We Build a Community

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Certificate of Insurance No.: CSA-2020-8-CCC Dated: July 23, 2020 This Document Supersedes Any Certificate Previously Issued Under This Number

Certificate of Insurance No.: CSA-2020-8-CCC Dated: July 23, 2020 This document supersedes any certificate previously issued under this number This is to certify that the Policy(ies) of insurance listed below ("Policy" or "Policies") have been issued to the Named Insured identified below for the policy period(s) indicated. This certificate is issued as a matter of information only and confers no rights upon the Certificate Holder named below other than those provided by the Policy(ies). Notwithstanding any requirement, term, or condition of any contract or any other document with respect to which this certificate may be issued or may pertain, the insurance afforded by the Policy(ies) is subject to all the terms, conditions, and exclusions of such Policy(ies). This certificate does not amend, extend, or alter the coverage afforded by the Policy(ies). Limits shown are intended to address contractual obligations of the Named Insured. Limits may have been reduced since Policy effective date(s) as a result of a claim or claims. Certificate Holder: Named Insured and Address: As per Schedule, AB Canadian Snowsports Association, including sanctioned activities for Cross Country Ski de fond Canada Suite 202 - 1451 West Broadway Vancouver, BC V6H 1H6 Which Includes sanctioned activities for the following: Alpine Canada Alpin, Canadian Adaptive Snowsports, Canadian Freestyle Ski Association, Canadian Snowboard Federation, Nordic Combined Canada Combiné Nordique, Ski Jumping Canada, Canadian Speed Skiing Association, Telemark Ski Canada Télémark, Canadian Ski Coaches Federation and Cross Country Ski de fond Canada This certificate is issued regarding: Event: 2019-2020 Season Date: July 14, 2020 - June 30, 2021 Location: Various, in Alberta Approved by: Cross Country Cross Ski de fond for Country Alberta The following addendum includes a list of additional Certificate Holders and Additional Insureds included to this certificate. -

Antler Lake State of the Watershed Report

Antler Lake State of the Watershed Report October 2019 i Antler Lake State of the Watershed Report North Saskatchewan Watershed Alliance 202 –9440 49th Street NW Edmonton, AB T6B 2M9 (587) 525‐6820 Email: [email protected] http://www.nswa.ab.ca The NSWA gratefully acknowledges operational funding support received from the Government of Alberta and many municipal partners. The North Saskatchewan Watershed Alliance (NSWA) is a non‐profit society whose purpose is to protect and improve water quality and ecosystem functioning in the North Saskatchewan River watershed in Alberta. The organization is guided by a Board of Directors composed of member organizations from within the watershed. It is the designated Watershed Planning and Advisory Council (WPAC) for the North Saskatchewan River under the Government of Alberta’s Water for Life Strategy. This report was prepared by Michelle Gordy, Ph.D., David Trew, B.Sc., Denika Piggott B.Sc., Breda Muldoon, M.Sc., and J. Leah Kongsrude, M.Sc. of the North Saskatchewan Watershed Alliance. Cover photo credit: Kate Caldwell Suggested Citation: North Saskatchewan Watershed Alliance (NSWA), 2019. Antler Lake State of the Watershed Report. Prepared for the Antler Lake Stewardship Committee (ALSC) Antler Lake State of the Watershed Report Executive Summary The Antler Lake Stewardship Committee (ALSC) formed in 2015 to address issues related to lake health. Residents at the lake expressed concerns about deteriorating water quality, blue‐green algal (cyanobacteria1) blooms, proliferation of aquatic vegetation, and low lake levels. In 2016, the Antler Lake Stewardship Committee approached the North Saskatchewan Watershed Alliance (NSWA) to prepare a State of the Watershed report. -

