The Unusual Silence Event Programme

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Is She Dead Yet? Rehearsing La Bohéme at Opera Australia

Is she dead yet? Rehearsing La Bohéme at Opera Australia Avi Michael Casebook submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Bachelor of Arts (Honours). Department of Performance Studies University of Sydney 2009 Many thanks to my supervisors, Dr. Ian Maxwell and Dr. Amanda Card. 2 | Is she dead yet? Table of Contents Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. 4 Causality: My Method of Operating ...................................................................................................... 7 Context .............................................................................................................................................. 12 The Project ................................................................................................................................................. 12 My Musical Inertia ................................................................................................................................... 14 A Rehearsal Space in Surry Hills ......................................................................................................... 15 Personnel ................................................................................................................................................... -

Roger Kirk Cv

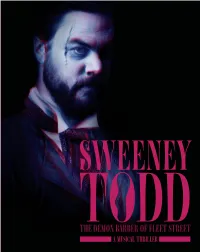

Roger Kirk - Page 1 of 10 ROGER KIRK SET AND COSTUME DESIGNER THEATRE 2015 BROADWAY TO OZ: HUGH Costume Design. Dainty Group JACKMAN LIVE IN CONCERT 2015 SWEENEY TODD Costume Design. Victorian Opera 2014 MIRACLE CITY Costume Design. Luckiest Productions 2012 KING KONG THE MUSICAL Costume Design. Global Creatures. 2011 NUTCRACKER MAGIC Costume Design. Shanghai City Entertainment Group. 2011 TALES OF HOFFMAN Set & Costume Design. West Australian Opera. 2010 THE SILVER ROSE Set & Costume Design. The Australian Ballet. 2009- MANON LESCAUT Set & Costume Design. Opera Australia 2010 2009- A LITTLE NIGHT MUSIC Set & Costume Design. Opera Australia 2010 2009 AIDA Set & Costume Design. Opera Australia. 2007 – MY FAIR LADY Costume Design. Opera Australia 2008 Opera Australia at the Theatre Royal/ National Tour. 2007 42nd STREET Costume Design. China Tour Troika Entertainment 2007 THE PIRATES OF PENZANCE Costume Design. Opera Australia. 2006 LE CORSAIRE Set and Costume Design. Shanahan Management Pty Ltd Level 3 Berman House 91 Campbell Street Surry Hills NSW 2010 PO Box 1509 Darlinghurst NSW 1300 Australia ABN 46 001 117 728 Telephone 61 2 8202 1800 Facsimile 61 2 8202 1801 [email protected] Roger Kirk - Page 2 of 10 Bayerische Staatsballett - Munich 2006 DUSTY, THE ORIGINAL POP DIVA Set and Costume Design DUSTY Productions Dir. Stuart Maunder 2005 THE SILVER ROSE Set and Costume Design. Bayerische Staatsballett - Munich Dir. Graeme Murphy 2005 H.M.S PINAFORE Set and Costume Design Opera Australia 2003 THE KING & I Set and Costume Designer. Stratford Festival of Canada. Dir. Susan H. Schulman. 2001 THE WIZARD OF OZ Set and Costume Designer. -

2007 2008 2007 Note $000 $000 Note $000 $000

PERFORMING FOR TODAY BUILDING FOR FUTURE GENERATIONS SYDNEY OPERA HOUSE TRUST ANNUAL REPORT 2007/08 PERFORMING FOR TODAY Symphonie Fantastique Le Grand Cirque Sydney Opera House is one of the busiest and most successful performing arts centres in the world. FOR TODAY Operating 363 days, 1,269,996 people attended 1,661 performances over the year. Performance Partnerships 53,726 children attended our Kids at the Through our own programming division, Resident companies – The Australian House and House:Ed programs designed Sydney Opera House Presents, our resident Ballet, Opera Australia, Sydney Symphony for young audiences. companies and major hirers we generated and Sydney Theatre Company – were 2,709 people attended the Balnaves Open a wealth of diverse performances including responsible for 54% of our total audiences House Program that extends access to the international artists and ensembles, local and and 34% of all performances. broader community by offering $5 tickets. newly commissioned works, emerging artists Our Major Partners NAB and HP, our and programs for families and schools. Approximately 120,000 unique visitors five Media Partners and our 20 Corporate visit our website every month. Sydney Opera House Presents aims to complement Sponsors help us to achieve our business the programming of our resident companies objectives. 605 people are employed at Sydney Opera and extend the cultural experiences available House and help us to achieve success every day. Our 417 private donors generously contributed to the people of Sydney and NSW. Our They are joined by many, many other people $545,305, an increase of 15% year on programming under this banner represented on site who work with our resident companies, year, to allow us to invest in the world’s best 44% of all performances across our venues. -

