С01чс0в01а

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alite's Archives: Bro Dadcagting from Ok the Outlaw Empirek

Big Changes In Amateur Service Rules On Page 65 D08635 APRIL 2000 4IP A Loo How WBT Folght Soviet Propaganda Alite's Archives: Bro_dadcagting From ok The Outlaw Empirek, cene, The Pirate's Den, I Got Started, And Much More! CARRY THE WORLD '''''',--4000.111111111P WITH YOU! s. r. Continuous Coverage: 145 100 kHz to 1299.99995* MHz! 1.i.1f:s1711711.:: 'Cellular telephone frequencies are docked and cannot be restored. VR-500 RECEIVER All Mode Reception: COMMUNICATIONS FM, Wide -FM, USB LSB, CW, and AM! Huge Memory Capacity: 1091 Channels! B.W P.SET Ultra Compact Size! STEP 58 mm x 24 mm x 95 mm SCHOCN MW/MC 220 g including Antenna / Battery) MEMO 1ozCP.. CD MODE PW Simulated display / keypad Illumination SCH/rmS . SW/SC S 40SET/NAMEIrk arso LAMP ' ATT Actual Size CODW CIO421,et Features *Multiple Power Source Capability Huge 1091-ch Memory System *Convenience Features *Direct Keypad Frequency Entry With Search & Scan 1 MHz Fast Steps Front-end 20 dB *Large High -Output Speaker Regular Memories 11000 ch) Attenuator RF Squelch 'Power On / Polycarbonate Case Search Band Memories10 ch) Power Off Timers Adjustable *Real -Time 60-ch* Band Scope Preset Channel Memories Battery Saver Extensive Menu `Range 6 MHz / Step 100 kHz (19 ch +10 Weather Channels` Customization Clone Capability ,',1.1F11 *Full Illumination For Dual Watch Memories (10 ch` Computer Control Display And Keypad Priority Memory (1 ch) COMMUNICATIONS RECEIVER Mb *Versatile Squelch / Smart SearchTM Memories as Monitor Key (11/21/31/41 ch) Ct--2 VR-500 *Convenient "Preset" All -Mode Wideband Receiver OD CD0 0 ®m Operating Mode gg YAE SU ©1999 Yaesu USA, 17210 Edwards Road. -

Dx Magazine 12/2003

12 - 2003 All times mentioned in this DX MAGAZINE are UTC - Alle Zeiten in diesem DX MAGAZINE sind UTC Staff of WORLDWIDE DX CLUB: PRESIDENT AND CHIEF EDITOR ..C WWDXC Headquarters, Michael Bethge, Postfach 12 14, D-61282 Bad Homburg, Germany B daytime +49-6102-2861, evening/weekend +49-6172-390918 F +49-6102-800999 E-Mail: [email protected] V Internet: http://www.wwdxc.de BROADCASTING NEWS EDITOR . C Dr. Jürgen Kubiak, Goltzstrasse 19, D-10781 Berlin, Germany E-Mail: [email protected] LOGBOOK EDITOR .............C Ashok Kumar Bose, Apt. #421, 3420 Morning Star Drive, Mississauga, ON, L4T 1X9, Canada V E-Mail: [email protected] QSL CORNER EDITOR ..........C Richard Lemke, 60 Butterfield Crescent, St. Albert, Alberta, T8N 2W7, Canada V E-Mail: [email protected] TOP NEWS EDITOR (Internet) ....C Wolfgang Büschel, Hoffeld, Sprollstrasse 87, D-70597 Stuttgart, Germany V E-Mail: [email protected] TREASURER & SECRETARY .....C Karin Bethge, Urseler Strasse 18, D-61348 Bad Homburg, Germany NEWCOMER SERVICE OF AGDX . C Hobby-Beratung, c/o AGDX, Postfach 12 14, D-61282 Bad Homburg, Germany (please enclose return postage) Each of the editors mentioned above is self-responsible for the contents of his composed column. Furthermore, we cannot be responsible for the contents of advertisements published in DX MAGAZINE. We have no fixed deadlines. Contributions may be sent either to WWDXC Headquarters or directly to our editors at any time. If you send your contributions to WWDXC Headquarters, please do not forget to write all contributions for the different sections on separate sheets of paper, so that we are able to distribute them to the competent section editors. -

