St. Ninian's Isle Treasure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Castingmetal

CASTING METAL Sophistication from the surprisingly simple with a room casting. Hmmmm. I I asked Beth where in the world she BROOM pored through every new and learned how to cast metal using the Bvintage metals technique book Brad Smith offers a Broom business end of a broom. “It’s an old BY HELEN I. DRIGGS on my shelf and I couldn’t find a men- Casting Primer, page 32, hobbyist trick. I learned about it from a tion of the process anywhere. This and a project for using very talented guy named Stu Chalfant the elements you cast. transformed my curiosity into an who gave a demo for my rock group TRYBROOM-CAST IT YOURSELFE urgent and obsessive quest. I am an G — the Culver City [California] Rock & A TURQUOISE PENDANT P information junkie — especially Mineral Club. This was six or seven when it comes to studio jewelry — years ago, and I instantly fell in love and I love finding out new, old fash- with the organic, yet orderly shapes.” ioned ways of doing things. But, I am also efficient. So I A few years passed before Beth tried the technique her- knew the best way to proceed was to seek out Beth self. “The first of our club members to experiment with it Rosengard, who has transformed this delightfully low-tech was Brad 34Smith, who now includes the technique in the approach to molten metal into a sophisticated level of artis- classes he teaches at the Venice Adult School.” After admir- tic expression. I had made a mental note to investigate ing some early silver castings Brad had made, she begged broom casting when I saw her winning earrings in the 2006 him for a sample and later incorporated his work into her Jewelry Arts Awards. -

Repoussé Work for Amateurs

rf Bi oN? ^ ^ iTION av op OCT i 3 f943 2 MAY 8 1933 DEC 3 1938 MAY 6 id i 28 dec j o m? Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from Boston Public Library http://www.archive.org/details/repoussworkforamOOhasl GROUP OF LEAVES. Repousse Work for Amateurs. : REPOUSSE WORK FOR AMATEURS: BEING THE ART OF ORNAMENTING THIN METAL WITH RAISED FIGURES. tfjLd*- 6 By L. L. HASLOPE. ILLUSTRATED. LONDON L. UPCOTT GILL, 170, STRAND, W.C, 1887. PRINTED BY A. BRADLEY, 170, STRAND, LONDON. 3W PREFACE. " JjJjtfN these days, when of making books there is no end," ^*^ and every description of work, whether professional or amateur, has a literature of its own, it is strange that scarcely anything should have been written on the fascinating arts of Chasing and Repousse Work. It is true that a few articles have appeared in various periodicals on the subject, but with scarcely an exception they treated only of Working on Wood, and the directions given were generally crude and imperfect. This is the more surprising when we consider how fashionable Repousse Work has become of late years, both here and in America; indeed, in the latter country, "Do you pound brass ? " is said to be a very common question. I have written the following pages in the hope that they might, in some measure, supply a want, and prove of service to my brother amateurs. It has been hinted to me that some of my chapters are rather "advanced;" in other words, that I have gone farther than amateurs are likely to follow me. -

Rene Lalique Shaun Leane

In your written exam you will have to compare and contrast the work of two designers. Remember the following sentence it will help you remember the similarities and differences in the designer’s work that you should discuss. “St Paul’s Pupils’ Can Make Tasty Sausage Sandwiches On Toast!!!” Rene Lalique THE Shaun Leane b.1860 – 1945 DESIGNERS Began working in 1980’s to France present day – London, UK Lalique was an important figure in ‘This is my signature; something the “Art nouveau” movement. that’s refined, delicate, but This movement was inspired by powerful.’ natural, organic forms, like Organic forms are one of Leane’s flowers and plants; favourite inspirations. He Lalique’s work consisted of soft, describes nature as beautiful and flowing curved lines. fragile yet there are hidden He also liked to use female figures elements of strength and and faces in his work; danger. He like to create balance Feminine, detailed, realistic. in his pieces Many of Lalique’s design were Soft flowing lines paired with symmetrical. sharp points S for SHAPE Dragonfly woman corsage ornament, 1898. Gold, enamel, moonstones, and diamonds Tahitian pearl and pheasant claw earrings by for McQueen, 2001 Detailed, feminine, Art Nouveau P Statement jewellery, wearable art, Statement jewellery. for Detailed. Avant Garde (meaning PRODUCT experimental & innovative) Very detailed, fairly large, heavy Larger fashion pieces which were pieces so not very easy to wear. P commissioned by McQueen were for made from lightweight materials PRACTICALITY which made them easy to wear down the runway. Not for everyday wear, were designed to complement and add extra drama to fashion pieces. -