THE MIKADO Gilbert & Sullivan

THE MIKADO Gilbert & Sullivan FESTIVAL THEATRE STATE OPERA SOUTH AUSTRALIA THE MIKADO A Comedic Opera in two acts Gilbert & Sullivan by Gilbert & Sullivan Orchestration by Eric Wetherell A Comedic Opera in two acts Orchestration by Eric Wetherell CREATIVES CAST Conductor - Simon Kenway Mikado - Pelham Andrews Director - Stuart Maunder Nanki Poo- Dominic J. Walsh Design - Simone Romaniuk Ko-Ko - Byron Coll Lighting Designer - Donn Byrnes Pooh-Bah - Andrew Collis Choreography - Siobhan Ginty Pish-Tush - Nicholas Cannon Associate Choreographer - Penny Martin Yum-Yum - Amelia Berry Repetiteur - Andrew George Pitti-Sing - Bethany Hill Peep-Bo - Charlotte Kelso Katisha - Elizabeth Campbell 9-23 NOVEMBER ADELAIDE FESTIVAL THEATRE STATE OPERA CHORUS The Mikado is an original ADELAIDE SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA production by Opera Queensland. Director’s Note There is no theatrical phenomenon in the Antipodes The G&S operetta’s durability is extraordinary but with the staying power of Gilbert and Sullivan. not unexplainable. After all, Gilbert’s dramatic situations are still funny, and Sullivan’s music Our love affair with G&S (and let’s face it, how succeeds in providing a kind of romantic foil to many creators are instantly recognised by their Gilbert’s pervasive drollery and cynicism. This kind initials alone?) is almost as enduring as the works of friction was very much at the heart of Gilbert themselves. In the 1870s, when policing copyright and Sullivan’s creative relationship and the gentle was much trickier than it is now, two rival “pirate” satire alternating with genuine heartfelt emotion is productions of H.M.S. Pinafore were playing across a combination that never ages – indeed, perhaps it’s the street from one another in Melbourne. -

Tosca Nixon in China a Midsummer Night's Dream

TOSCA NIXON IN CHINA A MIDSUMMER NIGHT’S 19 DREAM THE GONDOLIERS BREAKING THE WAVES ZANETTO SUSANNA’S SECRET IRIS 20CAVALLERIA RUSTICANA ZINGARI UTOPIA, LIMITED FOX-TOT! MERRILY WE ROLL ALONG 5 Subscription Information 6 Tosca 8 Nixon in China 10 A Midsummer Night’s Dream 12 The Gondoliers 14 Breaking the Waves 16 Opera in Concert 20 Opera Highlights 22 Fox-tot! 24 Merrily We Roll Along 26 Amadeus & The Bard 28 Pop-up Opera 32 Emerging Artists 33 Opera Unwrapped 34 Dementia Friendly Performances 36 Audio-described Performances 37 Pre-show Talks 38 Get Involved 40 Box Office Information A huge thank you to all our business sponsors and corporate members: Thanks also to our corporate supporters: Accenture, Caledonian MacBrayne, Cameron, Eusebi Deli, Glasgow Chamber of Commerce, Glasgow Memory Clinic, M.A.C., NorthLink Ferries and Pentland Ferries. WELCOME TO SCOTTISH OPERA’S 2019|20 SEASON Scottish Opera has been entertaining At a time when, perhaps more than ever, audiences the length and breadth of the we are all thinking and talking about country for over 56 years, and still at the heart partnership, we are proud of the relationships of all we do are the words of our founder, that are critical both to Scottish Opera’s success Sir Alexander Gibson, whose vision was and to our ability to create new work for you. ‘to lay the treasures of opera at the feet We don’t work in isolation, and this Season of the people of Scotland’. exemplifies this spirit of collaboration across the world of opera, embracing our partnerships In our 2019/20 Season, we are delighted and co-productions with festivals, companies to take forward his momentous legacy and opera houses in Scotland, England, with a wealth of operatic fare – including Australia, Denmark, Spain and the United 12 operas – that takes us to over 50 venues, States, and with artists and creative teams and is augmented by numerous events in from near and far. -

