Royalty, Religion and Rust!

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LCA Introduction

The Hambleton and Howardian Hills CAN DO (Cultural and Natural Development Opportunity) Partnership The CAN DO Partnership is based around a common vision and shared aims to develop: An area of landscape, cultural heritage and biodiversity excellence benefiting the economic and social well-being of the communities who live within it. The organisations and agencies which make up the partnership have defined a geographical area which covers the south-west corner of the North York Moors National Park and the northern part of the Howardian Hills Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. The individual organisations recognise that by working together resources can be used more effectively, achieving greater value overall. The agencies involved in the CAN DO Partnership are – the North York Moors National Park Authority, the Howardian Hills Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, English Heritage, Natural England, Forestry Commission, Environment Agency, Framework for Change, Government Office for Yorkshire and the Humber, Ryedale District Council and Hambleton District Council. The area was selected because of its natural and cultural heritage diversity which includes the highest concentration of ancient woodland in the region, a nationally important concentration of veteran trees, a range of other semi-natural habitats including some of the most biologically rich sites on Jurassic Limestone in the county, designed landscapes, nationally important ecclesiastical sites and a significant concentration of archaeological remains from the Neolithic to modern times. However, the area has experienced the loss of many landscape character features over the last fifty years including the conversion of land from moorland to arable and the extensive planting of conifers on ancient woodland sites. -

England | HIKING COAST to COAST LAKES, MOORS, and DALES | 10 DAYS June 26-July 5, 2021 September 11-20, 2021

England | HIKING COAST TO COAST LAKES, MOORS, AND DALES | 10 DAYS June 26-July 5, 2021 September 11-20, 2021 TRIP ITINERARY 1.800.941.8010 | www.boundlessjourneys.com How we deliver THE WORLD’S GREAT ADVENTURES A passion for travel. Simply put, we love to travel, and that Small groups. Although the camaraderie of a group of like- infectious spirit is woven into every one of our journeys. Our minded travelers often enhances the journey, there can be staff travels the globe searching out hidden-gem inns and too much of a good thing! We tread softly, and our average lodges, taste testing bistros, trattorias, and noodle stalls, group size is just 8–10 guests, allowing us access to and discovering the trails and plying the waterways of each opportunities that would be unthinkable with a larger group. remarkable destination. When we come home, we separate Flexibility to suit your travel style. We offer both wheat from chaff, creating memorable adventures that will scheduled, small-group departures and custom journeys so connect you with the very best qualities of each destination. that you can choose which works best for you. Not finding Unique, award-winning itineraries. Our flexible, hand- exactly what you are looking for? Let us customize a journey crafted journeys have received accolades from the to fulfill your travel dreams. world’s most revered travel publications. Beginning from Customer service that goes the extra mile. Having trouble our appreciation for the world’s most breathtaking and finding flights that work for you? Want to surprise your interesting destinations, we infuse our journeys with the traveling companion with a bottle of champagne at a tented elements of adventure and exploration that stimulate our camp in the Serengeti to celebrate an important milestone? souls and enliven our minds. -

RIEVAULX ABBEY and ITS SOCIAL ENVIRONMENT, 1132-1300 Emilia

RIEVAULX ABBEY AND ITS SOCIAL ENVIRONMENT, 1132-1300 Emilia Maria JAMROZIAK Submitted in Accordance with the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of History September 2001 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to express my gratitude to my supervisor Dr Wendy Childs for her continuous help and encouragement at all stages of my research. I would also like to thank other faculty members in the School of History, in particular Professor David Palliser and Dr Graham Loud for their advice. My thanks go also to Dr Mary Swan and students of the Centre for Medieval Studies who welcomed me to the thriving community of medievalists. I would like to thank the librarians and archivists in the Brotherton Library Leeds, Bodleian Library Oxford, British Library in London and Public Record Office in Kew for their assistance. Many people outside the University of Leeds discussed several aspects of Rievaulx abbey's history with me and I would like to thank particularly Dr Janet Burton, Dr David Crouch, Professor Marsha Dutton, Professor Peter Fergusson, Dr Brian Golding, Professor Nancy Partner, Dr Benjamin Thompson and Dr David Postles as well as numerous participants of the conferences at Leeds, Canterbury, Glasgow, Nottingham and Kalamazoo, who offered their ideas and suggestions. I would like to thank my friends, Gina Hill who kindly helped me with questions about English language, Philip Shaw who helped me to draw the maps and Jacek Wallusch who helped me to create the graphs and tables. -

