb,c, Finn Kjellbergd, Rodrigo A.S. Pereirae a Faculdade de Ciências Farmacêuticas de Ribeirão Preto, Universidade de São Paulo, Av. do Café, s/n, 14040-903, Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brazil b PPG em Biologia Vegetal, Instituto de Biologia, Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Av. Bandeirantes, 3900, 14040-901, Campinas, SP, Brazil c Instituto de Pesquisa do Jardim Botânico do Rio de Janeiro, DIPEQ, Rua Pacheco Leão, 915, 22460-030, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil d CEFE UMR 5175, CNRS, Université de Montpellier, Université Paul-Valéry Montpellier, EPHE, 1919 route de Mende, F-34293, Montpellier Cédex 5, France e Faculdade de Filosofia, Ciências e Letras de Ribeirão Preto, Universidade de São Paulo, Av. -

Dutch Growers Garden Centre Fiddle Leaf

Plant Finder Fiddle Leaf Fig Ficus lyrata Height: 40 feet Spread: 30 feet Sunlight: Hardiness Zone: 9b Other Names: Fiddleleaf Fig, Fiddle-leaf Fig Description: Primarily grown for foliage, with huge, fiddle shaped leaves; in frost free areas this variety can grow quite large, howerver it can be maintained as a house or patio plant in colder climates; rarely flowers or fruits outside native habitat Fiddle Leaf Fig Photo courtesy of NetPS Plant Finder Ornamental Features Fiddle Leaf Fig has attractive green foliage with chartreuse veins. The large glossy oval leaves are highly ornamental and remain green throughout the winter. Neither the flowers nor the fruit are ornamentally significant. Landscape Attributes Fiddle Leaf Fig is a multi-stemmed evergreen tree with a shapely oval form. Its average texture blends into the landscape, but can be balanced by one or two finer or coarser trees or shrubs for an effective composition. This tree will require occasional maintenance and upkeep, and is best pruned in late winter once the threat of extreme cold has passed. It is a good choice for attracting birds to your yard, but is not particularly attractive to deer who tend to leave it alone in favor of tastier treats. Gardeners should be aware of the following characteristic(s) that may warrant special consideration; - Insects Fiddle Leaf Fig fruit Fiddle Leaf Fig is recommended for the following landscape Photo courtesy of NetPS Plant Finder applications; 3320 Pasqua Street | Regina, SK | S4S 7G8 Phone: (306) 721-4769 (GROW) | Fax: (306) 584-3808 Website: dutchgrowers.net Plant Finder - Accent - Shade - Hedges/Screening Planting & Growing Fiddle Leaf Fig will grow to be about 40 feet tall at maturity, with a spread of 30 feet. -

Ornamental Ficus Diseases: Identification and Control in Commercial Greenhouse Operations1 D

PP308 Ornamental Ficus Diseases: Identification and Control in Commercial Greenhouse Operations1 D. J. Norman and Gul Shad Ali2 Introduction new introduction with long, narrow, willow-like leaves. ‘Alii’ is particularly well suited for medium-sized tree While edible figs (Ficus carica) are grown agronomically for production. F. pumila (repens) is a popular vine often used delicious fruit, many Ficus species have been commercial- for groundcover and topiary design in outdoor areas. It is ized for decorative, ornamental purposes (Figure 1). These cold tolerant to Zone 8. During the past 20 years, Florida horticultural Ficus varieties are used for interiorscape nurserymen have listed more than 40 different species and houseplant décor and for outdoor landscape design. cultivars of Ficus for sale. These plants are sold in a wide This article provides guidelines for the identification and range of container sizes for indoor and outdoor applications treatment of diseases that may be encountered during the (Henley 1991). commercial production of ornamental Ficus. Ficus The genus Ficus consists of more than 800 species, many of which are desirable foliage plants. Most ornamental Ficus are used as interior trees; however, a few are shrublike or grow as vines (Henley and Poole 1989). F. benjamina, the weeping fig, was first introduced to Florida’s nursery industry during the late 1950s and has since become the most popular interior tree. F. elastica, the India rubber tree, was grown extensively during the early 1950s; however, today this variety is difficult to find because it has been replaced with newer cultivars. F. lyrata, known as fiddleleaf fig, has the largest leaf size among interiorscape Ficus. -

Light and Moisture Requirements for Selected Indoor Plants

Light and Moisture Requirements For Selected Indoor Plants The following list includes most of the indoor plants that you will be growing. This list contains information on how large the plant will get at maturity, which light level is best for good growth, how much you should be feeding your indoor plants and how much water is required for healthy growth. The list gives the scientific name and, in parenthesis, the common name. Always try to remember a plant by its scientific name, because some plants have many common names but only one scientific name. The following descriptions define the terms used in the following material. Light Levels Low - Minimum high level of 25-foot candles, preferred level of 75- to 200-foot candles. Medium - Minimum of 75- to 100-foot candles, preferred level of 200- to 500-foot candles. High - Minimum of 200-foot candles, preferred level of 500- to 1,000-foot candles. Very High - Minimum of 1,000-foot candles, preferred level of over 1,000-foot candles. Water Requirements Dry - Does not need very much water and can stand low humidity. Moist - Requires a moderate amount of water and loves some humidity in the atmosphere. Wet -- Usually requires more water than other plants and must have high humidity in its surroundings. Fertility General Rule - One teaspoon soluble house plant fertilizer per gallon of water or follow recommendations on package. Low - No application in winter or during dormant periods. Medium - Apply every other month during winter and every month during spring and summer. High - Apply every month during winter and twice each month during the spring and summer.