The Cross Border Financial Impact of Violent Events

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Much Globalization Is There in the World Stock Markets and Where Is It?

How much Globalization is there in the World Stock Markets and where is it? Gianni Nicolini University of Rome “Tor Vergata” Faculty of Economics Researcher in Banking and Finance [email protected] Ekaterina Dorodnyk University of Rome “Tor Vergata” Faculty of Economics PhD in Banking and Finance – PhD Candidate [email protected] ABSTRACT Globalization, as the process of integration of national economies into the international economy through trade, foreign direct investment, capital flows, migration and the spread of technology, has been analyzed by academic literature in different manners. Anyway a comprehensive analysis in a worldwide perspective that compares all the main stock markets' performances in a long term period misses. In this paper, the authors try to fill this gap by a correlation analysis applied to stock exchange market indexes. This methodology is implemented in order to highlight the dynamic trend of financial market globalization. The paper investigates the degree of association of weekly returns for 53 international stock exchanges from 1995 to 2010 in a year-by-year approach, trying to evaluate how the average correlation through national stock indexes changed by the time. Moreover, an analysis of single geographical areas (North America and Canada, Latin America, Asia and Oceania, Northern Europe, Eastern Europe and Western Europe) has been done in order to test the hypothesis that globalization follows a homogenous (or heterogeneous) path. Results suggest an upward globalization trend that is developing at an increasing growth rate. Furthermore, an analysis of single geographical areas supports the hypothesis that globalization is a heterogeneous phenomena where different cluster of countries are engaged in different manners. -

RGB Perspectives July 12, 2021 Written by Rob Bernstein ([email protected]) RGB Capital Group LLC • 858-367-5200 •

RGB Perspectives July 12, 2021 Written by Rob Bernstein ([email protected]) RGB Capital Group LLC • 858-367-5200 • www.rgbcapitalgroup.com Not much has changed in the market over the last week with a divided stock market environment. The S&P 500 Index continues to trend up and closed at an all-time high on Friday. Many of the other major stock market indices, including the S&P 500 Index Dow Jones, Nasdaq Composite Index and the Nasdaq 100 have Six-Month Chart similar chart patterns and closed at all-time highs at the end of last week. Other segments of the market are stuck in intermediate-term trading ranges. These include the Russell 2000 Index, S&P 400 Index, NYSE Composite Index, and the Value Line Arithmetic Index. The Russell 2000 Index is at the same level it was at back in February. Russell 200 Index Six-Month Chart BAML High-Yield Master II Index Six-Month Chart In this type of environment where stocks are giving mixed signals, I use junk bonds to provide additional clues to the overall direction of the market as they are generally a good barometer of the overall health of the market. The BAML 50-Day Moving Average High-Yield Master II Index continues to trend up above its 50- day moving average on low volatility. While risk management is always important, it is more important in less certain market environments such as the stock market environment we are experiencing now. I continue to focus on risk management to different degrees in the RGB Capital Group investment strategies. -

A Primer on U.S. Stock Price Indices

A Primer on U.S. Stock Price Indices he measurement of the “average” price of common stocks is a matter of widespread interest. Investors want to know how “the Tmarket” is doing, and to be able to compare their returns with a meaningful benchmark. Money managers often have their compensation tied to performance, typically measured by comparing their results to a benchmark portfolio, so they and their clients are interested in the benchmark portfolio’s returns. And policymakers want to judge the potential for sudden adjustments in stock prices when differences from “fundamental value” emerge. The most widely quoted stock price index, the Dow Jones Industrial Average, has been supplemented by other popular indices that are constructed in a different way and pose fewer problems as a measure of stock prices. At present, a number of stock price indices are reported by the few companies that we will consider in this paper. Each of these indices is intended to be a benchmark portfolio for a different segment of the universe of common stocks. This paper discusses some of the issues in constructing and interpreting stock price indices. It focuses on the most widely used indices: the Dow Jones Industrial Average, the Stan- dard & Poor’s 500, the Russell 2000, the NASDAQ Composite, and the Wilshire 5000. The first section of this study addresses issues of construction and interpretation of stock price indices. The second section compares the movements of the five indices in the last two decades and investigates the Peter Fortune relationship between the returns on the reported indices and the return on “the market.” Our results suggest that the Dow Jones Industrial Average (Dow 30) The author is a Senior Economist and has inherent problems in its construction. -

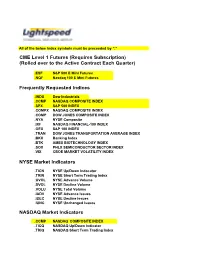

CME Level 1 Futures (Requires Subscription) (Rolled Over to the Active Contract Each Quarter)

