OVERCOMING OBSCURITY the Yellowstone Architecture of Robert C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Park Service Mission 66 Era Resources B

NPS Form 10-900-b (Rev. 01/2009) 0MB No. 1024-0018 (Expires 5/31/2012) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form Is used for documenting property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructil'.r!§ ~ ~ tloDpl lj~~r Bulletin How to Complete the Mulliple Property Doc11mentatlon Form (formerly 16B). Complete each item by entering the req lBtEa\oJcttti~ll/~ a@i~8CPace, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items X New Submission Amended Submission AUG 1 4 2015 ---- ----- Nat Register of Historie Places A. Name of Multiple Property Listing NatioAal Park Service National Park Service Mission 66 Era Resources B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) Pre-Mission 66 era, 1945-1955; Mission 66 program, 1956-1966; Parkscape USA program, 1967-1972, National Park Service, nation-wide C. Form Prepared by name/title Ethan Carr (Historical Landscape Architect); Elaine Jackson-Retondo, Ph.D., (Historian, Architectural); Len Warner (Historian). The Collaborative Inc.'s 2012-2013 team comprised Rodd L. Wheaton (Architectural Historian and Supportive Research), Editor and Contributing Author; John D. Feinberg, Editor and Contributing Author; and Carly M. Piccarello, Editor. organization the Collaborative, inc. date March 2015 street & number ---------------------2080 Pearl Street telephone 303-442-3601 city or town _B_o_ul_d_er___________ __________st_a_te __ C_O _____ zi~p_c_o_d_e_8_0_30_2 __ _ e-mail [email protected] organization National Park Service Intermountain Regional Office date August 2015 street & number 1100 Old Santa Fe Trail telephone 505-988-6847 city or town Santa Fe state NM zip code 87505 e-mail sam [email protected] D. -

Grand Canyon; No Trees As Large Or As the Government Builds Roads and Trails, Hotels, Cabins GASOLINE Old As the Sequoias

GET ASSOCIATED WITH SMILING ASSOCIATED WESTERN DEALERS NATIONAL THE FRIENDLY SERVICE r OF THE WEST PARKS OUR NATIONAL PARKS "STATURE WAS GENEROUS first, and then our National sunny wilderness, for people boxed indoors all year—moun Government, in giving us the most varied and beautiful tain-climbing, horseback riding, swimming, boating, golf, playgrounds in all the world, here in Western America. tennis; and in the winter, skiing, skating and tobogganing, You could travel over every other continent and not see for those whose muscles cry for action—Nature's loveliness as many wonders as lie west of the Great Divide in our for city eyes—and for all who have a lively curiosity about own country . not as many large geysers as you will find our earth: flowers and trees, birds and wild creatures, here in Yellowstone; no valley (other nations concede it) as not shy—and canyons, geysers, glaciers, cliffs, to show us FLYING A strikingly beautiful as Yosemite; no canyon as large and how it all has come to be. vividly colored as our Grand Canyon; no trees as large or as The Government builds roads and trails, hotels, cabins GASOLINE old as the Sequoias. And there are marvels not dupli and camping grounds, but otherwise leaves the Parks un touched and unspoiled. You may enjoy yourself as you wish. • cated on any scale, anywhere. Crater Lake, lying in the cav The only regulations are those necessary to preserve the ity where 11 square miles of mountain fell into its own ASSOCIATED Parks for others, as you find them—and to protect you from MAP heart; Mt. -

