Surjit Patar: Poet of the Personal and the Political

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dated : 23/4/2016

Dated : 23/4/2016 Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name Defaulting Year 01750017 DUA INDRAPAL MEHERDEEP U72200MH2008PTC184785 ALFA-I BPO SERVICES 2009-10 PRIVATE LIMITED 01750020 ARAVIND MYLSWAMY U01120TZ2008PTC014531 M J A AGRO FARMS PRIVATE 2008-09, 2009-10 LIMITED 01750025 GOYAL HEMA U18263DL1989PLC037514 LEISURE WEAR EXPORTS 2007-08 LTD. 01750030 MYLSWAMY VIGNESH U01120TZ2008PTC014532 M J V AGRO FARM PRIVATE 2008-09, 2009-10 LIMITED 01750033 HARAGADDE KUMAR U74910KA2007PTC043849 HAVEY PLACEMENT AND IT 2008-09, 2009-10 SHARATH VENKATESH SOLUTIONS (INDIA) PRIVATE 01750063 BHUPINDER DUA KAUR U72200MH2008PTC184785 ALFA-I BPO SERVICES 2009-10 PRIVATE LIMITED 01750107 GOYAL VEENA U18263DL1989PLC037514 LEISURE WEAR EXPORTS 2007-08 LTD. 01750125 ANEES SAAD U55101KA2004PTC034189 RAHMANIA HOTELS 2009-10 PRIVATE LIMITED 01750125 ANEES SAAD U15400KA2007PTC044380 FRESCO FOODS PRIVATE 2008-09, 2009-10 LIMITED 01750188 DUA INDRAPAL SINGH U72200MH2008PTC184785 ALFA-I BPO SERVICES 2009-10 PRIVATE LIMITED 01750202 KUMAR SHILENDRA U45400UP2007PTC034093 ASHOK THEKEDAR PRIVATE 2008-09, 2009-10 LIMITED 01750208 BANKTESHWAR SINGH U14101MP2004PTC016348 PASHUPATI MARBLES 2009-10 PRIVATE LIMITED 01750212 BIAPPU MADHU SREEVANI U74900TG2008PTC060703 SCALAR ENTERPRISES 2009-10 PRIVATE LIMITED 01750259 GANGAVARAM REDDY U45209TG2007PTC055883 S.K.R. INFRASTRUCTURE 2008-09, 2009-10 SUNEETHA AND PROJECTS PRIVATE 01750272 MUTHYALA RAMANA U51900TG2007PTC055758 NAGRAMAK IMPORTS AND 2008-09, 2009-10 EXPORTS PRIVATE LIMITED 01750286 DUA GAGAN NARAYAN U74120DL2007PTC169008 -

Alumni Membership List 2020

Punjabi University Alumni Association Membership List M.No Title Name Present Position/ Degree/Year of Joining & Address D.O.B. P. No. (R), (O), (M) E-Mail Address Occupation Year of Leaving 1 Dr Jaspal Singh Ex. Vice-Chancellor M.A. Pol. Sci., Diploma in foreign Punjabi University, Patiala affairs (stood first), Ph.D. Patron Members M.No Title Name Present Position/ Degree/Year of Joining & Address D.O.B. P. No. (R), (O), (M) E-Mail Address Occupation Year of Leaving 2 Sh Gurcharan Singh Virk Excise & Taxation M.A Eng, P.G. Dip. in # 1552, Sector 36-D, Chandigarh 04-11-47 0172-2602739, 01763- Officer Lingustics/1967-1970 232183, 98143-02391 Life Members M.No Title Name Present Position/ Degree/Year of Joining & Address D.O.B. P. No. (R), (O), (M) E-Mail Address Occupation Year of Leaving 994 M/s Ravneet Kaur Smagh Zoology Model Town, Phase-II, Bathinda 0164-3292458, 9780495292 [email protected] 1081 Sh Charan Gill Punjabi Deptt. 94-C, Professor colony, Patiala 2280006 [email protected] 328 Sh. Raminderjit Singh Wasu Sub-Editor LL.B, M.J.M.C/1990-1992 # 1158-59/3, Chhoti Barandari, Beat 01-01-1969 (R) 0175-2201195 (O) 0172- 8, Patiala. 2655062, 98155-51482 617 Sh Ajit Pal Singh Lecturer M.A./Pol. Sci./2003-2005 H.No. B-XIII/1096, Nanaksar bye 01-01-82 01679235047, 9988042733 ;pass road, Barnala, Distt. Sangrur 669 Mrs Manisha Bansal M.Sc./Chemistry 44, Mansahia Colony, 21 No. Phatak, 01-01-79 2227741 [email protected] Patiala 840 Sh Jaspreet Singh M.P.Ed VPO Bahadurgarh, Dist. -

