Diploid and Polyploid Cytotype Distribution in Melampodium Cinereum and M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SALT TOLERANT PLANTS Recommended for Pender County Landscapes

North Carolina Cooperative Extension NC STATE UNIVERSITY SALT TOLERANT PLANTS Recommended for Pender County Landscapes Pender County Cooperative Extension Urban Horticulture Leaflet 14 Coastal Challenges Plants growing at the beach are subjected to environmental conditions much different than those planted further inland. Factors such as blowing sand, poor soils, high temperatures, and excessive drainage all influence how well plants perform in coastal landscapes, though the most significant effect on growth is salt spray. Most plants will not tolerate salt accumulating on their foliage, making plant selection for beachfront land- scapes particularly challenging. Salt Spray Salt spray is created when waves break on the beach, throwing tiny droplets of salty water into the air. On-shore breezes blow this salt laden air landward where it comes in contact with plant foliage. The amount of salt spray plants receive varies depending on their proximity to the beachfront, creating different vegetation zones as one gets further away from the beachfront. The most salt-tolerant species surviving in the frontal dune area. As distance away from the ocean increases, the level of salt spray decreases, allowing plants with less salt tolerance to survive. Natural Protection The impact of salt spray on plants can be lessened by physically blocking salt laden winds. This occurs naturally in the maritime forest, where beachfront plants protect landward species by creating a layer of foliage that blocks salt spray. It is easy to see this effect on the ocean side of maritime forest plants, which are “sheared” by salt spray, causing them to grow at a slant away from the oceanfront. -

© 2020 Theodore Payne Foundation for Wild Flowers & Native Plants. No

May 8, 2020 Theodore Payne Foundation’s Wild Flower Hotline is made possible by donations, memberships and sponsors. You can support TPF by shopping the online gift store as well. A new, pay by phone, contactless plant pickup system is now available. Details here. Widespread closures remain in place. If you find an accessible trail, please practice social distancing. The purpose for the Wild Flower Hotline now is NOT to send you to localities for wild flower viewing, but to post photos that assure you—virtually—that California’s wild spaces are still open for business for flowers and their pollinators. LA County’s Wildlife Sanctuaries are starting to dry up from the heat. This may be the last week to see flowers at Jackrabbit Flats and Theodore Payne Wildlife Sanctuaries near Littlerock in the high desert. Yellow is the dominant color with some pink and white scattered about. Parry’s linanthus (Linanthus parryae) and Bigelow’s coreopsis (Leptosyne bigelovii), are widespread. Small patches of goldfields (Lasthenia californica), and Mojave sun cups (Camissonia campestris) are still around. If you are visiting around dusk, the evening snow (Linanthus dichotomus) open up and put on a display that lives up to its name. Strewn around are Pringle’s woolly sunflower (Eriophyllum pringlei), white tidy tips (Layia glandulosa), owl’s clover (Castilleja sp.) and desert dandelion (Malacothrix glabrata). Underneath the creosote bushes, lacy phacelia (Phacelia tanacetifolia) is seeking out some shade. Theodore Payne Sanctuary has all these flowers, and because it has more patches of sandy alluvial soils, has some cute little belly flowers like Wallace’s wooly daisy (Eriophyllum wallacei) and purple mat (Nama demissa) too. -

Multiple Pleistocene Refugia and Holocene Range Expansion of an Abundant Southwestern American Desert Plant Species (Melampodium Leucanthum, Asteraceae)

