Cell Free (Cf)DNA Screening for Down Syndrome in Multiple Pregnancies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

For the Common Man Chicago Sinfonietta Paul Freeman, Music Director and Conductor Harvey Felder, Guest Conductor

Sunday, October 3, 2010, 2:30 pm – Dominican University Monday, October 4, 2010, 7:30 pm – Symphony Center For the Common Man Chicago Sinfonietta Paul Freeman, Music Director and Conductor Harvey Felder, Guest Conductor Fanfare for the Common Man ............................................................................Aaron Copland Neue slavische Tänze (Slavonic Dances), op.72 no.7 (15) ........................Antonín Dvořák 7. In C major - SrbskÈ Kolo Fire and Blood, for Violin and Orchestra .............................................. Michael Daugherty 1. Volcano 2. River Rouge 3. Assembly Line Tai Murray, violin Intermission Sundown’s Promise (for Taiko and Orchestra) ................................................. Renée Baker I. Company Song VII. Transcendence II. Wa ( peace/balance) VIII. No Mi Kai (Drinking party) III. Wabi IX. Chant IV. Sabi X. Sitting V. Pride XI. Walking VI. Enkai (Banquet Feast) XII. Learning to see the Invisible XIII. Shime (Ending of celebration) JASC Tsukasa Taiko, Japanese drums and Shamisen Nicole LeGette, butoh dancer On the Waterfront: Symphonic Suite from the Film ............................ Leonard Bernstein Lead Season Sponsor Lead Media Sponsor Sponsors Bettiann Gardner Please hold your applause for a brief silence after each work. This will help everyone to enjoy every note. chicagosinfonietta.org facebook.com/chicagosinfonietta Chicago Sinfonietta 1 THE MAESTRO’S FINAL SEASON These 2010 season-opening performances mark the beginning of a season of transition as our beloved Founder and Music Director Paul Freeman takes the podium for the final time. Throughout the year Maestro Freeman will be conduct- ing pieces that have become personal favorites of his, many of which he probably introduced to you, our audience. We will also be sharing some of his compelling life story and reprinting some amazing photos from the Sinfonietta archive. -

The Genetic Heterogeneity of Brachydactyly Type A1: Identifying the Molecular Pathways

The genetic heterogeneity of brachydactyly type A1: Identifying the molecular pathways Lemuel Jean Racacho Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Postdoctoral Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctorate in Philosophy degree in Biochemistry Specialization in Human and Molecular Genetics Department of Biochemistry, Microbiology and Immunology Faculty of Medicine University of Ottawa © Lemuel Jean Racacho, Ottawa, Canada, 2015 Abstract Brachydactyly type A1 (BDA1) is a rare autosomal dominant trait characterized by the shortening of the middle phalanges of digits 2-5 and of the proximal phalange of digit 1 in both hands and feet. Many of the brachymesophalangies including BDA1 have been associated with genetic perturbations along the BMP-SMAD signaling pathway. The goal of this thesis is to identify the molecular pathways that are associated with the BDA1 phenotype through the genetic assessment of BDA1-affected families. We identified four missense mutations that are clustered with other reported BDA1 mutations in the central region of the N-terminal signaling peptide of IHH. We also identified a missense mutation in GDF5 cosegregating with a semi-dominant form of BDA1. In two families we reported two novel BDA1-associated sequence variants in BMPR1B, the gene which codes for the receptor of GDF5. In 2002, we reported a BDA1 trait linked to chromosome 5p13.3 in a Canadian kindred (BDA1B; MIM %607004) but we did not discover a BDA1-causal variant in any of the protein coding genes within the 2.8 Mb critical region. To provide a higher sensitivity of detection, we performed a targeted enrichment of the BDA1B locus followed by high-throughput sequencing. -

Dynamic Modification Strategy of the Israeli Carrier Screening Protocol: Inclusion of the Oriental Jewish Group to the Cystic Fibrosis Panel Orit Reish, MD1,2, Zvi U