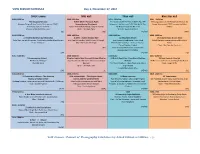

VOW SESSION SCHEDULE Day 1, November 17, 2017

VOW SESSION SCHEDULE Day 1, November 17, 2017 ONGC Lawns SREI Hall Titan Hall Blue Star Hall 1000-1130 hrs 1200-1315 hrs 1215 - 1315 hrs 1245 -1300 hrs The Inaugural Session 7.With Malice Towards None: 11.Launch of the RST Forum by PD Rai, MP 16.Inauguration of the Philately exhibition by Naveen Chopra,Robin Gupta,CS,Governor,CPMG, Remembering Khushwant Release of the Book on Dr RS Tolia by SK Das, Suneel Advani and CPMG curated by Abhai Gurcharan Das,H.P.Kanoria Harish Trivedi/Rahul Singh/ /Syeda Hamid NS Naplachayal and BK Joshi Mishra Release of the First Day cover Chair : Sir Mark Tully Tributes by Well Wishers (SC) (RG) (PT/KR) (RNR) 1140-1250 hrs 1500-1600 hrs 1340-1500 hrs 1300-1400 hrs 1. Hindi Ka Vartman Aur Bhavishya 8.1971 : India's Decisive War 12.Mountain Echoes 17.Victoria Cross: A Love Story Rahul Dev, Suresh Rituparna, Alok Mehta,Baldev Bhai Sharma Maj Gen AJS Sandhu, VSM/Lt Gen TS Shergil, The Changing Landscape : Anup Shah Ashali Verma in conversation with Col DPK Chair : LS Bajpai Maj Gen Shamsher Singh The Decadal Journeys - Askot to Arakot : Pillay Pahar/Shekhar Pathak Chair : Maj Gen Ian Cardozo (AS) State of Indian Mountains: Sustainable Development /IMI/SDFU (DP) (PT/KR) (AS) 1315 -1400 hrs 1330 -1430 hrs 1500-1545 1415-1500 hrs 2.Remembering Shivani 9.Indira: India’s Most Powerful Prime Minister 13.Asia ki Peeth Par : Uma Bhatt/Shekhar 18.Book Launch : One Life IRA Pande ,LS Bajpai Sagarika Ghose with Satish Sharma and Anjali Pathak) PK Basu in conversation with Nagendra Kumar Chair:BK Joshi Nauriyal The Pundit Brothers –Nain Singh and Kishen Chair : Swpn Dutta Chair : Sir Mark Tully Singh Rawat Curated by Lokesh Ohri (DP) SC (PT/KR) (SC) 1410-1515 hrs 1615-1715 hrs 1600-1645 1515 -1615 hrs 3. -