The George Wright Forum

The George Wright Forum The GWS Journal of Parks, Protected Areas & Cultural Sites volume 27 number 1 • 2010 Origins Founded in 1980, the George Wright Society is organized for the pur poses of promoting the application of knowledge, fostering communica tion, improving resource management, and providing information to improve public understanding and appreciation of the basic purposes of natural and cultural parks and equivalent reserves. The Society is dedicat ed to the protection, preservation, and management of cultural and natural parks and reserves through research and education. Mission The George Wright Society advances the scientific and heritage values of parks and protected areas. The Society promotes professional research and resource stewardship across natural and cultural disciplines, provides avenues of communication, and encourages public policies that embrace these values. Our Goal The Society strives to he the premier organization connecting people, places, knowledge, and ideas to foster excellence in natural and cultural resource management, research, protection, and interpretation in parks and equivalent reserves. Board of Directors ROLF DIA.MANT, President • Woodstock, Vermont STEPHANIE T(K)"1'1IMAN, Vice President • Seattle, Washington DAVID GKXW.R, Secretary * Three Rivers, California JOHN WAITHAKA, Treasurer * Ottawa, Ontario BRAD BARR • Woods Hole, Massachusetts MELIA LANE-KAMAHELE • Honolulu, Hawaii SUZANNE LEWIS • Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming BRENT A. MITCHELL • Ipswich, Massachusetts FRANK J. PRIZNAR • Gaithershnrg, Maryland JAN W. VAN WAGTENDONK • El Portal, California ROBERT A. WINFREE • Anchorage, Alaska Graduate Student Representative to the Board REBECCA E. STANFIELD MCCOWN • Burlington, Vermont Executive Office DAVID HARMON,Executive Director EMILY DEKKER-FIALA, Conference Coordinator P. O. Box 65 • Hancock, Michigan 49930-0065 USA 1-906-487-9722 • infoldgeorgewright.org • www.georgewright.org Tfie George Wright Forum REBECCA CONARD & DAVID HARMON, Editors © 2010 The George Wright Society, Inc. -

Architecture of Yellowstone a Microcosm of American Design by Rodd L

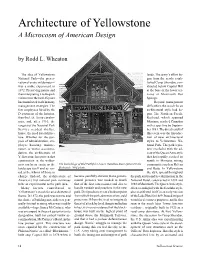

Architecture of Yellowstone A Microcosm of American Design by Rodd L. Wheaton The idea of Yellowstone lands. The army’s effort be- National Park—the preser- gan from the newly estab- vation of exotic wilderness— lished Camp Sheridan, con- was a noble experiment in structed below Capitol Hill 1872. Preserving nature and at the base of the lower ter- then interpreting it to the park races at Mammoth Hot visitors over the last 125 years Springs. has manifested itself in many Beyond management management strategies. The difficulties, the search for an few employees hired by the architectural style had be- Department of the Interior, gun. The Northern Pacific then the U.S. Army cavalry- Railroad, which spanned men, and, after 1916, the Montana, reached Cinnabar rangers of the National Park with a spur line by Septem- Service needed shelter; ber 1883. The direct result of hence, the need for architec- this event was the introduc- ture. Whether for the pur- tion of new architectural pose of administration, em- styles to Yellowstone Na- ployee housing, mainte- tional Park. The park’s pio- nance, or visitor accommo- neer era faded with the ad- dation, the architecture of vent of the Queen Anne style Yellowstone has proven that that had rapidly reached its construction in the wilder- zenith in Montana mining ness can be as exotic as the The burled logs of Old Faithful’s Lower Hamilton Store epitomize the communities such as Helena landscape itself and as var- Stick style. NPS photo. and Butte. In Yellowstone ied as the whims of those in the style spread throughout charge. -

Lake Guernsey State Park National Historic Landmark Form Size

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 LAKE GUERNSEY STATE PARK Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service_____________________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: LAKE GUERNSEY STATE PARK Other Name/Site Number: Lake Guernsey Park, Guernsey Lake Park, Guernsey State Park 2. LOCATION Street & Number: One Mile NW of Guernsey, WY Not for publication: City/Town: Guernsey Vicinity: X State: Wyoming County: Platte Code: 031 Zip Code: 82002 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: __ Building(s): __ Public-Local: __ District: X Public-State: __ Site: __ Public-Federal: X Structure: __ Object: __ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 14 37 buildings 0 sites 43 9 structures 0 0 objects 60 46 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: Park historic district listed in 1980. resources not enumerated Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: Historic Park Landscapes in National and State Parks, 1995 NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 LAKE GUERNSEY STATE PARK Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service_____________________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination _ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