Euromosaic III Touches Upon Vital Interests of Individuals and Their Living Conditions

Research Centre on Multilingualism at the KU Brussel E U R O M O S A I C III Presence of Regional and Minority Language Groups in the New Member States * * * * * C O N T E N T S Preface INTRODUCTION 1. Methodology 1.1 Data sources 5 1.2 Structure 5 1.3 Inclusion of languages 6 1.4 Working languages and translation 7 2. Regional or Minority Languages in the New Member States 2.1 Linguistic overview 8 2.2 Statistic and language use 9 2.3 Historical and geographical aspects 11 2.4 Statehood and beyond 12 INDIVIDUAL REPORTS Cyprus Country profile and languages 16 Bibliography 28 The Czech Republic Country profile 30 German 37 Polish 44 Romani 51 Slovak 59 Other languages 65 Bibliography 73 Estonia Country profile 79 Russian 88 Other languages 99 Bibliography 108 Hungary Country profile 111 Croatian 127 German 132 Romani 138 Romanian 143 Serbian 148 Slovak 152 Slovenian 156 Other languages 160 Bibliography 164 i Latvia Country profile 167 Belorussian 176 Polish 180 Russian 184 Ukrainian 189 Other languages 193 Bibliography 198 Lithuania Country profile 200 Polish 207 Russian 212 Other languages 217 Bibliography 225 Malta Country profile and linguistic situation 227 Poland Country profile 237 Belorussian 244 German 248 Kashubian 255 Lithuanian 261 Ruthenian/Lemkish 264 Ukrainian 268 Other languages 273 Bibliography 277 Slovakia Country profile 278 German 285 Hungarian 290 Romani 298 Other languages 305 Bibliography 313 Slovenia Country profile 316 Hungarian 323 Italian 328 Romani 334 Other languages 337 Bibliography 339 ii PREFACE i The European Union has been called the “modern Babel”, a statement that bears witness to the multitude of languages and cultures whose number has remarkably increased after the enlargement of the Union in May of 2004. -

E.XTENSIONS of REMARKS an APPEAL to CONGRESSIONAL Gion to the Individuals That Are Affected Requested That I Convey Their Message to CONSCIENCE by It

15342 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS June 18, 1979 By Mr. MARKEY: H.R. 4156: Mr. SHELBY. AMENDMENTS H.R. 4522. A blll !or the relief of Annette H.R. 4157: Mr. COELHO, Mr. LAGOMARSINO, Jutta Wohrle; to the Committee on the Mr. PANETTA, and Mr. LUNGREN. Under clause 6 of rule XXIII, pro Judiciary. H.R. 4158: Mr. MITCHELL of Maryland, Mr. posed amendments were submitted as By Mr. QUILLEN: SYMMS, Mr. GRISHAM, Mr. WHITEHURST, Mr. follows: HoLLAND, Mr. WINN, Mr. McKINNEY, Mr. NEAL, H.R. 4057 H.R. 4523. A bill directing the President to Mr. BAFALIS, Mr. EDWARDS Of California, Mr. By Mr. KELLY: award a medal of honor to Jordan M. Robin FRENZEL, Mr. LAGOMARSINO, Mr. AMBRO, Mr. son; to the Committee on Armed Services. -on page 1, line 8, Insert the following new MINETA, Mr. CHAPPELL, Mr. DoRNAN, Mr. ED section 3: GAR, Mr. BURGENER, Mr. WEISS, Mr. McHUGH, SEc. 3. Section 5(e) of the Food Stamp Act Mr. AKAKA, Mr. HoPKINS, and Mr. CoURTER. of 1977 is amended by inserting the following ADDITIONAL SPONSORS H.R. 4443: Mr. SOLARZ, Mr. MURPHY of new sentence: "Any individual 1s entitled to Pennsylvania, and Mr. STGERMAIN. claim a deduction from his household in Under clause 4 of rule XXII, sponsors H. Oon. Res. 59: Mr. CHENEY. to come, above the standard deduction, !or his were added public bills and resolu H. Con. Res. 1:l4: lvLr. n.N.LJ.E.R.::ION of Illinois, medical and dental expenses, to the extent tions as follows: Mr. ANTHONY, Mr. BADHAM, Mr. -

