Seattle Times Building Complex—Printing Plant 1930-31; Addition, 1947

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Backgrounder: the Seattle Times, Seattle, Washington

Backgrounder The Seattle Times: Interviewed April 22, 2011 Newspaper The Seattle Times Owner The Seattle Times Company (independently owned by the Blethen family) Address 1120 John St., Seattle, WA 98109 Phone number (206) 464-2111 URL Seattletimes.com Circulation Weekdays 253,732; Sundays 346,991 Publisher and CEO Name Frank Blethen Starting Date Started in 1968; became publisher 1985 Phone number 206-464-8502 E-mail [email protected] Newspaper Staff Total FTEs Publication cycle 7 days, a.m. Current Circulation (most recent audited) Weekdays 253,732 Sundays 346,991 E-edition 29,721 Price Weekday newsstand $.75 ($1.00 outside King, Pierce, Snohomish, Kitsap counties) Sunday newsstand $2.00 Subscription annual $291.20 7-days; $163.80 Sundays only E-edition $103.48 Newsprint for Seattle Times only Tons/annual 20,000 Sources of Revenue for Seattle Times only Percentages Circulation 34% Display ads 26% Inserts 19% Special Sections .3% Classified 12% Legal Notices 1% On-line Ads & Fees 8% Trends/Changes over 3 years -28% Digital Pay wall? No Considering a pay wall? Paid digital content yes, but not a true paywall Advertising Is your advertising staff able to provide competitive yes digital services to merchants? Do you use "real time" ads? no Does your advertising department sell "digital Yes, on a limited scale services" such as helping merchants with website Valid Sources, “Who Needs Newspapers?” project; 1916 Pike Pl., Ste 12 #60, Seattle, WA.98101 541-941-8116 www.whoneedsnewspapers.org Backgrounder The Seattle Times: Interviewed April 22, 2011 production? Does your ad department sell electronic coupons or We are involved in a mobile coupon test with AP other modern digital products? Other? Do you generate revenue in partnership with outside Yes, not Yahoo, but numerous local and national digital vendors such as Yahoo? If so, who are they? partners. -

DOCUMENT RESUME INSTITUTION Borough of Manhattan Community

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 423 559 CS 509 903 TITLE New Media. INSTITUTION Borough of Manhattan Community Coll., New York, NY. Inst. for Business Trends Analysis. PUB DATE 1998-00-00 NOTE 65p. PUB TYPE Collected Works Serials (022) JOURNAL CIT Downtown Business Quarterly; vl n3 Sum 1998 EDRS PRICE MF01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Community Colleges; Curriculum Development; *Employment Patterns; Employment Statistics; Mass Media; *Technological Advancement; Technology Education; Two Year Colleges; *World Wide Web IDENTIFIERS City University of New York Manhattan Comm Coll; *New Media; *New York (New York) ABSTRACT This theme issue explores lower Manhattan's burgeoning "New Media" industry, a growing source of jobs in lower Manhattan. The first article, "New Media Manpower Issues" (Rodney Alexander), addresses manpower, training, and workforce demands faced by new media companies in New York City. The second article, "Case Study: Hiring Dynamid" (John Montanez), examines the experience of new employees at a new media company that creates corporate websites. The third article, "New Media @ BMCC" (Alice Cohen, Alberto Errera, and MeteKok), describes the Borough of Manhattan Community College's developing new media curriculum, and includes an interview with John Gilbert, Executive Vice President and Chief Operating Officer of Rudin Management, the company that transformed 55 Broad Street into the New York Information Technology Center. The fourth section "Downtown Data" (Xenia Von Lilien-Waldau) presents data in seven categories: employment, services and utilities, construction, transportation, real estate, and hotels and tourism. The fifth article, "Streetscape" (Anne Eliet) examines Newspaper Row, where Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph HearsL ran their empires. (RS) ******************************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

How Newsletters Are Redefining Media Subscriptions Dawn Mcmullan June 2018 How Newsletters Are Redefining Media Subscriptions Dawn Mcmullan