Yellowstone National Park! Renowned Snowcapped Eagle Peak

YELLOWSTONE THE FIRST NATIONAL PARK THE HISTORY BEHIND YELLOWSTONE Long before herds of tourists and automobiles crisscrossed Yellowstone’s rare landscape, the unique features comprising the region lured in the West’s early inhabitants, explorers, pioneers, and entrepreneurs. Their stories helped fashion Yellowstone into what it is today and initiated the birth of America’s National Park System. Native Americans As early as 10,000 years ago, ancient inhabitants dwelled in northwest Wyoming. These small bands of nomadic hunters wandered the country- side, hunting the massive herds of bison and gath- ering seeds and berries. During their seasonal travels, these predecessors of today’s Native American tribes stumbled upon Yellowstone and its abundant wildlife. Archaeologists have discov- ered domestic utensils, stone tools, and arrow- heads indicating that these ancient peoples were the first humans to discover Yellowstone and its many wonders. As the region’s climate warmed and horses Great Fountain Geyser. NPS Photo by William S. Keller were introduced to American Indian tribes in the 1600s, Native American visits to Yellowstone became more frequent. The Absaroka (Crow) and AMERICA’S FIRST NATIONAL PARK range from as low as 5,314 feet near the north Blackfeet tribes settled in the territory surrounding entrance’s sagebrush flats to 11,358 feet at the Yellowstone and occasionally dispatched hunting Welcome to Yellowstone National Park! Renowned snowcapped Eagle Peak. Perhaps most interesting- parties into Yellowstone’s vast terrain. Possessing throughout the world for its natural wonders, ly, the park rests on a magma layer buried just one no horses and maintaining an isolated nature, the inspiring scenery, and mysterious wild nature, to three miles below the surface while the rest of Shoshone-Bannock Indians are the only Native America’s first national park is nothing less than the Earth lies more than six miles above the first American tribe to have inhabited Yellowstone extraordinary. -

2016 Experience Planner a Guide to Lodging, Camping, Dining, Shopping, Tours and Activities in Yellowstone Don’T Just See Yellowstone

2016 Experience Planner A Guide to Lodging, Camping, Dining, Shopping, Tours and Activities in Yellowstone Don’t just see Yellowstone. Experience it. MAP LEGEND Contents DINING Map 2 OF Old Faithful Inn Dining Room Just For Kids 3 Ranger-Led Programs 3 OF Bear Paw Deli Private Custom Tours 4 OF Obsidian Dining Room Rainy Day Ideas 4 OF Geyser Grill On Your Own 5 Wheelchair Accessible Vehicles 6 OF Old Faithful Lodge Cafeteria Road Construction 6 GV Grant Village Dining Room GV Grant Village Lake House CL Canyon Lodge Dining Room Locations CL Canyon Lodge Cafeteria CL Canyon Lodge Deli Mammoth Area 7-9 LK Lake Yellowstone Hotel Dining Room Old Faithful Area 10-14 Lake Yellowstone Area 15-18 LK Lake Yellowstone Hotel Deli Canyon Area 19-20 LK Lake Lodge Cafeteria Roosevelt Area 21-22 M Mammoth Hot Springs Dining Room Grant Village Area 23-25 Our Softer Footprint 26 M Mammoth Terrace Grill Campground Info 27-28 RL Roosevelt Lodge Dining Room Animals In The Park 29-30 RL Old West Cookout Thermal Features 31-32 Winter 33 Working in Yellowstone 34 SHOPPING For Camping and Summer Lodging reservations, a $15 non-refundable fee will OF be charged for any changes or cancellations Bear Den Gift Shop that occur 30 days prior to arrival. For OF Old Faithful Inn Gift Shop cancellations made within 2 days of arrival, OF The Shop at Old Faithful Lodge the cancellation fee will remain at an amount GV Grant Village Gift Shop equal to the deposit amount. CL Canyon Lodge Gift Shop (Dates and rates in this Experience Planner LK Lake Hotel Gift Shop are subject to change without notice. -