DX Times Master Page Copy

N.Z. RADIO New Zealand DX Times N.Z. RADIO Monthly journal of the D X New Zealand Radio DX League (est. 1948) D X July 2004 - Volume 56 Number 9 LEAGUE http://radiodx.com LEAGUE Contribution deadline for next issue is Wed 4th August 2004 PO Box 3011, Auckland CONTENTS FRONT COVER REGULAR COLUMNS Bandwatch Under 9 3 An Advertisement from ‘The New Zealand with Ken Baird Radio Times’ 1936 Bandwatch Over 9 8 with Stuart Forsyth Fcst SW Reception 12 Compiled by Mike Butler English in Time Order 13 Shortwave Bandwatch Over 9 with Yuri Muzyka A reminder that Stuart Forsyth is now doing the Shortwave Mailbag 15 Bandwatch Over 9 and you can send your notes with Laurie Boyer to Stuart at Shortwave Report 15 with Ian Cattermole’ c/- NZRDXL, P.O.Box 3011, Auckland Utilities 21 with Evan Murray or direct to TV/FM 23 27 Mathias Street with Adam Claydon Darfield 8172 Broadcast news/DX 32 with Tony King E-mail: US X Band List 37 [email protected] Compiled by Tony King or ADCOM News 41 [email protected] with Bryan Clark Branch News 43 with Chief Editor Coming up in next Month’s Magazine OTHER August League Subscription 25 Form Remember to update your Ladder totals Questionnaire 26 Stuart Forsyth MarketSquare 36 c/- NZRDXL, P.O.Box 3011, Auckland Waianakarua Winter 38 or direct to Solstice Trail Stuart Forsyth by Paul Ormandy 27 Mathias Street Random Thoughts- 43 Darfield 8172 Let's dump 'DX' and E-mail: [email protected] kill the 'QSL' from our vocabulary by David Ricquish League Subscription Form and Questionnaire Page 25/26 Please remember to pay your subscription if it is due and also fill out the questionnaire. -

Annual Report, Yerevan, 2011, 117 Pages

The Office of Financial System Mediator Annual Report, Yerevan, 2011, 117 pages This book presents the Annual Report of the Office of Financial System Mediator of the Republic of Armenia. The book is compiled and published for the Office of Fi- nancial System Mediator and is not for sale. Design by Lilit Harutyunyan | DEEM PRODUCTIONS Yerevan, Armenia Dear reader, This is the second year now that the Office of Finan- cial System Mediator has been functioning in the Republic of Armenia. We have spent much effort to earn more recognition and trust of households and financial organizations. Not only was the second year remarkable with an increased number of complaints lodged but also with projects that the Office launched to educate people on financial products. The Office continues its activities consistent with international developments, and in the period under review we kept focus on the cooperation with our foreign coun- terparts in order to exchange experience and intro- duce best international practice to the Office. The Office remains committed to enhancing partner- ship with financial organizations as it held a number of roundtable discussions, in addition to the confer- ence with an involvement of representatives of finan- cial organizations, to address specific issues and find ways on how these could be overcome. We may state that the Office tracked success in its second year of activities for earning recognition and trust –an increasing amount of clients having come up to the Office even in its passive period of elucidatory activities is quite a case in point. This is very impor- tant in a sense that more complaints are expected to come from citizens hence users of financial services – as a result of introduction of the compulsory insur- ance against civil liability in respect of the use of mo- tor vehicles and the private pension scheme. -

