Managing the Pentagon's International Relations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vojenské Reflexie

ROČNÍK IV. ČÍSLO 1/2009 Akadémia ozbrojených síl generála Milana Rastislava Štefánika VEDECKO-ODBORNÝ ČASOPIS ROČNÍK IV. ČÍSLO 1/2009 2 AKADÉMIA OZBROJENÝCH SÍL GENERÁLA MILANA RASTISLAVA ŠTEFÁNIKA LIPTOVSKÝ MIKULÁŠ, 2009 Redakčná rada / Editorial board / vedecko-odborného časopisu AOS od 1. júna 2009 Čestný predseda: brig. gen. Ing. Marián ÁČ, PhD., náčelník Vojenskej kancelárie prezidenta SR Predseda: doc. Ing. Pavel BUČKA, CSc., prorektor pre vzdelávanie AOS GMRŠ Členovia: brig. gen. doc. Ing. Miroslav KELEMEN, PhD., rektor AOS GMRŠ plk. gšt. doc. Ing. Pavel NEČAS, PhD., prorektor pre vedu AOS GMRŠ plk. gšt. Ing. Ján PŠIDA, Stála delegácia SR pri NATO/EÚ Brusel Dr. Boleslav SPRENGL, rektor Wyzsa Szkola Bezpieczeństwa i Ochrony, Warszawa prof. Ing. Václav KRAJNÍK, CSc., prorektor pre vedu a zahraničné vzťahy Akadémie PZ Bratislava prof. Ing. Jozef HALÁDIK, PhD., prorektor pre vzdelávanie a rozvoj Akadémie PZ Bratislava Dr. h. c. prof. Ing. Marián MESÁROŠ, CSc., rektor VŠBM Košice prof. Ing. Vladimír SEDLÁK, CSc., prorektor pre vedu a zahraničné vzťahy VŠBM Košice prof. nadzw. dr. hab. Stanislav ZAJAS, prorektor pre vzdelávanie AON, Warszawa genmjr. v. v. Ing. Rudolf ŽÍDEK, vedúci KNB AOS GMRŠ doc. Ing. Radovan SOUŠEK, PhD., Univerzita Pardubice, ČR plk. nawig. dr. inž. Marek GRZEGORZEWSKI, WSOSP Deblin, Poland doc. Ing. Stanislav SZABO, PhD. mim. prof. , LF TU Košice doc. Ing. František ADAMČÍK, PhD., prodekan pre pedagogickú činnosť LF TU Košice plk. doc. Ing. Peter SPILÝ, PhD., vedúci Ústavu bezpečnosti AOS GMRŠ Šéfredaktor: Mgr. Silvia CIBÁKOVÁ, AOS GMRŠ Adresa redakcie/editorial board: Akadémia ozbrojených síl generála Milana Rastislava Štefánika Demänovská cesta č. 393 031 01 Liptovský Mikuláš tel. -

A Case Study of Executive Military Leadership

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE STRATEGIC BEACON IN THE FOG OF LEADERSHIP: A CASE STUDY OF EXECUTIVE MILITARY LEADERSHIP OF THE IRAQ SURVEY GROUP A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By ROY J. PANZARELLA Norman, Oklahoma 2006 i UMI Number: 3207186 Copyright 2006 by Panzarella, Roy J. All rights reserved. UMI Microform 3207186 Copyright 2006 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 STRATEGIC BEACON IN THE FOG OF LEADERSHIP: A CASE STUDY OF EXECUTIVE MILITARY LEADERSHIP OF THE IRAQ SURVEY GROUP A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE GRADUATE COLLEGE By ____________________________ Dr. Gary Copeland ____________________________ Dr. Jerry Weber ____________________________ Dr. H. Dan O’Hair ____________________________ Dr. Keith Gaddie ____________________________ Dr. Russell Lucas i © Copyright by ROY J. PANZARELLA 2006 All Rights Reserved i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the magnificent staff and faculty of the University of Oklahoma for their vision, dedication and hard work helping cohort members turn their dreams into realities. Special thanks to my dissertation committee, but especially the chair, Dr. Gary Copeland, for his professionalism, time, mentorship, friendship and encouragement. I would like to express my gratitude to American military members and their families for their bravery, selfless service and sacrifices at home and on foreign battlefields, principally the men and women from the interagency who served honorably in the Iraq Survey Group. -