Gauri Gill 1984, a Bibliography a Adam Jones, Genocide: A

Gauri Gill 1984, A Bibliography A Adam Jones, Genocide: A Comprehensive Introduction, Routledge Press (ISBN 9781317533856), 2016 Aatish Taseer, The Way Things Were,Pan Macmillan (ISBN 9789382616337), 2014 A.G. Noorani, CIVIL LIBERTIES: Supreme Court and Punjab Crisis, EPW magazine, September 22, 1984 A.G. Noorani, CIVIL LIBERTIES: Rule of Law and Terrorism in Punjab and Northern Ireland, EPW magazine, October 20, 1984 A.G. Noorani, CIVIL LIBERTIES: Ill-Treatment of Political Detenus, EPW magazine, April 20, 1985 A.G. Noorani, CIVIL LIBERTIES: The Terrorist Act, EPW magazine, June 1, 1985 A.G. Noorani, Misra commission under fire, Sikh Review, 35 (401), May 1987 A.G. Noorani, CIVIL LIBERTIES: Repressive Laws in Punjab, EPW magazine, September 12, 1987 A.G. Noorani, CIVIL LIBERTIES: Ill-Treatment of Political Detenus, EPW magazine, January 23, 1988 A.G. Noorani, Crisis in Judiciary, Frontline, May 11, 2018 Ajaz Ashraf, 1984 revisited: The guilty men of Delhi, Sikh Review, 41 (11), November 1993 Ajeet Caur, November Churasi (Short story collection), Navyug Publishers, 1995 Ajmer Singh, Etmad A. Khan, Carnage 84, The Ambushing Of Witnesses, Tehelka magazine Special Issue October 8, 2005 Amandeep Sandhu, Roll of Honour, Rupa Publications, (ISBN 9788129120236), 2013 Amarjit Chandan, Jugni (Essay), Likhat Parhat, Navyug Publishers, 2013 Amarjit Chandan, Punjab de QatilãN' nu and O jo huNdey sann (Poems), JarhãN, 1995, 1999, 2005 Amarjit Chandan, The Camera and 1984, https://sikhchic.com/1984/the_camera_1984, 2012 Amitav Ghosh, The Ghosts of Mrs Gandhi, The New Yorker magazine, July 1995 Amiya Rao, When Delhi Burnt, EPW magazine, December 8, 1984 Amiya Rao, The Delhi massacre and censoring the Sikhs. -

Computer Science

Computer Science 003.3 H258M Hardeep Singh Modelling and design of software metrics for object oriented systems, 2003. 108p. Dept. Comp.Sc.& Engg. 15273 Supvr. Surjit Singh 003.5 P255M Parminder Kaur A model for versioning control mechanism in component based systems, 2010. 261p. Dept. Comp.Sc.& Engg. 16171 Supvr. Hardeep Singh 004.16 S271D Sawhney, B.K. Devolopment of microprocessor based dedicated multiterminal component test equipment, 1996. 173p. Dept. E.T. 1871 Supvr. Sohal, J.S. 004.2 P276A Parvinder Singh Automatic evaluation of domain specific components using neurofuzzy approach, 2007. 122p. Dept. Comp.Sc.& Engg. 15809 Supvr. Hardeep Singh 004.21 S531A Sharma, Lalitsen Analysis, design and development of re-applicable and re-usable models of electronic governance, 2006. 324p. Dept. Comp.Sc.& Engg. 15898 Supvr. Surjit Singh 004.3 S965A Sushil Kumar A measurement framework for aspect oriented software testability, 2012. 115p. Dept. Comp.Sc.& Engg. 16630 Supvr. Kahlon, K.S. 1 004.35 G977P Gupta, O.P. Performance characterization of networked machines as a parallel system, 2007. 187p. Dept. Comp.Sc.& Engg. 15725 Supvr. Kahlon, Karanjeet Singh 004.35 S531O Sharma, Sandeep On a class of multistage interconnection networks in parrallel processing, 2010. 194p. Dept. Comp.Sc.& Engg. 16172 Supvr. Kahlon, Karanjeet Singh 004.54 K12V Kahlon, Karanjeet Singh Virtual parallel computer using Web servers and servelets, 2003. 181p. Dept. Comp.Sc.& Engg. 15362 Supvr. Surjit Singh 004.6 K11E Kakkar, Ajay Efficient key mechanisms in multinode network for secured data transmission, 2012. 176p. Dept. E.T. 16672 Supvr. M.L. Singh 16673 004.6 R197U Rajeev Kumar Use of Internet resources and services in the engineering colleges of Punjab, Haryana and Himachal Pardesh: a survey, 2005. -