What the Fandango?! Company Biographies. TOURING

What the Fandango?! Company Biographies. TOURING: Robert Hofmann, performer and creator. Robert has sung many roles with the West Australian Opera including Koko in The Mikado, Dulcamara in The Elixir of Love, Falke in Die Fledermaus, Hobson in Peter Grimes as well as concert performances in regional Western Australia. He performed with the WA Opera in Education program from 2010 to 2015 at schools in Perth metro area as well as several regional schools tours. Robert burst onto the cabaret scene with Desperately Young at Heart winning the Cabaret Award (WA) at Perth Fringe World 2014 in its world-premiere season which later performed at Edinburgh Fringe, Downstairs at the Maj and Beverly (regional WA.) Robert’s new cabaret, What the Fandango?! received several 5 star reviews at Perth Fringe World 2018 and 2019 and was critically acclaimed in two performances in New York City in June 2019. Robert regularly performs with Perth’s Freeze Frame Opera. Since 2011 Robert has performed with comic soprano duo DivaLicious in Perth, WA Regions, Adelaide Fringe and Sydney Opera House. Robert is also an experienced concert soloist and has performed often with the St Georges Cathedral Choir under the direction of Joseph Nolan. Cathie Travers, music director and piano accordionist. Playing the piano accordion is the brilliant Cathie Travers whose evocative playing inspired the South American theme of What the Fandango?! Cathie is one of the finest accordionists in Australia and has collaborated with many artists including Meow Meow, the Australian Chamber Orchestra and Barry Humphries. Her performance and creative work has appeared in all the major cities of Australia – and internationally in Canada, the USA, the UK, Malaysia, & Japan. -

Read the Programme

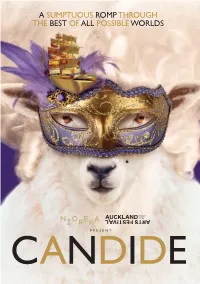

A SUMPTUOUS ROMP THROUGH THE BEST OF ALL POSSIBLE WORLDS COVER PRESENT CANDIDE Welcome Leonard Bernstein’s Candide famously opened on Broadway in 1956 and closed after some 73 performances. It could have easily slipped into the long list of forgotten musicals save for the fact that it spawned one of the most loved Broadway Original cast albums of all time, the fi rst track being ‘that’ overture. The show fi nally became a hit on Broadway in the 1974 Harold Prince production, winning a special Tony Award for outstanding contribution to the artistic development of the musical theatre. Termed a revival, this was almost a completely new show; the book had been totally rewritten, the orchestral forces reduced, much of the music was cut and the Auckland Town Hall voices, Broadway music theatre. 23 & 24 March at 7.30pm And even though he was grateful 25 March at 5pm Candide had fi nally found an Music by Leonard Bernstein, book by Hugh audience, the composer missed Wheeler after Voltaire, Lyrics by Richard the rest of his show: the music, Wilbur, with additional lyrics by Stephen the orchestrations and the Sondheim, John La Touche, Lillian Hellman, Dorothy Parker and Leonard Bernstein voices. Orchestrations by Leonard Bernstein and Hershy Kay; Musical continuity and additional Tonight, some sixty years after orchestrations by John Mauceri. Licensed by Hal Leonard Australia, exclusive agent for the original production, and Boosey & Hawkes Music Publishers Ltd. after many, many versions, you’ll hear the Candide that Please note: Information is correct at the time of printing. New Zealand Opera reserves the right to make alterations Bernstein authorised, the to the cast as required due to unavoidable circumstances. -