YELLOWSTONE National Park WYOMING - MONTANA- IDAHO

YELLOWSTONE National Park WYOMING - MONTANA- IDAHO UNITED STATES RAILROAD ADMINISTRATION N AT IONAU PARK SERIES Copyright by Hayncs, St. Paul Riverside Geyser—Unlike most Geysers it spouts obliquely instead of vertically. Its arching column of water is thrown into the Fireholc River Page two An Appreciation of Yellowstone National Park By EMERSON HOUGH Author oj "<CTic Mississippi Bubble" "54-40 or Fight" "'Che Way to the West," etc. Written Especially for the United States Railroad Administration FTER every war there comes a day of diligence. Usually war is followed by a rush of soldiers back to the soil. We have 3,000,000 soldiers, a large per cent of whom are seeking farms. This means the early use of every reclaimable acre of American soil. 11 means that the wildernesses of America soon will be no more. Our great National Parks are sections of the old American wilder ness preserved practically unchanged. They are as valuable, acre for acre, as the richest farm lands. They feed the spirit, the soul, the character of America. Who can measure the value, even to-day, of a great national reserve such as the Yellowstone Park? In twenty years it will be beyond all price, for in twenty years we shall have no wild America. The old days are gone forever. Their memories are ours personally. We ought personally to understand, to know, to prize and cherish them. Of all the National Parks Yellowstone is the wildest and most universal in its appeal. There is more to see there—more different sorts of things, more natural wonders, more strange and curious things, more scope, more variety—a longer list of astonishing sights—than any half dozen of the other parks combined could offer. -

Yellowstone/Teton

YELLOWSTONE/TETON Wyoming | 6 days - 5 nights | from $2,898 / person Trip Summary: This six-day adventure shows off not only one, but two of our national treasures: Grand Teton and Yellowstone National Parks. In close proximity but featuring completely different geology, you’ll hike past steaming, spraying geysers in Yellowstone and pedal past tall, snow-capped peaks in the Tetons. Cycle through a 1988 wildfire burn as you make your way around the third largest hot spring in the world. Paddle calm waters in your canoe or kayak underneath towering Mount Moran on Jackson Lake. Take on one rapid after another while rafting a scenic section of the Snake River. By night, raise a glass in a toast to a day well spent exploring several of our nation’s most beautiful parks. www.austinadventures.com | 800-575-1540 1 THE DAY TO DAY Day 1: Antelope Flats / Old Faithful Pick up in Jackson and head immediately into Grand Teton National Park for a welcome meeting • Our first bike ride on Antelope Flats promises stunning views and hopefully some wildlife if we keep our eyes peeled • Shuttle north to the south entrance of Yellowstone National Park • Take a hike through the Upper Geyser Basin towards your first evening’s hotel, taking in the sights, sounds and smells along the way • Be sure to catch an eruption of the famous Old Faithful geyser before dinner! • Overnight Old Faithful Inn or Old Faithful Snow Lodge (L, D) Day 2: Lower Geyser Basin / Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone To start the day, first stop off at the Lower Geyser Basin’s Fountain Paints -

“For the Benefit and Enjoyment of the People”

“For the Benefit and Enjoyment of the People” A HISTORY OF CONCESSION DEVELOPMENT IN YELLOWSTONE NATIONAL PARK, 1872–1966 By Mary Shivers Culpin National Park Service, Yellowstone Center for Resources Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming YCR-CR-2003-01, 2003 Photos courtesy of Yellowstone National Park unless otherwise noted. Cover photos are Haynes postcards courtesy of the author. Suggested citation: Culpin, Mary Shivers. 2003. “For the Benefit and Enjoyment of the People”: A History of the Concession Development in Yellowstone National Park, 1872–1966. National Park Service, Yellowstone Center for Resources, Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming, YCR-CR-2003-01. Contents List of Illustrations ...................................................................................................................iv Preface .................................................................................................................................... vii 1. The Early Years, 1872–1881 .............................................................................................. 1 2. Suspicion, Chaos, and the End of Civilian Rule, 1883–1885 ............................................ 9 3. Gibson and the Yellowstone Park Association, 1886–1891 .............................................33 4. Camping Gains a Foothold, 1892–1899........................................................................... 39 5. Competition Among Concessioners, 1900–1914 ............................................................. 47 6. Changes Sweep the Park, 1915–1918 -

