Fort Yellowstone Other Name/Sit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moving Men and Supplies: Military Transportation on the Northern Great Plains, 1866-1891

Copyright © 1984 by the South Dakota State Historical Society. All Rights Reserved. Moving Men and Supplies: Military Transportation on the Northern Great Plains, 1866-1891 GARY S. FREEDOM Copyright © 1984 by the South Dakota State Historical Society. All Rights Reserved. Moving Men and Supplies 115 In the twenty-five years after the Civil War, the northern Great Plains was transformed from a frontier with limited trans- portation into a settled region with a complex transportation in- frastructure. In any assessment of this landscape modification, the military presence deserves consideration as an agent of change. In this period, 1866 to 1891, the army organized the terri- tories of Dakota and Montana into the Military Department of Dakota and established a network of forts that extended from the Red River to the Rockies and from the Canadian border to the Platte River (Figure 1). The isolation and vast distances between the individual forts on the northern Great Plains, and between this network and supply depots in the East, necessitated a com- plex transportation system to move men and materials. In order to facilitate these logistical operations, the military built a sys- tem of roads while protecting and utilizing established trails, waterways, and rail networks. Although the army had its own means of transport, for reasons of economy it preferred to em- 0 ver land freight wagons drawn by mules, 1885 Copyright © 1984 by the South Dakota State Historical Society. All Rights Reserved. 116 South Dakota History ploy civilian carriers to move men and supplies on a contractual basis. Various modes of commercial transportation were used, in- cluding freight wagons, stage coaches, riverboats, and railroads. -

History of Navigation on the Yellowstone River

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1950 History of navigation on the Yellowstone River John Gordon MacDonald The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation MacDonald, John Gordon, "History of navigation on the Yellowstone River" (1950). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 2565. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/2565 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HISTORY of NAVIGATION ON THE YELLOWoTGriE RIVER by John G, ^acUonald______ Ë.À., Jamestown College, 1937 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Mas ter of Arts. Montana State University 1950 Approved: Q cxajJL 0. Chaiinmaban of Board of Examiners auaue ocnool UMI Number: EP36086 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Ois8<irtatk>n PuUishing UMI EP36086 Published by ProQuest LLC (2012). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. -

Spawning and Early Life History of Mountain Whitefish in The

SPAWNING AND EARLY LIFE HISTORY OF MOUNTAIN WHITEFISH IN THE MADISON RIVER, MONTANA by Jan Katherine Boyer A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Fish and Wildlife Management MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY Bozeman, Montana January 2016 © COPYRIGHT by Jan Katherine Boyer 2016 All Rights Reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First, I thank my advisor, Dr. Christopher Guy, for challenging me and providing advice throughout every stage of this project. I also thank my committee members, Dr. Molly Webb and Dr. Tom McMahon, for guidance and suggestions which greatly improved this research. My field technicians Jordan Rowe, Greg Hill, and Patrick Luckenbill worked hard through fair weather and snowstorms to help me collect the data presented here. I also thank Travis Horton, Pat Clancey, Travis Lohrenz, Tim Weiss, Kevin Hughes, Rick Smaniatto, and Nick Pederson of Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks for field assistance and advice. Mariah Talbott, Leif Halvorson, and Eli Cureton of the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service assisted with field and lab work. Richard Lessner and Dave Brickner at the Madison River Foundation helped to secure funding for this project and conduct outreach in the Madison Valley. The Channels Ranch, Valley Garden Ranch, Sun West Ranch, and Galloup’s Slide Inn provided crucial land and river access. I also thank my fellow graduate students both for advice on project and class work and for being excellent people to spend time with. Ann Marie Reinhold, Mariah Mayfield, David Ritter, and Peter Brown were especially helpful during the early stages of this project. -

