Will There Be a New Era in Tajik-Uzbek Relations?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Central Asia in a Reconnecting Eurasia Kyrgyzstan’S Evolving Foreign Economic and Security Interests

JUNE 2015 1616 Rhode Island Avenue NW Washington, DC 20036 202-887-0200 | www.csis.org Lanham • Boulder • New York • London 4501 Forbes Boulevard Lanham, MD 20706 301- 459- 3366 | www.rowman.com Central Asia in a Reconnecting Eurasia Kyrgyzstan’s Evolving Foreign Economic and Security Interests AUTHORS Andrew C. Kuchins Jeffrey Mankoff Oliver Backes A Report of the CSIS Russia and Eurasia Program ISBN 978-1-4422-4100-8 Ë|xHSLEOCy241008z v*:+:!:+:! Cover photo: Labusova Olga, Shutterstock.com. Blank Central Asia in a Reconnecting Eurasia Kyrgyzstan’s Evolving Foreign Economic and Security Interests AUTHORS Andrew C. Kuchins Jeffrey Mankoff Oliver Backes A Report of the CSIS Rus sia and Eurasia Program June 2015 Lanham • Boulder • New York • London 594-61689_ch00_3P.indd 1 5/7/15 10:33 AM hn hk io il sy SY eh ek About CSIS hn hk io il sy SY eh ek For over 50 years, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) has worked to hn hk io il sy SY eh ek develop solutions to the world’s greatest policy challenges. Today, CSIS scholars are hn hk io il sy SY eh ek providing strategic insights and bipartisan policy solutions to help decisionmakers chart hn hk io il sy SY eh ek a course toward a better world. hn hk io il sy SY eh ek CSIS is a nonprofit or ga ni za tion headquartered in Washington, D.C. The Center’s 220 full- time staff and large network of affiliated scholars conduct research and analy sis and hn hk io il sy SY eh ek develop policy initiatives that look into the future and anticipate change. -

Soviet Central Asia and the Preservation of History

humanities Article Soviet Central Asia and the Preservation of History Craig Benjamin Frederik J Meijer Honors College, Grand Valley State University, Allendale, MI 49401, USA; [email protected] Received: 23 May 2018; Accepted: 9 July 2018; Published: 20 July 2018 Abstract: Central Asia has one of the deepest and richest histories of any region on the planet. First settled some 6500 years ago by oasis-based farming communities, the deserts, steppe and mountains of Central Asia were subsequently home to many pastoral nomadic confederations, and also to large scale complex societies such as the Oxus Civilization and the Parthian and Kushan Empires. Central Asia also functioned as the major hub for trans-Eurasian trade and exchange networks during three distinct Silk Roads eras. Throughout much of the second millennium of the Common Era, then under the control of a succession of Turkic and Persian Islamic dynasties, already impressive trading cities such as Bukhara and Samarkand were further adorned with superb madrassas and mosques. Many of these suffered destruction at the hands of the Mongols in the 13th century, but Timur and his Timurid successors rebuilt the cities and added numerous impressive buildings during the late-14th and early-15th centuries. Further superb buildings were added to these cities by the Shaybanids during the 16th century, yet thereafter neglect by subsequent rulers, and the drying up of Silk Roads trade, meant that, by the mid-18th century when expansive Tsarist Russia began to incorporate these regions into its empire, many of the great pre- and post-Islamic buildings of Central Asia had fallen into ruin. -

Tajikistan Asht Iran China Afghanistan Khujand

Mongolia Uzbekistan Kyrgyzstan Tu rkmenistan T a jikistan Tajikistan Asht Iran China Afghanistan Khujand Pakistan Nepal Bhutan Oman Arabian Bangladesh Sea India Burma ajikistan is a landlocked country in Central Tha Asia with a population of 7 million, and Ind i a n Ocean Rasht Sri Lanka a per capita income of US$410 a year, or Vahdat justT more than US$1 a day. The economy, which has TA JIKISTAN Dushanbe been growing an annual average at 8 percent during Norak 2000-06, depends heavily on exports of cotton and aluminum, and on growing remittances of its citizens in Russia. Poverty, although declining, remains alarmingly high. In 2005, almost six of every 10 Kumsangir people in Tajikistan live in extreme poverty. Current Build Sites Tajikistan remains the poorest and most economically fragile of the former Soviet countries. Since 1991, Tajikistan has experienced high levels of emigration, motivated by COUNTRY FACTS war following independence and, lately, by economic factors. Labor migrants’ remittances have played an important role as one of the drivers of Tajikistan’s robust Population: 7,211,884 (July 2008 est.) ........................................................... economic growth during the past several years. The volume of official remittances Capital: Dushanbe has significantly increased since 2001 and was estimated at $1.5 billion (36 percent ........................................................... of GDP) in 2007. Area: 55,251 sq miles .......................................................... Ethnic groups: Tajik 79.9%, Uzbek Due to armed conflict and ensuing economic collapse, housebuilding 15.3%, Russian 1.1%, Kyrgyz 1.1%, in Tajikistan has all but come to a halt. Unfinished homes are scattered across Tajikistan while existing housing stock deteriorates due to neglect. -

