The Balfour Declaration, November 1917

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inventory of the William A. Rosenthall Judaica Collection, 1493-2002

Inventory of the William A. Rosenthall Judaica collection, 1493-2002 Addlestone Library, Special Collections College of Charleston 66 George Street Charleston, SC 29424 USA http://archives.library.cofc.edu Phone: (843) 953-8016 | Fax: (843) 953-6319 Table of Contents Descriptive Summary................................................................................................................ 3 Biographical and Historical Note...............................................................................................3 Collection Overview...................................................................................................................4 Restrictions................................................................................................................................ 5 Search Terms............................................................................................................................6 Related Material........................................................................................................................ 5 Separated Material.................................................................................................................... 5 Administrative Information......................................................................................................... 7 Detailed Description of the Collection.......................................................................................8 Postcards.......................................................................................................................... -

The Night Operation on the Passchendaele Ridge, 2Nd December 1917

Centre for First World War Studies A Moonlight Massacre: The Night Operation on the Passchendaele Ridge, 2nd December 1917 by Michael Stephen LoCicero Thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of History and Cultures College of Arts & Law June 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract The Third Battle of Ypres was officially terminated by Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig with the opening of the Battle of Cambrai on 20 November 1917. Nevertheless, a comparatively unknown set-piece attack – the only large-scale night operation carried out on the Flanders front during the campaign – was launched twelve days later on 2 December. This thesis, a necessary corrective to published campaign narratives of what has become popularly known as „Passchendaele‟, examines the course of events from the mid-November decision to sanction further offensive activity in the vicinity of Passchendaele village to the barren operational outcome that forced British GHQ to halt the attack within ten hours of Zero. A litany of unfortunate decisions and circumstances contributed to the profitless result. -

Jewish Encyclopedia

Jewish Encyclopedia The History, Religion, Literature, And Customs Of The Jewish People From The Earliest Times To The Present Day Volume XII TALMUD – ZWEIFEL New York and London FUNK AND WAGNALLS COMPANY MDCCCCVI ZIONISM: Movement looking toward the segregation of the Jewish people upon a national basis and in a particular home of its own: specifically, the modern form of the movement that seeks for the Jews “a publicly and legally assured home in Palestine,” as initiated by Theodor Herzl in 1896, and since then dominating Jewish history. It seems that the designation, to distinguish the movement from the activity of the Chovevei Zion, was first used by Matthias Acher (Birnbaum) in his paper “Selbstemancipation,” 1886 (see “Ost und West,” 1902, p. 576: Ahad ha – ‘Am, “Al Parashat Derakim,” p. 93, Berlin, 1903). Biblical Basis The idea of a return of the Jews to Palestine has its roots in many passages of Holy Writ. It is an integral part of the doctrine that deals with the Messianic time, as is seen in the constantly recurring expression, “shub shebut” or heshib shebut,” used both of Israel and of Judah (Jer. xxx, 7,1; Ezek. Xxxix. 24; Lam. Ii. 14; Hos. Vi. 11; Joel iv. 1 et al.). The Dispersion was deemed merely temporal: ‘The days come … that … I will bring again the captivity of my people of Israel, and they shall build the waste cities and inhabit them; and they shall plant vineyards, and drink the wine thereof … and I will plant them upon their land, and they shall no more be pulled up out of their land” (Amos ix. -

Forming a Nucleus for the Jewish State

Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................... 3 Jewish Settlements 70 CE - 1882 ......................................................... 4 Forming a Nucleus for First Aliyah (1882-1903) ...................................................................... 5 Second Aliyah (1904-1914) .................................................................. 7 the Jewish State: Third Aliyah (1919-1923) ..................................................................... 9 First and Second Aliyot (1882-1914) ................................................ 11 First, Second, and Third Aliyot (1882-1923) ................................... 12 1882-1947 Fourth Aliyah (1924-1929) ................................................................ 13 Fifth Aliyah Phase I (1929-1936) ...................................................... 15 First to Fourth Aliyot (1882-1929) .................................................... 17 Dr. Kenneth W. Stein First to Fifth Aliyot Phase I (1882-1936) .......................................... 18 The Peel Partition Plan (1937) ........................................................... 19 Tower and Stockade Settlements (1936-1939) ................................. 21 The Second World War (1940-1945) ................................................ 23 Postwar (1946-1947) ........................................................................... 25 11 Settlements of October 5-6 (1947) ............................................... 27 First -