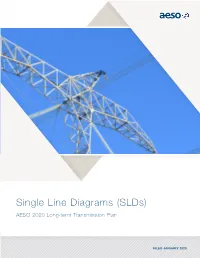

2020 Single Line Diagrams (Slds)

Single Line Diagrams (SLDs) AESO 2020 Long-term Transmission Plan FILED JANUARY 2020 Contents NEAR TERM REGIONAL TRANSMISSION PLANS 3 Northwest Planning Region 4 Northeast Planning Region 5 Edmonton Planning Region 6 Central Planning Region 7 South Planning Region 8 Calgary Planning Region 9 LONGER TERM ALBERTA-WIDE TRANSMISSION PLANS BY SCENARIO 10 Reference Case 11 High Cogeneration Sensitivity 12 Alternate Renewables Policy 13 High Load Growth 14 Table of Contents AESO 2020 Long-term Transmission Plan Single Line Diagrams (SLDs) NEAR TERM REGIONAL TRANSMISSION PLANS Northwest Planning Region Northeast Planning Region Edmonton Planning Region Central Planning Region South Planning Region Calgary Planning Region Rainbow #5 Rainbow Lake (RB5) #1 (RL1) RAINBOW ZAMA HIGH LEVEL 9 SULPHURPOINT 2 17 - Rainbow Lake COGEN 850S 795S 7L 786S 7L76 L 7 828S 7 2 7L 122 BASSETT 7L133 BLUMENORT RAINBOW 3 747S CHINCHAGA L9 832S LAKE 791S 7 7L64 RIVER 779S 7L1 9 MELITO 09 5 ) 7L o d 7LA59 890S t ARCENIEL ( o S 1 o 0 8 930S 7 6 w L 5 9 h 7 L Wescup 3 KEG RIVER c k 9 r 1 HAIG i e 1 B e 789S r 7 L RIVER 8 2 C 5 FORT NELSON 7 5 6 3 748S L L KEMP RIVER L FNG 7 7 1 RING CREEK 797S 1L359 18 - High Level 853S 7L120 MEIKLE 25 - Fort to ( d 4 o 7L138 905S 4 o ) McMurray L S 2 kw 1 1 ic 5 7L82 7L63 h 9 Fort Nelson T s Harvest ill (FNG1) CADOTTE H PetroCan Energy FNC RIVER 783S 6 1 KLC 0 3 1 1 HAMBURG L L LIVOCK LIVOCK British Columbia HOTCHKISS 7 7 NORCEN 855S West Cadotte KIDNEY LAKE 939S 500 kV 788S 1 Daishowa (WCD1) 812S 878S 5 SEAL L (DAI1) 7 BUCHANAN LAKE 869S -

Josephburg Terminal

JOSEPHBURG TERMINAL Headquartered in Calgary with operations in Western Canada and Hull, Texas, KEYERA operates an integrated Canadian-based midstream business with extensive interconnected assets and depth of expertise in delivering midstream energy solutions. Our business consists of natural gas gathering and processing, natural gas liquids (NGLs), fractionation, transportation, storage and marketing, iso-octane production and sales and diluent logistic services for oil sands producers. We are committed to conducting our business in a way that balances diverse stakeholder expectations and emphasizes the health and safety of our employees and the communities where we operate. Josephburg Terminal The Josephburg terminal is located near Keyera’s fractionation PROJECT HISTORY and storage facility in Fort Saskatchewan. The Terminal was developed in response to the growth in propane production and allows for essential egress of propane June 2014 Construction commenced from Western Canada. It features a rail rack, rail storage spurs and above ground product storage facilities. The Terminal has a Aug 2015 Operations begin capacity of 42,000 Bbls/d. Josephburg has several upstream and downstream pipeline connections enabling high and low vapour pressure products to be handled at the Terminal. Connections include but are not limited to the Fort Saskatchewan Facilities pipelines and Fort Saskatchewan Condensate System. The Josephburg terminal is located near Fort Saskatchewan, Alberta. Main : 780-912-2450 24-hour emergency: 1-800-661-5642 www.keyera.com -

Municipal Interface

Featured in this Issue: Collaboration • City of Edmonton Deploys Video to Collaborate More Effi ciently • MISA BC Fall Conference & Trade Show • La loi canadienne anti-pourriel (CAS L) Municipal Interface CANADA National Professional Journal of MISA/ASIM Canada JUNE 2013, VOL. 20, NO. 3 MISA Prairies Spring Conference Points to New Value Statements for IT The MISA Prairies 2013 Spring Conference in Banff, Alberta, more than lived up to its theme, “The Value of IT.” Page 12 Looking for Survey Plans? We’ve got them! Teranet and Land Survey Records now have survey plan images available through Plans mapped GeoWarehouse.ca to PIN! Great news! Teranet and Land Survey Records have created an indexed listing of survey plan images to PIN. As a GeoWarehouse user, you’ll be proactively notified that survey plan images are available for a property. A quick search shows the list of plans, and allows for layering of the associated PINS on the map. Automatic Teranet Enterprises Inc. Notification! [email protected] 416 643 1144 Land Survey Records Inc. [email protected] 1 888 809 5513 Actual online images are in colour. GeoWarehouse is a product of Teranet Real Estate Information Solutions 615698_Teranet.indd 1 24/01/13 5:47 PM If we can show a major insurance company how to save two million dollars a year, imagine what we can do for you. The possibilities for your business are endless — as long as you have imagination to guide you. Ricoh can help optimize how your company manages digital and paper-based information, giving you intelligent workflow solutions to help your business work better, faster, and more efficiently. -

