The Statue of Zeus at Olympia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Bronze Pail of Athena Alalkomenia

A BRONZE PAIL OF ATHENA ALALKOMENIA (PLATES 31-34) T HE remarkable archaic Greek bronze vessel published here (P1. 31, a) was l.4 purchased in Mantinea in Arcadia in the spring of 1957 and donated to the Museum in Tegea where other antiquities from the same region have their abode. It had been found by a local shepherd some distance to the north of the ruins of Man- tinea but, unfortunately, the exact location of the discovery could not be ascertained.' The major part of the vessel is preserved, including about half of its upper profiled edge and one attachment for the handle which passed through its upper ring. The whole of this ring is still filled with iron and it is evident that the missing handle was made of this material. The carefully proportioned body has a height of 0.241 m. to the upper edge of the lip. Its largest diameter, 0.215 m., is slightly smaller than the total height and exactly the same both at the outer edge of the lip and at the greatest width of the body which, in turn, occurs precisely half way between that edge and the bottom of the vessel, 0.12 m. distant from both. The upper face of the lip inclines outward slightly to allow overspilling liquid to run off, as it were, from an architectural cornice. The proportion of diameter to height, the rounded bottom and the contraction of the width under the lip combine to give the impression of an elastic curvilinear rhythm to the generally ovoid form. -

Papyrus Bodmer XXVIII : a Satyr-Play on the Confrontation of Heracles and Atlas

Papyrus Bodmer XXVIII : a satyr-play on the confrontation of Heracles and Atlas Autor(en): Turner, Eric G. Objekttyp: Article Zeitschrift: Museum Helveticum : schweizerische Zeitschrift für klassische Altertumswissenschaft = Revue suisse pour l'étude de l'antiquité classique = Rivista svizzera di filologia classica Band (Jahr): 33 (1976) Heft 1 PDF erstellt am: 11.10.2021 Persistenter Link: http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-26396 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch MUSEUM HELVETICUM Vol. 33 1976 Fasc.l Papyrus Bodmer XXVIII: A Satyr-Play on the Confrontation of Heracles and Atlas By Eric G. Turner, London Dedicated to Bruno Snell, 80 years old June 1976 The fragments of a papyrus roll published and discussed in this paper were first seen by me in November 1972. -

Hesiod Theogony.Pdf

Hesiod (8th or 7th c. BC, composed in Greek) The Homeric epics, the Iliad and the Odyssey, are probably slightly earlier than Hesiod’s two surviving poems, the Works and Days and the Theogony. Yet in many ways Hesiod is the more important author for the study of Greek mythology. While Homer treats cer- tain aspects of the saga of the Trojan War, he makes no attempt at treating myth more generally. He often includes short digressions and tantalizes us with hints of a broader tra- dition, but much of this remains obscure. Hesiod, by contrast, sought in his Theogony to give a connected account of the creation of the universe. For the study of myth he is im- portant precisely because his is the oldest surviving attempt to treat systematically the mythical tradition from the first gods down to the great heroes. Also unlike the legendary Homer, Hesiod is for us an historical figure and a real per- sonality. His Works and Days contains a great deal of autobiographical information, in- cluding his birthplace (Ascra in Boiotia), where his father had come from (Cyme in Asia Minor), and the name of his brother (Perses), with whom he had a dispute that was the inspiration for composing the Works and Days. His exact date cannot be determined with precision, but there is general agreement that he lived in the 8th century or perhaps the early 7th century BC. His life, therefore, was approximately contemporaneous with the beginning of alphabetic writing in the Greek world. Although we do not know whether Hesiod himself employed this new invention in composing his poems, we can be certain that it was soon used to record and pass them on. -

Section Iii Greek and Roman Goddesses of Peace Contents Introduction Greek Goddesses of Peace and Harmony: Eirene and Harmonia R

SECTION III GREEK AND ROMAN GODDESSES OF PEACE CONTENTS INTRODUCTION GREEK GODDESSES OF PEACE AND HARMONY: EIRENE AND HARMONIA ROMAN GODDESSES OF PEACE AND CONCORDANCE: PAX AND CONCORDIA CLOSING COMMENTS ***** INTRODUCTION Lady Peace has many faces. Pinning down her attributes is no simple enterprise. The simplistic rendition is that Peace is the absence of War. But this definition does not outline how to end on-going war or how to prevent the start of war. The International Community set up peace-based global institutions, the League of Nations and United Nations, to prevent future war. Although both proved irresolute to prevent all wars, they were able to moderate some looming conflicts through the practices of peace-keeping and judicial mediation. There is a growing consensus among spirituality-oriented peace practitioners that the peace institutions that humanity needs will not be developed until humans establish a global system in which all peoples accept or submit to global authority. Until then nations are left to find their way through grievances and possible annihilation given the massive destruction of some of the existing weapon systems. What marks the Homo sapiens species special is its level of consciousness and its analytic thinking. But they are still insufficiently developed to coral the surge toward war (As this paragraph is being written war has broken out in Ethiopia’s Northern border.) Fortunately, humanity carries an archetypal template that points to how to address life issues such as peace. Dreams and mythology are places where the archetypal template projects itself. What follows is a brief review of Greek and Roman Peace Goddesses and their main companions. -

