Midlands State University Faculty of Arts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

As a Child You Have No Way of Knowing How Fast Or Otherwise The

A FOREIGN COUNTRY: GROWING UP IN RHODESIA Nigel Suckling Draft: © January 2021 1 I – MUNALI – 5 II – LIVINGSTONE – 43 III – PARALLEL LIVES – 126 IV – LUSAKA – 212 V – GOING HOME – 244 APPENDIX – 268 2 FOREWORD As a child you have no measure of how fast the world around you is changing. Because you’re developing so quickly yourself, you assume your environment is static and will carry on pretty much the same as you grow into it. This is true for everyone everywhere, naturally. Most old people can, if suitably primed, talk indefinitely about the changes they’ve seen in their lifetimes, even if they’ve never moved from the place where they were born; but some environments change more drastically than others, even without a war to spur things along. One such was Northern Rhodesia in southern Africa in the 1950s and 60s. As white kids growing up then we had no way of knowing, as our parents almost certainly did, just how fragile and transient our conditions were – how soon and how thoroughly the country would become Zambia, with a completely different social order and set of faces in command. The country of course is still there. In many ways its urban centres now look remarkably unchanged due to relative poverty. The houses we grew up in, many of the streets, landmark buildings and landscapes we were familiar with are still recognizably the same, much more so in fact than in many parts of Europe. What has vanished is the web of British colonial superstructure into which I and my siblings were born as privileged members, brief gentry on the cusp of a perfectly justified and largely peaceful revolution that was soon to brush us aside. -

32Nd Edition ANNUAL REPORT

EZI RI MB VE A R Z ZAMBEZI RIVER AUTHORITY 32nd Edition ANNUAL and Financial Statements for the year ended REPORT 31st December 2019 2019 ANNUAL REPORT 2019 CONTACT INFORMATION LUSAKA OFFICE (Head Office) HARARE OFFICE KARIBA OFFICE Kariba House 32 Cha Cha Cha Road Club Chambers Administration Block P.O. Box 30233, Lusaka Zambia Nelson Mandela Avenue 21 Lake Drive Pvt. Bag 2001, Tel: +260 211 226950, 227970-3 P.O. Box 630, Harare Zimbabwe Kariba Zimbabwe Fax: +260 211 227498 Telephone: +263 24 2704031-6 Tel: +263 261 2146140/179/673/251 e-mail: [email protected] VoIP:+263 8677008291 :+263 VoIP:+2638677008292/3 Web: http://www.zambezira.org/ 8688002889 e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] The outgoing EU Ambassador Alessandro Mariani with journalists on a media tour of the KDRP ZAMBEZI RIVER AUTHORITY | 2 ANNUAL REPORT 2019 CONTENTS MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIRPERSON ........................................................................4 ZAMBEZI RIVER AUTHORITY PROFILE .......................................................................8 COUNCIL OF MINISTERS ............................................................................................10 BOARD OF DIRECTORS ..............................................................................................11 EXECUTIVE MANAGEMENT .......................................................................................14 OPERATIONS REPORTS .............................................................................................16 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS ...........................................................................................51 -

The Kariba REDD+ Project CCBS Project Design Document (PDD)