June 2018 How Newsletters Are Redefining Media Subscriptions Dawn McMullan June 2018 How Newsletters Are Redefining Media Subscriptions Dawn McMullan Author About the author 3 Dawn McMullan Executive summary 4 Introduction 8 Contributors Rob Josephs Chapter 1: The perfect storm that made e-mail a killer Earl J. Wilkinson audience strategy 11 A. Why e-mail works: personalisation, control, loyalty 12 Editor B. Two types of newsletters 14 Carly Price Chapter 2: E-mail engagement 101 17 Design & Layout A. Establish your goals 18 Danna Emde B. Get to know your audience 19 C. Determine newsletter frequency 20 D. Develop the content 20 E. Write awesome subject lines 21 F. Stay on top of tech and metrics 22 Chapter 3: Trends and objectives at media companies 23 A. How to encourage frequency 23 B. Early benchmarks 24 C. Global and national players 24 D. Digital pure-plays 28 E. Metropolitan dailies 29 F. Pop-up newsletters 30 G. Conclusions 31 Chapter 4: Newsletter case studies 33 A. The Boston Globe 33 B. Financial Times 38 C. El País 43 D. Cox Media Group 46 Chapter 5: Conclusion 51 INMA | HOW NEWSLETTERS ARE REDEFINING MEDIA SUBSCRIPTIONS 2 About the author Dawn McMullan is senior editor at INMA, based in Dallas, Texas, USA. She has been in the news media industry for for 30+ years working as an editor/writer. Her favorite newsletter (aside from the INMA newsletter she creates five days a week, of course) is The Lily. About the International News Media Association (INMA) The International News Media Association (INMA) is a global community of market-leading news media companies reinventing how they engage audiences and grow revenue in a multi-media environment. -

No. 13-3148 in the UNITED STATES COURT of APPEALS for THE

Case: 13-3148 Document: 20-2 Filed: 01/10/2014 Pages: 43 No. 13-3148 IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SEVENTH CIRCUIT INTERCON SOLUTIONS, INC., Plaintiff-Appellee, v. BASEL ACTION NETWORK AND JAMES PUCKETT, Defendants-Appellants. ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ILLINOIS Case No. 12-CV-6814 (Hon. Virginia M. Kendall) _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE ADVANCE PUBLICATIONS, INC., ALLIED DAILY NEWSPAPERS OF WASHINGTON, AMERICAN SOCIETY OF NEWS EDITORS, ASSOCIATION OF ALTERNATIVE NEWSMEDIA, THE ASSOCIATION OF AMERICAN PUBLISHERS, INC., BLOOMBERG L.P., CABLE NEWS NETWORK, INC., DOW JONES & COMPANY, INC., THE E.W. SCRIPPS COMPANY, HEARST CORPORATION, THE MCCLATCHY COMPANY, MEDIA LAW RESOURCE CENTER, THE NATIONAL PRESS CLUB, NATIONAL PRESS PHOTOGRAPHERS ASSOCIATION, NATIONAL PUBLIC RADIO, INC., NEWS CORPORATION, NEWSPAPER ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA, ONLINE NEWS ASSOCIATION, PRO PUBLICA, INC., RADIO TELEVISION DIGITAL NEWS ASSOCIATION, REPORTERS COMMITTEE FOR FREEDOM OF THE PRESS, SEATTLE TIMES COMPANY, SOCIETY OF PROFESSIONAL JOURNALISTS, TIME INC., TRIBUNE COMPANY, THE WASHINGTON NEWSPAPER PUBLISHERS ASSOCIATION, AND THE WASHINGTON POST IN SUPPORT OF DEFENDANTS-APPELLANTS AND REVERSAL _____________________________________________________________________________________________ Bruce E. H. Johnson Laura R. Handman Ambika K. Doran Alison Schary DAVIS WRIGHT TREMAINE LLP DAVIS WRIGHT TREMAINE LLP 1201 Third Avenue, Suite 2200 1919 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Seattle, WA 98101 Suite 800 (206) 622-3150 Washington, DC 20006 (202) 973-4200 Thomas R. Burke DAVIS WRIGHT TREMAINE LLP Counsel for Amici Curiae 505 Montgomery Street, Suite 800 San Francisco, CA 94111 (*Of counsel listed on inside cover) (415) 276-6500 Case: 13-3148 Document: 20-2 Filed: 01/10/2014 Pages: 43 OF COUNSEL Richard A. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NFS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (Rdv: 8-W5) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations of eligibility for individual properties or districts. See Instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, styles, materials, and areas of significance, enter only the categories and subcategories listed in the Instructions. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Type all entries. 1. Name of Property historic name Mickelson, Die, CJabm other names/site number IN/A 2. Location street & number Lot 4o, soutn snore Lalce Uumauit EH not for publication city, town Qumault 0 vicinity state Washington code WA county TJrays Harbor code U2T zlpcodefy57r 3. Classification Ownership of Property Category of Property Number of Resources within Property B3 private ES building(s) Contributing Noncontributing CU public-local D district 2 _ buildings D public-State D site _ _ sites B3 public-Federal O structure _ _ structures CH object objects 2~ U~ Total Name of related multiple property listing: Number of contributing resources previously N/A listed in the National Register N/A 4. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this C3 nomination d request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