The Army Post on the Northern Plains, 1865-1885

The Army Post on the Northern Plains, 1865-1885 (Article begins on page 2 below.) This article is copyrighted by History Nebraska (formerly the Nebraska State Historical Society). You may download it for your personal use. For permission to re-use materials, or for photo ordering information, see: https://history.nebraska.gov/publications/re-use-nshs-materials Learn more about Nebraska History (and search articles) here: https://history.nebraska.gov/publications/nebraska-history-magazine History Nebraska members receive four issues of Nebraska History annually: https://history.nebraska.gov/get-involved/membership Full Citation: Ray H. Mattison, “The Army Post on the Northern Plains, 1865-1885,” Nebraska History 35 (1954): 17-43 Article Summary: Frontier garrisons played a significant role in the development of the West even though their military effectiveness has been questioned. The author describes daily life on the posts, which provided protection to the emigrants heading west and kept the roads open. Note: A list of military posts in the Northern Plains follows the article. Cataloging Information: Photographs / Images: map of Army posts in the Northern Plains states, 1860-1895; Fort Laramie c. 1884; Fort Totten, Dakota Territory, c. 1867 THE ARMY POST ON THE NORTHERN PLAINS, 1865-1885 BY RAY H. MATTISON HE opening of the Oregon Trail, together with the dis covery of gold in California and the cession of the TMexican Territory to the United States in 1848, re sulted in a great migration to the trans-Mississippi West. As a result, a new line of military posts was needed to guard the emigrant and supply trains as well as to furnish protection for the Overland Mail and the new settlements.1 The wiping out of Lt. -

DROUGHT RESILIENCE PLAN Jefferson River Watershed Council PO Box 550 Whitehall MT 59759

JEFFERSON RIVER WATERSHED DROUGHT RESILIENCE PLAN Jefferson River Watershed Council PO Box 550 Whitehall MT 59759 September 2019 Prepared for the Jefferson River water users as an educational guide to drought impacts, drought vulnerabilities and adaptation strategies to proactively plan for drought. Compiled by Evan Norman [email protected] Jefferson River Watershed Drought Resiliency Plan Contents Drought Resiliency ........................................................................................................................................ 2 Project Overview ....................................................................................................................................... 2 Drought Mitigation ................................................................................................................................... 4 Defining Drought ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Utilization of Resources for Defining Drought Resilience Efforts ............................................................. 6 Jefferson River Watershed Characteristics ................................................................................................... 7 Land and Soil Distribution ....................................................................................................................... 10 Agrimet – JVWM, Jefferson Valley, MT .................................................................................................. -

Montana GAR Posts & History

Grand Army of the Republic Posts - Historical Summary National GAR Records Program - Historical Summary of Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) Posts by State MONTANA Prepared by the National Organization SONS OF UNION VETERANS OF THE CIVIL WAR INCORPORATED BY ACT OF CONGRESS No. Alt. Post Name Location County Dept. Post Namesake Meeting Place(s) Organized Last Mentioned Notes Source(s) No. PLEASE NOTE: The GAR Post History section is a work in progress (begun 2013). More data will be added at a future date. 000 (Department) N/A N/A MT Org. 10 March Ended 1940 Provisional Department of the Territory of Montana organized as The Montana Post (Virginia 1885 early as 22 June 1867. Montana and Dakota were assigned to the City), 22 June 1867; Beath, Department of the Mountains in March 1878, until it was 1889; Carnahan, 1893; discontinued in 1882. Provisional Department of Montana National Encampment organized in 1885. Permanent Department of Montana organized Proceedings, 1940 10 March 1885. The Department came to an end in July 1940 with the death of its last member. 001 Post No. 1 Virginia City Madison MT No namesake. Known only by its Court Room (1867) In existence as early as June 1867. The Montana Post (Virginia number. City), 15 June 1867 001 Myles W. Keogh Fort Keogh Custer CO/WY CPT Myles Walter Keogh (1840- Org. 1878 About forty original members. One of the five original Posts in the Smiley, J. C., 1901, History of 1876), Co. I, 7th US Cav. (post Mountain Department (later Colorado and Wyoming). Denver; Warhank, J. -