Scottish Opera Announces 2019/20 Season

PRESS RELEASE 10 April 2019 ** EMBARGOED UNTIL 00:00:01, 10 April 2019** SCOTTISH OPERA ANNOUNCES 2019/20 SEASON • European premiere of Missy Mazzoli’s Breaking the Waves at Edinburgh International Festival, directed by Tom Morris • Anthony Besch’s much-loved production of Puccini’s Tosca opens main season • Scottish Opera premiere of John Adams’ Nixon in China, conducted by Joana Carneiro and directed by John Fulljames • Dominic Hill, Artistic Director of Citizens Theatre, directs new production of Britten’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream • Stuart Maunder directs a new production of Gilbert & Sullivan’s The Gondoliers • World premiere of Fox-tot!, a new opera for toddlers by former Scottish Opera Composer in Residence, Lliam Paterson, directed by Roxana Haines • Scottish Opera returns to Lammermuir Festival with a double bill • Opera in Concert performances continue celebrations of Mascagni and Gilbert & Sullivan • Amadeus & The Bard explores the links between Mozart and Robert Burns • Opera Highlights visits 34 venues around Scotland in Autumn 2019 and Spring 2020 Scottish Opera has unveiled its 2019/20 Season which includes a European premiere at the Edinburgh International Festival, three further new productions, one revival, six titles in the 1 Opera in Concert series, and the world premiere of a new ‘opera for toddlers’ at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe. A truly international line-up of singers appears throughout the Season. Making their debuts with the Company are Trevor Eliot Bowes, Orla Boylan, Wallis Giunta, Eric Greene, Byron Jackson -

Tosca-Programme-2015.Pdf

An opera in three acts by Giacomo Puccini. Libretto by Giuseppe Giacosa and Luigi Illica after the play La Tosca by Victorien Sardou. Tosca was first performed on 14 January 1900 at Teatro Constanzi in Rome. The Puccini ― 1900 performance lasts approximately 2 hours and 15 minutes, including an interval of 20 minutes. Sung in Italian with English surtitles. A New Zealand Opera production. AUCKLAND ASB Theatre, Aotea Centre 17, 19, 23, 25 September 2015, 7.30pm 27 September, 2.30pm Accompanied by the Auckland Philharmonia Orchestra WELLINGTON St James Theatre 10, 15, 17 October 2015, 7.30pm 13 October, 6pm Accompanied by the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra 2015 season P.3 Welcome Welcome to New Zealand Opera’s second Auckland and Wellington offering for the year … Puccini’s monumentalTosca . Whose spine doesn’t tingle to the opening chords of this glorious melodrama? The great Russian composer Shostakovich said of Puccini: “He wrote marvellous operas but dreadful music”. Lucky for us Puccini never pretended to do anything else. Towards the end of his life he said God had touched him with His little finger and said “Write only for the theatre” and so he did. Puccini has been responsible for more real, and yet theatrical ‘heart on the sleeve’ emotion than any other operatic composer. And his Tosca is the opera that conquered the world. This passionate story of lust, revenge and sacrifice has become one of the most loved operas in the repertoire. Tosca is the fire that burns throughout this musical thriller. She is the ultimate Diva. To bring this lady to life we are thrilled to welcome Orla Boylan, who stunned audiences in our 2013 season of The Flying Dutchman. -

Sweeney Todd in the Antipodes Humanity (‘The Lives of the the Judge Who Sentenced Him

BEN MINGAY & ANTOINETTE HALLORAN, WA OPERA (PHOTO: JAMES ROGERS) Dear Opera Lover You play an important part in driving this large arts employment goal. Your attendance, your donations, You are so much more than a lover of opera! Please your advocacy and your willingness to share in our know how treasured you are because of your appetite success has a multiplying efect. Thank you. As we for music, your passion for drama, and your support begin our Annual Appeal for 2021 I hope you will of our artists, musicians, and indeed our Company as consider deepening the value of your attendance here a whole. Opera is a broad church, both in content and at Sweeney Todd with a donation to State Opera. I the unique personalities it attracts, and I hope you hope it is plainly evident that we funnel as much of will feel utterly complimented when I tell you that you our income as we can directly into productions and are in the very best company here this evening. performances; that is where your financial support will make every bit of diference. Donating is easy: I wish you had a chance to peek backstage and into stateopera.com.au/donate the rehearsal rooms over these last few busy months. I know Stuart will agree with me when I say it has been My special thanks to those who have already food for the soul to see such a hive of activity taking donated, sponsored and contributed in so many place, and I personally have been deeply gratified and ways. -