Blast Furnace

Blast furnace From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search Blast furnace in Sestao, Spain. The actual furnace itself is inside the centre girderwork. A blast furnace is a type of metallurgical furnace used for smelting to produce metals, generally iron. In a blast furnace, fuel and ore are continuously supplied through the top of the furnace, while air (sometimes with oxygen enrichment) is blown into the bottom of the chamber, so that the chemical reactions take place throughout the furnace as the material moves downward. The end products are usually molten metal and slag phases tapped from the bottom, and flue gases exiting from the top of the furnace. Blast furnaces are to be contrasted with air furnaces (such as reverberatory furnaces), which were naturally aspirated, usually by the convection of hot gases in a chimney flue. According to this broad definition, bloomeries for iron, blowing houses for tin, and smelt mills for lead, would be classified as blast furnaces. However, the term has usually been limited to those used for smelting iron ore to produce pig iron, an intermediate material used in the production of commercial iron and steel. Contents [hide] • 1 History o 1.1 China o 1.2 Ancient World elsewhere o 1.3 Medieval Europe o 1.4 Early modern blast furnaces: origin and spread o 1.5 Coke blast furnaces o 1.6 Modern furnaces • 2 Modern process • 3 Chemistry • 4 See also • 5 References o 5.1 Notes o 5.2 Bibliography • 6 External links [edit] History Blast furnaces existed in China from about the 5th century BC, and in the West from the High Middle Ages. -

Helmsley and Rievaulx Abbey

Helmsley and Rievaulx Abbey Rievaulx Abbey In 1131 a group of twelve French monks clad in long country walk, r ins white cloaks first set their eyes on a serene site located Classic omantic abbey ru deep in a wooded valley, nestled in the curve of the tranquil River Rye. They and their abbot, Stephen, set to and laid the foundations of what was to become the largest and richest Cistercian house in England. The monks cleared wasteland and forest, and built outlying granges, or farms, that supplied the abbey with food. The intriguing humps and bumps near Griff Farm are all that he route from the market town of Helmsley to Rievaulx Abbey is a well- now remains of Griff Grange, the abbey’s original ‘home Ttrodden one, but it never loses its capacity to delight and inspire. This farm’, where crops were grown to feed the brothers. At its 7-mile circular route climbs gently for sweeping views of town and castle height Rievaulx Abbey probably supported 140 monks before dropping down through charming bluebell woods to reach the and 500 lay brothers and servants. Such great wealth, peaceful village and tranquil ruins of Rievaulx Abbey. Either return the and the monastic obedience to Rome, led Henry VIII to same way, or complete a circuit – and take in more stupendous views – via dissolve the monasteries – Rievaulx was suppressed in dramatically sited Rievaulx Terrace and Griff Farm, high above the abbey. 1538 and left to decay. Evolution of an estate Did you know? Great for: history buffs, woodland wanders, The International In 1689, Sir Charles Duncombe, a wealthy London big-sky views, list-tickers Mike Kipling Centre for banker, bought the extensive Helmsley Estate, Length: 7 miles (11km) Birds of Prey at associated since medieval times with Helmsley Time: 4 hours Duncombe Park Castle. -

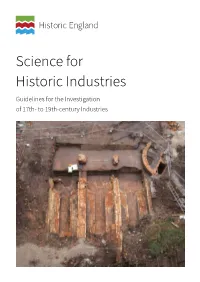

Science for Historic Industries Guidelines for the Investigation of 17Th- to 19Th-Century Industries Summary

Science for Historic Industries Guidelines for the Investigation of 17th- to 19th-century Industries Summary This guidance is intended to aid archaeologists working on sites of historic industries. For the purpose of this guidance ‘industries’ are non-domestic manufacturing activities (but not the production of foodstuffs) and ‘historic’ covers the period from the early 17th century to the late 19th century. The advice demonstrates the additional information that can be obtained by applying scientific techniques. Some of the issues explored are particularly relevant to urban sites, but the principles have wider application. Despite the crucial contribution that scientific techniques can make to archaeology, their application to the post-medieval and later periods has been rare (Crossley 1998). This guidance describes some of the techniques that are commonly used and include examples of the ways in which they have been, or could be, applied to the archaeological remains of historic industries. This is one of four Historic England publications concerning materials science and industrial processes: Archaeometallurgy Archaeological Evidence for Glassworking Archaeological and Historic Pottery Production Sites The previous edition of these guidelines was written and compiled by David Dungworth and Sarah Paynter, with contributions by Anna Badcock, David Barker, Justine Bayley, Alex Bayliss, Paul Belford, Gill Campbell, Tom Cromwell, David Crossley, Jonathan Goodwin, Cathy Groves, Derek Hamilton, Rob Ixer, Andrew Lines, Roderick Mackenzie, Ian Miller, Ronald A. Ross, James Symonds and Jane Wheeler. This edition was revised by David Dungworth and Florian Ströbele. This edition published by Historic England October 2018. All images © Historic England unless otherwise stated. Please refer to this document as: Historic England 2018 Science for Historic Industries: Guidelines for the Investigation of 17th- to 19th-century Industries. -