All of the below Index symbols must be preceeded by "." CME Level 1 Futures (Requires Subscription) (Rolled over to the Active Contract Each Quarter) .ESF S&P 500 E Mini Futures .NQF Nasdaq 100 E Mini Futures Frequently Requested Indices .INDU Dow Industrials .CCMP NASDAQ COMPOSITE INDEX .SPX S&P 500 INDEX .COMPX NASDAQ COMPOSITE INDEX .COMP DOW JONES COMPOSITE INDEX .NYA NYSE Composite .IXF NASDAQ FINANCIAL-100 INDEX .OEX S&P 100 INDEX .TRAN DOW JONES TRANSPORTATION AVERAGE INDEX .BKX Banking Index .BTK AMEX BIOTECHNOLOGY INDEX .SOX PHLX SEMICONDUCTOR SECTOR INDEX .VIX CBOE MARKET VOLATILITY INDEX NYSE Market Indicators .TICN NYSE Up/Down Indocator .TRIN NYSE Short Term Trading Index .UVOL NYSE Advance Volume .DVOL NYSE Decline Volume .VOLU NYSE Total Volume .IADV NYSE Advance Issues .IDEC NYSE Decline Issues .IUNC NYSE Unchanged Issues NASDAQ Market Indicators .CCMP NASDAQ COMPOSITE INDEX .TICQ NASDAQ Up/Down Indicator .TRIQ NASDAQ Short Term Trading Index .UVOQ NASDAQ Advance Volume .DVOLQ NASDAQ Decline Volume .VOLQ NASDAQ Total Volume AMEX Market Indicators .UVOA AMEX Adavance Volume .DVOA AMEX Decline Volume .VOLA AMEX Total Volume .IADVA AMEX Advance Issues .IDECA AMEX Decline Issues .ISAAU AMEX Unchanged Issues Philadelphia Indices .SOX PHLX SEMICONDUCTOR SECTOR INDEX .XAU PHLX Gold/Silver SectorSM .HGX PHLX Housing SectorSM .OSX PHLX Oil Service SectorSM .UTY PHLX Utility SectorSM .EPX SIG Oil Exploration and Production IndexSM .BKX Banking Index .BTK Biotechnology Index . -

Security Market Manipulations and the Assurance of Market Integrity

Security Market Manipulations and the Assurance of Market Integrity By Shan Ji Supervisor: Professor Mike Aitken Co-supervisor: Professor Frederick H. deB. Harris This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Finance At The University of New South Wales Banking and Finance Australian School of Business 2009 Abstract This dissertation is motivated by two major factors. First, there have been no direct studies conducted for the relationship between market integrity and market efficiency and the driving forces behind the cross-sectional variations in market quality. Second, a better understanding the relationships among market integrity, market efficiency and other mechanism design factors for securities exchanges will facilitate securities exchanges achieve a satisfactory level of market quality. This dissertation consists of three chapters. In Chapter 1, a review of literature on market manipulation will be given. A series of common securities market manipulation strategies and corresponding market surveillance alerts will be explained and defined. In Chapter 2, we develop a testable hypothesis that market manipulation as proxied by the incidence of ramping alerts would raise transaction cost for completing larger trades. We find ramping alert incidence positively related to effective spreads in 8 of 10 turnover deciles from most liquid to thinnest-trading securities. The magnitude of the increase in effective spreads when ramping manipulation incidence doubles is economically significant, 30 to 40 basis points in many -

Thomson One Symbols

THOMSON ONE SYMBOLS QUICK REFERENCE CARD QUOTES FOR LISTED SECURITIES TO GET A QUOTE FOR TYPE EXAMPLE Specific Exchange Hyphen followed by exchange qualifier after the symbol IBM-N (N=NYSE) Warrant ' after the symbol IBM' When Issued 'RA after the symbol IBM'RA Class 'letter representing class IBM'A Preferred .letter representing class IBM.B Currency Rates symbol=-FX GBP=-FX QUOTES FOR ETF TO GET A QUOTE FOR TYPE Net Asset Value .NV after the ticker Indicative Value .IV after the ticker Estimated Cash Amount Per Creation Unit .EU after the ticker Shares Outstanding Value .SO after the ticker Total Cash Amount Per Creation Unit .TC after the ticker To get Net Asset Value for CEF, type XsymbolX. QRG-383 Date of issue: 15 December 2015 © 2015 Thomson Reuters. All rights reserved. Thomson Reuters disclaims any and all liability arising from the use of this document and does not guarantee that any information contained herein is accurate or complete. This document contains information proprietary to Thomson Reuters and may not be reproduced, transmitted, or distributed in whole or part without the express written permission of Thomson Reuters. THOMSON ONE SYMBOLS Quick Reference Card MAJOR INDEXES US INDEXES THE AMERICAS INDEX SYMBOL Dow Jones Industrial Average .DJIA Airline Index XAL Dow Jones Composite .COMP AMEX Computer Tech. Index XCI MSCI ACWI 892400STRD-MS AMEX Institutional Index XII MSCI World 990100STRD-MS AMEX Internet Index IIX MSCI EAFE 990300STRD-MS AMEX Oil Index XOI MSCI Emerging Markets 891800STRD-MS AMEX Pharmaceutical Index -