Apollo and His Purpose in Sophocles' Oedipus Tyrannus

APOLLO AND HIS PURPOSE IN SOPHOCLES’ OEDIPUS TYRANNUS Stuart Lawrence Abstract Apollo actively intervenes in the fulfilment of Oedipus’ destiny through oracles and immanently in the onstage action. Rather than to punish him for any offence, the god’s purpose appears to be to impress upon Oedipus his existential insignificance. In the context of an ordered but absurd universe, Sophocles emphasises the paradox of the moral greatness of a man whose ‘official’ existential value is less than zero. With the partial exception of Athena in the Ajax, Sophocles’ gods are largely inscruta‐ ble. In no play is this inscrutability more problematical than in the Tyrannus, and the resulting difficulties for the interpreter are well stated by R. Parker (1999), who warns us about drawing inferences where the poet is silent. Sensitive critics have always been struck by these silences of Sophocles’ text, of which the most famous is doubtless the apparent silence in Oedipus Tyrannus about the ulti‐ mate motivation for the destiny prophesied for Laius and Oedipus. In a sense the cen‐ tral problem for any study of Sophocles’ presentation of the divine is that of respond‐ ing to these silences: at all events, it is at this point that the paths of even the best critics diverge. Does Sophocles leave the divine will unexplained because to reason about it would be a distraction from the true human centre of the plays? Or is the point rather the ultimate incomprehensibility to mortals of the divine world? And if so, if the ways of the gods are incomprehensible, is that because those ways are good, but human comprehension weak? Or because mortals seek justice where none is to be found?1 Apollo never appears in person in the Tyrannus, though he declares his condition for the salvation of Thebes in the oracle that requires the discovery of Laius’ killer while he predicts the parricide in the original oracle to Laius and both the parricide and the incest in the later oracle given to Oedipus. -

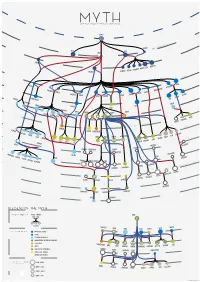

Legend of the Myth

MYTH Graph of greek mythological figures CHAOS s tie dei ial ord EREBUS rim p EROS NYX GAEA PONTU S ESIS NEM S CER S MORO THANATO A AETHER HEMER URANUS NS TA TI EA TH ON PERI IAPE HY TUS YNE EMNOS MN OC EMIS EANUS US TH TETHYS COE LENE PHOEBE SE EURYBIA DIONE IOS CREUS RHEA CRONOS HEL S EO PR NER OMETH EUS EUS ERSE THA P UMAS LETO DORIS PAL METIS LAS ERIS ST YX INACHU S S HADE MELIA POSEIDON ZEUS HESTIA HERA P SE LEIONE CE A G ELECTR CIR OD A STYX AE S & N SIPH ym p PA hs DEMETER RSES PE NS MP IA OLY WELVE S EON - T USE OD EKATH M D CHAR ON ARION CLYM PERSEPHONE IOPE NE CALL GALA CLIO TEA RODITE ALIA PROTO RES ATHENA APH IA TH AG HEBE A URAN AVE A DIKE MPHITRIT TEMIS E IRIS OLLO AR BIA AP NIKE US A IO S OEAGR ETHRA THESTIU ATLA S IUS ACRIS NE AGENOR TELEPHASSA CYRE REUS TYNDA T DA AM RITON LE PHEUS BROS OR IA E UDORA MAIA PH S YTO PHOEN OD ERYTHE IX EUROPA ROMULUS REMUS MIG A HESP D E ERIA EMENE NS & ALC UMA DANAE H HARMONIA DIOMEDES ASTOR US C MENELA N HELE ACLES US HER PERSE EMELE DRYOPE HERMES MINOS S E ERMION H DIONYSUS SYMAETHIS PAN ARIADNE ACIS LATRAMYS LEGEND OF THE MYTH ZEUS FAMILY IN THE MYTH FATHER MOTHER Zeus IS THEM CHILDREN DEMETER LETO HERA MAIA DIONE SEMELE COLORS IN THE MYTH PRIMORDIAL DEITIES TITANS SEA GODS AND NYMPHS DODEKATHEON, THE TWELVE OLYMPIANS DIKE OTHER GODS PERSEPHONE LO ARTEMIS HEBE ARES HERMES ATHENA APHRODITE DIONYSUS APOL MUSES EUROPA OSYNE GODS OF THE UNDERWORLD DANAE ALCEMENE LEDA MNEM ANIMALS AND HYBRIDS HUMANS AND DEMIGODS circles in the myth 196 M - 8690 K } {Google results M CALLIOPE INOS PERSEU THALIA CLIO 8690 K - 2740 K S HERACLES HELEN URANIA 2740 K - 1080 K 1080 K - 2410 J. -