Rievaulx Abbey Teachers

HISTORY ALSO AVAILABLE TO DOWNLOAD TEACHER’S KIT HISTORY RIEVAULX ABBEY INFORMATION ACTIVITIES TEAchers’ InformaTION of opening religious life to the labouring and uneducated classes by introducing a new category Rievaulx Abbey was founded in 1132; the first of the known as lay brothers. Even some knights and nobles Cistercian order to be established in the north of joined Cistercian abbeys as lay brothers. England. It quickly became one of the wealthiest and spiritually renowned monasteries in medieval England. Lay brothers could be distinguished from the monks Under King Henry VIII, its monastic life ended and the by their clothes; the Cistercian monks wore undyed or buildings fell into ruins, only for the site to later flourish white habits, whereas lay brothers wore brown habits as a destination for artists and writers, inspired by and were also allowed beards. The monks spent much the remains. of their day in church singing the eight daily services or reading in the cloister, alongside some manual labour. Who were the Cistercians? Lay brothers undertook most of the agricultural labour on the granges (monastic farms), returning to the abbey The Cistercian Order was founded at Cîteaux in on Sundays and feast days. Lay brothers did take some Burgundy, eastern France in 1098. One of many new monastic vows but these were less detailed than those religious orders born at this time, their intention was of the monks. to adhere more closely to the Rule of St. Benedict – the blueprint for monastic life, written in the 540s. The monks and lay brothers would have lived quite a tough, strictly disciplined life; working hard and eating In 1119 Pope Calixtus II formally recognised the a simple vegetarian diet. -

Historic Environment Review News from the North York Moors National Park Authority 2009

historic environment review news from THE NORTH YORK MOORS NATIONAL PARK AuTHORITY 2009 INSIDE the Rievaulx timber – page 2 Introduction CO NTENTS This is the first Historic Environment Newsletter produced by the North York Moors The Rievaulx Timber 2 National Park Authority. In it we look at a range of projects which are underway or have been completed in the last year or so. We also include a number of topics about Lime and Ice 3 which we are frequently asked and which we hope you will find of interest. If you Staddle stones 4 have specific questions which you would like to raise, please contact us. Scotch Corner chapel 5 The North York Moors National Park contains thousands of archaeological sites which represent the activities of human beings in the area from the end of the last Ice Age John Collier collection 5 (c. 12,000 years ago) to important industrial landscapes of the 17th to early 20th Archaeology of the North York centuries and the concrete and steel bunkers of the Cold War – in fact some 32% of Moors: the human value 6-7 the nationally important protected archaeological sites (Scheduled Monuments) for Publications update 6-7 the Yorkshire and Humber region can be found in the National Park. Buildings also form an important part of the historic environment and the Stone trods 8 National Park contains 9% of the regional total of Listed (protected) Buildings. The Archaeology dayschool 9 National Park maintains a detailed index of all the known archaeological sites and nymnpA volunteer group 9 important buildings in the form of the Historic Environment Record (HER), which currently contains over twenty thousand records. -

Blast Furnace

Blast Furnace A blast furnace is a type of metallurgical furnace used for smelting to produce industrial metals, generally iron, but also others such as lead or copper. In a blast furnace, fuel, ores, and flux (limestone) are continuously supplied through the top of the furnace, while a hot blast of air (sometimes with oxygen enrichment) is blown into the lower section of the furnace through a series of pipes called tuyeres, so that the chemical reactions take place throughout the furnace as the material moves downward. The end products are usually molten metal and slag phases tapped from the bottom, and flue gases exiting from the top of the furnace. The downward flow of the ore and flux in contact with an upflow of hot, carbon monoxide-rich combustion gases is a countercurrent exchange and chemical reaction process.[1] In contrast, air furnaces (such as reverberatory furnaces) are naturally aspirated, usually by the convection of hot gases in a chimney flue. According to this broad definition, bloomeries for iron, blowing houses for tin, and smelt mills for leadwould be classified as blast furnaces. However, the term has usually been limited to those used for smelting iron ore to produce pig iron, an intermediate material used in the production of commercial iron and steel, and the shaft furnaces used in combination with sinter plants in base metals smelting. History Blast furnaces existed in China from about 1st century AD[4] and in the West from the High Middle Ages. They spread from the region around Namur in Wallonia (Belgium) in the late 15th century, being introduced to England in 1491. -