Molecular Ecology (2010) 19, 3421–3443 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04754.x Multiple Pleistocene refugia and Holocene range expansion of an abundant southwestern American desert plant species (Melampodium leucanthum, Asteraceae) CAROLIN A. REBERNIG,* GERALD M. SCHNEEWEISS,†1 KATHARINA E. BARDY,†* PETER SCHO¨ NSWETTER,†‡ JOSE L. VILLASEN˜ OR,– RENATE OBERMAYER,* TOD F. STUESSY* and HANNA WEISS-SCHNEEWEISS* *Department of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany, University of Vienna, Rennweg 14, A-1030 Vienna, Austria; †Department of Biogeography and Botanical Garden, University of Vienna, Rennweg 14, A-1030 Vienna, Austria; ‡Department of Systematics, Palynology and Geobotany, Institute of Botany, University of Innsbruck, Sternwartestrasse 15, A-6020 Innsbruck, Austria; –Instituto de Biologı´a, Departamento de Bota´nica, Universidad Nacional Auto´noma de Me´xico, Tercer Circuito s ⁄ n, Ciudad Universitaria, Delegacio´n Coyoaca´n, MX-04510 Me´xico D. F., Me´xico Abstract Pleistocene climatic fluctuations had major impacts on desert biota in southwestern North America. During cooler and wetter periods, drought-adapted species were isolated into refugia, in contrast to expansion of their ranges during the massive aridification in the Holocene. Here, we use Melampodium leucanthum (Asteraceae), a species of the North American desert and semi-desert regions, to investigate the impact of major aridification in southwestern North America on phylogeography and evolution in a widespread and abundant drought-adapted plant species. The evidence for three separate Pleistocene refugia at different time levels suggests that this species responded to the Quaternary climatic oscillations in a cyclic manner. In the Holocene, once differentiated lineages came into secondary contact and intermixed, but these range expansions did not follow the eastwardly progressing aridification, but instead occurred independently out of separate Pleistocene refugia. -

Outline of Angiosperm Phylogeny

Outline of angiosperm phylogeny: orders, families, and representative genera with emphasis on Oregon native plants Priscilla Spears December 2013 The following listing gives an introduction to the phylogenetic classification of the flowering plants that has emerged in recent decades, and which is based on nucleic acid sequences as well as morphological and developmental data. This listing emphasizes temperate families of the Northern Hemisphere and is meant as an overview with examples of Oregon native plants. It includes many exotic genera that are grown in Oregon as ornamentals plus other plants of interest worldwide. The genera that are Oregon natives are printed in a blue font. Genera that are exotics are shown in black, however genera in blue may also contain non-native species. Names separated by a slash are alternatives or else the nomenclature is in flux. When several genera have the same common name, the names are separated by commas. The order of the family names is from the linear listing of families in the APG III report. For further information, see the references on the last page. Basal Angiosperms (ANITA grade) Amborellales Amborellaceae, sole family, the earliest branch of flowering plants, a shrub native to New Caledonia – Amborella Nymphaeales Hydatellaceae – aquatics from Australasia, previously classified as a grass Cabombaceae (water shield – Brasenia, fanwort – Cabomba) Nymphaeaceae (water lilies – Nymphaea; pond lilies – Nuphar) Austrobaileyales Schisandraceae (wild sarsaparilla, star vine – Schisandra; Japanese -

Plants for Sun & Shade

Plants for Dry Shade Blue Shade Ruellia Ruellia tweediana Bugleweed Ajuga Cast Iron Plant Aspidistra Cedar Sage Salvia roemeriana Columbine Aquilegia Coral Bells Heuchera Flax Lily Dianella tasmanica ‘variegata’ Frog Fruit Phyla nodiflora Heartleaf Skullcap Scutellaria ovata ssp. Bracteata Japanese Aralia Fatsia japonica Katie Ruellia Ruellia tweediana Majestic Sage Salvia guaranitica Red Skullcap Scuttelaria longifolia Tropical or Scarlet Sage Salvia coccinea Turk’s Cap Malvaviscus arboreus var. drummondii Virginia Creeper Parthenocissus quinquefolia Plants for Moist Shade Australian Violet Viola hederacea Carex grass Sedge spp. Cardinal Flower Lobelia cardinalis Chinese Ground Orchid Bletilla striata Creeping Daisy Wedelia trilobata Creeping Jenny Lysimachia nummularia Crinum lily Crinum spp. False Spirea Astilbe spp. Fall Obedient Plant Physostegia virginiana Firespike Odontenema strictum Ferns various botanical names Gingers various botanical names Gulf Coast Penstemon Penstemon tenuis Inland Sea Oats Chasmanthium latifolium Ligularia Ligularia spp. Spikemoss Selaginella kraussiana Toadlily Tricyrtis spp. Turk’s Cap Malvaviscus arboreus var. drummondii Tropical or Scarlet Sage Salvia coccinea Water Celery Oenanthe javanica This and other plant care tip sheets are available at Buchanansplants.com. 01/15/16 Plants for Dry Sun Artemisia Artemisia spp. BiColor Iris Dietes bicolor Black-eyed Susan Rudbeckia spp. Blackfoot Daisy Melampodium leucanthum Blanket Flower Gaillardia spp. Bougainvillea Bougainville Bulbine Bulbine frutescens Butterfly Iris Dietes iridioides (Morea) Copper Canyon Daisy Tagetes lemmonii Coral Vine Antigonon leptopus Crossvine Bignonia capreolata Coreopsis Coreopsis spp. Dianella Dianella spp. Four Nerve Daisy Tetraneuris scaposa (Hymenoxys) Gulf Coast Muhly Muhlenbergia capillaris Ice Plant Drosanthemum sp. Mexican Hat Ratibida columnaris Plumbago Plumbago auriculata Rock Rose Pavonia spp. Sedum Sedum spp. Salvias Salvia spp. -