ARTICLE Dynamic modification strategy of the Israeli carrier screening protocol: inclusion of the Oriental Jewish Group to the cystic fibrosis panel Orit Reish, MD1,2, Zvi U. Borochowitz, MD3, Vardit Adir, PhD3, Mordechai Shohat, MD2,4, Mazal Karpati, PhD2,5, Atalia Shtorch, PhD6, Avi Orr-Urtreger, MD, PhD2,7, Yuval Yaron, MD2,7, Stavit Shalev, MD8, Fuad Fares, PhD9, Ruth Gershoni-Baruch, MD10, Tzipora C. Falik-Zaccai, MD11, and Daphne Chapman-Shimshoni, PhD1 Purpose: A retrospective population study was conducted to determine he different Jewish ethnic groups were isolated from the surrounding non-Jewish populations as a result of religious the carrier frequencies of recently identified mutations in Oriental T restrictions and cultural differences, and from each other by Jewish cystic fibrosis patients. Methods: Data were collected from 10 geographical boundaries.1–3 Thus, their respective genetic loads medical centers that screened the following mutations: two splice site differ, except for more ancient founder mutations common in all Ͼ ϩ mutations—3121-1G A and 2751 1insT—and one nonsense muta- Jews that were acquired before the communities dispersed.2 tion—the Y1092X in Iraqi Jews. One missense mutation, I1234V, was With the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948, many of screened in Yemenite Jews. Results: A total of 2499 Iraqi Jews were these Jews migrated back to Israel. Both the mutations charac- tested for one, two, or all three mutations. The 3121-1GϾA, Y1092X, teristic to the specific ethnic groups and the common Jewish and 2751 ϩ 1insT mutations had a carrier frequency of 1:68.5, 1:435, mutations created the basis for the ethnic-specific screens of- and 0, respectively. -

Viola Da Gamba

C01PAC.T Studio One and has made radio and television appearances in the U.S., Spain, .1IW University of Washington D\Sc.. Costa Rica, and Korea. THE SCHOOL OF MUSIC As co-founder of the Corigliano Quartet, Lim has won numerous awards. W:;, including the Grand Prize at the Fischoff Chamber Music Competition and the Presents a Debut Faculty Recital: TO--', ASCAP/CMA Award for Adventurous Programming. The Corigliano Quartet OD maintains an active performing schedule. having appeared at such venues as 1 t '1 Carnegie Hall, Weill Recital Hall, Alice Tully Hall and the Kennedy Center. Lim has also performed as concertmaster of the Hartford Symphony Orchestra and the Evansville Philharmonic, and currently holds a position at the Metro politan Opera House as a member of the American Ballet Theatre Orchestra, in o~ which he has performed as Assistant Concertmaster. MELIA Lim's violin teachers have included his mother, Sun Boo Lim, Vartan Manoogian, Josef Gingold, Mauricio Fuks and Yuval Yaron. He received ~ bachelor's and master's degrees from Indiana University, where he won first prize in the school's Violin Concerto Competition. Lim served on the faculty at Indiana as a visiting lecturer and later taught chamber music at the Juilliard WATRAS, School as an assistant to the Juilliard String Quartet. He has also served as musical artist in residence at Dickinson College and on the faculty of the New York Youth Symphony Chamber Music Program. viola RICHARD KARPEN (b. 1957, New York) is Director of The Center for Digital Arts ang Experimental Ms-:dia (RXARTS) at the :U;niversity of Washington in Seattle. -

Thursday • April 10 • 2014 Welcome to U-Nite

THURSDAY • APRIL 10 • 2014 WELCOME TO U-NITE Make yourself at home at the third annual U-Nite celebration of arts, artists, community, creativity, and education. The Crocker and Sac State, two of the region’s leading educational institutions, are the perfect combination for serving up another blockbuster celebration of the arts. The talented faculty (and students!) in the College of Arts and Letters at Sacramento State will be featured at the Crocker, a world-class venue and community convener. Enjoy this electric celebration and drink in the art. It’s good for you. Better than kombucha. Take it all in! Welcome to U-Nite! — Elaine Gale, U-Nite Founder and Associate Professor of Communication Studies and Journalism, Sacramento State Welcome to U-Nite at the Crocker! This is our celebration of creativity, partnership, and community that showcases the incredible talent of Sacramento State’s students, faculty, and staff. Our partnership with the Crocker Art Museum offers a powerful venue that inspires creativity and allows for our community to gather and share in the rich creative and cultural gifts our city and region offer. Enjoy your evening; we appreciate you being here. — Edward S. Inch, Dean, College of Arts & Letters, Sacramento State Co-coordinators Lorelei Bayne Elaine Gale RIka Nelson Vice Chair, Department of Associate Professor Manager, Public Programs, Theatre and Dance of Communication Crocker Art Museum Associate Professor, Dance, Studies and Journalism, Sacramento State Sacramento State Thanks to the Mort and Marcy Friedman Director, Lial A. Jones, Crocker Art Museum; President Alexander Gonzalez, Sacramento State; Provost Frederika Harmsen, Sacramento State; Dean Edward Inch, Sacramento State; and the artists, educators and staff of the Crocker Art Museum and Sacramento State’s College of Arts and Letters. -