The Armenian Ombudsman Was Elect - INDEX Second Annual Convention Ed a Member of the Association at the Armenia

JULY 24, 2010 MirTHE rARoMENr IAN -Spe ctator Volume LXXXI, NO. 2, Issue 414 6 $ 2.00 NEWS IN BRIEF The First English Language Armenian Weekly in the United States Turkish FM Says No Breakthrough Border with Armenia In Karabagh Talks Will Not Open ANAKRA (ArmRadio) — Turkish Foreign Minister Reported Ahmet Davutoglu has dismissed prospects of open - ing the Turkish-Armenian border in the foreseeable ALMATY, Kazakhstan (RFE/RL) — The future, saying reports to that effect in the media foreign ministers of Armenia and were not accurate. Azerbaijan appear to have failed to make “There is no such thing as the opening of the bor - any progress during two days of fresh nego - der. It is not on the government’s agenda and reports tiations in Kazakhstan which international to that effect are wrong,” Davutoglu told reporters mediators hoped would bring them closer on the sidelines of an Organization for Security and to the resolution of the Nagorno-Karabagh Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) meeting. conflict. Eduard Nalbandian and Elmar Mammadyarov began the talks late Friday Armenia and Russia to on the margins of an informal Organization Boost Military Ties for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) ministerial meeting in the Kazakh YEREVAN (Arka) — Armenia and Russia reached city of Almaty. They met again on Saturday concrete agreements to boost their cooperation in in the presence of Russian Foreign Minister Edele Hovnanian and Siran Sahakian cut the ribbon while President Serge Sargisian, military-industrial sector embracing five directions, Catholicos of All Armenians Karekin II and Hirair Hovnanian look on. Sergei Lavrov, French Foreign Minister chief of Armenian National Security Council Bernard Kouchner and US Deputy Arthur Baghdasarian said this week. -

COMPLETE DRAFT Copy Copy

Peace and Security beyond Military Power: The League of Nations and the Polish-Lithuanian Dispute (1920-1923) Chiara Tessaris Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Chiara Tessaris All rights reserved ABSTRACT Peace and Security beyond Military Power: The League of Nations and the Polish- Lithuanian Dispute Chiara Tessaris Based on the case study of the mediation of the Polish-Lithuanian dispute from 1920 to 1923, this dissertation explores the League of Nations’ emergence as an agency of modern territorial and ethnic conflict resolution. It argues that in many respects, this organization departed from prewar traditional diplomacy to establish a new, broader concept of security. At first the league tried simply to contain the Polish-Lithuanian conflict by appointing a Military Commission to assist these nations in fixing a final border. But the occupation of Vilna by Polish troops in October 1920 exacerbated Polish-Lithuanian relations, turning the initial border dispute into an ideological conflict over the ethnically mixed region of Vilna, claimed by the Poles on ethnic grounds while the Lithuanians considered it the historical capital of the modern Lithuanian state. The occupation spurred the league to greater involvement via administration of a plebiscite to decide the fate of the disputed territories. When this strategy failed, Geneva resorted to negotiating the so-called Hymans Plan, which aimed to create a Lithuanian federal state and establish political and economic cooperation between Poland and Lithuania. This analysis of the league’s mediation of this dispute walks the reader through the league’s organization of the first international peacekeeping operation, its handling of the challenges of open diplomacy, and its efforts to fulfill its ambitious mandate not just to prevent war but also to uproot its socioeconomic and ethnic causes. -