Chromosome Numbers in Compositae, XII: Heliantheae

SMITHSONIAN CONTRIBUTIONS TO BOTANY 0 NCTMBER 52 Chromosome Numbers in Compositae, XII: Heliantheae Harold Robinson, A. Michael Powell, Robert M. King, andJames F. Weedin SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION PRESS City of Washington 1981 ABSTRACT Robinson, Harold, A. Michael Powell, Robert M. King, and James F. Weedin. Chromosome Numbers in Compositae, XII: Heliantheae. Smithsonian Contri- butions to Botany, number 52, 28 pages, 3 tables, 1981.-Chromosome reports are provided for 145 populations, including first reports for 33 species and three genera, Garcilassa, Riencourtia, and Helianthopsis. Chromosome numbers are arranged according to Robinson’s recently broadened concept of the Heliantheae, with citations for 212 of the ca. 265 genera and 32 of the 35 subtribes. Diverse elements, including the Ambrosieae, typical Heliantheae, most Helenieae, the Tegeteae, and genera such as Arnica from the Senecioneae, are seen to share a specialized cytological history involving polyploid ancestry. The authors disagree with one another regarding the point at which such polyploidy occurred and on whether subtribes lacking higher numbers, such as the Galinsoginae, share the polyploid ancestry. Numerous examples of aneuploid decrease, secondary polyploidy, and some secondary aneuploid decreases are cited. The Marshalliinae are considered remote from other subtribes and close to the Inuleae. Evidence from related tribes favors an ultimate base of X = 10 for the Heliantheae and at least the subfamily As teroideae. OFFICIALPUBLICATION DATE is handstamped in a limited number of initial copies and is recorded in the Institution’s annual report, Smithsonian Year. SERIESCOVER DESIGN: Leaf clearing from the katsura tree Cercidiphyllumjaponicum Siebold and Zuccarini. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Main entry under title: Chromosome numbers in Compositae, XII. -

Plant Life MagillS Encyclopedia of Science

MAGILLS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF SCIENCE PLANT LIFE MAGILLS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF SCIENCE PLANT LIFE Volume 4 Sustainable Forestry–Zygomycetes Indexes Editor Bryan D. Ness, Ph.D. Pacific Union College, Department of Biology Project Editor Christina J. Moose Salem Press, Inc. Pasadena, California Hackensack, New Jersey Editor in Chief: Dawn P. Dawson Managing Editor: Christina J. Moose Photograph Editor: Philip Bader Manuscript Editor: Elizabeth Ferry Slocum Production Editor: Joyce I. Buchea Assistant Editor: Andrea E. Miller Page Design and Graphics: James Hutson Research Supervisor: Jeffry Jensen Layout: William Zimmerman Acquisitions Editor: Mark Rehn Illustrator: Kimberly L. Dawson Kurnizki Copyright © 2003, by Salem Press, Inc. All rights in this book are reserved. No part of this work may be used or reproduced in any manner what- soever or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy,recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the copyright owner except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information address the publisher, Salem Press, Inc., P.O. Box 50062, Pasadena, California 91115. Some of the updated and revised essays in this work originally appeared in Magill’s Survey of Science: Life Science (1991), Magill’s Survey of Science: Life Science, Supplement (1998), Natural Resources (1998), Encyclopedia of Genetics (1999), Encyclopedia of Environmental Issues (2000), World Geography (2001), and Earth Science (2001). ∞ The paper used in these volumes conforms to the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48-1992 (R1997). Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Magill’s encyclopedia of science : plant life / edited by Bryan D. -