2018 Municipal Affairs Population List | Cities 1

2018 Municipal Affairs Population List | Cities 1 Alberta Municipal Affairs, Government of Alberta November 2018 2018 Municipal Affairs Population List ISBN 978-1-4601-4254-7 ISSN 2368-7320 Data for this publication are from the 2016 federal census of Canada, or from the 2018 municipal census conducted by municipalities. For more detailed data on the census conducted by Alberta municipalities, please contact the municipalities directly. © Government of Alberta 2018 The publication is released under the Open Government Licence. This publication and previous editions of the Municipal Affairs Population List are available in pdf and excel version at http://www.municipalaffairs.alberta.ca/municipal-population-list and https://open.alberta.ca/publications/2368-7320. Strategic Policy and Planning Branch Alberta Municipal Affairs 17th Floor, Commerce Place 10155 - 102 Street Edmonton, Alberta T5J 4L4 Phone: (780) 427-2225 Fax: (780) 420-1016 E-mail: [email protected] Fax: 780-420-1016 Toll-free in Alberta, first dial 310-0000. Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 4 2018 Municipal Census Participation List .................................................................................... 5 Municipal Population Summary ................................................................................................... 5 2018 Municipal Affairs Population List ....................................................................................... -

St2 St9 St1 St3 St2

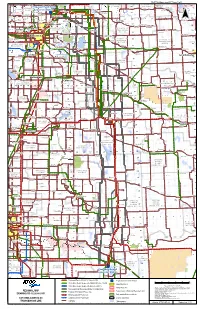

! SUPP2-Attachment 07 Page 1 of 8 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! .! ! ! ! ! ! SM O K Y L A K E C O U N T Y O F ! Redwater ! Busby Legal 9L960/9L961 57 ! 57! LAMONT 57 Elk Point 57 ! COUNTY ST . P A U L Proposed! Heathfield ! ! Lindbergh ! Lafond .! 56 STURGEON! ! COUNTY N O . 1 9 .! ! .! Alcomdale ! ! Andrew ! Riverview ! Converter Station ! . ! COUNTY ! .! . ! Whitford Mearns 942L/943L ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 56 ! 56 Bon Accord ! Sandy .! Willingdon ! 29 ! ! ! ! .! Wostok ST Beach ! 56 ! ! ! ! .!Star St. Michael ! ! Morinville ! ! ! Gibbons ! ! ! ! ! Brosseau ! ! ! Bruderheim ! . Sunrise ! ! .! .! ! ! Heinsburg ! ! Duvernay ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! 18 3 Beach .! Riviere Qui .! ! ! 4 2 Cardiff ! 7 6 5 55 L ! .! 55 9 8 ! ! 11 Barre 7 ! 12 55 .! 27 25 2423 22 ! 15 14 13 9 ! 21 55 19 17 16 ! Tulliby¯ Lake ! ! ! .! .! 9 ! ! ! Hairy Hill ! Carbondale !! Pine Sands / !! ! 44 ! ! L ! ! ! 2 Lamont Krakow ! Two Hills ST ! ! Namao 4 ! .Fort! ! ! .! 9 ! ! .! 37 ! ! . ! Josephburg ! Calahoo ST ! Musidora ! ! .! 54 ! ! ! 2 ! ST Saskatchewan! Chipman Morecambe Myrnam ! 54 54 Villeneuve ! 54 .! .! ! .! 45 ! .! ! ! ! ! ! ST ! ! I.D. Beauvallon Derwent ! ! ! ! ! ! ! STRATHCONA ! ! !! .! C O U N T Y O F ! 15 Hilliard ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! N O . 1 3 St. Albert! ! ST !! Spruce ! ! ! ! ! !! !! COUNTY ! TW O HI L L S 53 ! 45 Dewberry ! ! Mundare ST ! (ELK ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! . ! ! Clandonald ! ! N O . 2 1 53 ! Grove !53! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ISLAND) ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Ardrossan -