The Kariba REDD+ project CCBS Project design document (PDD) Developed by: Tilmann Silber South Pole Carbon Asset Management Version 1 Date: October 13, 2011 For validation using the Climate, Community & Biodiversity Standard (CCBS), Second Edition, December 2008. Contents I. Basic Data 3 II. General Section 3 G1. Original Conditions in the Project Area 3 G2. Baseline Projections 21 G3. Project Design and Goals 24 G4. Management Capacity and Best Practices 35 G5. Legal Status and Property Rights 40 III. Climate Section 44 CL1. Net Positive Climate Impacts 44 CL2. Offsite Climate Impacts (‘Leakage’) 47 CL3. Climate Impact Monitoring 48 IV. Community Section 51 CM1. Net Positive Community Impacts 51 CM2. Offsite Stakeholder Impacts 52 CM3. Community Impact Monitoring 53 V. Biodiversity Section 57 B1. Net Positive Biodiversity Impacts 57 B2. Offsite Biodiversity Impacts 60 B3. Biodiversity Impact Monitoring 60 V. Gold Level Section 62 GL1. Climate Change Adaptation Benefits 62 GL2. Exceptional Community Benefits 64 GL3. Exceptional Biodiversity Benefits 66 Annex 1: Biodiversity Information 68 Annex 2: Grievance Procedure 74 2 CCBA PROJECT DESIGN DOCUMENT FORM FOR PROJECT ACTIVITIES (CCBA-PDD) Version 01 I. Basic Data 1) The title of the CCB Standards project activity: Kariba REDD+ project 2) The version number of the document: Version 1 3) The date of the document: October 13, 2011 II. General Section G1. Original Conditions in the Project Area General information G1.1 The location of the project and basic physical parameters (e.g., soil, geology, climate). Location The Kariba REDD+ project is located in northwestern Zimbabwe, partly along the southern shore of Lake Kariba, the largest artificial lake in the world by volume. -

Lake Kariba Fisheries Research Institute Project Report Number 67

Annual report 1990 Item Type monograph Authors Machena, C. Publisher Department of National Parks and Wild Life Management Download date 29/09/2021 15:18:38 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/25005 Lake Kariba Fisheries Research Institute Project Report Number 67 1990 Annual Report Compiled by C. Machena ,ional Parks and Wildlife Management. COMMITTEE OF MANAGEMENT MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT AND TOURISM Mr K.R. Mupfumira - Chief Executive Officer DEPARTMENT OF NATIONAL PARKS AND WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT Dr. W.K. Nduku - Director and Chairman of Committee of Management Mr. G. Panqeti - Deputy Director Mr.R.B. Martin - Assistant Director (Research) Mr. Nyamayaro - Assistant Director (Administration) LAKE KARIBA FISHERIES RESEARCH INSTITUTE Dr. C. Machena - Officer - in - Charge Mr. N. Mukome - ExecutiveOfficer and Secretary of Committee of Management. TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Officer-in-Charge's Reoort 4 The Zambia/Zimbabwe SADCC Lake Kariba Fisheries Research And DeveloQment Pro:iect 12 Comparative Study Of Growth OfLimnothrissanijodon (Boulenger) in Lake Kariba 18 An Analysis Of The Effects Of Fishing Location And Gear On Kapenta Catches On Lake Kariba 19 Hydro-acoustic Surveys In Lake Kariba 20 The Pre-recruitment Ecology of The Freshwater SardineLimnothrissamíodon(Boulenger) In Lake Kariba 22 Report On Short Course In Zooplankton Quantitative Sampling Methods held at the Freshwater Biology Laboratory Windermere From 19 to 30 November 1990... 25 Report On Training: Post-Graduate Training - Humberside Polytechnic, U.K 32 Postharvest Fish Technology In Lake Kariba. Zimbabwe 33 Assessment Of The Abundance Of Inshore Fish Stocks And Evaluating The Effects Of Fishing Pressure On The Biology Of Commercially Important Species And Ecological Studies OnSynodontiszambezensís.......35 11. -

Download Trip Planner

Deluxe African Wildlife Safari Zimbabwe & Botswana, Africa ~ Victoria Falls ~ Wildlife Viewing ~ ~ National Parks ~ Sunset Cruise ~ Exotic Cuisine ~ Table of Contents Trip Summary ........................................................................................................... 3 Accommodations ...................................................................................................... 3 Itinerary in Detail ...................................................................................................... 4 Flying In and Out ..................................................................................................... 7 Packing List ............................................................................................................... 7 Money Matters .......................................................................................................... 8 Immunizations .......................................................................................................... 9 Water ........................................................................................................................ 10 Food ......................................................................................................................... 10 Digestive Worries ................................................................................................... 10 Prescriptions ............................................................................................................ 10 Voltage .................................................................................................................... -