University of Florida's

variety information University of Florida’s For more information on the varieties discussed in this article, direct your inquiries Best to the following companies. AMERICAN TAKII INC. (831) 443-4901 www.takii.com The best of times, the worst of times and things ERNST BENARY OF AMERICA to come for seed-propagated bedding plants. (815) 895-6705 www.benary.com By Rick Kelly, Rick Schoellhorn, FLORANOVA PLANT BREEDERS Zhanao Deng and Brent K. Harbaugh (574) 674-4200 www.floranova.co.uk GOLDSMITH SEEDS rowers around the sive replicated trials. Cultivars to be cultivar to compare new entries in (800) 549-0158 country face a deci- evaluated are placed into classes by each new trial. If the new entry per- www.goldsmithseeds.com sion when producing species, flower and foliage color, forms better, it takes the best-of- bedding plants for plant height and growth habit. Two class position; if only one plant is KIEFT SEEDS HOLLAND (360) 445-2031 the Deep South and similar cli- duplicate fields are planted. One entered in a class, it becomes the www.kieftseeds.com mates around the world. There, field is scouted and sprayed, as uncontested best-of-class. We coop- needed. Plant measurements, per- erate with four of Florida’s premier flowers may flourish year-round; PANAMERICAN SEED however,G the moderate to high tem- formance, flowering data and culti- public gardens to display the best- (630) 231-1400 peratures and ample moisture fuel var performance are evaluated of-class selections in their formal www.panamseed.com the fires of disaster, as plant pests there. -

Sierra Azul Wildflower Guide

WILDFLOWER SURVEY 100 most common species 1 2/25/2020 COMMON WILDFLOWER GUIDE 2019 This common wildflower guide is for use during the annual wildflower survey at Sierra Azul Preserve. Featured are the 100 most common species seen during the wildflower surveys and only includes flowering species. Commonness is based on previous surveys during April for species seen every year and at most areas around Sierra Azul OSP. The guide is a simple color photograph guide with two selected features showcasing the species—usually flower and whole plant or leaf. The plants in this guide are listed by Color. Information provided includes the Latin name, common name, family, and Habit, CNPS Inventory of Rare and Endangered Plants rank or CAL-IPC invasive species rating. Latin names are current with the Jepson Manual: Vascular Plants of California, 2012. This guide was compiled by Cleopatra Tuday for Midpen. Images are used under creative commons licenses or used with permission from the photographer. All image rights belong to respective owners. Taking Good Photos for ID: How to use this guide: Take pictures of: Flower top and side; Leaves top and bottom; Stem or branches; Whole plant. llama squash Cucurbitus llamadensis LLAMADACEAE Latin name 4.2 Shrub Common name CNPS rare plant rank or native status Family name Typical bisexual flower stigma pistil style stamen anther Leaf placement filament petal (corolla) sepal (calyx) alternate opposite whorled pedicel receptacle Monocots radial symmetry Parts in 3’s, parallel veins Typical composite flower of the Liliy, orchid, iris, grass Asteraceae (sunflower) family 3 ray flowers disk flowers Dicots Parts in 4’s or 5’s, lattice veins 4 Sunflowers, primrose, pea, mustard, mint, violets phyllaries bilateral symmetry peduncle © 2017 Cleopatra Tuday 2 2/25/2020 BLUE/PURPLE ©2013 Jeb Bjerke ©2013 Keir Morse ©2014 Philip Bouchard ©2010 Scott Loarie Jim brush Ceanothus oliganthus Blue blossom Ceanothus thyrsiflorus RHAMNACEAE Shrub RHAMNACEAE Shrub ©2003 Barry Breckling © 2009 Keir Morse Many-stemmed gilia Gilia achilleifolia ssp. -