Message from Your Mayor and County Council

Strathconaona CounCountyCou 2009 Annual Report recap ReportLiving to the Community July 2010 Message from your Mayor and County Council staying the strategic course… in uncertain times In this edition of Strathcona In 2009, Council updated Strathcona County’s County Living, we present Strategic Plan. This plan has, and will continue to our Report to the Community guide us in creating and maintaining a prosperous, — a digest of some of our sustainable community, based on applying balanced key accomplishments of the social, economic and environmental perspectives to last year, and progress into our planning and decision making. 2010. This issue complements We continue to consult with our residents and Mayor Cathy Olesen the Strathcona County businesses across our sphere of responsibilities and 2009 Annual Report, which work proactively to put in place, maintain and presents Financial Statements for the year ended improve the services, infrastructure and facilities Strathcona County Alberta, Canada December 31, 2009. we need in balance with growth and demand. The world recession of 2008-2009 was certainly felt We are also working closely with neighbouring here in Alberta. In Strathcona County, businesses municipalities at coordinating planning and select and individuals have been affected to varying services to improve the quality of life in the County degrees. While still somewhat of a roller coaster on and the region. the global front, things are beginning to look up at All in all, Strathcona County’s fi nancial outlook staying the strategic course… in uncertain times home and economic recovery has begun. remains strong and continues to position the County For the most part, Strathcona County was able to well for the future. -

Regular Council Meeting May 28, 2012 4:00 P.M. to Be Held in Council Chambers Page

Regular Council Meeting May 28, 2012 4:00 p.m. To be held in Council Chambers Page 1. Call To Order 2. Opening Prayer ● Led by Pastor Dan Sudfield of the Mission Church 3. Public Hearing 4. Adoption of Agenda and Added Items 5. Minutes 4-10 a) Minutes - Presented by Alderman Joe Branco Motion Proposed By Administration: (I Move) That Council approve the Minutes for the May 14, 2012 Regular Council Meeting. 6. Delegations 11-119 a) LPS Aviation Report - Presented by Alderman Mark McFaul Motion Proposed By Administration: (I Move) That City Council accept the presentation and report from LPS Aviation as Information. 7. Department Reports 120-131 a) Monthly Financial Report - Presented By: Alderman Patricia MacQuarrie Motion Proposed By Administration (I Move) That City Council receive the financial report as presented for the period ending April 30, 2012. 132-139 b) Department Reports - Presented by Alderman Glenn Ruecker Motion Proposed By Administration: (I Move) That Council receive the department reports as information. 8. Council Reports 140-149 a) Commitee Report - Presented by Alderman Dale Crabtree Motion Proposed by Administration : (I Move) that the JEDI Committee Report be accpted as information. Page 1 of 177 Page 9. Bylaws 10. Development and Subdivision Agreements 11. Tenders 12. New and Unfinished Business 150-152 a) Request for Road Closure - Presented by Alderman Barry Hawkes Motion Proposed By Administration: (I Move) That City Council authorize the road closure on 50 Street between 46 and 47 Avenues with the conditions that the hydrants on the corners of 46 Avenue and 47 Avenue remain accessible to the fire department and that there be no impairments to their movements on 46 and 47 Avenues. -

FOR SALE Fort Saskatchewan Industrial Land ±99.86 Acres

FOR SALE Fort Saskatchewan Industrial Land ±99.86 Acres Range Road 220 & North of Township Road 550 Fort Saskatchewan, AB $14,979,000($150,000/Acre) Property • The subject lands are located on Range Road 220 and North of Township Road 550 in Fort Saskatchewan, Alberta - within the Alberta Industrial Heartland. • Alberta’s Industrial Heartland is one of the world’s most attractive locations for chemical, petrochemical, oil and gas investments. It is also Canada’s largest hydrocarbon processing regions. The region’s 40+ companies, several being world scale; provide fuels, fertilizers, power, petrochemicals and more to provincial and global customers. • Ongoing development continues on many projects in the Alberta Industrial Heartland and Sturgeon County. For more information on the Heartland visit industrialheartland.com • Vendor financing available. Karim Bensalah Scott Hughes RE/MAX Commercial Capital Associate Broker/Owner #300, 10171 Saskatchewan Drive 780 729 4382 780 915 7895 Edmonton, AB T6E 4R5 [email protected] [email protected] 780 757 1010 For Sale RR 220 & TWP RD 550 www.rcedm.ca Site Map The subject lands are part of the 2010-2030 Municipal Development by the City of Fort Saskatchewan. Fort Saskatchewan’s heavy industrial land base is located on the North side of Highway 15, to the North East of Downtown (shown in the dark grey). On the South side of Highway 15, Fort Saskatchewan has designated light and medium industrial lands to support the existing and emerging local and regional industries in Fort Saskatchewan and the Alberta Industrial Heartland. For Sale RR 220 & TWP RD 550 www.rcedm.ca The subject lands are situated on Range Road 220 and North of Township Road 550 with easy access to Fort Saskatchewan via Township Road 550. -