Download Malawi, Zambia & Zimbabwe Detailed

Malawi, Zambia & Zimbabwe Detailed Itinerary Oct 09/19 Experience a part of Africa that does not get the Facts & Highlights crowds but could easily be considered some of • 22 days • Maximum 16 travelers • Start in Lilongwe, Malawi and finish in Victoria Falls, Africa’s greatest gems - Malawi, Zambia and Zim- Zimbabwe • All meals included) • Includes 2 babwe! Superb game viewing, ancient ruins, local internal flights • Feel the thunder of Victoria village encounters including school visits, a sunset Falls (UNESCO) • Explore Great Zimbabwe ruins (UNESCO) • Enjoy game drives in Hwange, cruise on the Zambezi, and of course, the thunder Matobo (UNESCO), Matusadona N.P., South of Victoria Falls make this an exhilarating African Luangwa N.P., Lake Malawi• Enjoy visits to local journey. villages and schools Departure Dates & Price In Malawi, explore the capital city of Lilongwe Apr 03 - Apr 24, 2020 - $9995 USD before our journey takes us to Cape Maclear, Lake Oct 26 - Nov 16, 2020 - $9995 USD Malawi and Liwande National Parks, with its excel- Mar 15 - Apr 05, 2021 - $10995 USD Sep 25 - Oct 16, 2021 - $10995 USD lent wildlife viewing. Activity Level: 2 In Zambia, enjoy safaris in South Luangwa and Comfort Level: Lower Zambezi National Parks, keeping an eye out Some long drives and unpaved roads, espe- for elephant, buffalo, hippo, crocodile, lion, hyena, cially during safaris. Temperatures can be very hot. leopard and wild dog. We fly to Lusaka were we have Accommodations our urban exploration of the capital city. Comfortable hotels/lodges with private Impressive Victoria Falls is perhaps Zimbabwe’s bathrooms for all nights. -

An Encroachment of Ecological Sacred Sites and Its Threat to the Interconnectedness of Sacred Rituals: a Case Study of the Tonga People in the Gwembe Valley

An Encroachment of Ecological Sacred Sites and its Threat to the Interconnectedness of Sacred Rituals: A Case Study of the Tonga People in the Gwembe Valley Lilian Siwila [email protected] Abstract The problem of encroaching sacred sites is one of the biggest challenges most developing countries face. In the name of development people’s sacred sites and rituals are either destroyed or relocated to other sites. This paper uses two cases to discuss the value of sacred sites and sacred rituals and their religious connectivity to Tonga ecology. The paper begins with a brief discussion on the Tonga ecology and the effects of the construction of the Kariba dam in the 1950s to local people’s religiosity, worldviews and perceptions of environmental issues. Thereafter the paper deals with another ecological practice of the Tonga people called lwiindi ceremony. Within this practice the paper employs gender lens to analyse the value of religion in the practice and how the practice is slowly being trespassed by political interests thus overriding its significance to peoples’ understating of crop production and rain patterns. This study has found out that indigenous peoples’ religion is embedded in their understating of ecological sites and rituals. Therefore development programmes working in these spaces need to take into consideration the religious significance attached to these sites by the local people. This will help enhance environmental care and respect for people’s religious beliefs and spiritualties. This however does not mean romanticising indigenous knowledge as though it has no ecological challenges. Keywords: Sacred Sites, Tonga Rituals, Ecology, Religion, development, lwiindi Journal for the Study of Religion 28,2 (2015) 138 - 153 138 ISSN 1011-7601 Ecological Sacred Sites and the Interconnectedness of Sacred Rituals Introduction A 30th May 2014 Aljezeera news report by Tania read, ‘there were fears that the Kariba dam had a crack on the walls which was likely to cause massive destruction once the dam opened up. -