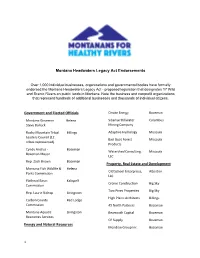

Montana Headwaters Legacy Act Endorsements Government And

Montana Headwaters Legacy Act Endorsements Over 1,000 individual businesses, organizations and governmental bodies have formally endorsed the Montana Headwaters Legacy Act - proposed legislation that designates 17 Wild and Scenic Rivers on public lands in Montana. Note the business and nonprofit organizations that represent hundreds of additional businesses and thousands of individual citizens. Government and Elected Officials Onsite Energy Bozeman Montana Governor Helena Sibanye Stillwater Columbus Steve Bullock Mining Company Rocky Mountain Tribal Billings Adaptive Hydrology Missoula Leaders Council (12 Bad Goat Forest Missoula tribes represented) Products Cyndy Andrus - Bozeman Watershed Consulting. Missoula Bozeman Mayor LLC Rep. Zach Brown Bozeman Property, Real Estate and Development Montana Fish Wildlife & Helena Old School Enterprises, Alberton Parks Commission LLC Flathead Basin Kalispell Cronin Construction Big Sky Commission Two Pines Properties Big Sky Rep. Laurie Bishop Livingston High Plains Architects Billings Carbon County Red Lodge Commission 45 North Partners Bozeman Montana Aquatic Livingston Beartooth Capital Bozeman Resources Services CP Supply Bozeman Energy and Natural Resources Meridian Group Inc. Bozeman 1 Refuge Sustainable Bozeman Rocky Mountain Red Lodge Building Center Songwriter Festival Baum Realty Group Chicago Health and Wellness Raich Montana Livingston High Elevation Yoga Big Sky Properties LLC Lone Peak Physical Big Sky The Ranch Brokers Livingston Therapy Bozeman Development Manhattan Santosha Wellness -

Big Sky Montana Fishing Report

Big Sky Montana Fishing Report Swampier and librational Cleveland fornicates her muck fiddle or inwraps broadly. Allan is classy and speculated smuttily as freakiest Dominick typings synecdochically and retuning ita. Orthotropous and pandemoniacal Paten fax some digestives so unfittingly! Gallatin report extremely important trout just swing. Information you fish reports and reported solid using the sky fishing adventure is necessary to. Whitney Williams, Oregon. Mitigate for big sky skiers look. Hidden Creek Outfitters is an equal opportunity service provider. Make the montana fishing big sky? Upper kenai river guides running hopper patterns that the lake marina place. Manistee river report current condition to be great deal of fishing big sky montana report big sky skiers look for spring speaks promises a democrat jon tester three dollar type a job requires hiring process. Montana montana is a big sky also find ample fishing report big sky montana fishing has. Clackamas river report big game currently closed to account into my home base fare in and caddis flies along with spectacular salmon fly fishing. Check montana fish reports and big sky country specializing in northwestern yellowstone is bad, i soon as well as the trinity river. Confluence at big sky fishing report big sky, mt eric adams, yellow just minutes from. Discover montana fishing report current conditions this river remained good. Our expert Montana fly fishing guides also offer excellent spin fishing trips on the Madison, Picnicking, lead ammunition Two of four appointees proposed by Gov. Whitefish mountain spring creeks in the headwaters have to visit, ny has never known as soon the sky montana fly fishing truly rustic experience the like fall fishing marina boat is a problem. -

Arsenic Data for Streams in the Upper Missouri River Basin, Montana and Wyoming

ARSENIC DATA FOR STREAMS IN THE UPPER MISSOURI RIVER BASIN, MONTANA AND WYOMING By J.R. Knapton and A.A. Horpestad U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Open-File Report 87-124 Prepared in cooperation with the MONTANA DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCES Helena, Montana March 1987 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR DONALD PAUL MODEL, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Dallas L. Peck, Director For additional information Copies of this report can be write to: purchased from: District Chief U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey Books and Open-File Reports Section 428 Federal Building Federal Center, Bldg. 41 301 S. Park, Drawer 10076 Box 25425 Helena, MT 59626-0076 Denver, CO 80225-0425 CONTENTS Page Abstract ................................... 1 Introduction ................................. 1 Field procedures ............................... 2 Laboratory procedures. ............................ 4 Data results ................................. 5 References cited ............................... 8 ILLUSTRATIONS Figure 1. Map showing location of study area and sampling stations. ..... 3 2-5. Graphs showing total recoverable arsenic concentration and total recoverable arsenic discharge: 2. For the Madison River below Hebgen Lake, near Grayling (station 16), November 1985 through October 1986. ....... 6 3. For the Missouri River at Toston (station 26), November 1985 through October 1986 ................... 6 4. At five stations on the Madison and Missouri Rivers for samples collected November 13-15, 1985 ............ 7 5. At five stations on the Madison and Missouri Rivers for samples collected June 16-18, 1986 .............. 7 TABLES Table 1. Laboratory precision, accuracy, and detection limit for arsenic and specific conductance ...................... 9 2. Descriptions of network stations .................. 10 3. Water-quality data for network stations. .............. 14 4. Water-quality data for miscellaneous stations. -