Gunn Cover Sheet Escholarship.Indd

America and the Misshaping of a New World Order Edited by Giles Gunn and Carl Gutiérrez-Jones Published in association with the University of California Press “An important and telling critique of the myth and rhetoric of con- temporary American expansionism and grand strategy. What is par- ticularly original about these essays—and unusually rare in studies of American foreign policy—is their provocative combination of cultural and literary analysis with a subtle appreciation of the historical trans- formation of political forms and principles of world order.” STEPHEN GILL, author of Power and Resistance in the New World Order The attempt by the George W. Bush administration to reshape world order, especially but not exclusively after September 11, 2001, increasingly appears to have resulted in a catastrophic “misshaping” of geo- politics in the wake of bungled campaigns in the Middle East and their many reverberations worldwide. Journalists and scholars are now trying to understand what happened, and this volume explores the role of culture and rhetoric in this process of geopolitical transformation. What difference do cultural con- cepts and values make to the cognitive and emotional weather of which, at various levels, international politics is both consequence and perceived corrective? The distinguished scholars in this multidisci- plinary volume bring the tools of cultural analysis to the profound ongoing debate about how geopolitics is mapped and what determines its governance. GILES GuNN is Professor and Chair of Global and International Studies and Professor of English at the University of California, Santa Barbara. cArL GuTIérrEz-JONES is Professor of English and Director of the Chicano Studies Institute at the University of California, Santa Barbara. -

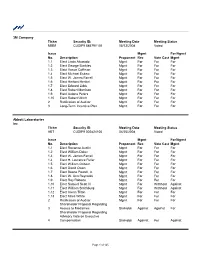

3M Company Ticker Security ID: MMM CUSIP9 88579Y101 Issue No

3M Company Ticker Security ID: Meeting Date Meeting Status MMM CUSIP9 88579Y101 05/13/2008 Voted Issue Mgmt For/Agnst No. Description Proponent Rec Vote Cast Mgmt 1.1 Elect Linda Alvarado Mgmt For For For 1.2 Elect George Buckley Mgmt For For For 1.3 Elect Vance Coffman Mgmt For For For 1.4 Elect Michael Eskew Mgmt For For For 1.5 Elect W. James Farrell Mgmt For For For 1.6 Elect Herbert Henkel Mgmt For For For 1.7 Elect Edward Liddy Mgmt For For For 1.8 Elect Robert Morrison Mgmt For For For 1.9 Elect Aulana Peters Mgmt For For For 1.10 Elect Robert Ulrich Mgmt For For For 2 Ratification of Auditor Mgmt For For For 3 Long-Term Incentive Plan Mgmt For For For Abbott Laboratories Inc Ticker Security ID: Meeting Date Meeting Status ABT CUSIP9 002824100 04/25/2008 Voted Issue Mgmt For/Agnst No. Description Proponent Rec Vote Cast Mgmt 1.1 Elect Roxanne Austin Mgmt For For For 1.2 Elect William Daley Mgmt For For For 1.3 Elect W. James Farrell Mgmt For For For 1.4 Elect H. Laurance Fuller Mgmt For For For 1.5 Elect William Osborn Mgmt For For For 1.6 Elect David Owen Mgmt For For For 1.7 Elect Boone Powell, Jr. Mgmt For For For 1.8 Elect W. Ann Reynolds Mgmt For For For 1.9 Elect Roy Roberts Mgmt For For For 1.10 Elect Samuel Scott III Mgmt For Withhold Against 1.11 Elect William Smithburg Mgmt For Withhold Against 1.12 Elect Glenn Tilton Mgmt For For For 1.13 Elect Miles White Mgmt For For For 2 Ratification of Auditor Mgmt For For For Shareholder Proposal Regarding 3 Access to Medicines ShrHoldr Against Against For Shareholder Proposal Regarding Advisory Vote on Executive 4 Compensation ShrHoldr Against For Against Page 1 of 125 Accenture Limited Ticker Security ID: Meeting Date Meeting Status ACN CUSIP9 G1150G111 02/07/2008 Voted Issue Mgmt For/Agnst No. -