A Comparitive Analysis of Afrofuturism, Magical Realism And

A COMPARITIVE ANALYSIS OF AFROFUTURISM, MAGICAL REALISM AND AFRICAN MYTHOLOGY IN NAMWALI SERPELL’S THE OLD DRIFT AND MARLON JAMES’S BLACK LEOPARD RED WOLF: AN AFROCENTRIC PERSPECTIVE RESEARCH PROPOSAL SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FUFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ENGLISH STUDIES OF UNIVERSITY OF NAMIBIA BY MASIYALETI MBEWE 201056925 APRIL 2021 Supervisor: Dr C. Sabao ABSTRACT Afrofuturism, Magical Realism and African Mythology are genres in literary fiction that can be used by authors and writers to explore difficult themes, complex characters, speculative settings and experimental plot points. While studies of these genres in literature exist, there has not been sufficient research in these concepts that centre the African perspective or explore the intersections of these genres. The main objective of this study was to investigate how Afrofuturism, Magical Realism and African Mythology are applied in the novels The Old Drift by Namwali Serpell and Black Leopard Red Wolf by Marlon James, to provide an analysis, explore new methods of theorising African literature and challenge current literary epistemologies. This study used the Afrocentric theoretical framework developed by Asante (1980) to meet said objectives and contextualise the analysis of the two novels. One of the main findings of this research outlined how instrumental Afrofuturism, Magical Realism and African Mythology are as literary genres in African literature as they allow authors to centre African perspectives. These perspectives thereby help cultivate a distinct lens that prioritises the African reader. Furthermore, the genres under investigation proved to be a resourceful way for African narratives immerging from the continent to explore a magnitude of complex themes. -

Malawi, Zambia & Zimbabwe

Malawi, Zambia & Zimbabwe Detailed Itinerary May 29/19 Experience a part of Africa that does not get the Facts & Highlights crowds but could easily be considered some of • 22 days • Maximum 16 travelers • Start in Lilongwe, Africa’s greatest gems - Malawi, Zambia and Zim- Malawi and finish in Victoria Falls, Zimbabwe • All meals included) • Includes 2 internal flights • Feel the thunder babwe! Superb game viewing, ancient ruins, local of Victoria Falls (UNESCO) • Explore Great Zimbabwe village encounters including school visits, a sunset ruins (UNESCO) • Enjoy game drives in Hwange, Matobo (UNESCO), Matusadona N.P, South Luangwa N.P, Lake cruise on the Zambezi, and of course, the thunder Malawi N.P., Lower Zambezi N.P. • Enjoy visits to local of Victoria Falls make this an exhilarating African villages and schools journey. Departure Dates & Price In Malawi, explore the capital city of Lilongwe Oct 04 - Oct 25, 2019 - $9995 USD Apr 03 - Apr 24, 2020 - $9995 USD before our journey takes us to Cape Maclear, Lake Oct 06 - Oct 27, 2020 - $9995 USD Malawi and Liwande National Parks, with its excel- Activity Level: 2 lent wildlife viewing. Comfort Level: In Zambia, enjoy safaris in South Luangwa and Some long drives and unpaved roads, especially during safaris. Temperatures can be very hot. Lower Zambezi National Parks, keeping an eye out Accommodations for elephant, buffalo, hippo, crocodile, lion, hyena, Comfortable hotels/lodges with private bathrooms leopard and wild dog. We fly to Lusaka were we have for all nights. our urban exploration of the capital city. Impressive Victoria Falls is perhaps Zimbabwe’s most famous site but Zimbabwe has so much more to offer. -

An Exploration of the Causes of Social Unrest in Omay Communal Lands of Nyami Nyami District in Zimbabwe: a Human Needs Perspective