S.C.D. Govt. College Ludhiana 141001

S.C.D. Govt. College Ludhiana 141001 SELF STUDY REPORT (SSR) Submitted to NAAC National Assessment and Accreditation Council P.O Box No. 1075, Nagarbhavi, Bangalore- 560072 Submitted by: S.C.D. Govt. College Ludhiana www.scdgovtcollege.org E-mail- [email protected] Phone- (M) +919815963379 (O) 0161-2448899 SSR Report- 2015 of S.C.D Govt. College, Ludhiana (141001) Page 1 SSR Report- 2015 of S.C.D Govt. College, Ludhiana (141001) Page 2 SSR Report- 2015 of S.C.D Govt. College, Ludhiana (141001) Page 3 SSR Report- 2015 of S.C.D Govt. College, Ludhiana (141001) Page 4 INDEX Part- I Profile of the College- 6-17 Part- II Criterion I- 18-48 Criterion II- 49-83 Criterion III- 84-117 Criterion IV- 118-133 Criterion V- 134-161 Criterion VI- 162-187 Criterion VII- 188-202 Part- III Departmental Evaluation Report- 203-404 Executive Summary- 405-415 SSR Report- 2015 of S.C.D Govt. College, Ludhiana (141001) Page 5 Profile of the Affiliated / Constituent College 1. Name and Address of the College- Name- S.C.D. Government College, Ludhiana Address- College Road, Civil Lines, Ludhiana City- Pin- 141001 State- Punjab Website- www.scdgovtcollege.org 2. For Communication- Designation Name Telephone Mobile Fax Email with STD code Principal Mr. D.S. O-0161-2448899 - - [email protected] Sandhu R-9815963379 Vice Principal Mr. R.K. O-0161-2448899 - - [email protected] Miglani R-9815787900 Steering Dr. Ashwani O-0161-2448899 - - [email protected] Committee Kumar Bhalla R-9478020043 Co-ordinator 3. Status of the Institution- Affiliated College - Yes Constituent College Any other (specify) 4. -

E-Newsletter

DELHI hhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhh a large number of languages in India, and we have lots BHASHA SAMMAN of literature in those languages. Akademi is taking April 25, 2017, Vijayawada more responsibility to publish valuable literature in all languages. After that he presented Bhasha Samman to Sri Nagalla Guruprasadarao, Prof. T.R Damodaran and Smt. T.S Saroja Sundararajan. Later the Awardees responded. Sri Nagalla Guruprasadarao expressed his gratitude towards the Akademi for the presentation of the Bhasha Samman. He said that among the old poets Mahakavai Tikkana is his favourite. In his writings one can see the panoramic picture of Telugu Language both in usage and expression. He expressed his thanks to Sivalenka Sambhu Prasad and Narla Venkateswararao for their encouragement. Prof. Damodaran briefed the gathering about the Sourashtra dialect, how it migrated from Gujarat to Tamil Nadu and how the Recipients of Bhasha Samman with the President and Secretary of Sahitya Akademi cultural of the dialect has survived thousands of years. He expressed his gratitude to Sahitya Akademi for Sahitya Akademi organised the presentation of Bhasha honouring his mother tongue, Sourashtra. He said Samman on April 25, 2017 at Siddhartha College of that the Ramayana, Jayadeva Ashtapathi, Bhagavath Arts and Science, Siddhartha Nagar, Vijayawada, Geetha and several books were translated into Andhra Pradesh. Sahitya Akademi felt that in a Sourashtra. Smt. T.S. Saroja Sundararajan expressed multilingual country like India, it was necessary to her happiness at being felicitated as Sourashtrian. She extend its activities beyond the recognized languages talked about the evaluation of Sourashtra language by promoting literary activities like creativity and and literature. -

Culture of Punjab Test

CULTURE OF PUNJAB TEST Q 1. Which one of the following is considered as'Taxali Boli'? A. Majhi B. Malvai C. Doabi D. Puadhi Q 2. Which one of the following dialect of punjabi is used in the areas falling between Beas and the Satluj? A. Malvai B. Doabi C. Puadhi D. Majhi Q 3. Who amongst the following acted as a scribe to write 'Adi Granth'? A. Bhai Bhudha ji B. Bhai Gurdas ji C. Bhai Mardanaji D. None of above Q 4. Who amongst the following is considered as the Pioneer of the Kafi form Punjabi poetry? A. Shah Hussain B. Bulleh Shah C. Waris Shah D. Pillu Q 5. Who amongst the following is honoured as the Shakespeare of Punjab? A. Bulleh Shah B. Waris Shah C. Shah Hussain D. None of above Q 6. WHo amongst the following is considered as the creator of Modern Punjabi literature? A Bhai Kahn Singh Nabha B. Dliani Ram, Chatrik C. Bhai Vir Singh D. Sant Singh Sekhon Q 7, Who amongst the following is known as the'Father of Punjabi Dram'? A. Sant Singh Sekhon B. Balwant Gargi C. Gurdial Singh D. Ishwar Chandra Nanda Q 8.'Chitta Lahu' and'Ikk Mian do Talwara' are the compositions of. A. Balwant Gargi B. Nanak Singh C. Bhai Vir Singh D. Ishwar Chandra Nanda Q 9.'The Naked Triangle'is an autobiography of whom of the following? A. Balraj Sahni B. Balwant Gargi C. Jaswant Singh Kanwal D. Karlar Singh Duggal Q 10. Amrita Pritam received Bhartiya Jnanpith Award for which one of her compositions? A. -