Published Local Histories

ALBERTA HISTORIES Published Local Histories assembled by the Friends of Geographical Names Society as part of a Local History Mapping Project (in 1995) May 1999 ALBERTA LOCAL HISTORIES Alphabetical Listing of Local Histories by Book Title 100 Years Between the Rivers: A History of Glenwood, includes: Acme, Ardlebank, Bancroft, Berkeley, Hartley & Standoff — May Archibald, Helen Bircham, Davis, Delft, Gobert, Greenacres, Kia Ora, Leavitt, and Brenda Ferris, e , published by: Lilydale, Lorne, Selkirk, Simcoe, Sterlingville, Glenwood Historical Society [1984] FGN#587, Acres and Empires: A History of the Municipal District of CPL-F, PAA-T Rocky View No. 44 — Tracey Read , published by: includes: Glenwood, Hartley, Hillspring, Lone Municipal District of Rocky View No. 44 [1989] Rock, Mountain View, Wood, FGN#394, CPL-T, PAA-T 49ers [The], Stories of the Early Settlers — Margaret V. includes: Airdrie, Balzac, Beiseker, Bottrell, Bragg Green , published by: Thomasville Community Club Creek, Chestermere Lake, Cochrane, Conrich, [1967] FGN#225, CPL-F, PAA-T Crossfield, Dalemead, Dalroy, Delacour, Glenbow, includes: Kinella, Kinnaird, Thomasville, Indus, Irricana, Kathyrn, Keoma, Langdon, Madden, 50 Golden Years— Bonnyville, Alta — Bonnyville Mitford, Sampsontown, Shepard, Tribune , published by: Bonnyville Tribune [1957] Across the Smoky — Winnie Moore & Fran Moore, ed. , FGN#102, CPL-F, PAA-T published by: Debolt & District Pioneer Museum includes: Bonnyville, Moose Lake, Onion Lake, Society [1978] FGN#10, CPL-T, PAA-T 60 Years: Hilda’s Heritage, -

Wildlife Regulation

Province of Alberta WILDLIFE ACT WILDLIFE REGULATION Alberta Regulation 143/1997 With amendments up to and including Alberta Regulation 148/2013 Office Consolidation © Published by Alberta Queen’s Printer Alberta Queen’s Printer 5th Floor, Park Plaza 10611 - 98 Avenue Edmonton, AB T5K 2P7 Phone: 780-427-4952 Fax: 780-452-0668 E-mail: [email protected] Shop on-line at www.qp.alberta.ca Copyright and Permission Statement Alberta Queen's Printer holds copyright on behalf of the Government of Alberta in right of Her Majesty the Queen for all Government of Alberta legislation. Alberta Queen's Printer permits any person to reproduce Alberta’s statutes and regulations without seeking permission and without charge, provided due diligence is exercised to ensure the accuracy of the materials produced, and Crown copyright is acknowledged in the following format: © Alberta Queen's Printer, 20__.* *The year of first publication of the legal materials is to be completed. Note All persons making use of this consolidation are reminded that it has no legislative sanction, that amendments have been embodied for convenience of reference only. The official Statutes and Regulations should be consulted for all purposes of interpreting and applying the law. (Consolidated up to 148/2013) ALBERTA REGULATION 143/97 Wildlife Act WILDLIFE REGULATION Table of Contents Interpretation and Application 1 Establishment of certain provisions by Lieutenant Governor in Council 2 Establishment of remainder by Minister 3 Interpretation 4 Interpretation for purposes of the Act 5 Exemptions and exclusions from Act and Regulation 6 Prevalence of Schedule 1 7 Application to endangered animals Part 1 Administration 8 Terms and conditions of approvals, etc.