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by South East Academic Libraries System (SEALS) AN EXPLORATION OF THE CAUSES OF SOCIAL UNREST IN OMAY COMMUNAL LANDS OF NYAMI NYAMI DISTRICT IN ZIMBABWE: A HUMAN NEEDS PERSPECTIVE MAMBO MUSONA JAN.2011 DEPARTMENT OF ACADEMIC ADMINISTRATION EXAMINATION SECTION SUMMERSTARND NORTH CAMPUS PO Box 77000 Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University Port Elizabeth 6013 Enquiries: Postgraduate Examination Officer DECLARATION BY CANDIDATE NAME: MAMBO MUSONA STUDENT NUMBER: S209080245 QUALIFICATION: MPhil. CONFLICT MANAGEMENT AND TRANSFORMATION TITLE OF ROJECT: AN EXPLORATION OF THE CAUSES OF SOCIAL UNREST IN OMAY COMMUNAL LANDS OF NYAMI NYAMI DISTRICT OF ZIMBABWE: A HUMAN NEEDS PERSPECTIVE. DECLARATION: In accordance with Rule G4.6.3, I hereby declare that the above-mentioned treatise/ dissertation/ thesis is my own work and that it has not previously been submitted for assessment to another University or for another qualification. SIGNATURE: Mambo Musona DATE: 07 JAN. 2011 ii Acknowledgement Sincere gratitude and appreciation is extended to various persons who assisted me, through their commitment to make this research a success and their tolerance of the demands it placed on them. To this end, I would like to thank most sincerely the following: Dr Gavin Bradshaw, my supervisor, for the guidance, advice and support that made completing this treatise possible. • Silveira House for the material and transport support to reach the study area. • Chiefs Mola and Negande for providing accommodation and cultural guidance. • All the respondents in Omay • C. Ukurut, fellow student for the moral support and courage throughout the process. -

Cop14 Prop. 6

CoP14 Prop. 6 CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA ____________________ Fourteenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties The Hague (Netherlands), 3-15 June 2007 CONSIDERATION OF PROPOSALS FOR AMENDMENT OF APPENDICES I AND II A. Proposal 1. Amendment of the annotation regarding the populations of Loxodonta africana of Botswana, Namibia and South Africa to: a) include the following provision: "No trade in raw or worked ivory shall be permitted for a period of 20 years except for: 1) raw ivory exported as hunting trophies for non-commercial purposes; and 2) ivory exported pursuant to the conditional sale of registered government-owned ivory stocks agreed at the 12th meeting of the Conference of the Parties."; and b) remove the following provision: "6) trade in individually marked and certified ekipas incorporated in finished jewellery for non-commercial purposes for Namibia". 2. Amendment of the annotation regarding the population of Loxodonta africana of Zimbabwe to read: "For the exclusive purpose of allowing: 1) export of live animals to appropriate and acceptable destinations; 2) export of hides; and 3) export of leather goods for non-commercial purposes. All other specimens shall be deemed to be specimens of species included in Appendix I and the trade in them shall be regulated accordingly. No trade in raw or worked ivory shall be permitted for a period of 20 years. To ensure that where a) destinations for live animals are to be appropriate and acceptable and/or b) the purpose of the import -

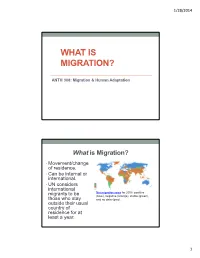

What Is Migration?

1/28/2014 WHAT IS MIGRATION? ANTH 308: Migration & Human Adaptation What is Migration? • Movement/change of residence. • Can be internal or international. • UN considers international Net migration rates for 2008: positive migrants to be (blue), negative (orange), stable (green), those who stay and no data (gray). outside their usual country of residence for at least a year. 1 1/28/2014 This map shows proportion of world’s international emigrants coming from each territory. International Emigrants The territory size shows the number of international immigrants that live there. International Immigrants 2 1/28/2014 3 1/28/2014 4 1/28/2014 5 1/28/2014 Migration Number of migrants doubled between 1945-2005. In 2005, 191 million people were living outside country of their birth. If they all lived in same place, these international migrants would form 5th most populous country in world . Who is a migrant? • There is no one, single accepted definition. • 2 key issues are Group of Florida migrants on their way to Cranberry, New Jersey, to pick potatoes. usually identified: Near Shawboro, North Carolina. 1940. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/fsa200002 1. Degree of 2264/PP/ The Great Migration was the movement of 6 permanence . million African Americans out of the rural Southern United States to the urban Length of time person has Northeast , Midwest , and West that lasted up spent or will spend in new until the 1960s. Some historians differentiate between the first Great Migration (1910–1930), locale. numbering about 1.6 million migrants who left mostly rural areas to migrate to northern 2.