Ethnic Effect on FMR1 Carrier Rate and AGG Repeat Interruptions Among Ashkenazi Women

ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE © American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics Ethnic effect on FMR1 carrier rate and AGG repeat interruptions among Ashkenazi women Karin Weiss, MD1, Avi Orr-Urtreger, MD, PhD1,2, Idit Kaplan Ber, PhD1, Tova Naiman, MA1, Ruth Shomrat, PhD1, Eyal Bardugu, BA1, Yuval Yaron, MD1,2, and Shay Ben-Shachar, MD1 Purpose: Fragile X syndrome, a common cause of intellectual dis- frequency of other peaks (P < 0.0001). A higher rate of premutations ability, is usually caused by CGG trinucleotide expansion in the in the 55–59 repeats range (1:114 vs. 1:277) was detected among the FMR1 gene. CGG repeat size correlates with expansion risk. Pre- Ashkenazi women. Loss of AGG interruptions (<2) was significantly mutation alleles (55–200 repeats) may expand to full mutations in less common among Ashkenazi women (9 vs. 19.5% for non-Ashke- female meiosis. Interspersed AGG repeats decrease allele instability nazi women, P = 0.0002). and expansion risk. The carrier rate and stability of FMR1 alleles were Conclusion: Ashkenazi women have a high fragile X syndrome car- evaluated in large cohorts of Ashkenazi and non-Ashkenazi women. rier rate and mostly lower-range premutations, and carry a low risk Methods: A total of 4,344 Ashkenazi and 4,985 non-Ashkenazi for expansion to a full mutation. Normal-sized alleles in Ashkenazi cases were analyzed using Southern blotting and polymerase chain women have higher average number of AGG interruptions that may reaction between 2004 and 2011. In addition, AGG interruptions increase stability. These factors may decrease the risk for fragile X were evaluated in 326 Ashkenazi and 298 non-Ashkenazi women syndrome offspring among Ashkenazi women. -

Cuarteto Latinoamericano Dalí Quartet

CUARTETO LATINOAMERICANO DALÍ QUARTET May 13, 2013 7:00 PM Americas Society 680 Park Avenue, New York, NY WELCOME Dear friends, Welcome to the first concert in our Iconic and Emerging Artists series, which includes this week’s literary symposium and continues throughout the 13/14 Music of the Americas season with performances in various musical styles. These concerts will highlight the fundamental process of artistic transmission by which musical traditions are shared and continued. Tonight we are delighted to welcome back to our stage the Cuarteto Latinoamericano in a collaboration with the young Dalí Quartet. Tonight’s program offers a wide panorama of 20th century string music and includes Mignone’s Seresta, performed on the Latinoamericano’s Grammy-winning CD Brasileiro, arrangements of some of the greatest tango classics, and one of a handful of pieces for human instruments by Mexican maverick Conlon Nancarrow (most of his music is written for player piano). Thank you for joining us! Sebastian Zubieta, Music Director The MetLife Foundation Music of the Americas concert series is made possible by the generous support of Presenting Sponsor MetLife Foundation. This concert is supported by the National Endowment for the Arts and the Mexican Cultural Institute of New York. The Spring 2013 Music program is also supported, in part, by public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council. Additional support is provided by the Consulate General of Brazil in New York, and Clarion Music Society. In-kind support is graciously provided by the Bolivian-American Chamber of Commerce. -