Leoš Janácek

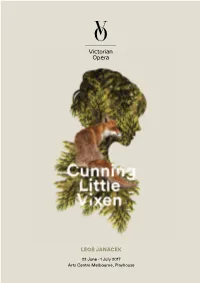

LEOŠ JANÁCEK 22 June - 1 July 2017 Arts Centre Melbourne, Playhouse Welcome Welcome to our production of Cunning Each year, Victorian Opera continues to Little Vixen. build its reputation for breaking boundaries and exciting collaborations. This work is from Janácek’s final The second half of our 2017 season years. He wrote it in 1924, preceding continues in this spirit, with productions The Makropulos Affair (1926) and his including our co-production with final work From the House of the Dead Malthouse Theatre of Tom Waits’ (1927). Janácek’s late style is unique, Black Rider, Copland’s Youth Opera an unlikely synthesis of Moravian folk The Second Hurricane as well as the elements, rhythmic complexity and world premiere of Gordon Kerry’s opera fluidity, hypnotic repetition and an The Snow Queen for Wodonga. individual take on the harmonic heritage of the 19th and early 20th century: From the entire Victorian Opera family, it’s spiky, sometimes unfriendly to thank you for joining us at the theatre for performers, but its gestures stay in the Cunning Little Vixen; a profound memory – they are like nothing else in meditation on youth, growing old and the operatic canon. the inexorable march of time – delivered without a trace of sentimentality but To guide this work, we extend the warmest with humour, pathos and great welcome to both Stuart Maunder AM life-affirming strength of mind. and Roger Kirk AM, both long standing members of VO’s extended family. It is a RICHARD MILLS AM particular pleasure to introduce the young Artistic Director, and very talented Jack Symonds, Artistic Victorian Opera Director of Sydney Chamber Opera, with whom we are collaborating on a number of projects. -

Sydney Opera Hou S E 2010/11 IMAGINATION LIVES INSIDE

SYDNEY OPERA HOU S E 2010/11 E 2010/11 ANNUAL REPORT IMAGINATION LIVES INSIDE IMAGINATION LIVES INSIDE IMAGINATION SYDNEY OPERA HOUSE 2010/11 VIVID LIVE 2011 WAS A TRUE SPECTACLE OF CREATIVE GENIUS WITHIN SYDNEY OPERA HOUSE AND BEYOND. COURAGEOUS THOUGHTS, IDEAS AND EXPERIENCES CAME TOGETHER TO INSPIRE IMAGINATION AND CREATE A RELEVANT AND VITAL PART OF THE AUSTRALIAN CULTURAL LANDSCAPE. 'IMAGINATION LIVES INSIDE' PROMOTES INNOVATION THROUGH VIVID COLOUR THEORY AND A UNIQUE HIDE AND REVEAL EXPLORATION, WHICH EXPRESSES NOT ONLY THE SYDNEY OPERA HOUSE BRAND, BUT ALSO THE STRENGTH OF AN IDEA. Sydney Opera House Presents Martha Wainwright 3 ANNUAL REPORT 2010/11 IMAGINATION LIVES INSIDE IMAGINATION TABLE OF CONTENTS The Hon. George Souris MP MiniSTer for THe ArTS We have the pleasure of presenting the Annual Report of the Sydney Opera House for the year ended 30 June 2011, for presentation to Parliament. This report has been prepared in accordance with the provisions of the Annual Reports (Statutory Bodies) Act 1984 and the Public Audit and Finance Act 1983. KiM WilliAMS AM CHAirMAn riCHArd evAnS CHief exeCuTive 3 Letter to Minister 54 Earning Our Way 4 Highlights 58 Governance 6 Chairman’s Message 64 People and Culture 8 CEO’s Message 66 Financial Overview 10 Vision and Goals 70 Financial Statements 12 Outcomes and Objectives 96 Government Reporting 16 Artistic Excellence 116 Performance List 20 Sydney Opera House Presents 120 Donors Acknowledgement 26 Resident and Supported Companies 122 Contact Information 32 Community Engagement and Access 123 Site Map 36 Community Outreach and Participation 124 Index 38 Beyond Bennelong 125 Sponsors 40 Customer Service and Access 42 A Vibrant and Sustainable Site 46 Our Precinct 48 Building and Maintenance 50 Environmental Sustainability 52 Safety and Security 4 SYDNEY OPERA HOUSE IMAGINATION LIVES INSIDE IMAGINATION HIGHLIGHTS 2010/11 A TTENDANCE AT PERFORMANCES HAS INCREASED BY 20% OVER THE LAST 10 YEARS.