Soroptimist Brooch 100 Years Order Form

THE 100 YEARS BROOCH A unique piece of jewellery CELEBRATING OUR CENTENARY - A UNIQUE PIECE OF SOROPTIMIST JEWELLERY An opportunity to invest in a unique piece of jewellery to commemorate our Soroptimist centenary. Many Soroptimists have purchased and enjoyed specially designed pieces in the past and this will be a stunning piece to add to your collection. Formed in the Centennial colour of purple, the stone is set in a silver finish metal, with rows of crystals on either side. Our Soroptimist logo sits proudly in the middle of the piece, inscribed with our commemorative dates ‘1921-2021’ and ‘100 years’ The brooch is 37mm in diameter with a thickness of 2mm. It is an extremely versatile piece that may be worn as a brooch or pendant, bringing happy memories of Soroptimist friends and events all over the world. To place your order for this unique brooch, please complete the form below and send to: SIGBI Federation Office, 2nd Floor Beckwith House, Wellington Road North, Stockport, SK4 1AF Dispatch will begin end September 2020 Title . Surname . Initials . Club . Address . Post/Zip Code . Contact details: Tel: . E-mail: . Please tick appropriate boxes below. The cost of the Soroptimist 100 Brooch is £25.00 per item plus P&P. Please note: P&P is calculated on Postage & Packaging Costs the number of brooches ordered. Please complete the order form below along with your payment: UK Second Class - 1-10 Brooches - £4.00 UK Second Class Signed For - Quantity . Sub Total . plus P&P (see the P&P table for costs) Grand Total . -

Heat Exchange

HEAT EXCHANGE Curated by: Elizabeth Turrell & Beate Gegenwart Dedicated to: Pamela Rawnsley (1952 - 2014) When first approached by artists and curators Beate Gegenwart and Elizabeth Turrell to launch Heat Exchange 2 at The Makers Guild in Wales Gallery, Craft in the Bay, I was immediately captivated by the concept of artists brought together from various regions of the world to not only exhibit together but to share their normally private creative process via an artist blog. As an avid follower of heat-exchange.crimsoncactus.net over the past two years, my eyes have been opened to the rich depth of skill and knowledge these artists possess and their generous sharing of discovery, experiments, struggles and breakthroughs with this fascinating medium. This exhibition presents the beautiful and thought-provoking outcomes of this creative journey. Charlotte Kingston, Exhibitions Officer, The Makers Guild in Wales In this exhibition Elizabeth and Beate have attracted leading lights working in enamel from around the world. This will ensure that many more people will be as thrilled as I have been by the riot of colour, texture and design, which can be achieved by skilled and creative makers responding to the application of enamel. Heat Exchange 2 is eagerly awaited and will, I am certain, generate more conversation, celebration and appreciation of the work of contemporary makers in this field. Jean Wood, an enthusiast 2 MAKERS, MYTHS AND GODS In Greek myth, Hephaestus was the god of craftsmen: a maker of living things. Giving a maker place in the company of gods seems a hopeful symbol of a society that valued what the maker brings. -