Isabel Amiano

isabel amiano www.isabelamiano.com.ar ARCHITECTURE NEW YORK New York in fact has three separately recognizable skylines: Midtown Manhattan, Downtown Manhattan (also known as Lower Manhattan), and Downtown Brooklyn. The largest of these skylines is in Midtown, which is the largest central business district in the world, and also home to such notable buildings as the Empire State Building, the Chrysler Building, and Rockefeller Center. The Downtown skyline comprises the third largest central business district in the United States (after Midtown and Chicago's Loop), and was once characterized by the presence of the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center. Today it is undergoing the rapid reconstruction of Lower Manhattan, and will include the new One World Trade Center Freedom Tower, which will rise to a height of 1776 ft. when completed in 2010. The Downtown skyline will also be getting notable additions soon from such architects as Santiago Calatrava and Frank Gehry. Also, Goldman Sachs is building a 225 meter (750 feet) tall, 43 floor building across the street from the World Trade Center site. New York City has a long history of tall buildings. It has been home to 10 buildings that have held the world's tallest fully inhabitable building title at some point in history, although half have since been demolished. The first building to bring the world's tallest title to New York was the New York World Building, in 1890. Later, New York City was home to the world's tallest building for 75 continuous years, starting with the Park Row Building in 1899 and ending with 1 World Trade Center upon completion of the Sears Tower in 1974. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMBNo. 1024-0018 (Rev. 8-86) "» United States Department of the Interior ' .J National Park Service Lui « P r% o "•> 10Q1 M!" :\ '~J <* »w3 I National Register of Historic Places NATIONAL Registration Form REGISTER This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations of eligibility for individual properties or districts. See Instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, styles, materials, and areas of significance, enter only the categories and subcategories listed in the Instructions. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Type all entries. 1. Name of Property historic name_________1411 Fourth Avenue Building_____________________________ other names/site number N/A „ 2. Location street & number 1411 Fourth Ave. D not for publication city, town Seattle IZ1 vicinity state Washington code WA county King code 033 zip code 98101 3. Classification Ownership of Property Category of Property Number of Resources within Property IS private K] building(s) Contributing Noncontributing [U public-local C] district 1 _ buildings D public-State IH site _ _ sites C~l public-Federal [U structure _ _ structures CH object objects 1 0 Total Name of related multiple property listing: Number of contributing resources previously N/A_________________ listed in the National Register 0 4. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this DO nomination CD request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places ancfVneets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60 . -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional certification comments, entries, and narrative items on continuation sheets if needed (NPS Form 10-900a). 1. Name of Property historic name Bon Marche Department Store other names/site number Bon Marche Building; Macy’s Building 2. Location street & number 300 Pine Street not for publication city or town Seattle vicinity state WASHINGTON code WA county KING code 033 zip code 98122 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property X_ meets _ does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following level(s) of significance: national statewide local Applicable National Register Criteria X A B X C D Signature of certifying official/Title Date WASHINGTON SHPO State or Federal agency/bureau or Tribal Government In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register criteria. -

A Different Kind of Gentrification: Seattle and Its Relationship with Industrial Land

A Different Kind of Gentrification: Seattle and its Relationship with Industrial Land David Tomporowski A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Urban Planning University of Washington 2019 Committee: Edward McCormack Christine Bae Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Department of Urban Design and Planning College of Built Environments ©Copyright 2019 David Tomporowski University of Washington Abstract A Different Kind of Gentrification: Seattle and its Relationship with Industrial Land David Tomporowski Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Edward McCormack Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering / Department of Urban Design and Planning Industry in Seattle often talks about how they are facing their own kind of gentrification. Rising property values, encroaching pressure for different land uses, and choking transportation all loom as reasons for industrial businesses to relocate out of the city. This research explores this phenomenon of industrial gentrification through a case study of Seattle’s most prominent industrial area: the SODO (“South Of Downtown”) neighborhood. My primary research question asks what the perception and reality of the state of industrial land designation and industrial land use gentrification in Seattle is. Secondary research questions involve asking how industrial land designation and industrial land use can be defined in Seattle, what percentage of land is zoned industrial in the SODO neighborhood, and what percentage of the land use is considered industrial in the SODO neighborhood. Finally, subsequent effects on freight transportation and goods movement will be considered. By surveying actual industrial land use compared to i industrially-zoned land, one can conclude whether industry’s complaints are accurate and whether attempts to protect industrial land uses are working. -