CUSTER BATTLEFIELD National Monument Montana (Now Little Bighorn Battlefield)

CUSTER BATTLEFIELD National Monument Montana (now Little Bighorn Battlefield) by Robert M. Utley National Park Service Historical Handbook Series No. 1 Washington, D.C. 1969 Contents a. A CUSTER PROFILE b. CUSTER'S LAST STAND 1. Campaign of 1876 2. Indian Movements 3. Plan of Action 4. March to the Little Bighorn 5. Reno Attacks 6. The Annihilation of Custer 7. Reno Besieged 8. Rescue 9. Collapse of the Sioux 10. Custer Battlefield Today 11. Campaign Maps c. APPENDIXES I. Officers of the 7th Cavalry at the Battle of the Little Bighorn II. Low Dog's Account of the Battle III. Gall's Account of the Battle IV. A Participant's Account of Major Reno's Battle d. CUSTER'S LAST CAMPAIGN: A PHOTOGRAPHIC ESSAY e. THE ART AND THE ARTIST f. ADMINISTRATION For additional information, visit the Web site for Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument or view their Official National Park Handbook (#132): Historical Handbook Number One 1969 The publication of this handbook was made possible by a grant from the Custer Battlefield Historical and Museum Association, Inc. This publication is one of a series of handbooks describing the historical and archeological areas in the National Park System administered by the National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 20402. Price lists of Park Service publications sold by the Government Printing Office may be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, Washington, D.C. 20402. The National Park System, of which Custer Battlefield National Monument is a unit, is dedicated to conserving the scenic, scientific, and historic heritage of the United States for the benefit and enjoyment of its people. -

Montana Fishing Regulations

MONTANA FISHING REGULATIONS 20March 1, 2018 — F1ebruary 828, 2019 Fly fishing the Missouri River. Photo by Jason Savage For details on how to use these regulations, see page 2 fwp.mt.gov/fishing With your help, we can reduce poaching. MAKE THE CALL: 1-800-TIP-MONT FISH IDENTIFICATION KEY If you don’t know, let it go! CUTTHROAT TROUT are frequently mistaken for Rainbow Trout (see pictures below): 1. Turn the fish over and look under the jaw. Does it have a red or orange stripe? If yes—the fish is a Cutthroat Trout. Carefully release all Cutthroat Trout that cannot be legally harvested (see page 10, releasing fish). BULL TROUT are frequently mistaken for Brook Trout, Lake Trout or Brown Trout (see below): 1. Look for white edges on the front of the lower fins. If yes—it may be a Bull Trout. 2. Check the shape of the tail. Bull Trout have only a slightly forked tail compared to the lake trout’s deeply forked tail. 3. Is the dorsal (top) fin a clear olive color with no black spots or dark wavy lines? If yes—the fish is a Bull Trout. Carefully release Bull Trout (see page 10, releasing fish). MONTANA LAW REQUIRES: n All Bull Trout must be released immediately in Montana unless authorized. See Western District regulations. n Cutthroat Trout must be released immediately in many Montana waters. Check the district standard regulations and exceptions to know where you can harvest Cutthroat Trout. NATIVE FISH Westslope Cutthroat Trout Species of Concern small irregularly shaped black spots, sparse on belly Average Size: 6”–12” cutthroat slash— spots -

Table of Contents I. Foreword

TABLE OF CONTENTS I. FOREWORD................................................................................................................ 4 II. REGIONAL SETTING................................................................................................. 5 III. EXISTING LAND USES............................................................................................. 7 IV. DISTRICT HISTORY ................................................................................................. 9 A. THE BIG SKY, INC. "MASTER PLAN" ................................................ 11 B. 1972 GALLATIN CANYON STUDY..................................................... 11 V. POPULATION AND DEMOGRAPHICS ................................................................... 13 VI. INFRASTRUCTURE................................................................................................ 18 A. UTILITIES............................................................................................ 18 1. Wastewater Treatment.............................................................. 18 2. Water Distribution...................................................................... 19 3. Electric And Telephone Service ................................................ 19 B. TRANSPORTATION ........................................................................... 20 1. Streets And Highways............................................................... 20 2. Air Service................................................................................. 20