2012 Annual Report

U.S. Commission on InternationalUSCIRF Religious Freedom Annual Report 2012 Front Cover: Nearly 3,000 Egyptian mourners gather in central Cairo on October 13, 2011 in honor of Coptic Christians among 25 people killed in clashes during a demonstration over an attack on a church. MAHMUD HAMS/AFP/Getty Images Annual Report of the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom March 2012 (Covering April 1, 2011 – February 29, 2012) Commissioners Leonard A. Leo Chair Dr. Don Argue Dr. Elizabeth H. Prodromou Vice Chairs Felice D. Gaer Dr. Azizah al-Hibri Dr. Richard D. Land Dr. William J. Shaw Nina Shea Ted Van Der Meid Ambassador Suzan D. Johnson Cook, ex officio, non-voting member Ambassador Jackie Wolcott Executive Director Professional Staff David Dettoni, Director of Operations and Outreach Judith E. Golub, Director of Government Relations Paul Liben, Executive Writer John G. Malcolm, General Counsel Knox Thames, Director of Policy and Research Dwight Bashir, Deputy Director for Policy and Research Elizabeth K. Cassidy, Deputy Director for Policy and Research Scott Flipse, Deputy Director for Policy and Research Sahar Chaudhry, Policy Analyst Catherine Cosman, Senior Policy Analyst Deborah DuCre, Receptionist Tiffany Lynch, Senior Policy Analyst Jacqueline A. Mitchell, Executive Coordinator U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom 800 North Capitol Street, NW, Suite 790 Washington, DC 20002 202-523-3240, 202-523-5020 (fax) www.uscirf.gov Annual Report of the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom March 2012 (Covering April 1, 2011 – February 29, 2012) Table of Contents Overview of Findings and Recommendations……………………………………………..1 Introduction…………………………………………………………………………..1 Countries of Particular Concern and the Watch List…………………………………2 Overview of CPC Recommendations and Watch List……………………………….6 Prisoners……………………………………………………………………………..12 USCIRF’s Role in IRFA Implementation…………………………………………………14 Selected Accomplishments…………………………………………………………..15 Engaging the U.S. -

Federal Research Division Country Profile: Tajikistan, January 2007

Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Country Profile: Tajikistan, January 2007 COUNTRY PROFILE: TAJIKISTAN January 2007 COUNTRY Formal Name: Republic of Tajikistan (Jumhurii Tojikiston). Short Form: Tajikistan. Term for Citizen(s): Tajikistani(s). Capital: Dushanbe. Other Major Cities: Istravshan, Khujand, Kulob, and Qurghonteppa. Independence: The official date of independence is September 9, 1991, the date on which Tajikistan withdrew from the Soviet Union. Public Holidays: New Year’s Day (January 1), International Women’s Day (March 8), Navruz (Persian New Year, March 20, 21, or 22), International Labor Day (May 1), Victory Day (May 9), Independence Day (September 9), Constitution Day (November 6), and National Reconciliation Day (November 9). Flag: The flag features three horizontal stripes: a wide middle white stripe with narrower red (top) and green stripes. Centered in the white stripe is a golden crown topped by seven gold, five-pointed stars. The red is taken from the flag of the Soviet Union; the green represents agriculture and the white, cotton. The crown and stars represent the Click to Enlarge Image country’s sovereignty and the friendship of nationalities. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND Early History: Iranian peoples such as the Soghdians and the Bactrians are the ethnic forbears of the modern Tajiks. They have inhabited parts of Central Asia for at least 2,500 years, assimilating with Turkic and Mongol groups. Between the sixth and fourth centuries B.C., present-day Tajikistan was part of the Persian Achaemenian Empire, which was conquered by Alexander the Great in the fourth century B.C. After that conquest, Tajikistan was part of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, a successor state to Alexander’s empire. -