Dual-Class Shares: the Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

DUAL-CLASS SHARES: THE GOOD, THE BAD, AND THE UGLY A Review of the Debate Surrounding Dual-Class Shares and Their Emergence in Asia Pacific DUAL-CLASS SHARES: THE GOOD, THE BAD, AND THE UGLY A Review of the Debate Surrounding Dual-Class Shares and Their Emergence in Asia Pacific ©2018 CFA Institute CFA Institute is the global association of investment professionals that sets the standards for professional excellence. We are a champion for ethical behavior in investment markets and a respected source of knowledge in the global financial community. Our mission is to lead the investment profession globally by promoting the highest standards of ethics, education, and professional excellence for the ultimate benefit of society. ISBN: 978-1-942713-58-6 August 2018 Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank the interviewees who have offered their expert knowledge and unique perspectives of the subject. We appreciated their time to explain the rationale behind their considerations to support or oppose to the introduction of dual-class share structures in their respective markets, which allowed us to cover the topic with real-life narrative: - Ken Bertsch, Executive Director, and Amy Borrus, Deputy Director, Council of Institutional Investors - Joseph Chan, CFA, Under Secretary for Financial Services and the Treasury, the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government - Yasuyuki Konuma, Executive Managing Director, Tokyo Stock Exchange - Gerard Lee How Cheng, CFA, Chief Executive Officer, Lion Global Investors Ltd. - Maggie Lee, Audit Partner and Head of Capital Markets Development Group in Hong Kong, KPMG - Yoo-Kyung Park, Director of Global Responsible Investment and Governance for the Asia Pacific region, APG Group N.V. -

Market Coverage Spans All North American Exchanges As Well As Major International Exchanges, and We Are Continually Adding to Our Coverage

QuoteMedia Data Coverage 1 03 Equities 04 International Equities 05 Options 05 Futures and Commodities 06-07 Market Indices 08 Mutual Funds, ETFs and UITs 09 FOREX / Currencies 10 Rates Data 11 Historical Data 12 Charting Analytics 13 News Sources 14 News Categories 15 Filings 16-17 Company Financials Data 18 Analyst Coverage and Earnings Estimates 18 Insider Data 19 Corporate Actions and Earnings 19 Market Movers 20 Company Profile, Share Information and Key Ratios 21 Initial Public Offerings (IPOs) 22 Contact Information 2 Equities QuoteMedia’s market coverage spans all North American exchanges as well as major international exchanges, and we are continually adding to our coverage. The following is a short list of available exchanges. North American New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) Canadian Consolidated Quotes (CCQ) • Level 1 • TSX Consolidated Level 1 • TSXV Consolidated Level 1 NYSE American (AMEX) Toronto Stock Exchange (TSX) Level 1 • Level 1 • Market by Price • Market By Order Nasdaq • Market By Broker • Level 1 • Level 2 Canadian Venture Exchange (TSXV) • Total View with Open View • Level 1 • Market by Price Nasdaq Basic+ • Market By Order • Level 1 • Market By Broker OTC Bulletin Board (OTCBB) Canadian Securities Exchange (CNSX) • Level 1 • Level 1 • Level 2 • Level 2 OTC Markets (Pinks) Canadian Alternative Trading Systems • Level 1 • Alpha Level 1 and Level 2 • Level 2 • CSE PURE Level 1 and Level 2 Cboe One • Nasdaq Canada Level 1 and Level 2 • Nasdaq CX2 Level 1 and Level 2 Cboe EDGX • Omega Canada Level 1 and Level 2 • LYNX Level 1 and Level 2 London Stock Exchange (LSE) • NEO and LIT • Level 1 • Instinet Canada (dark pool) • Level 2 • LiquidNet Canada (dark pool) • TriAct MatchNow (dark pool) 3 Equities Cont. -

Market Efficiency in KOSDAQ: a Volatility Comparison Between Main Boards and New Markets Using a Permanent and Transitory Component Model*