Plants for Bats

Suggested Native Plants for Bats Nectar Plants for attracting moths:These plants are just suggestions based onfloral traits (flower color, shape, or fragrance) for attracting moths and have not been empirically tested. All information comes from The Lady Bird Johnson's Wildflower Center's plant database. Plant names with * denote species that may be especially high value for bats (based on my opinion). Availability denotes how common a species can be found within nurseries and includes 'common' (found in most nurseries, such as Rainbow Gardens), 'specialized' (only available through nurseries such as Medina Nursery, Natives of Texas, SA Botanical Gardens, or The Nectar Bar), and 'rare' (rarely for sale but can be collected from wild seeds or cuttings). All are native to TX, most are native to Bexar. Common Name Scientific Name Family Light Leaves Water Availability Notes Trees: Sabal palm * Sabal mexicana Arecaceae Sun Evergreen Moderate Common Dead fronds for yellow bats Yaupon holly Ilex vomitoria Aquifoliaceae Any Evergreen Any Common Possumhaw is equally great Desert false willow Chilopsis linearis Bignoniaceae Sun Deciduous Low Common Avoid over-watering Mexican olive Cordia boissieri Boraginaceae Sun/Part Evergreen Low Common Protect from deer Anacua, sandpaper tree * Ehretia anacua Boraginaceae Sun Evergreen Low Common Tough evergreen tree Rusty blackhaw * Viburnum rufidulum Caprifoliaceae Partial Deciduous Low Specialized Protect from deer Anacacho orchid Bauhinia lunarioides Fabaceae Partial Evergreen Low Common South Texas species -

Ground Covers for Arizona Landscapes

Cooperative Extension Ground Covers for Arizona Landscapes ELIZABETH DAVISON Lecturer Department of Plant Sciences AZ1110 April 1999 Contents Why Use a Ground Cover? .......................................................................................................... 3 Caveats .......................................................................................................................................... 3 How to Select a Ground Cover ................................................................................................... 3 General Planting Instructions ...................................................................................................... 4 Care of Established Plantings....................................................................................................... 4 Water ............................................................................................................................................. 5 Exposure ........................................................................................................................................ 5 Plant Climate (Hardiness) Zones ................................................................................................ 5 Plant Climate Zone Map .............................................................................................................. 6 Plant List ........................................................................................................................................ 7 Plant Name Cross Reference -

Protocol Information

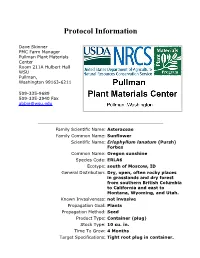

Protocol Information Dave Skinner PMC Farm Manager Pullman Plant Materials Center Room 211A Hulbert Hall WSU Pullman, Washington 99163-6211 509-335-9689 509-335-2940 Fax [email protected] Family Scientific Name: Asteraceae Family Common Name: Sunflower Scientific Name: Eriophyllum lanatum (Pursh) Forbes Common Name: Oregon sunshine Species Code: ERLA6 Ecotype: south of Moscow, ID General Distribution: Dry, open, often rocky places in grasslands and dry forest from southern British Columbia to California and east to Montana, Wyoming, and Utah. Known Invasiveness: not invasive Propagation Goal: Plants Propagation Method: Seed Product Type: Container (plug) Stock Type: 10 cu. in. Time To Grow: 4 Months Target Specifications: Tight root plug in container. Propagule Collection: Fruit is an achene which ripens in mid to late July. Seed is dark grayish brown to nearly black in color. The pappus is reduced to short scales or is lacking entirely and the achene is not windborne. Seed will hold in the inflorescence longer than the seed of many other members of Asteraceae, but will shatter within a week or so of ripening. Small amounts are collected by hand and stored in paper bags or envelopes at room temperature until cleaned. 818,000 seeds/lb (Hassell et al 1996). Propagule Processing: Small amounts are rubbed to free the seed, then cleaned with an air column separator. Larger amounts can probably be threshed with a hammermill, then cleaned with air screen equipment. Clean seed is stored in controlled conditions at 40 degrees Fahrenheit and 40% relative humidity. Pre-Planting Treatments: Seed stored at room temperature remains viable after 8 years (Mooring 1975) but germination decreases sharply after 2 years (Mooring 2001).