GENERAL INDEX to RYEDALE HISTORIANS Nos. I to XXIX

GENERAL INDEX TO RYEDALE HISTORIANS Nos. I to XXIX (Roman figures indicate number of the issue, Arabic the page). agriculture: monastic XV,16; XVII,5 Ainsley family: Bilsdale XV,12 aisled barn: medieval II,20 alehouses: IV,47 Ampleforth: marriage registers VI,60 Anglian: and Viking York IV,68 (review) remains, Cawthorn XX,5 Anglo-Saxon archbishops of York: VII,77 (review) Anglo-Saxon stone sculpture XVIII,3 (review); XXII,23 (review) Anglo-Saxon assembly places in Ryedale XXV,32 Appleton le Moors: medieval free chapel XIII,48 medieval oven XVIII,6 Shepherd family of XIX,4 a 12th century planned village (review) XXIII,42 murder at Little Hamley XXIV,9 Appleton le Street: church XX,24 aqueduct: Bonfield Gill I,45 (Notes and Queries) arable farming: medieval II,5 ; IV,63 (review); 19th century XVII,8 archaeological investigations, Levisham Moor VIII,33,35; XV,34 (review) at Village Farm Barn, Low Kilburn XXII,13 framework for, in NYMNP XXIII,13 Old Stables, Barker’s Yard, Helmsley XXVI,4 archaeology: National Park XV,7;XVI,9 prehistoric and Roman XII,52,XIX,6; XX,5 archbishopric estates: Civil War XI,26 (review) archbishops of York: Anglo-Saxon VII,27 (review) Arden Priory VIII,10 Ashburnham Clock Face: iron working VIII,45 Assembly places in Anglo-Saxon Ryedale XXV,32 Awmack Family of Harome XV,20 bank and ditch: Stonegrave X,70 Barker’s Yard, Helmsley, Archaeological Investigations XXVI,4 battle of Farndale VII,9 Baysdale Head: coal working XIII,62 beacons: N.E. Yorkshire XlV,3 Beadlam: Romano-British villa III,10; V,72; XIX,24 Beadlam: -

Researching Yorkshire Quaker History

Researching Yorkshire Quaker history A guide to sources Compiled by Helen E Roberts for the Yorkshire Quaker Heritage Project Published by The University of Hull Brynmor Jones Library 2003 (updated 2007) 1 The University of Hull 2003 Published by The University of Hull Brynmor Jones Library ISBN 0-9544497-0-3 Acknowledgements During the lifetime of this project, numerous people have contributed their time, enthusiasm and knowledge of Quaker history; I would like to thank those who volunteered to undertake name indexing of Quaker records, those who participated in the project conferences and those who offered information to the project survey. In particular I am grateful for the continued support and encouragement of Brian Dyson, Hull University Archivist, and Oliver Pickering, Deputy Head of Special Collections, Leeds University Library, as well as the other members of the project steering group. Thanks are due to the staff of the following archive offices and libraries whose collections are covered in this guide: Cumbria Record Office, Kendal, Doncaster Archives Department, Durham County Record Office, East Riding Archives and Records Service, Huddersfield University Library, Lancashire Record Office, Leeds University Library Department of Special Collections, the Library of the Religious Society of Friends, Sheffield Archives, West Yorkshire Archive Service, York City Archives and the Borthwick Institute of Historical Research, University of York, and to the archivists at Bootham School and The Mount School, York, and Ackworth School. The support of the Friends Historical Society, the Quaker Family History Society and the Quaker Studies Research Association is also acknowledged. The project received valuable assistance from the Historical Manuscripts Commission, through the good offices of Andrew Rowley. -

How the Monks Saved Civilization

Chapter Three How the Monks Saved Civilization he monks played a critical role in the development of Western civilization. But judging from Catholic monas- T ticism’s earliest practice, one would hardly have guessed the enormous impact on the outside world that it would come to exercise. This historical fact comes as less of a surprise when we recall Christ’s words: “Seek ye first the kingdom of heaven, and all these things shall be added unto you.” That, stated simply, is the history of the monks. Early forms of monastic life are evident by the third century. By then, individual Catholic women committed themselves as consecrated virgins to lives of prayer and sacrifice, looking after the poor and the sick.1 Nuns come from these early traditions. Another source of Christian monasticism is found in Saint Paul of Thebes and more famously in Saint Anthony of Egypt (also known as Saint Anthony of the Desert), whose life spanned the mid-third century through the mid-fourth century. Saint Anthony’s sister lived in a house of consecrated virgins. He became a hermit, retreating to the deserts of Egypt for the sake of Copyright © 2005 by Thomas E. Woods, Jr. 26 How the Catholic Church Built Western Civilization his own spiritual perfection, though his great example led thou- sands to flock to him. The hermit’s characteristic feature was his retreat into remote solitude, so that he might renounce worldly things and concen- trate intensely on his spiritual life. Hermits typically lived alone or in groups of two or three, finding shelter in caves or simple huts and supporting themselves on what they could produce in their small fields or through such tasks as basket-making.