(A Collection of ICSE Poems & Short Stories) (Inter Univer

Appendix - I INDIAN CERTIFICATE OF SECONDARY EDUCATION EXAMINATION, MARCH 2018 LIST OF PRESCRIBED TEXTBOOKS 1. ENGLISH (01): 5) God lives in the Panch – Munshi Premchand PAPER 1. (Language) 6) The Last Leaf - O’ Henry No specific book is being recommended for 7) Kabuliwala - Rabindranath Tagore background reading. 8) The Bet - Anton Chekov 9) The Tiger in the Tunnel - Ruskin PAPER 2. (Literature in English) Bond DRAMA: The Merchant of Venice 10) Princess September - W. Somerset (Shakespeare’s unabridged play by A.W. Maugham Verity) (ii) Animal Farm: George Orwell OR (iii) To Sir with Love: E.R. Braithwaite Loyalties: John Galsworthy (Edited by G.R. Hunter) INDIAN LANGUAGES: (A collection of ICSE Poems & Short 2. AO NAGA (42): Stories) (Inter University Press) (At least two of the following books are to be offered) POETRY: (All poems to be studied) (i) Mejen O 2nd edition. 1) Where the mind is without fear – Rabindranath Tagore (An Anthology of Poems and Short Stories by Contemporary Ao writers, JMS 2) The Inchcape Rock – Robert Publication). Southey nd 3) In The Bazaars of Hyderabad – (ii) Khristan Aeni Aoba 2 edition. Sarojini Naidu (A translation of John Bunyan’s 4) Small Pain in my chest – Michael ‘The Pilgrim’s Progress’, ABAM Mack Publication). 5) The Professor – Nissim Ezekiel (iii) Akumlir Wadang by L. Imti Aier. 6) Stopping by woods on a snowy 3. ASSAMESE (02): evening – Robert Frost (At least two of the following books are to be 7) A Doctor’s journal entry for offered) August 6, 1945 – Vikram Seth (i) Karengar Ligiri (Drama): by Jyoti Prasad 8) If thou must love me…. -

List of Faculty Publications 2012

JAWAHARLAL NEHRU UNIVERSITY LIST OF FACULTY PUBLICATIONS 2012 Compiled by Mahesh Chand, Assistant Librarian Amar Singh Yadav, Professional Assistant DR. B. R. AMBEDKAR CENTRAL LIBRARY 2012 1 Part - A FACULTY PUBLICATIONS SCHOOL OF ARTS AND AESTHETICS AHUJA, NAMAN P. 1. InFlux: contemporary art in Asia. New Delhi: SAGE Publications, 2012. 2. Ramkinar through the eyes of Devi Prasad. New Delhi: School of Arts & Aesthetics, Jawaharlal Nehru University, 2007. 3. The making of a modern Indian artist-craftsman Devi Prasad. New Delhi: Rutledge India, 2011. DUTT, BISHNUPRIYA 4. Engendering performance: Indian women performers in search of an identity. New Delhi: Sage Pub. 2010. JAIN, JYOTINDRA 5. Art and Rituals: 2500 Years of Jainism in India. New Delhi: Sterling Publishers, 1977. 6. Francesco Clemente: Made in India. New York: Charta Publisher, 2011. 7. Ganga Devi: traditions and Expressions in Mithila Painting. Ahmedabad: Mapin Publishing, 1997. 8. India's Popular Culture: Iconic Spaces and Fluid Images. Mumbai, Marg Pub., 2007. 9. Indian Popular Culture, the Conquest of the World as Picture. New Delhi: Ajeepay Press, 2004. 10. Indian Terracotta . Mumbai: India Book House, 2003. 11. Jaina Iconography 1. the T?rthankara in Jaina Sculptures, Art and Rituals. Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers, 1978. 12. Kalighat painting: images from a changing world. Ahmedabad: Mapin Pub, 1999. 13. National Handicrafts and Handlooms Museum, New Delhi. Mumbai: Mapin Publishing, 2003. 2 14. Picture Snowmen: Insights into the Narrative Tradition in Indian Art. Mumbai: Marg Publications, 1998. 15. Raj Rewals- Library For Indian Parliament. New Delhi: Roli Books, 2011. 16. Tempeltucher Fur Die Muttergottinnen in Indien: Zeremonien, Herstellung Und Ikonographie Gemalter Und Gedruckter Stoffbilder Aus Gujarat. -