International Violin Competition of Indianapolis

INTERNATIONAL VIOLIN COMPETITION OF INDIANAPOLIS International Violin Competition of Indianapolis 2013-2014 LAUREATE SERIES Indianapolis Power & Light Company Title Sponsor PLEASE NOTE: In consideration of our artists, no children under the age of six are admitted. No unauthorized photographic or recording equipment is allowed at the performances. Please turn off all sound devices including watches, cell phones and pagers. THANK YOU! International Violin Competition of Indianapolis 32 E. Washington Street, Suite 1320 Indianapolis, IN 46204 TEL: 317.637.4574 FAX: 317.637.1302 E-MAIL: [email protected] www.violin.org ARTS Indiana Arts Commission COUNCIL C&yxxifrtQ People to «*} Aiht OflNMAfWOUS ABOUT THE COMPETITION Remarkable performances, extraordinary prizes and a festival atmosphere characterize the International Violin Competition of Indianapolis [IVCI] as "the ultimate violin contest..." writes the Chicago Tribune. Laureates of "The Indianapolis" have emerged as outstanding artists in concert halls across the globe. For 17 days every four years, 40 of the world's brightest talents come here to perform some of the most beautiful music ever written before enthusiastic audiences in venues throughout the city including the Eugene and Marilyn Glick Indiana History Center, Christel DeHaan Fine Arts Center and Hilbert Circle Theatre, where finalists collaborate with the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra. Of the prizes awarded, perhaps the most astonishing is the loan of the 1683 ex-Gingold Stradivari violin, which is made available to one of the Laureates for the four years following the Competition. Under the guidance of Thomas J. Beczkiewicz, Founding Director, and the late Josef Gingold, who had served on the juries of every major violin competition in the world, the IVCI became known by the musical and media communities as one of the world's most compelling competitions. -

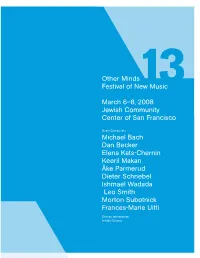

Other Minds 13 Program

Other Minds Festival of New Music March 6–8, 2008 Jewish Community Center of San Francisco Guest Composers Michael Bach Dan Becker Elena Kats-Chernin Keeril Makan Åke Parmerud Dieter Schnebel Ishmael Wadada Leo Smith Morton Subotnick Frances-Marie Uitti Charles Amirkhanian, Artistic Director 34 12 16 B 7 19 15 A 2 36 1 Other Minds, in association with the Djerassi Resident Artists Program and the Eugene and Elinor Friend Center for the Arts at the Jewish Community Center of San Francisco, presents Other Minds 13 Charles Amirkhanian, Artistic Director Jewish Community Center of San Francisco March 6-7-8, 2008 Table of Contents 3 Message from the Artistic Director 4 Exhibition & Silent Auction 6 Concert 1 7 Concert 1 Program Notes 10 Concert 2 11 Concert 2 Program Notes 14 Concert 3 15 Concert 3 Program Notes 20 Other Minds 13 Composers 24 About Other Minds Other Minds 13 Festival Staff 25 Other Minds 13 Performers 28 Festival Supporters A Gathering of Other Minds Program Design by Leigh Okies. Layout and editing by Adam Fong. © 2008 Other Minds. All Rights Reserved. The Djerassi Resident Artists Program is a proud co-sponsor of Other Minds Festival XIII The mission of the Djerassi Resident Artists Program is to support and enhance the creativity of artists by providing uninterrupted time for work, reflection, and collegial interaction in a setting of great natural beauty, and to preserve the land upon which the Program is situated. The Djerassi Program annually welcomes the Other Minds Festival composers for a five-day residency for collegial interaction and preparation prior to their concert performances in San Francisco. -

Sibelius (1865-1957, Finland)