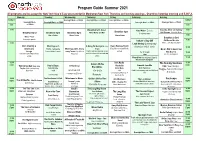

Program Guide Summer 2021

Program Guide Summer 2021 All programs are live except for New York Nice’n’Easy pre-recorded in Manhattan New York Thursday and Sunday evenings , Overdrive Saturday morning and B.O.F.A. Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday 12.00am Overnight Music or CBAA Overnight Music or CBAA Overnight Music or CBAA 12.00am Overnight Music Overnight Music or CBAA Overnight Music or CBAA Overnight Music or CBAA 1:00 on CBAA 1:00 6:00 6:00 Breakfast with Baker Kate Weber Eclectic Sounds Alive on Sunday Breakfast Spot Neil Cranmer---Christian Music Breakfast Spot Breakfast Spot Breakfast Spot Simon Baker and Mel Contemporary Bruce Potter Bruce Potter Bruce Potter 7:00 Bruce Potter Breakfast in Bed Comedy/requests Saturn’s Day Off Phil Rosen Mic-side 8:00 9:00 Leah Veritay Contemporary/ Music, contemporary adult Ray’s Rumpus Room GG’s Country & Mornings with A Song for Everyone John Alternative /Indie/French 10:00 Americana Harry, Ledowsky Mornings with Jenny Regan Ray Shoostovian Rock Mick’s Old School Cool Adult Contemporary pop & soul Georgie Current affairs & music Jenny Tucker Pop & Rock n Roll To 11.30 AM Mick Drayson 11:00 and interviews with international interviews with international Requests then Rock’ n’ Roll &blues artists artists Overdrive Motoring/music David 11:30 Brown/ David Campbell 12:00 Irish Radio 12.00 Golden Oldies The Sunday Sessions noon Pete’s Beats Australia Smooth Jazz Mix noon Well Grounded Mary Jane In Harmony Ron Atkins R&B, Soul, Gospel, Trujillo Adult contemporary Peter Brichta Barry Mack Nick Hammond Reggae, feat. -

CD-Rezensionen (PDF)

58 CD-REZENSIONEN damalige Gitarrist fanden sich letztendlich Gärtner und Daniel Schild. Mal mit akusti- es allesamt zu Stadienhymnen bringen könn- aber zusammen, um eine neue Band zu scher Gitarre, mal mit E-Gitarre oder dem ten. Das Trio Logan, Hornung und Thiele gründen. Es dauerte nicht lange, bis Bassist Piano: Philip Bölter weiß, wie er für die nöti- bedient inzwischen immer erfolgreicher Egbert Rosner zur Band stieß. 1999 war ge Abwechslung in seinen Songs sorgt. Für Guinness trinkende Konzertgänger mit dann mit Sebastian Bibow ein geeigneter Liebhaber von eher anspruchsvoller seinem Popfolkclassicrock. Unterstrichen Sänger gefunden, der aber nach zehn Jahren Musik ein schöner Silberling. haben sie ihre Ambitionen erfolgreich beim EWANE MUSIC aus privaten Gründen ausstieg. Daniel http://philip-boelter.de A.J.-D. Deutschen Rock & Pop Preis 2011, wo »New Soul« Riedel war ein würdiger Ersatz und nach sie die Kategorien „Beste Folkrockband“, vier Gitarristenwechseln wurde Markus „Bester Folkrocksong“ und „Beste Single“ Ewane Makia wurde 1988 in Kumba/ Buchholz zum festen Mitglied. HERTZSCHLAG gewannen. ACOUSTIC REVOLUTION kreier- Kamerun geboren. Seine Mutter verstarb belegten 2007 den zweiten Platz beim 25. ten ihren eigenen Sound, der sich mit Right leider bei der Geburt und sein leiblicher Deutschen Rock & Pop Preis in der Kate - Said Fred meets Levellers kurz umschrei- Vater war so überfordert mit seiner Vater - gorie „Hard’n’Heavy“ und standen unter ben ließe. Im Sinne von „Gimme More“, rolle, dass seine Tante die Erziehung über- anderem bereits mit ihren Genre-Kollegen einem weiteren Stimmungshöhepunkt, wer- nahm. Ein wichtige Rolle in seinem Leben Stahlhammer auf der Bühne. Wer den den wir sicher noch mehr von dieser akusti- spielt der deutsche Tropenarzt Dr. -