National Sanskrit Book Fair at Varanasi

Annual Subscription Rs 5.00; 50 paise per copy October 2017 • Vol 35 No. 10 Contents National Sanskrit Book Fair at Varanasi Sanskrit Advisory Panel Meeting 2 Hindi Pakhwada Celebrations 3 Indonesia International Book Fair 4 Gura Sangraha 5 Tiruvannamalai Book Fair 5 Foundation Day Celebrations at Hyderabad BPC 5 NBT Activities in Punjab 6 Training Courses in Book Publishing 6 Today is the golden day for Sanskrit as Sanskrit is the language which expresses “the first ever Sanskrit Book Fair is being thoughts in very few words. Books On and By Gandhi organized by the National Book Trust, While welcoming the guests, Shri 7 India in the country,” said Shri Ram Naik, Baldeo Bhai Sharma, Chairman, NBT PICK OF THE MONTH Hon’ble Governor of Uttar Pradesh while said that Varanasi has had been the inaugurating National Sanskrit Book Fair centre of knowledge and has spread on 9 September 2017. The book fair was knowledge across the world. He expressed organized at Town Hall, Varanasi from 9 his happiness that the first ever Sanskrit to 17 September 2017. Shri Ram Naik Book Fair is being organized by the Trust further added that this effort by the Trust in Varanasi. Besides, he also talked about to promote Sanskrit is commendable as the book promotion activities of the Concept of Zero S P Deshpande 978-81-237-8048-6; Rs 125 OCTOBER 2017 NBT NEWSLETTER 1 Trust. He added that the Trust has been of the heritage of Sanskrit language, and working towards the promotion of Indian philosophic texts in nation building, languages and in this context, it has also and the basic inspiration that they have initiated publication and promotion of provided to the national institutions as Sanskrit books. -

Procedures and Policies for Maintaining and Utilizing Physical, Academic and Support Facilities - Laboratory, Library, Sports Complex, Computers, Classrooms Etc

Procedures and policies for maintaining and utilizing physical, academic and support facilities - laboratory, library, sports complex, computers, classrooms etc. Sambalpur University has a University Scientific Instrumentation Centre (USIC), headed by a Professor –in- Charge and run by technical staff. It provides effective and economical services in the repair and maintenance of scientific/ electronic instruments of various laboratories and electrical appliances of academic as well as administrative units. The objectives of this facility are to provide maintenance service to all the sophisticated instruments housed in various departments, and to fabricate instruments and accessories for research purpose. The facilities as shown in following table are available to the faculty members and research scholars. In addition to this USIC takes care of all the electrical maintenance work of the University which includes office, Department, Hostel and residential quarter. The University has a Development and Maintenance Section and University Scientific Instrumentation Center (USIC) to look after the maintenance of buildings, classrooms and laboratories. The infrastructure facilities and services are maintained by the technical personnel such as Asst. Engineer and Junior Engineer, who work under the supervision of the Development Officer. Networking, computers and accessories are managed and maintained by the E-Governance Nodal Centre under AMC. The AMC vendor is stationed on the campus having two dedicated engineers to resolve technical issues. Internet 1 GB link under NMEICT/NKN and its services are completely maintained and managed by the expertise of computer centre in-house. BEST PRACTICE BEST PRACTICE- 1: Award of the “Gangadhar National Award for Poetry” to the poets of all-India stature Objectives of the Practice: Sambalpur University believes that promotion of art and culture is as important as the production of theoretical and applied knowledge in the pursuit of its humanist mission.