Divine Riddles: a Sourcebook for Greek and Roman Mythology March, 2014

Divine Riddles: A Sourcebook for Greek and Roman Mythology March, 2014 E. Edward Garvin, Editor What follows is a collection of excerpts from Greek literary sources in translation. The intent is to give students an overview of Greek mythology as expressed by the Greeks themselves. But any such collection is inherently flawed: the process of selection and abridgement produces a falsehood because both the narrative and meta-narrative are destroyed when the continuity of the composition is interrupted. Nevertheless, this seems the most expedient way to expose students to a wide range of primary source information. I have tried to keep my voice out of it as much as possible and will intervene as editor (in this Times New Roman font) only to give background or exegesis to the text. All of the texts in Goudy Old Style are excerpts from Greek or Latin texts (primary sources) that have been translated into English. Ancient Texts In the field of Classics, we refer to texts by Author, name of the book, book number, chapter number and line number.1 Every text, regardless of language, uses the same numbering system. Homer’s Iliad, for example, is divided into 24 books and the lines in each book are numbered. Hesiod’s Theogony is much shorter so no book divisions are necessary but the lines are numbered. Below is an example from Homer’s Iliad, Book One, showing the English translation on the left and the Greek original on the right. When citing this text we might say that Achilles is first mentioned by Homer in Iliad 1.7 (i.7 is also acceptable). -

Aeschylus, Genealogy, History

SHADOWS ON THE SON: AESCHYLUS, GENEALOGY, HISTORY DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Richard Evan Rader Jr., M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2007 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Anthony Kaldellis, Adviser Professor Tom Hawkins _____________________________ Adviser Professor Bruce Heiden Greek and Latin Graduate Program ABSTRACT This dissertation examines genealogy and history in Prometheus Bound, Seven against Thebes, and Persians. It asks how a character‘s relation to his own family history affects his perspective on the past. I argue that in each play the conflict between a son and a father, say between Xerxes and Darius, is replicated at the level of a theory of history. Genealogy suggests two different relations between the past generations and the present, since it is both a reproduction of the same (the ideal son who takes after his father) and a production of difference (the son can never be identical to the father). These two genealogical relations correspond to two theories of history: what I identify as a retrospective view of history, which transfigures discrete historical events into teleology and inevitability, where history becomes the movement of necessity; and a prospective one, which sees historical events as only the trace of desire, hope, potential and human agency, where history becomes the movement of what could have been, the contingent unfolding of unlimited possibilities. In the Prometheus Bound, for example, Aeschylus stages the discord between Zeus and Prometheus as a conflict between two views on history: Prometheus leverages a secret about Zeus‘ sexual desire against him because he sees a necessity of repetition in Zeus‘ genealogical past; but Zeus, the play stresses, is fully capable of reason, compromise, and collaboration, and thus his future (unlike his predecessors‘) remains open to will, desire, and choice. -

Divine and Demonic Necessity in the Oresteia

Divine and Demonic Necessity in the Oresteia By CARL-MARTIN ED SMAN Aeschylus' religion' Aeschylus remains wholly within the context of the ancient religion. He forms his dramatical works with stern gravity and deep religiosity, so that a pervading piety is natural and there are no godless people. The archaic attitude of the poet appears not the least in his view of the departed. They are (as in Homer) bloodless shadows without emotions or perceptions (Agam. 568). But at the same time the murdered ones cry for vengeance, Nemesis rules over all and everything, and Dike looks after the right of the angered dead. The departed, therefore, have a dangerous power (Choeph. 479 ff., 315 ff.). When the earth has drunk the blood of a murdered person there is no turning back, even Zeus himself is then powerless (Eum. 647 ff., Choeph. 66 f.). The entire Oresteia is concerned with the necessity and the problem of blood-revenge, with retributive justice, but also—one must add— with atonement. The fickleness of fortune and the vanity of human life (Agam. 1237 ff.) in Aeschylus retreats, however, before the omnipotence of the gods. Koros creates hubris, and this, in its turn, atē, which is already in itself a punishment (Agam. 37o ff., Eum. 53o ff.). The envy of the gods, to be sure, is found also in Aeschylus, but at the same time the poet turns against the idea that great fortune leads to great misfortune (Agam. 75o ff.). An unrighteous act gives birth to misfortune, while a righteous house happily flourishes with children. -