Why Armenia's Future Is in Europe

#ElectricYerevan: Why Armenia’s Future is in Europe © 2015 IAI by Nona Mikhelidze ABSTRACT Armenia’s electricity price hike and more broadly its deteriorating economic circumstances have triggered mass ISSN 2280-4341 | ISBN 978-88-98650-46-0 protests in Yerevan. But there is more to “Electric Armenia” than economics. Because of the security concerns related to the unresolved Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, Yerevan was forced into a military alliance with Russia. Moscow did not limit this alliance to security issues, but used the alliance to ensure Armenia’s full-fledged political and economic dependence on the Kremlin. In order to accommodate Russian interests, Armenia’s governance style has become increasingly top down. This notwithstanding a burgeoning civil society, which is mature enough to stand up in defence of democratic values. New forms of active citizenship are emerging in Armenia, as youth movements raise their voice in Baghramyan Avenue. The current demonstrations may not cause a breakthrough and immediate U-turn in Armenia’s domestic and foreign policy priorities, but a value system clash between Armenia and Russia is in the making, exacerbating the ongoing clash in EU-Russia relations. Armenia | Civil society | Democracy | Energy | Russia | European Union keywords IAI WORKING PAPERS 15 | 22 - JULY 2015 15 | 22 - JULY IAI WORKING PAPERS #ElectricYerevan: Why Armenia’s Future is in Europe #ElectricYerevan: Why Armenia’s Future is in Europe by Nona Mikhelidze* © 2015 IAI Introduction “Free and independent Armenia. We are the decision makers.” With this slogan and a demand to reverse the latest decision to increase electricity prices, thousands of Armenians (mostly youth) are protesting in the capital city of Yerevan. -

Lilya Arakelyan

LILIA ARAKELYAN Miami, Florida [email protected] EDUCATION Doctor of Philosophy, International Studies, December 2015 University of Miami, Coral Gables, Florida Dissertation: “The Eurasian Union: Do Not Count Your Member States Before They Are Hatched.” Dissertation Faculty Advisor: Professor Roger E. Kanet Master of Arts, Russian and Slavic Studies, May 2009 University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona Thesis: “Armenian Immigration to the United States after the Fall of the Soviet Union: New Trends and Developments.” Thesis Faculty Advisor: Professor George Gutsche Bachelor of Science, Russian Language and Literature, June 1997 Yerevan State University, Yerevan, Armenia Thesis: “Analysis of the Political and Social-Economical Editorials of One of the Most Influential National Russian Daily Newspapers Izvestia.” Thesis Faculty Advisor: Professor Levon Kirakosyan PUBLICATIONS Books Russian Foreign Policy in Eurasia: National Interests and Regional Integration. Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 2017. Chapters in Books “Caucasian Chess or The Greatest Geopolitical Tragedy of the 20th century,” in Roger E. Kanet, ed., Routledge Handbook of Russian Security. Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 2019. “EU-Russia Security Relations: Another Kind of Europe,” in Roger E. Kanet, ed., Challenges to the Security Environment in Eurasia. Houndmills, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017. “Quo Vadis Armenia? The South Caucasus and Great Power Politics,” in Roger E. Kanet and Matthew Sussex, eds., Russia, Eurasia, and the New Geopolitics of Energy. Houndmills, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015. “The Soviet Union is Dead: Long Live the Eurasian Union!” in Roger E. Kanet and Rémi Piet, eds., Shifting Priorities in Russia’s Foreign and Security Policy. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate Publishing, 2014. Arakelyan-Page 2 “Russian Energy Policy in the South Caucasus,” (with Roger E.