Arab-Israeli Relations

FACTSHEET Arab-Israeli Relations Sykes-Picot Partition Plan Settlements November 1917 June 1967 1993 - 2000 May 1916 November 1947 1967 - onwards Balfour 1967 War Oslo Accords which to supervise the Suez Canal; at the turn of The Balfour Declaration the 20th century, 80% of the Canal’s shipping be- Prepared by Anna Siodlak, Research Associate longed to the Empire. Britain also believed that they would gain a strategic foothold by establishing a The Balfour Declaration (2 November 1917) was strong Jewish community in Palestine. As occupier, a statement of support by the British Government, British forces could monitor security in Egypt and approved by the War Cabinet, for the establish- protect its colonial and economic interests. ment of a national home for the Jewish people in Palestine. At the time, the region was part of Otto- Economics: Britain anticipated that by encouraging man Syria administered from Damascus. While the communities of European Jews (who were familiar Declaration stated that the civil and religious rights with capitalism and civil organisation) to immigrate of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine to Palestine, entrepreneurialism and development must not be deprived, it triggered a series of events would flourish, creating economic rewards for Brit- 2 that would result in the establishment of the State of ain. Israel forcing thousands of Palestinians to flee their Politics: Britain believed that the establishment of homes. a national home for the Jewish people would foster Who initiated the declaration? sentiments of prestige, respect and gratitude, in- crease its soft power, and reconfirm its place in the The Balfour Declaration was a letter from British post war international order.3 It was also hoped that Foreign Secretary Lord Arthur James Balfour on Russian-Jewish communities would become agents behalf of the British government to Lord Walter of British propaganda and persuade the tsarist gov- Rothschild, a prominent member of the Jewish ernment to support the Allies against Germany. -

American Armies and Battlefields in Europe

Chapter v1 THE AMERICAN BATTLEFIELDS NORTH OF PARIS chapter gives brief accounts of areas and to all of the American ceme- all American fighting whi ch oc- teries and monuments. This route is Thiscurred on the battle front north of recommended for those who desire to Paris and complete information concern- make an extended automobile tour in the ing the American military cemeteries and region. Starting from Paris, it can be monuments in that general region. The completely covered in four days, allowing military operations which are treated are plenty of time to stop on the way. those of the American lst, 27th, 30th, The accounts of the different operations 33d, 37th, 80th and 91st Divisions and and the descriptions of the American the 6th and 11 th Engineer Regiments. cemeteries and monuments are given in Because of the great distances apart of the order they are reached when following So uthern Encr ance to cb e St. Quentin Can al Tunnel, Near Bellicourc, October 1, 1918 the areas where this fighting occurred no the suggested route. For tbis reason they itinerary is given. Every operation is do not appear in chronological order. described, however, by a brief account Many American units otber tban those illustrated by a sketch. The account and mentioned in this chapter, sucb as avia- sketch together give sufficient information tion, tank, medical, engineer and infantry, to enable the tourist to plan a trip through served behind this part of the front. Their any particular American combat area. services have not been recorded, however, The general map on the next page as the space limitations of tbis chapter indicates a route wbich takes the tourist required that it be limited to those Amer- either int o or cl ose to all of tbese combat ican organizations which actually engaged (371) 372 THE AMERICAN B ATTLEFIELD S NO R TH O F PARIS Suggested Tour of American Battlefields North of Paris __ Miles Ghent ( î 37th and 91st Divisions, Ypres-Lys '"offensive, October 30-November 11, 1918 \ ( N \ 1 80th Division, Somme 1918 Albert 33d Division. -