Architecture of Yellowstone a Microcosm of American Design by Rodd L

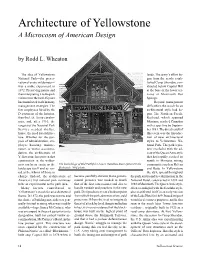

Architecture of Yellowstone A Microcosm of American Design by Rodd L. Wheaton The idea of Yellowstone lands. The army’s effort be- National Park—the preser- gan from the newly estab- vation of exotic wilderness— lished Camp Sheridan, con- was a noble experiment in structed below Capitol Hill 1872. Preserving nature and at the base of the lower ter- then interpreting it to the park races at Mammoth Hot visitors over the last 125 years Springs. has manifested itself in many Beyond management management strategies. The difficulties, the search for an few employees hired by the architectural style had be- Department of the Interior, gun. The Northern Pacific then the U.S. Army cavalry- Railroad, which spanned men, and, after 1916, the Montana, reached Cinnabar rangers of the National Park with a spur line by Septem- Service needed shelter; ber 1883. The direct result of hence, the need for architec- this event was the introduc- ture. Whether for the pur- tion of new architectural pose of administration, em- styles to Yellowstone Na- ployee housing, mainte- tional Park. The park’s pio- nance, or visitor accommo- neer era faded with the ad- dation, the architecture of vent of the Queen Anne style Yellowstone has proven that that had rapidly reached its construction in the wilder- zenith in Montana mining ness can be as exotic as the The burled logs of Old Faithful’s Lower Hamilton Store epitomize the communities such as Helena landscape itself and as var- Stick style. NPS photo. and Butte. In Yellowstone ied as the whims of those in the style spread throughout charge. -

Major Offices, Including T- Mobile’S Headquarters Within the Newport Corporate Center, Due to Its Easy Access Along the I-90 Corridor

Commercial Revalue 2018 Assessment roll OFFICE AREA 280 King County, Department of Assessments Seattle, Washington John Wilson, Assessor Department of Assessments King County Administration Bldg. John Wilson 500 Fourth Avenue, ADM-AS-0708 Seattle, WA 98104-2384 Assessor (206)263-2300 FAX(206)296-0595 Email: [email protected] http://www.kingcounty.gov/assessor/ Dear Property Owners, Our field appraisers work hard throughout the year to visit properties in neighborhoods across King County. As a result, new commercial and residential valuation notices are mailed as values are completed. We value your property at its “true and fair value” reflecting its highest and best use as prescribed by state law (RCW 84.40.030; WAC 458-07-030). We continue to work hard to implement your feedback and ensure we provide accurate and timely information to you. We have made significant improvements to our website and online tools to make interacting with us easier. The following report summarizes the results of the assessments for your area along with a map. Additionally, I have provided a brief tutorial of our property assessment process. It is meant to provide you with background information about the process we use and our basis for the assessments in your area. Fairness, accuracy and transparency set the foundation for effective and accountable government. I am pleased to continue to incorporate your input as we make ongoing improvements to serve you. Our goal is to ensure every single taxpayer is treated fairly and equitably. Our office is here to serve you. Please don’t hesitate to contact us if you ever have any questions, comments or concerns about the property assessment process and how it relates to your property. -

Yellowstone National Park! Renowned Snowcapped Eagle Peak

YELLOWSTONE THE FIRST NATIONAL PARK THE HISTORY BEHIND YELLOWSTONE Long before herds of tourists and automobiles crisscrossed Yellowstone’s rare landscape, the unique features comprising the region lured in the West’s early inhabitants, explorers, pioneers, and entrepreneurs. Their stories helped fashion Yellowstone into what it is today and initiated the birth of America’s National Park System. Native Americans As early as 10,000 years ago, ancient inhabitants dwelled in northwest Wyoming. These small bands of nomadic hunters wandered the country- side, hunting the massive herds of bison and gath- ering seeds and berries. During their seasonal travels, these predecessors of today’s Native American tribes stumbled upon Yellowstone and its abundant wildlife. Archaeologists have discov- ered domestic utensils, stone tools, and arrow- heads indicating that these ancient peoples were the first humans to discover Yellowstone and its many wonders. As the region’s climate warmed and horses Great Fountain Geyser. NPS Photo by William S. Keller were introduced to American Indian tribes in the 1600s, Native American visits to Yellowstone became more frequent. The Absaroka (Crow) and AMERICA’S FIRST NATIONAL PARK range from as low as 5,314 feet near the north Blackfeet tribes settled in the territory surrounding entrance’s sagebrush flats to 11,358 feet at the Yellowstone and occasionally dispatched hunting Welcome to Yellowstone National Park! Renowned snowcapped Eagle Peak. Perhaps most interesting- parties into Yellowstone’s vast terrain. Possessing throughout the world for its natural wonders, ly, the park rests on a magma layer buried just one no horses and maintaining an isolated nature, the inspiring scenery, and mysterious wild nature, to three miles below the surface while the rest of Shoshone-Bannock Indians are the only Native America’s first national park is nothing less than the Earth lies more than six miles above the first American tribe to have inhabited Yellowstone extraordinary.