SHAPE Officers' Association Newsletter February 2012

SHAPE Officers’ Association Newsletter February 2012 RECENT EVENTS AND HAPPENINGS 1. 51st SOA Symposium and Reunion – SHAPE The 51st Reunion/Symposium was held 13-14 October 2011 in Casteau, Belgium. The agenda included: Thursday 13 Oct Executive Committee (henceforth ExCom) meeting and Welcome Reception at Casteau Resort Hotel Friday 14 Oct General Assembly No Host Dinner at Ecole Provinciale d’Hotellerie Summary of Events: On Thursday, 13 October, and Friday, 14 October, the SHAPE Officers’ Association held its Annual Symposium at SHAPE. It was the 51st occasion for former and present SHAPE Officers and their civilian equivalents to meet, exchange ideas and be informed about the present engagements of NATO and SHAPE. This year’s meeting had fewer participants than last year’s 50th symposium, but the Executive Committee organized an attractive and interesting program. It was especially important, because the SOA and the ExCom had during the past year attempted to modernize the organization and adjust its aims and goals to the important developments and changes SHAPE and NATO had undergone during the last years. The symposium started on Thursday afternoon with a meeting of the ExCom and the representatives of the American and German Chapters. Last minute adjustments were made to the agenda to be discussed during the General Assembly on Friday. After this important meeting, the members who had arrived from various countries in Europe and North America enjoyed a Happy Hour to renew old friendships and make new ones. Happy Hour was held in the Casteau Resort Hotel, where many of the members were lodged. The main event started Friday morning in the SHAPE Club with the General Assembly. -

Integrating Instruments of Power and Influence Lessons Learned and Best Practices

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available from www.rand.org as a public CHILD POLICY service of the RAND Corporation. CIVIL JUSTICE EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS NATIONAL SECURITY The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit research POPULATION AND AGING organization providing objective analysis and effective PUBLIC SAFETY solutions that address the challenges facing the public SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY and private sectors around the world. SUBSTANCE ABUSE TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Support RAND Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND National Security Research Division View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation conference proceedings series. RAND conference proceedings present a collection of papers delivered at a conference or a summary of the conference. The material herein has been vetted by the conference attendees and both the introduction and the post-conference material have been re- viewed and approved for publication by the sponsoring research unit at RAND. -

Brintnall, Clarke Mccurdy

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project BRIGADIER GENERAL CLARKE MCCURDY BRINTNALL Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: May 2, 1996 Copyright 1998 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Born and raised in Omaha, Nebraska West Point graduate, 1958 U.S. Army Signal Corps, Darmstadt, Germany Soviet ,atching TD- mobile communications in .ran Fort Monmouth, N0. Signal Officer Course ST1.2E Command, MacDill AFB 194151942 Cuba crisis Army 7anguage School, Monterey 194251948 Portuguese Bra9il, 1io de 0aneiro 194851945 7anguage student Political and social environment Anti5Americanism English language instructor at Staff College US A.D :ernon Walters Panama 194451949 Cuba Special Forces Terrorism5regional Area responsibility of M.7G1Ps F55s Ft. Holabird, MD 194951970 .ntelligence school :ietnam 194951970 First Cavalry Division 1 :iet Cong capabilities A1:A capabilities Armed Forces Staff College 1971 0oint Chiefs of Staff Assignments 197151978 American Defense Board 0oint Bra9il5US Defense Commission US5Mexico Military Commission Bra9il, Brasilia 197851977 Assistant Army Attaché uclear safeguards issues Human rights issues Bra9il abrogates US military agreement Argentine concerns Environment Army War College 197751978 Defense Department, .SA 197851983 7atin American issues Cuba icaragua and Sandinistas Maldive issue Bra9il@s nuclear and space programs aval Unitas exercise Colombia cooperation Mexico@s attitude F51s and 7atin America Soviet arms programs in 7ain America U.S. Training and Doctrine Command Guantanamo Bay Bra9il, Brasilia 198351985 Attaché Ama9on developments 1elations ,ith Bra9ilians Bra9ilian military arcotics problems Defense .ntelligence Agency 198551984 Director for Attachés and Operations Selecting attachés Soviet Union Aattachés in) 2 Defense Department, .SA 198451988 Director of .nter5American 1egions Duties and responsibilities .ran CContra affair oriega Argentine relations Grenada invasion arcotics 1etirement 1988 ational Security Council 198851989 Panama Gen. -