Central Asia: Confronting Independence

THE JAMES A. BAKER III INSTITUTE FOR PUBLIC POLICY OF RICE UNIVERSITY UNLOCKING THE ASSETS: ENERGY AND THE FUTURE OF CENTRAL ASIA AND THE CAUCASUS CENTRAL ASIA: CONFRONTING INDEPENDENCE MARTHA BRILL OLCOTT SENIOR RESEARCH ASSOCIATE CARNEGIE ENDOWMENT FOR INTERNATIONAL PEACE PREPARED IN CONJUNCTION WITH AN ENERGY STUDY BY THE CENTER FOR INTERNATIONAL POLITICAL ECONOMY AND THE JAMES A. BAKER III INSTITUTE FOR PUBLIC POLICY RICE UNIVERSITY – APRIL 1998 CENTRAL ASIA: CONFRONTING INDEPENDENCE Introduction After the euphoria of gaining independence settles down, the elites of each new sovereign country inevitably stumble upon the challenges of building a viable state. The inexperienced governments soon venture into unfamiliar territory when they have to formulate foreign policy or when they try to forge beneficial economic ties with foreign investors. What often proves especially difficult is the process of redefining the new country's relationship with its old colonial ruler or federation partners. In addition to these often-encountered hurdles, the newly independent states of Central Asia-- Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan-- have faced a host of particular challenges. Some of these emanate from the Soviet legacy, others--from the ethnic and social fabric of each individual polity. Yet another group stems from the peculiarities of intra- regional dynamics. Finally, the fledgling states have been struggling to step out of their traditional isolation and build relations with states outside of their neighborhood. This paper seeks to offer an overview of all the challenges that the Central Asian countries have confronted in the process of consolidating their sovereignty. The Soviet Legacy and the Ensuing Internal Challenges What best distinguishes the birth of the Central Asian states from that of any other sovereign country is the incredible weakness of pro-independence movements throughout the region. -

Agreement Between the Government of Republic of Tajikistan and the Government of the United Arab Emirates for the Promotion and Protection of Investments

Agreement between the Government of Republic of Tajikistan and the Government of the United Arab Emirates for the Promotion and Protection of Investments The Government of the Republic of Tajikistan and the Government of the United Arab Emirates ( both countries hereinafter collectively referred to as the Contracting Parties and each referred to as a Contracting Party).; Desiring to create favourable conditions for greater economic cooperation between them and particularly for investments by investors of one Contracting Party in the territory of the other Contracting Party. Recognizing that the reciprocal protection of such investments will be conductive to the stimulation of business initiative and will increase prosperity in both Contracting Parties. Have agreed as follows:- Article 1. Definitions For the purpose of this Agreement:- (1) The term "investment" shall comprise every kind of asset invested by the Government or by a natural or legal person of one Contracting Party in the territory of the other Contracting Party in accordance with the laws, regulations and administrative practices of that Contracting Party. Without restricting the generality of the forgoing the term "investment" shall include: (a) Movable and immovable property as well as any other property rights in rem such as mortgages, liens, pledges, usufruct and similar rights; (b) Shares, stocks and debentures of companies or other rights or interests in such companies, loans related to investments and bonds issued by a Contracting Party or any of its natural or legal -

Could Uzbekistan Lead Central Asia?

Could Uzbekistan Lead Central Asia? In surprise move, previously isolated state calls for tighter regional integration. Uzbek president Shavkat Mirziyoyev. (Photo: Uzbek president’s press service) Uzbek president Shavkat Mirziyoyev has called for closer cooperation between all five countries of Central Asia in a move which some believe signals a new and more vigorous regional role for Tashkent. At an international conference on the Central Asia’s future, held in the historic Uzbek city of Samarkand in early November, Mirziyoyev emphasised that he supported efforts to create “a stable, economically developed and thriving region”. “I am sure that all will win from this – both the Central Asian states and other countries,” Mirziyoyev told the event, held under the auspices of the UN and attended by senior officials, diplomats and experts from the region, the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), and further afield. The event itself and Mirziyoyev’s address were both unusual. Initial attempts at regional unity following the fall of the Soviet Union were short-lived. For more than a decade the five states have not seriously discussed cooperating on domestic development and remain embroiled in disputes over water resources, borders and market protectionism amid general mistrust between the leadership. In fact, it was Uzbekistan, under the rule of former president Islam Karimov, which was the most sceptical about regional cooperation. As the successor to Karimov, who died in September 2016, Mirziyoyev has taken a number of measures that appear to show willingness to open up one of the world’s most isolated states. (See Could Uzbekistan be Opening Up?). -

The Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan Border: a Legacy of Soviet Imperialism

Undergraduate Journal of Global Citizenship Volume 4 Issue 1 Article 4 6-1-2021 The Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan Border: A Legacy of Soviet Imperialism Liam Abbate Santa Clara University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fairfield.edu/jogc Recommended Citation Abbate, Liam (2021) "The Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan Border: A Legacy of Soviet Imperialism," Undergraduate Journal of Global Citizenship: Vol. 4 : Iss. 1 , Article 4. Available at: https://digitalcommons.fairfield.edu/jogc/vol4/iss1/4 This item has been accepted for inclusion in DigitalCommons@Fairfield by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Fairfield. It is brought to you by DigitalCommons@Fairfield with permission from the rights- holder(s) and is protected by copyright and/or related rights. You are free to use this item in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses, you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abbate: The Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan Border: A Legacy of Soviet Imperialism dispute, particularly in relation to the U.S.- The Kyrgyzstan- China rivalry. Uzbekistan Border: Background A Legacy of Soviet Kyrgyzstan is among the poorest of the nations of Central Asia: its per capita is a Imperialism mere tenth of its larger neighbor LIAM ABBATE Kazakhstan.1 Formerly a constituent republic of the Union of the Soviet Socialist Republics, the Kirghiz Soviet Socialist Republic declared independence as Abstract Kyrgyzstan on August 31, 1991. -