The Rites in the Mysteries of Dionysus the Birth of the Drama

BRITT-MARI NÄSSTRÖM The Rites in the Mysteries of Dionysus The Birth of the Drama The Greek drama can be apprehended as an extended ritual, originating in the ceremonies of the Dionysus cult. In particular, tragedy derived its ori- gin from the sacrifice of goats and the hymns which were sung on that occasion. Tragedia means "song of the male goat" and these hymns later developed into choruses and eventually into tragedy, in the sense of a sol- emn and purifying drama. The presence of the god Dionysus is evident in the history and devel- opment of the Greek drama at the beginning of the fifth century B.C. and its sudden decline 150 years later. Its rise seems to correspond with the Greek polis, where questions of justice and divine law in conflict with the individual were obviously a matter of discussion and where the drama had individual and collective catharsis (purifying) in mind. In this respect Dionysus characterized the essence of the drama, by cross- ing and transgressing the border between the divine and the human world. When the gods interacted with men in the Homeric epics, they did so for their own selfish reasons, but in the classical drama they reflect and judge the activity of men. The drama thus reflects a change of paradigm from the world of myth to an ethical dialogue between men's world and the will of heaven. Dionysus was the god of intoxication and ecstasy and his followers were called maenads, from the Greek word mania, "madness". He was able to inspire his subjects with what was called enthusiasm, a word that still survives in a much milder sense. -

Hesiod As Precursor to the Presocratic Philosophers: a Voeglinian View

Hesiod as Precursor to the Presocratic Philosophers: A Voeglinian View Copyright 2001 Richard F. Moorton, Jr. Early in the Metaphysics Aristotle remarks that myth like philosophy begins in a sense of wonder (982b18f). For Voegelin mythology is that compact symbolization of the wondering psyche in testimony to its experience of the tension of existence in the world at the dawn of a people. A thinker like Herodotus, participating in the early stages of differentiation of the compact poesis of Greek mythology, still had a sense of the freshness of the achievements of the two fountainheads of Greek mythos, Homer and Hesiod: But it was only�if I may so put it�the day before yesterday�that the Greeks came to know the origin and form of the various Gods, and whether or not all of them had always existed; for Homer and Hesiod, the poets who composed our theogonies and described the gods for us, giving them their appropriate titles, offices, and powers, lived, as I believe, not more than four hundred years ago. But Voegelin correctly discerns in both Homer and Hesiod the seminal impulses of protophilosophers of order. Homer is the great diagnostician of nosos, sickness, in the social order of what he took to be Achaean society and in the human conception of the divine order. Though prephilosophical, he is nonetheless a great poet of the movement of the psyche towards truth and its possible derailment in disorder, a philosopher�s concern. Hesiod disentangles this poisesis from the specific "true story" of the Trojan conflict and universalizes it in his Theogony, a theological cosmology, and the Works and Days, a theosensitive anthropology. -

Late-Stage Intrusive Activity at Olympus Mons

LATE-STAGE INTRUSIVE ACTIVITY AT OLYMPUS MONS, MARS: SUMMIT INFLATION AND GIANT DIKE FORMATION Peter J. Mouginis-Mark1* and Lionel Wilson2 1Hawaii Institute of Geophysics and Planetology University of Hawaii Honolulu, Hawaii 96822 USA 2Lancaster Environment Centre Lancaster University Lancaster LA1 4YQ UK Icarus In press, September 2018 Keywords: Mars Olympus Mons Ascraeus Mons Volcanic dikes 1 Abstract 2 By mapping the distribution of 351 lava flows at the summit area of Olympus Mons 3 volcano on Mars, and correlating these flows with the current topography from the Mars 4 Orbiter Laser Altimeter (MOLA), we have identified numerous flows which appear to have 5 moved uphill. This disparity is most clearly seen to the south of the caldera rim, where the 6 elevation increases by >200 m along the apparent path of the flow. Additional present day 7 topographic anomalies have been identified, including the tilting down towards the north 8 of the floors of Apollo and Hermes Paterae within the caldera, and an elevation difference 9 of >400 m between the northern and southern portions of the floor of Zeus Patera. We 10 conclude that inflation of the southern flank after the eruption of the youngest lava flows 11 is the most plausible explanation, which implies that intrusive activity at Olympus Mons 12 continued towards the present beyond the age of the youngest paterae ~200 – 300 Myr 13 (Neukum et al., 2004; Robbins et al., 2011). We propose that intrusion of lateral dikes to 14 radial distances >2,000 km is linked to the formation of the individual paterae at Olympus 15 Mons.