Download File

Limited Liability Multilateralism: The American Military, Armed Intervention, and IOs Stefano Recchia Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2011 © 2011 Stefano Recchia All rights reserved ABSTRACT Limited Liability Multilateralism: The American Military, Armed Intervention, and IOs Stefano Recchia Under what conditions and for what reasons do American leaders seek the endorsement of relevant international organizations (IOs) such as the UN or NATO for prospective military interventions? My central hypothesis is that U.S. government efforts to obtain IO approval for prospective interventions are frequently the result of significant bureaucratic deliberations and bargaining between hawkish policy leaders who emphasize the likely positive payoffs of a prompt use of force, on the one side, and skeptical officials—with the top military brass and war veterans in senior policy positions at the forefront—who highlight its potential downsides and long-term costs, on the other. The military leaders—the chairman and vice chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS), the regional combatant commanders, and senior planners on the Joint Staff in Washington—are generally skeptical of humanitarian and other ―idealist‖ interventions that aim to change the domestic politics of foreign countries; they naturally tend to consider all the potential downsides of intervention, given their operational focus; and they usually worry more than activist civilian policy officials about public and congressional support for protracted engagements. Assuming that the military leaders are not merely stooges of the civilian leadership, they are at first likely to altogether resist a prospective intervention, when they believe that no vital American interests are at stake and fear an open-ended deployment of U.S. -

Report of the Independent Commis- Sion on the Security Forces of Iraq

i [H.A.S.C. No. 110–88] REPORT OF THE INDEPENDENT COMMIS- SION ON THE SECURITY FORCES OF IRAQ COMMITTEE ON ARMED SERVICES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION HEARING HELD SEPTEMBER 6, 2007 U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 37–733 WASHINGTON : 2008 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 22-MAR-2001 08:46 Oct 07, 2008 Jkt 037733 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5012 Sfmt 5012 C:\DOCS\110-88\249000.000 HNS1 PsN: HNS1 HOUSE COMMITTEE ON ARMED SERVICES ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS IKE SKELTON, Missouri, Chairman JOHN SPRATT, South Carolina DUNCAN HUNTER, California SOLOMON P. ORTIZ, Texas JIM SAXTON, New Jersey GENE TAYLOR, Mississippi JOHN M. MCHUGH, New York NEIL ABERCROMBIE, Hawaii TERRY EVERETT, Alabama MARTY MEEHAN, Massachusetts ROSCOE G. BARTLETT, Maryland SILVESTRE REYES, Texas HOWARD P. ‘‘BUCK’’ MCKEON, California VIC SNYDER, Arkansas MAC THORNBERRY, Texas ADAM SMITH, Washington WALTER B. JONES, North Carolina LORETTA SANCHEZ, California ROBIN HAYES, North Carolina MIKE MCINTYRE, North Carolina KEN CALVERT, California ELLEN O. TAUSCHER, California JO ANN DAVIS, Virginia ROBERT A. BRADY, Pennsylvania W. TODD AKIN, Missouri ROBERT ANDREWS, New Jersey J. RANDY FORBES, Virginia SUSAN A. DAVIS, California JEFF MILLER, Florida JAMES R. LANGEVIN, Rhode Island JOE WILSON, South Carolina RICK LARSEN, Washington FRANK A. LOBIONDO, New Jersey JIM COOPER, Tennessee TOM COLE, Oklahoma JIM MARSHALL, Georgia ROB BISHOP, Utah MADELEINE Z. -

El Caribe En La Post-Guerra Fria

Centro Latinoamericano de Defensa y Desarme (CLADDE) Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales (FLACSO) Area de Investigación Paz y Desarrollo en el Caribe Instituto de Estudios del Caribe Universidad de Puerto Rico Departamento de Estudios Portorriqueños y del Caribe Hispano y Centro de Análisis Histórico de Rutgers University (New Brunswick) EL CARIBE EN LA POST-GUERRA FRIA ESTUDIO ESTRATEGICO DE AMERICA LATINA 1992 1 1993 La publicación de este libro y la elaboración de las tendencias regionales, las estadísticas y algunos de los artículos aquí publicados, ha sido realizada gracias al apoyo de The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation para el proyecto "Transformaciones Globales y Paz", y de la Fundación Ford, para las actividades de investigación del Area de Relaciones Internacionales y Militares de FLACSO Chile. Las opiniones que en los artículos se presentan, así como Jos análisis e interpretaciones que en ellos se contienen, son de responsabilidad exclusiva de sus autores y no reflejan necesariamente los puntos de vista de las Instituciones a las cuales se encuentran vinculados. Producción editorial: M. Cristina de los Ríos FLACSO-Chile Casilla 3213, Correo Central, Santiago Fax: 274.1004 Teléfono: 225.7357- 225.6955 @ CLADDE - FLACSO Inscripción N° 69347 I.S.B.N. 956-211-022-1 Impreso en S.R. V. Impresos S.A. - Tocomal 2052 Teléfono: 556.5796- 551.9123 Enero de 1994 Impreso en Chile 1 Printed in Chile INDICE PREFACIO 7 INTRODUCCION 15 PRESENTACION 21 1 EL CARIBE EN LA POST-GUERRA FRIA LA POLITICA MILITAR DE LOS ESTADOS UNIDOS HACIA EL CARIBE EN LA DECADA DE LOS 90 Humberto García M. -