Revolution in Real Time: the Russian Provisional Government, 1917

ODUMUNC 2020 Crisis Brief Revolution in Real Time: The Russian Provisional Government, 1917 ODU Model United Nations Society Introduction seventy-four years later. The legacy of the Russian Revolution continues to be keenly felt The Russian Revolution began on 8 March 1917 to this day. with a series of public protests in Petrograd, then the Winter Capital of Russia. These protests But could it have gone differently? Historians lasted for eight days and eventually resulted in emphasize the contingency of events. Although the collapse of the Russian monarchy, the rule of history often seems inventible afterwards, it Tsar Nicholas II. The number of killed and always was anything but certain. Changes in injured in clashes with the police and policy choices, in the outcome of events, government troops in the initial uprising in different players and different accidents, lead to Petrograd is estimated around 1,300 people. surprising outcomes. Something like the Russian Revolution was extremely likely in 1917—the The collapse of the Romanov dynasty ushered a Romanov Dynasty was unable to cope with the tumultuous and violent series of events, enormous stresses facing the country—but the culminating in the Bolshevik Party’s seizure of revolution itself could have ended very control in November 1917 and creation of the differently. Soviet Union. The revolution saw some of the most dramatic and dangerous political events the Major questions surround the Provisional world has ever known. It would affect much Government that struggled to manage the chaos more than Russia and the ethnic republics Russia after the Tsar’s abdication. -

Jan Smuts, Howard University, and African American Leandership, 1930 Robert Edgar

Ouachita Baptist University Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita Articles Faculty Publications 12-15-2016 "The oM st Patient of Animals, Next to the Ass:" Jan Smuts, Howard University, and African American Leandership, 1930 Robert Edgar Myra Ann Howser Ouachita Baptist University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/articles Part of the African History Commons, Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Edgar, Robert and Howser, Myra Ann, ""The osM t Patient of Animals, Next to the Ass:" Jan Smuts, Howard University, and African American Leandership, 1930" (2016). Articles. 87. https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/articles/87 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “The Most Patient of Animals, Next to the Ass:” Jan Smuts, Howard University, and African American Leadership, 1930 Abstract: Former South African Prime Minister Jan Smuts’ 1930 European and North American tour included a series of interactions with diasporic African and African American activists and intelligentsia. Among Smuts’s many remarks stands a particular speech he delivered in New York City, when he called Africans “the most patient of all animals, next to the ass.” Naturally, this and other comments touched off a firestorm of controversy surrounding Smuts, his visit, and segregationist South Africa’s laws. Utilizing news coverage, correspondence, and recollections of the trip, this article uses his visit as a lens into both African American relations with Africa and white American foundation work towards the continent and, especially, South Africa. -

The Gordian Knot: Apartheid & the Unmaking of the Liberal World Order, 1960-1970

THE GORDIAN KNOT: APARTHEID & THE UNMAKING OF THE LIBERAL WORLD ORDER, 1960-1970 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Ryan Irwin, B.A., M.A. History ***** The Ohio State University 2010 Dissertation Committee: Professor Peter Hahn Professor Robert McMahon Professor Kevin Boyle Professor Martha van Wyk © 2010 by Ryan Irwin All rights reserved. ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the apartheid debate from an international perspective. Positioned at the methodological intersection of intellectual and diplomatic history, it examines how, where, and why African nationalists, Afrikaner nationalists, and American liberals contested South Africa’s place in the global community in the 1960s. It uses this fight to explore the contradictions of international politics in the decade after second-wave decolonization. The apartheid debate was never at the center of global affairs in this period, but it rallied international opinions in ways that attached particular meanings to concepts of development, order, justice, and freedom. As such, the debate about South Africa provides a microcosm of the larger postcolonial moment, exposing the deep-seated differences between politicians and policymakers in the First and Third Worlds, as well as the paradoxical nature of change in the late twentieth century. This dissertation tells three interlocking stories. First, it charts the rise and fall of African nationalism. For a brief yet important moment in the early and mid-1960s, African nationalists felt genuinely that they could remake global norms in Africa’s image and abolish the ideology of white supremacy through U.N. -