Seattle Times Building Complex—Printing Plant 1930-31; Addition, 1947

Seattle Times Building Complex—Printing Plant 1930-31; Addition, 1947 1120 John Street 1986200525 see attached page D.T. Denny’s 5th Add. 110 7-12 Onni Group Vacant 300 - 550 Robson Street, Vancouver, BC V6B 2B7 The Blethen Corporation (C. B. Blethen) (The Seattle Times) Printing plant and offices Robert C. Reamer (Metropolitan Building Corporation) , William F. Fey, (Metro- politan Building Corporation) Teufel & Carlson Seattle Times Building Complex—Printing Plant Landmark Nomination, October 2014 LEGAL DESCRIPTION: LOTS 7 THROUGH 12 IN BLOCK 110, D.T. DENNY’S FIFTH ADDITION TO NORTH SEAT- TLE, AS PER PLAT RECORDED IN VOLUME 1 OF PLATS, PAGE 202, RECORDS OF KING COUNTY; AND TOGETHER WITH THOSE PORTIONS OF THE DONATION CLAIM OF D.T. DENNY AND LOUIS DENNY, HIS WIFE, AND GOVERNMENT LOT 7 IN THE SOUTH- EAST CORNER OF SECTION 30, TOWNSHIP 25, RANGE 4 EAST, W. M., LYING WEST- ERLY OF FAIRVIEW AVENUE NORTH, AS CONDEMNED IN KING COUNTY SUPERIOR COURT CAUSE NO. 204496, AS PROVIDE BY ORDINANCE NO. 51975, AND DESCRIBED AS THAT PORTION LYING SOUTHERLY OF THOMAS STREET AS CONVEYED BY DEED RECORDED UNDER RECORDING NO. 2103211, NORTHERLY OF JOHN STREET, AND EASTERLY OF THE ALLEY IN SAID BLOCK 110; AND TOGETHER WITH THE VACATED ALLEY IN BLOCK 110 OF SAID PLAT OF D.T. DENNY’S FIFTH ADDITION, VACATED UNDER SEATTLE ORDINANCE NO. 89750; SITUATED IN CITY OF SEATTLE, COUNTY OF KING, STATE OF WASHINGTON. Evan Lewis, ONNI GROUP 300 - 550 Robson Street, Vancouver, BC V6B 2B7 T: (604) 602-7711, [email protected] Seattle Times Building Complex-Printing Plant Landmark Nomination Report 1120 John Street, Seattle, WA October 2014 Prepared by: The Johnson Partnership 1212 NE 65th Street Seattle, WA 98115-6724 206-523-1618, www.tjp.us Seattle Times Building Complex—Printing Plant Landmark Nomination Report October 2014, page i TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. -

HPC-Schedule-Print-Small.Pdf

Tuesday, September 30th, 2014 Travel to Old Faithful in Yellowstone National Park 4:00 pm Hotel Check-In 5:00 pm Registration & Welcome Reception Old Faithful Lodge Recreation Hall Join old and new friends for a hearty round of hors d’ouevres and a warm welcome from conference partners. Wednesday, October 1st, 2014 7:30 am Registration/coffee at Old Faithful Lodge Recreation Hall 8:00 am Conference Orientation, Goals & Logistics Tom McGrath FAPT, Facilitator Chere Jiusto, Montana Preservation Alliance, Conference Coordinator 8:30 am National Park Service Rustic Architecture Laura Gates, NPS Superintendent Cane River Creole NHP, LA. Ms. Gates will present an overview of park rustic architecture including early hospitality structures and architect Robert Reamer’s structures, such as the Old Faithful Inn at Yellowstone. The landscapes of our national parks contain iconic natural features that are indelibly imprinted in our minds: Old Faithful at Yellowstone; El Capitan and Half Dome at Yosemite; the General Sherman Tree at Sequoia National Park. These natural features frame our perception of the west and our treasured national parks. Synonymous with those iconic landscapes are the masterful buildings that grew out of those special places. Developed by the railroads, concessionaires, private interests, and the National Park Service, a type of architecture evolved during the late 19th and early 20th centuries that possessed strong harmony with the surrounding landscape and connections to cultural traditions. This architecture, most often categorized as “Rustic” served to enhance the visitor experience in these wild places. The architecture, too, frequently became as significant a part of the visitor experience as the national park itself.