The Garnet Carbuncle in Early Medieval Europe

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works School of Arts & Sciences Theses Hunter College Spring 5-15-2020 Sacred Blood and Burning Coal: The Garnet Carbuncle in Early Medieval Europe Sinead L. Murphy CUNY Hunter College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/hc_sas_etds/591 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Sacred Blood and Burning Coal: The Garnet Carbuncle in Early Medieval Europe by Sinead Murphy Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Art History, Hunter College The City University of New York Spring 2020 May 15th, 2020 Cynthia Hahn Date Thesis Sponsor May 15th, 2020 Maria Loh Date Second Reader i Table of Contents List of Illustrations ii Introduction: Garnets in the Merovingian Period…………………………………………………1 Chapter 1: Garnet in Classical and Early Medieval Texts……………………………………….11 I. Carbuncle and Anthrax in Classical and Early Medieval Lapidaries II. Carbuncle in Scripture and Christian Lapidaries III. Pagan Influence on the Christian Symbolism of Garnets Chapter 2: Garnets in Everyday Life…………………………………………………………….34 I. Garnet Jewelry in Frankish Costume II. Garnet Ecclesiastical Objects Chapter 3: The Role of Garnets in Christian Funerary Ritual…………………………………...49 I. Prayers for the Dead II. Grave Goods and Dressed Burials III. Metaphorical Representations of Carbuncle Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………….59 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………………..60 Illustrations………………………………………………………………………………………64 i List of Illustrations Fig. 1: Pair of quatrefoil mounts, Early Byzantine, 2nd half of 5th century. -

Tiara Pair of Earrings in Chinoiserie Style

1 1. Italy or France Tiara Gold and coral, about 1817 Purchased with funds given by Rita Barbour Kern, 1996.27 French Neoclassicism revived the fashion for wearing a tiara, a head ornament based on an ancient Greek diadem. Tiaras of varying degrees of intrinsic value were worn by every woman from the middle classes to royalty. Coral, which was believed to posses protective powers, was often used in jewelry for children and young adults. A portrait painted by Luigi Bernero in 1817 of Maria Teresa of Savoy (1803– 1879) shows the 14-year-old Italian princess wearing a hair ornament almost exactly like this tiara. Most coral in Europe came from the sea around Naples and nearby Torre del Greco. In the 19th century coral jewelry became a fashionable souvenir. This was partly because people could travel more once the Napoleonic wars had ended in 1815, but also due to the growing popularity of Luigi Bernero (Italy, 1775–1848), Maria Teresa di Savoia. Oil on canvas, naturalistic jewelry in the 1850s. about 1817. Palazzo Reale, Turin, Italy 2. and pagoda-shaped elements of these earrings reflect the England period’s romantic taste for the Far East, known as chinoiserie Pair of Earrings in (sheen-WAH-zer-ee). Chinoiserie Style Pierced earrings were a sign of maturity. The first pair of earrings was usually given to a young girl in England at Silver, gold, diamonds, pearls and rubies, age 16, when simple ‘top-and-drop’ pearl earrings were considered to be more appropriate for a young, unmarried about 1820 girl. -

Artist Jewellery Is Enjoying a Renaissance. Aimee Farrell Looks At

Artist jewellery Right: Catherine Deneuve wearing Man Ray’s Pendantif-Pendant earrings in a photo by the artist, 1968. Below: Georges Braque’s Circé, 1962 brooch Photo: Sotheby’s France/ArtDigital Studio © Man Ray Trust/ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2017; Braque jewellery courtesy Diane Venet; all other jewellery shown here © Louisa Guinness Gallery Frame the face Artist jewellery is enjoying a renaissance. Aimee Farrell looks at its most captivating – and collectible – creations, from May Ray’s mega earrings to Georges Braque’s brooches 16 Fashion has long been in thrall of artist jewellery. In the 1930s, couturier Elsa Schiaparelli commissioned her circle of artist friends including Jean Cocteau and Alberto Giacometti to create experimental jewels for her collections; art world fashion plate Peggy Guggenheim boasted of being the only woman to Clockwise from left: wear the “enormous mobile earrings” conceived Man Ray’s La Jolie, 1970 pendant with lapis; The by kinetic artist Alexander Calder; and Yves Saint Oculist, 1971 brooch Laurent, a generous patron of the French husband- in gold and malachite; and his photograph of and-wife artist duo “Les Lalannes” summoned Claude Nancy Cunard, 1926 © Man Ray Trust/ADAGP, Lalanne to conjure a series of bronze breast plates, Paris and DACS, London akin to armour, for his dramatic autumn/winter 2017; Telimage, 2017 1969 show. So when Maria Grazia Chiuri enlisted Lalanne, now in her nineties, to devise the sculptural copper Man Ray jewels for her botanical-themed Christian Dior A brooch portraying Lee Miller’s lips, rings complete with tiny Couture debut this year, she put artist jewellery firmly tunnels that offer an alternative perspective on the world and 24 carat gold sunglasses – it’s no surprise that the avant-garde back on the agenda. -