Asia-Pacific Journal of Financial Studies (2007) v36 n4 pp533-566 Market Efficiency in KOSDAQ: A Volatility Comparison between Main Boards and New Markets Using a Permanent and Transitory Component Model* Jong-Ho Park Sunchon National University, Jeonnam, Korea Sang-Koo Nam Korea University, Seoul, Korea Kyong Shik Eom** Korea Securities Research Institute, Seoul, Korea Received 15 September 2006; Accepted 01 June 2007 Abstract1) In this paper, we examine the market efficiency in KOSDAQ in the context of the relative market-macrostructure of main board and new market, focusing on volatility which is a market-microstructure variable. For this, we apply the Engle and Lee (1999) component model to the indices representing the main boards and new markets of Korea along with the U.S. and the U.K. stock markets, where the component model decomposes volatility into a permanent and a transitory component. In order to compare the estimates of each volatility component in main board and new market of a country, we develop new test statistics. We use the following indices for analyses: the KOSPI200 stock index and the KOSDAQ50 stock index, the S&P 500 index and the Nasdaq 100 index, the FTSE 100 index and the FTSE AIM all-shares index. We use intraday data exclusively for the KOSPI200 stock index (Jan. 2000 to Dec. 2005) and the KOSDAQ50 stock index (Nov. 2000 to Dec. 2005). We also use daily data for all related indices from Jan. 1990 to Dec. 2005, except for the KOSDAQ50 stock index (Jan. 2000 to Dec. 2005) and the FTSE AIM all-shares index (Jan. -

The Determinants of Terrorist Shocks' Cross-Market Transmission

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Drakos, Konstantinos Working Paper The Determinants of Terrorist Shocks' Cross-Market Transmission Economics of Security Working Paper, No. 17 Provided in Cooperation with: German Institute for Economic Research (DIW Berlin) Suggested Citation: Drakos, Konstantinos (2009) : The Determinants of Terrorist Shocks' Cross- Market Transmission, Economics of Security Working Paper, No. 17, Deutsches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung (DIW), Berlin This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/119344 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Economics of Security Working Paper Series Konstantinos Drakos The Determinants of Terrorist Shocks’ Cross-Market Transmission September 2009 Economics of Security Working Paper 17 Economics of Security is an initiative managed by DIW Berlin Economics of Security Working Paper Series Correct citation: Drakos, K. -

Baffled by Benchmarks?

BUILDING BLOCKS FOR RETIREMENT Investment Strategy Baffled By Benchmarks? You want to know how well your retirement plan investments are performing, but how can you tell? Looking at an investment’s total return is a start. But you should also compare your investment’s performance to a benchmark index to get a better idea of how well it’s doing. Different market indexes track different types of investments, so be sure you use an appropriate index as a yardstick. Here are some of the most common market indexes. Dow Jones Industrial AverageSM measures the performance of 30 of the largest U.S. corporations. The Dow is one of the most widely recognized indicators of stock market activity. Stocks listed on the Dow are often referred to as “blue chip” stocks. Standard & Poor’s 500 Index (S&P 500®) tracks the performance of 500 financial, industrial, transportation, and utility company large-cap stocks. The S&P 500 is a value-weighted index, which means it gives greater weight to stocks having the greatest market value. S&P MidCap 400 Index® tracks the performance of stocks from 400 medium-sized U.S. companies. Russell 2000® Index tracks the performance of approximately 2,000 small U.S. companies. It’s a benchmark for small-cap stocks. NASDAQ® Composite Index is a market-weighted index that follows domestic and international stocks traded through the NASDAQ electronic exchange. NYSE Composite Index® measures common stocks listed on the New York Stock Exchange. Wilshire 5000 Total Market Index® is the broadest index for the U.S. equity market. -

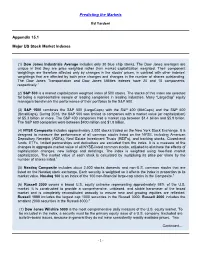

Appendix 15.1 Major US Stock Market Indexes

Predicting the Markets Ed Yardeni Appendix 15.1 Major US Stock Market Indexes (1) Dow Jones Industrials Average includes only 30 blue chip stocks. The Dow Jones averages are unique in that they are price weighted rather than market capitalization weighted. Their component weightings are therefore affected only by changes in the stocks’ prices, in contrast with other indexes’ weightings that are affected by both price changes and changes in the number of shares outstanding. The Dow Jones Transportation and Dow Jones Utilities indexes have 20 and 15 components, respectively.1 (2) S&P 500 is a market capitalization weighted index of 500 stocks. The stocks of this index are selected for being a representative sample of leading companies in leading industries. Many “LargeCap” equity managers benchmark the performance of their portfolios to the S&P 500. (3) S&P 1500 combines the S&P 500 (LargeCaps) with the S&P 400 (MidCaps) and the S&P 600 (SmallCaps). During 2016, the S&P 500 was limited to companies with a market value (or capitalization) of $5.3 billion or more. The S&P 400 companies had a market cap between $1.4 billion and $5.9 billion. The S&P 600 companies were between $400 million and $1.8 billion. (4) NYSE Composite includes approximately 2,000 stocks traded on the New York Stock Exchange. It is designed to measure the performance of all common stocks listed on the NYSE, including American Depository Receipts (ADRs), Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs), and tracking stocks. Closed-end funds, ETFs, limited partnerships and derivatives are excluded from the index.