Country Codes and Currency Codes in Research Datasets Technical Report 2020-01

Country codes and currency codes in research datasets Technical Report 2020-01 Technical Report: version 1 Deutsche Bundesbank, Research Data and Service Centre Harald Stahl Deutsche Bundesbank Research Data and Service Centre 2 Abstract We describe the country and currency codes provided in research datasets. Keywords: country, currency, iso-3166, iso-4217 Technical Report: version 1 DOI: 10.12757/BBk.CountryCodes.01.01 Citation: Stahl, H. (2020). Country codes and currency codes in research datasets: Technical Report 2020-01 – Deutsche Bundesbank, Research Data and Service Centre. 3 Contents Special cases ......................................... 4 1 Appendix: Alpha code .................................. 6 1.1 Countries sorted by code . 6 1.2 Countries sorted by description . 11 1.3 Currencies sorted by code . 17 1.4 Currencies sorted by descriptio . 23 2 Appendix: previous numeric code ............................ 30 2.1 Countries numeric by code . 30 2.2 Countries by description . 35 Deutsche Bundesbank Research Data and Service Centre 4 Special cases From 2020 on research datasets shall provide ISO-3166 two-letter code. However, there are addi- tional codes beginning with ‘X’ that are requested by the European Commission for some statistics and the breakdown of countries may vary between datasets. For bank related data it is import- ant to have separate data for Guernsey, Jersey and Isle of Man, whereas researchers of the real economy have an interest in small territories like Ceuta and Melilla that are not always covered by ISO-3166. Countries that are treated differently in different statistics are described below. These are – United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland – France – Spain – Former Yugoslavia – Serbia United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. -

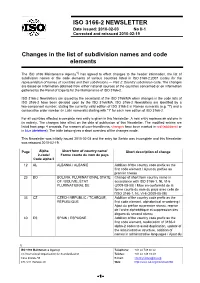

ISO 3166-2 NEWSLETTER Changes in the List of Subdivision Names And

ISO 3166-2 NEWSLETTER Date issued: 2010-02-03 No II-1 Corrected and reissued 2010-02-19 Changes in the list of subdivision names and code elements The ISO 3166 Maintenance Agency1) has agreed to effect changes to the header information, the list of subdivision names or the code elements of various countries listed in ISO 3166-2:2007 Codes for the representation of names of countries and their subdivisions — Part 2: Country subdivision code. The changes are based on information obtained from either national sources of the countries concerned or on information gathered by the Panel of Experts for the Maintenance of ISO 3166-2. ISO 3166-2 Newsletters are issued by the secretariat of the ISO 3166/MA when changes in the code lists of ISO 3166-2 have been decided upon by the ISO 3166/MA. ISO 3166-2 Newsletters are identified by a two-component number, stating the currently valid edition of ISO 3166-2 in Roman numerals (e.g. "I") and a consecutive order number (in Latin numerals) starting with "1" for each new edition of ISO 3166-2. For all countries affected a complete new entry is given in this Newsletter. A new entry replaces an old one in its entirety. The changes take effect on the date of publication of this Newsletter. The modified entries are listed from page 4 onwards. For reasons of user-friendliness, changes have been marked in red (additions) or in blue (deletions). The table below gives a short overview of the changes made. This Newsletter was initially issued 2010-02-03 and the entry for Serbia was incomplete and this Newsletter was reissued 2010-02-19. -

Leadership Transition in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan Implications for Policy and Stability in Central Asia

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Calhoun, Institutional Archive of the Naval Postgraduate School Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Theses and Dissertations Thesis Collection 2007-09 Leadership transition in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan implications for policy and stability in Central Asia Smith, Shane A. Monterey, California. Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/3204 NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY, CALIFORNIA THESIS LEADERSHIP TRANSITION IN KAZAKHSTAN AND UZBEKISTAN: IMPLICATIONS FOR POLICY AND STABILITY IN CENTRAL ASIA by Shane A. Smith September 2007 Thesis Advisor: Thomas H. Johnson Second Reader: James A. Russell Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188) Washington DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED September 2007 Master’s Thesis 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE Leadership Transition in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan: 5. FUNDING NUMBERS Implications for Policy and Stability in Central Asia 6.