Maker-Muse-Addendum-A.Pdf

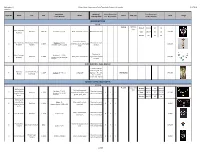

Addendum A Maker Muse: Women and Early Twentieth Century Art Jewelry 5/1/2018 Checklist Dimensions Mounting/ Mount Dimensions Case Dimensions Object No. Maker Title Date Media Case # Case Type Value Image H x W x D inches Installing Notes H x W x D inches H x W x D inches INTRODUCTION FC 1/6 FlatTable FC 1/6 Overall 50 1/4 36 20 Case Mrs. Charlotte 1 Pendant 1884-90 2 3/8 x 1 1/2 x 1/4 Gold, amethyst, enamel Mounted into deck - - - Case 38 1/4 36 20 $10,000 Newman Vitrine 12 36 12 Carved moonstone, Mrs. Charlotte Mary Queen of Scots Necklace: 20 1/2 Mounted on riser 2 c. 1890 amethyst, pearl, yellow gold - - - $16,500 Newman Pendant Pendant: 2 3/4 x 1 1/16 on deck chain Displayed in Mrs. Charlotte Necklace: L: 15 3/8 3 Necklace c. 1890 Gold, pearl, aquamarine original box directly - - - $19,000 Newman Pendant: 2 5/8 x 3 15/16 on deck INTRODUCTION - WALL DISPLAY Framed, D-Rings; wall hang; 68 - 72 Alphonse Sarah Bernhardt as 4 c. 1894 Framed: 96 x 41 x 2 Lithograph degrees F, 45 - 55% - - - Wall display $40,000 Mucha Gismonda RH, 5 - 7 foot candles (50 - 70 lux) BRITISH ARTS AND CRAFTS TC 1/10 TC 1/10 Large table Attributed to Overall 83 3/4 42 26 1/2 Gold, white enamel, case Jessie Marion Necklace: 5 11/16 Mounted on oval 5 Necklace c. 1905 chrysoberyl, peridot, green 8 6 1 Table 38 1/4 42 26 1/2 $11,000 King for Liberty Pendant: 2 x 13/16 riser on back deck garnet, pearl, opal & Co. -

Ballou-Dama Earring & Brooch Catalog

Earring & Brooch Components W.R. Cobb Wants You To Be Satisfied Ballou-Dama, the newest addition to the W.R. Cobb Company family, embraces a philosophy to provide the same service to all our customers in their time zone, in their language, for their specific market needs. International customer service representatives are located all over the world. Ballou-Dama is located in East Providence RI and has translators in several languages to accommodate our customers, both in the United States and overseas. US/China Latin America (Portugese & Spanish) Contact: Eve Jiang Contact: Cidalia Mello Ballou/Dama Ballou/Dama 800 Waterman Avenue 800 Waterman Avenue East Providence, RI 02914 East Providence, RI 02914 Phone: 800-428-0040 Phone: 800-428-0040 Fax: 800-428-0041 Fax: 800-428-0041 Email: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] China/Qing Dao Thailand Contact: Sining Li Contact: Maneerat Chaiowarees E-mail Sales: [email protected] Phone: 66-2-703-3134 QQ: 2078070049 Fax: 66-2-703-3135 Mobile: 86-131-6210-7340 E-mail Sales: [email protected] We Chat: 86-131-6210-7340 Proud of our ISO 9001: 2015 and 14001: 2015 Certifications Ballou-Dama www.wrcobb.com | E: [email protected] | 800-428-0040 Page 1 of 18 v1 EAR WIRES GANCHOS PARA ARETES EN LATON Y ACERO INOXIDABLE Lead Free *Use these ear wires with our quality fishhook stoppers found on page 2 of Packaging Components EW-WFH44B* EW-WF30B* EW-WFH05B* EW-WFH13B Length 30mm 2.5MM Ball: Length: .719” Outward Loop 2,000 pcs/bag Dapped (18.26mm) Length: .754” (19.1mm) Length 30mm -