SCANDINAVIAN, FINNISH & BALTIC CONCERTOS From the 19th Century to the Present A Discography of CDs and LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Jean Sibelius (1865-1957, Finland) Born in Hämeenlinna, Häme Province. Slated for a career in law, he left the University of Helsingfors (now Helsinki) to study music at the Helsingfors Conservatory (now the Sibelius Academy). His teachers were Martin Wegelius for composition and Mitrofan Vasiliev and Hermann Csilag. Sibelius continued his education in Berlin studying counterpoint and fugue with Albert Becker and in Vienna for composition and orchestration with Robert Fuchs and Karl Goldmark. He initially aimed at being a violin virtuoso but composition soon displaced that earlier ambition and he went on to take his place as one of the world's greatest composer who not only had fame in his own time but whose music lives on without any abatement. He composed a vast amount of music in various genres from opera to keyboard pieces, but his orchestral music, especially his Symphonies, Violin Concerto, Tone Poems and Suites, have made his name synonymous with Finnish music. Much speculation and literature revolves around Sibelius so-called "Symphony No. 8." Whether he actually wrote it and destroyed it or never wrote it all seems less important than the fact that no such work now exists. Violin Concerto in D minor, Op. 47 (1903-4, rev. 1905) Salvatore Accardo (violin)/Sir Colin Davis/London Symphony Orchestra ( + Dvorák: Violin Concerto) PHILIPS ELOQUENCE 468144-2 (2000) Salvatore Accardo (violin)/Sir Colin Davis/London Symphony Orchestra ( + 2 Humoresques and 4 Humoresques) AUSTRALIAN ELOQUENCE ELQ4825097 (2016) (original LP release: PHILIPS 9500 675) (1979 Salvatore Accardo (violin)/Mario Rossi/Orchestra Sinfonica di Torino della Radiotelevisione Italiana (rec. -

2018 Guide to Top Competitions

FEATURE ARTICLE Competition Insights from the Horse’s Mouth COMPETITIA Musical America Guide to Top CompetitionsONS February 2018 Editor’s Note Competitions: Necessary evil? Heart-breaking? Star-making? Life changing? Political football? Yes. And, controversial though they may be, competitions are increasing not only in number, but in scope. Among the many issues discussed in our interview with Benjamin Woodroffe, secretary general of the World Federation of International Music Competitions (WFIMC), some of the bigger competitions are not only choosing the best and the brightest, but also booking them, training them, and managing them. Woodroffe describes, for instance, the International Franz Liszt Competition in Utrecht, Netherlands, which offers its winners professional mentorship over a three-year period, covering everything from agent representation to media training to stagecraft to website production to contractual business training. A Musical America Guide to Top WFIMC, which is based in Switzerland, boasts a membership, mostly European, of 125 music competitions in 40 countries. Piano competitions prevail, at 33 percent of the total; up next are the multiple or alternating discipline events, followed by violin competitions. The fastest growing category is conducting. The primary requirement for COMPETITIONS membership in WFIMC is that your competition be international in scope—that applicants from all over the world are eligible to apply. The 2018 Guide to Music Competitions is our biggest to date, with 80 entries culled from the hundreds listed in our data base. (That’s up from the 53 with which we started this Guide, in 2015.) For each one, we listed everything from their Twitter handles to the names of the jury members, entry fees, prizes (including management, performances, and recordings, where applicable), deadlines, frequency, disciplines, semi-final and final dates, and eligibility. -

2016 - 2017 Season Boulder Chamber Orchestra

THE CURSE OF THE NINTH 13TH SEASON 2016 - 2017 Season Boulder Chamber Orchestra 9th. We call this The Curse of the 9th! Along the way, we will be collaborating Our jinx is Symphonies by various later composers, with a number of fantastic artists from near including Schubert and Bruckner, were and far, including Maestro Nicholas Carthy renumbered to put the best one last. Brahms as our first regular-season guest conductor your good and Mendelssohn didn’t even compose nine with the orchestra, the prize-winning symphonies, thus avoiding the Jinx! young violinist Yabing Tan, our favorite fortune... returning violinist Lindsay Deutsch, and Scholars believe that it took Brahms Boulder’s own Karen Bently Pollick. Intrigue A FEW KIND WORDS TO OUR between eighteen and twenty-one years will be added to the mix with the Boulder DEAR SUPPORTERS to compose his first symphony precisely premiere of the Beatles Suite for Violin and because he was terrified of being compared Orchestra by Maxime Goulet, and a brand- It’s been an exciting and challenging twelve to Beethoven and needed this extra time new Concerto for Violin and Orchestra seasons. As always, we’re grateful for to complete it to his own satisfaction. The by American composer David Jaffe. And your support, encouragement, and endless work contains a rather bold reference to the grand finale, Beethoven’s 9th, will be generosity, which have made the BCO what Beethoven’s Ode to Joy melody in the finale. performed in collaboration with the Boulder it is now. When one concertgoer remarked on this Chorale under the direction of resemblance at the symphony’s premiere, Vicki Burrichter.