JABOTINSKY on CANADA and the Unlted STATES*

A CASE OFLIMITED VISION: JABOTINSKY ON CANADA AND THE UNlTED STATES* From its inception in 1897, and even earlier in its period of gestation, Zionism has been extremely popular in Canada. Adherence to the movement seemed all but universal among Canada's Jews by the World War I era. Even in the interwar period, as the flush of first achievement wore off and as the Canadian Jewish community became more acclimated, the movement in Canada functioned at a near-fever pitch. During the twenties and thirties funds were raised, acculturatedJews adhered toZionism with some settling in Palestine, and prominent gentile politicians publicly supported the movement. The contrast with the United States was striking. There, Zionism got a very slow start. At the outbreak of World War I only one American Jew in three hundred belonged to the Zionist movement; and, unlike Canada, a very strong undercurrent of anti-Zionism emerged in the Jewish community and among gentiles. The conversion to Zionism of Louis D. Brandeis-prominent lawyer and the first Jew to sit on the United States Supreme Court-the proclamation of the Balfour Declaration, and the conquest of Palestine by the British gave Zionism in the United States a significant boost during the war. Afterwards, however, American Zionism, like the country itself, returned to "normalcy." Membership in the movement plummeted; fundraising languished; potential settlers for Palestine were not to be found. One of the chief impediments to Zionism in America had to do with the nature of the relationship of American Jews to their country. Zionism was predicated on the proposition that Jews were doomed to .( 2 Michuel Brown be aliens in every country but their own. -

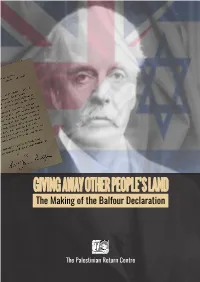

The Making of the Balfour Declaration

The Making of the Balfour Declaration The Palestinian Return Centre i The Palestinian Return Centre is an independent consultancy focusing on the historical, political and legal aspects of the Palestinian Refugees. The organization offers expert advice to various actors and agencies on the question of Palestinian Refugees within the context of the Nakba - the catastrophe following the forced displacement of Palestinians in 1948 - and serves as an information repository on other related aspects of the Palestine question and the Arab-Israeli conflict. It specializes in the research, analysis, and monitor of issues pertaining to the dispersed Palestinians and their internationally recognized legal right to return. Giving Away Other People’s Land: The Making of the Balfour Declaration Editors: Sameh Habeeb and Pietro Stefanini Research: Hannah Bowler Design and Layout: Omar Kachouch All rights reserved ISBN 978 1 901924 07 7 Copyright © Palestinian Return Centre 2017 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publishers or author, except in the case of a reviewer, who may quote brief passages embodied in critical articles or in a review. مركز العودة الفلسطيني PALESTINIAN RETURN CENTRE 100H Crown House North Circular Road, London NW10 7PN United Kingdom t: 0044 (0) 2084530919 f: 0044 (0) 2084530994 e: [email protected],uk www.prc.org.uk ii Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................3 -

1 the Wilson-Smuts Synthesis: Racial Self

The Wilson-Smuts Synthesis: Racial Self-Determination and the Institutionalization of World Order A thesis submitted by Scott L. Malcomson in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in International Relations Tufts University Fletcher School of International Law and Diplomacy January 2020 Adviser: Jeffrey W. Taliaferro ©2019, Scott L. Malcomson 1 Table of Contents I: Introduction 3 II: Two Paths to Paris. Jan Smuts 8 Woodrow Wilson 26 The Paths Converge 37 III: Versailles. Wilson Stays Out: Isolation and Neutrality 43 Lloyd George: Bringing the Empire on Board 50 Smuts Goes In: The Rise of the Dominions 54 The Wilson-Smuts Synthesis 65 Wilson Undone 72 The Racial Equality Bill 84 IV: Conclusion 103 Bibliography 116 2 I: Introduction When President Woodrow Wilson left the United States for Europe at the end of 1918, he intended to create a new structure for international relations, based on a League of Nations, that would replace the pre-existing imperialist world structure with one based on national and racial (as was said at the time) self-determination. The results Wilson achieved by late April 1919, after several months of near-daily negotiation in Paris, varied between partial success and complete failure.1 Wilson had had other important goals in Paris, including establishing a framework for international arbitration of disputes, advancing labor rights, and promoting free trade and disarmament, and progress was made on all of these. But in terms of his own biography and the distinctive mission of U.S. foreign policy as he and other Americans understood it, the anti- imperial and pro-self-determination goals were paramount.