Union Calendar No. 615 110Th Congress, 2D Session – – – – – – – – – – – – House Report 110–942

1 Union Calendar No. 615 110th Congress, 2d Session – – – – – – – – – – – – House Report 110–942 REPORT OF THE ACTIVITIES OF THE COMMITTEE ON ARMED SERVICES FOR THE ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS JANUARY 3, 2009.—Committed to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 79–006 WASHINGTON : 2009 VerDate Nov 24 2008 05:10 Jan 15, 2009 Jkt 079006 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4012 Sfmt 4012 E:\HR\OC\HR942.XXX HR942 wwoods2 on PRODPC68 with REPORTS E:\Seals\Congress.#13 HOUSE COMMITTEE ON ARMED SERVICES ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS IKE SKELTON, Missouri, Chairman JOHN SPRATT, South Carolina DUNCAN HUNTER, California, Ranking SOLOMON P. ORTIZ, Texas Member GENE TAYLOR, Mississippi JIM SAXTON, New Jersey NEIL ABERCROMBIE, Hawaii JOHN M. MCHUGH, New York MARTY MEEHAN, Massachusetts 5 TERRY EVERETT, Alabama SILVESTRE REYES, Texas ROSCOE G. BARTLETT, Maryland VIC SNYDER, Arkansas HOWARD P. ‘‘BUCK’’ MCKEON, California ADAM SMITH, Washington MAC THORNBERRY, Texas LORETTA SANCHEZ, California WALTER B. JONES, North Carolina MIKE MCINTYRE, North Carolina ROBIN HAYES, North Carolina ELLEN O. TAUSCHER, California KEN CALVERT, California 4 ROBERT A. BRADY, Pennsylvania JO ANN DAVIS, Virginia 7 ROBERT ANDREWS, New Jersey W. TODD AKIN, Missouri SUSAN A. DAVIS, California J. RANDY FORBES, Virginia RICK LARSEN, Washington JEFF MILLER, Florida JIM COOPER, Tennessee JOE WILSON, South Carolina JIM MARSHALL, Georgia FRANK A. LOBIONDO, New Jersey MADELEINE Z. BORDALLO, Guam TOM COLE, Oklahoma MARK E. UDALL, Colorado ROB BISHOP, Utah DAN BOREN, Oklahoma MICHAEL TURNER, Ohio BRAD ELLSWORTH, Indiana JOHN KLINE, Minnesota NANCY BOYDA, Kansas CANDICE S. -

Call Sign Chaos: Learning to Lead by Jim Mattis and Bing West

Call Sign Chaos: Learning to Lead by Jim Mattis and Bing West • Featured on episode 440 • Purchasing this book? Support the show by using the Amazon link inside our book library. Dave’s Reading Highlights In late November 2016, I was enjoying Thanksgiving break in my hometown on the Columbia River in Washington State when I received an unexpected call from Vice President–elect Pence. Would I meet with President-elect Trump to discuss the job of Secretary of Defense of the United States? I had taken no part in the election campaign and had never met or spoken to Mr. Trump, so to say that I was surprised is an understatement. Further, I knew that, absent a congressional waiver, federal law prohibited a former military officer from serving as Secretary of Defense within seven years of departing military service. Given that no waiver had been authorized since General George Marshall was made secretary in 1950, and I’d been out for only three and a half years, I doubted I was a viable candidate. I figured that my strong support of NATO and my dismissal of the use of torture on prisoners would have the President-elect looking for another candidate. Standing beside him on the steps as photographers snapped away and shouted questions, I was surprised for the second time that week when he characterized me to the reporters as “the real deal.” Days later, I was formally nominated. That During the interview, Mr. Trump had asked me if I could do the job of Secretary of Defense.