Please Download PDF of Portfolio Here

HANNAH OATMAN Artist Portfolio Please see page 11 for captions 11 22 34 49 510 611 715 820 919 1017 HANNAH OATMAN [email protected] Portfolio Image List 1. Title: Collect Me! 01: Dreamboat 7. Title: Out of Touch (“unboxing”, pre-assembly) Materials: Powder-coated brass, polyurethane Materials: Brooch: Laser cut acrylic, cast brass. foam Box: Paper, cardboard (created in InDesign, Date: 2018 printed, cut, and hand assembled). Dimensions: 2.5 x 3.5 x 0.5 ” Date: 2019 Dimensions: Brooch 3.5 x 3 x 0.5, 8. Title: Collage 04 (brooch) Box 4 x 6 x 2 ” Materials: Steel, sterling silver, vitreous enamel, 18K gold 2. Title: Collect Me! 09: Unicorn Date: 2017 Materials: Laser cut acrylic, 18K gold-plated Dimensions: 4 x 6 x .075” sterling silver. Date: 2019 Dimensions: 3.5 x 3 x 0.5 ” 9. Title: Stack 03 (brooch) Materials: Sterling silver, steel, vitreous 3. Title: Collect Me! 01: Dreamboat enamel, 18K gold Materials: Brooch: Laser cut acrylic, cast brass. Date: 2018 Box: Paper, cardboard. Dimensions: 2.75 x 2.75 x 0.5 ” Date: 2019 Dimensions: Brooch 3.5 x 3 x 0.5 ” 10. Title: Collage 05 (necklace) Materials: Steel, copper, sterling silver, vitreous 4. Title: Art Over Time brooch bases with charms enamel, 18K gold from month 1, 2, 3, and 4 of subscription Date: 2017 Materials: acrylic, cast sterling silver, plastic Dimensions: 13.5 x 8.5 x 0.75 ” mini side-release buckles, nylon ribbon, wood. Date: 2020 Dimensions: Brooch base: 3.75 x 1.75 x 0.75 ” With charms attached: 3.75 x 3.75 x 0.75 ” 5. -

The Art of Creating Enamel Jewelry

The Art of Creating Enamel Jewelry In the tradition of Lalique, Fabergé and Louis Tiffany, the Nicole Barr Collection continues the art of fine enameling into the 21st century. With a history dating back at least 3,000 years, enameling is still valued today for the color and life that is brought to every hand-enameled piece of jewelry. Nicole Barr designs showcase the art of enameling on 18 K gold and sterling silver – complemented by diamonds, gemstones and pearls. What is “Hard-Fired Enameling?” Enameling is the art of fusing powdered glass to metals such as gold or silver. The enamel color comes from specific blends of rare metals like gold, cobalt and manganese. The fusion between enamel and metal takes place in a kiln with temperatures up to 850° C – with different colors requiring different temperatures – and therefore often multiple firings for the same piece. This is what is meant by “hard-fired enamel”- also called vitreous enamel. For your customer, it means owning a piece of jewelry with a lustrous color that will never change. The Metals and Glass Used in Enameling The most popular metals used in enameling are sterling silver and high-karat gold such as 18 K. A high-carat metal is required because vitreous enamel will react to the higher amount of alloys in lower quality metals and therefore will not fire properly. The artist can choose from opaque or transparent enamel colors. Opaque - After firing, the enamel is dense and does not permit the metal to be reflected. Opaque enamels are excellent for creating contrast and when used with transparent enamels add depth and dimension to a piece.